Last updated: May 7, 2024

Person

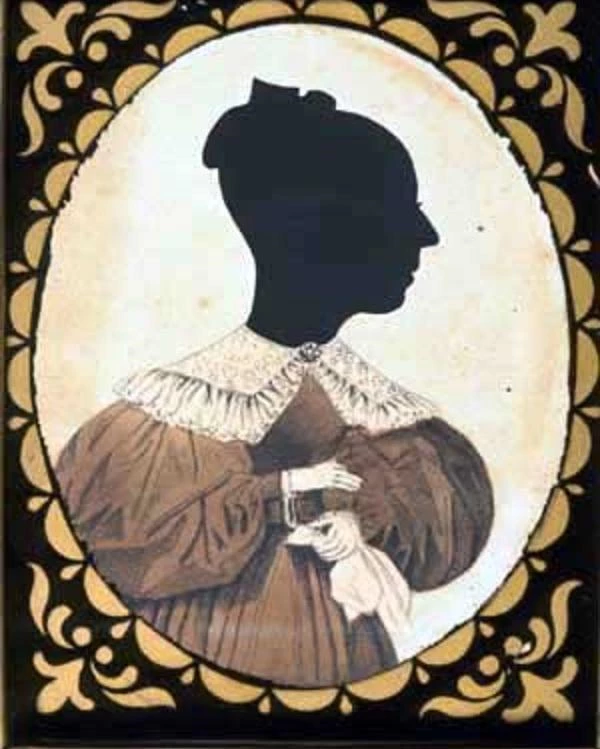

Sarah Bagley

Lowell NHP Collection

“Let no one suppose the ‘factory girls’ are without guardian. We are placed in the care of overseers who feel under moral obligation to look after our interests.”

-Sarah Bagley, 1840

Lowell Offering

“I am sick at heart when I look into the social world and see woman so willingly made a dupe to the beastly selfishness of man.”

-Sarah Bagley, 1847

Letter to Angelique Martin

Between 1837 and 1848, Sarah Bagley’s view of the world around her changed radically. While much of her life remains surrounded by questions, the record of Bagley’s experiences as a worker and activist in Lowell, Massachusetts reveals a remarkable spirit. Condemned by some as a rabble rouser and enemy of social order, many have celebrated her as a woman who fought against the confines of patriarchal industrial society on behalf of all her sisters in work and struggle.

Lowell Mill Girl

Sarah George Bagley was born April 19, 1806 to Nathan and Rhoda Witham Bagley. Raised in rural Candia, New Hampshire, she came to the booming industrial city of Lowell in 1837 at the age of 31, where she began work as a weaver at the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. Though older than many of the Yankee women who flocked to Lowell’s mills, Bagley shared with them the shift from rural family life to the urban industrial sphere.

While many found a sense of independence in coming to the city and earning a wage for the first time, the presence of paternalistic capitalism ensured that working women would never be “without guardian;” or as Bagley would later assert, that factory women would never experience true freedom. Bagley was initially inclined to accept the prescribed order in the Spindle City—she became an excellent weaver and began to write for the Lowell Offering, a literary magazine written by mill workers but overseen and partly funded by the mill corporations. Bagley’s 1840 essay entitled “The Pleasures of Factory Work,” which argued that cotton mill labor was congenial to “pleasurable contemplation” and other noble pursuits, was representative of the positive, proper image of the mills presented in the pages of the Offering.

Stirrings of Conflict

Was it deteriorating conditions in the cotton factories or some internal shift in Sarah Bagley’s worldview that precipitated her transformation from “mill girl” to ground-breaking labor activist in the span of only a few short years? By 1840 the exploitation of Lowell mill workers was becoming increasingly apparent: the frequent speedups and constant pressure to produce more cloth drove Bagley from the weave room into the cleaner, more relenting dressing room. Here she oversaw the starching (or “dressing”) of the warp threads that constitute the framework for woven cloth.

By 1842 the pressures that Bagley had experienced as a weaver began to erupt in the form of labor conflict. In that year the Middlesex Manufacturing Company, one of Lowell’s textile giants, announced a speedup and subsequent 20% pay cut. In protest, seventy female workers walked out. All were fired and blacklisted. Lowell’s industrial capitalists made it very clear that they would not tolerate challenges to their authority, especially not by young female workers.

The walkout of 1842 did not instantly convert Sarah Bagley into a labor activist; several months after the unsuccessful strike by the Middlesex weavers, Bagley returned to weaving, this time as an employee of the Middlesex mills.

Radical Reformer

A radical change in Sarah’s own views of the world around her, however, was not far off. How exactly she became involved with the labor movement is uncertain. In 1844, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was founded, becoming one of the earliest successful organizations of working women in the United States, with Sarah Bagley as its president. Working in cooperation with the New England Workingmen’s Association (NEWA) and spurred by a recent extension of work hours, the organizations submitted petitions totaling 2,139 names to the Massachusetts state legislature in 1845. These petitions demanded the reduction of the workday to ten hours on behalf workers’ health as well as their “intellectual, moral and religious habits.” In response, the legislature called a hearing and asked Bagley, among eight others, to testify. Despite the efforts of Bagley and her colleagues, the legislators ultimately refused to act against the powerful mills.

While advocating for the ten hour workday and against corporate abuses remained the cornerstones of the LFLRA’s activism under Bagley’s presidency, women’s rights issues quickly assumed a prominent role as well. Speaking at the first New England Workingmen’s Association convention at a time when public speaking represented a radical departure from acceptable feminine behavior, Bagley called on male workers to exercise their right to vote on behalf of female workers who lacked political representation.

The year 1845 also saw Sarah taking on new responsibilities as a writer and editor for the Voice of Industry, founded in 1844 by the New England Workingmen’s Association. In a July Fourth speech, Bagley—just named one of the NEWA’s five new vice presidents—condemned the Lowell Offering and its editor Harriet Farley as “a mouthpiece of the corporations,” voicing a deep transformation of her own views. The ensuing public feud belied Bagley’s own praise of the mill companies published in the Offering only five years prior.

1846 was a busy year for Bagley and the Female Labor Reform Association, as she and several associates traveled throughout New England recruiting workers and organizing chapters of the FLRA and the NEWA. She also served as a delegate to numerous labor conventions and associated with a wide variety of progressives beyond the immediate labor movement, from abolitionists to prison reformers. Having left mill work in early 1846, Bagley now considered labor reform her primary calling. 1846 also saw an increase in the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association’s activities, mounting a campaign against yet another speedup and piece rate reduction, establishing a lecture series for workers, and penning pamphlets exposing the contradictions of mill owner paternalism and decrying the “ignorance, misery, and premature decay of both body and intellect” caused by mill work.

These achievements, however, were tempered by continued frustration on the ten-hour front. A second petition, this time numbering 4,500 signatures, was submitted to the legislature and rejected. Perhaps in part owing to the lack of success in attaining this goal, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association began to shift its focus away from the militant labor activism espoused by Sarah Bagley. Around this time Bagley also came into conflict with the Voice of Industry’s new editor, John Allen, over the role of women in the newspaper’s production. In October of 1846 Bagley published her last piece in the Voice of Industry; in early 1847 she left the Female Labor Reform and Mutual Aid Society (formerly LFLRA) after three brief but influential years of radical activism.

"Can A Woman Keep A Secret?"

In 1846 Sarah Bagley once again defied expectations when she took a job as the nation’s first female telegraph operator. Over the course of two years, Bagley was put in charge of telegraph operations in Lowell and then Springfield, MA. In 1848, Bagley briefly returned to factory work at the Hamilton Mill in Lowell. She was employed in the weave room for five months. During this period, Bagley struggled with financial strain and ongoing conflicts with local activists. She told a friend: “I feel as though my labors for the public good are nearly ended. It takes time and that is my only means. It takes money that I can ill afford.” In the fall of 1848, Bagley left Lowell, and likely never returned.

The second half of this remarkable leader’s life has received far less attention, though sparse public records, letters, and newspaper clippings fill in some gaps. Upon leaving Lowell, Bagley briefly taught women how to cut dresses with the Rosine Association in Philadelphia. She seems to have also been introduced to homeopathic medicine during this time. Then Sarah G. Bagley disappears from the historical record. In her place is Mrs. James Durno, a woman listed on many records as “keeping house.” In November 1850, Sarah married James Durno, a homeopathic doctor who sold medicines. She also practiced as a rheumatic physician (while a married woman) for several years in Albany. In the 1850s, the Durnos moved to Brooklyn and launched a company that made snuff for catarrh, a kind of cold remedy. After her husband’s passing, Sarah traveled and ultimately returned to Philadelphia, where she passed away in 1889. She is buried in the Laurel Hill Cemetery with family.

A Legacy of Change

Sarah Bagley worked as a weaver, writer, editor, public speaker, and telegraph operator in Lowell. She turned threads into cloth, words into stories, and electrical pulses into messages. The season of her life that she spent in the Merrimack Valley was not very long, adding up to just 11 of her 83 years. As a younger woman, Sarah Bagley worked hard to support herself, her extended family, and especially her ill father. As an older woman, Sarah Durno entered the medical field and sustained her own family business. All her life, she worked; and through that work, she tended to what ailed people. The fight for worker's rights that Bagley championed while in Lowell continues throughout the world today.

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 1 second

Sarah Bagley became a weaver in Lowell in 1837. Within a few years, Bagley began protesting unfair labor practices and worked with other women to form the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. Testifying before the state legislature in 1845, Bagley advocated for a shorter work day. As editor of the newspaper Voice of Industry, Bagley promoted women’s and workers’ rights. Bagley later became the nation’s first female telegraph operator. What is a cause that you care about?