Last updated: January 29, 2026

Person

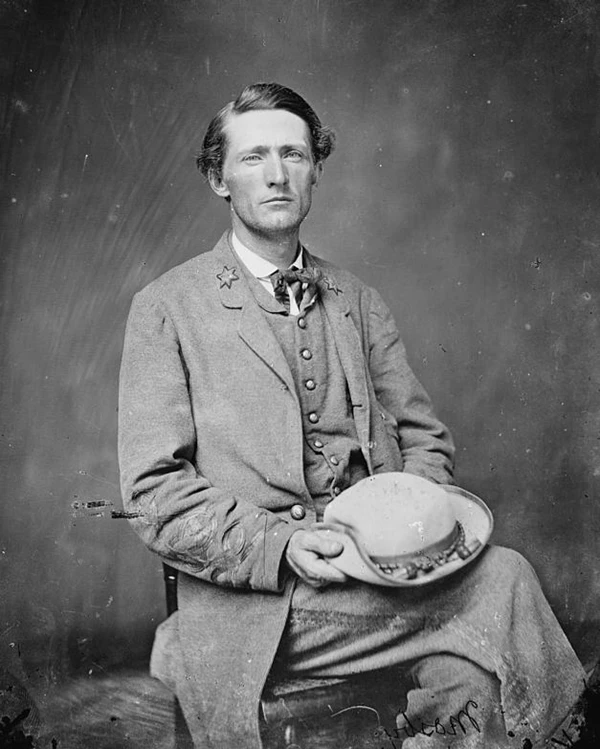

John Singleton Mosby

Library of Congress

John Singleton Mosby was a lawyer turned Confederate cavalry raider. His "rangers" raided US supply lines in Northern Virginia. The area earned the nickname "Mosby's Confederacy." After the war Mosby joined the Republican Party and befriended his former enemy Ulysses S. Grant. Mosby maintained that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War. Infuriated former Confederate southerners saw him as a traitor.

Youthful Lawyer

At 19 years old, Mosby was expelled from the University of Virginia and jailed after shooting a classmate. He was pardoned in 1853. Afterwards, Mosby studied law and established his own practice. In 1857 he married Pauline Clark and moved to Southwestern Virginia near the Cumberland Gap.

Moral Dilemma

Mosby initially spoke out against secession and was opposed to slavery. However, in 1861 he enlisted in the Virginia Volunteers, a unit of horse-mounted infantry. Despite the politics of the conflict Mosby felt it was his patriotic duty fight for his country, stating, "the south was my country." This moral dilemma would reappear in his memoirs and letters after the war.

By 1862 Mosby was riding with Confederate cavalry forces commanded by James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart. He gained a reputation for being skilled at espionage and intelligence gathering. Mosby was briefly detained by the US army and held as a prisoner in Washington, DC.

Mosby's Rangers

In 1863 Mosby was given independent command of the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, a band of partisan rangers who operated outside of regular army norms. The rangers blended into the civilian population of Northern Virginia, had no camp duties, and successfully raided US supply lines. They often shared the spoils of their victories. This included cash, food rations, and weapons. Their success proved controversial within the Confederate Government as many army regulars thought it encouraged desertion from the front lines. The rangers operated extensively in the Shenandoah Valley and caused great levels of frustration during the 1864 campaign.

In April 1865, two weeks after Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Mosby disbanded the unit. While the rangers were paroled, Mosby's status was uncertain. Federal commanders argued the guerilla style conduct made him exempt from parole. An arrest order and bounty were placed on his head. Only when these were rescinded did Mosby surrender, becoming one of the last Confederate leaders to do so.

Post Civil War

Mosby returned to civilian life as a lawyer in Warrenton, Virginia. A most unusual friendship began between Mosby and Ulysses S. Grant. Mosby became active in politics, joined the Republican Party, and served as Grant's campaign manager during the 1872 presidential election. This infuriated southerners who viewed him as traitor to the Confederate cause. He received death threats, was the subject of vandalism, and the target of at least one assassination attempt. In 1878 President Rutherford B. Hayes, a former US officer who fought against Mosby in the Shenandoah Valley, appointed him as the United States Consul to Hong Kong. He also worked government jobs with the Department of Interior and Department of Justice.

Mosby pushed back against the Lost Cause. In 1894 Mosby made his point clear, writing, "I've always understood that we went to war on account of the thing we quarreled with the North about. I've never heard of any other cause than slavery."