Last updated: July 7, 2023

Person

Grace Lee Boggs

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Grace Lee Boggs was a Chinese American civil rights and labor activist. Her support for causes such as the Black Power movement, feminism, and the environment spanned over 70 years. Most of her activism was concentrated in Detroit, where she met her husband, James Boggs. Together, they became two of Detroit’s best-known activists. Throughout her life, Grace Lee Boggs maintained the core belief that if people worked together, they could accomplish positive social change.

What does it mean to be revolutionary? How about a "solutionary"?

Early Life and Education

Grace Lee Boggs’s experiences as a Chinese American woman alerted her to the need for social change in the United States. Boggs was born above her father’s restaurant in Providence, Rhode Island on June 27, 1915. Her parents were both immigrants from China.

Boggs became increasingly aware of racism after her family moved to New York City when she was 8. She grew up in Jackson Heights in Queens, New York. She and her family were the only Chinese people in the neighborhood. Boggs recalled feeling that she could not be Chinese and American at the same time. Nevertheless, her middle-class background afforded her opportunities. At 16 years old, Boggs began studying at Barnard College in Manhattan. She was one of only three students of color.[1] At the time, she felt unprepared and unclear about her path. In 1935, Boggs graduated with her bachelor’s degree in philosophy. She went on to earn her PhD in philosophy fro m Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania.[2]

m Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania.[2]

Early Activism

Employers refused to hire Boggs due to her gender and ethnicity. Years later, she remarked that “Even department stores would say, ‘We don't hire Orientals.’” She eventually got a job at the University of Chicago’s philosophy library. Although she was no longer unemployed, Boggs earned only a $10 weekly stipend. Because her pay was so low, she could not afford rent. Instead, she lived in a rat-infested basement for free.

Boggs’s involvement in revolutionary activism took off after she moved to Chicago. One day, she passed a group protesting inadequate living conditions among the poor, especially low-income African Americans. Those conditions closely resembled her own living situation. Boggs became involved with grassroots organizations that advocated for tenants’ and workers’ rights, such as the South Side Tenants Organization and socialist Workers Party. She later noted that this was the first time she connected with the African American community. “I was aware that people were suffering, but it was more of a statistical thing,” she explained. “Here in Chicago, I was coming into contact with it as a human thing.”

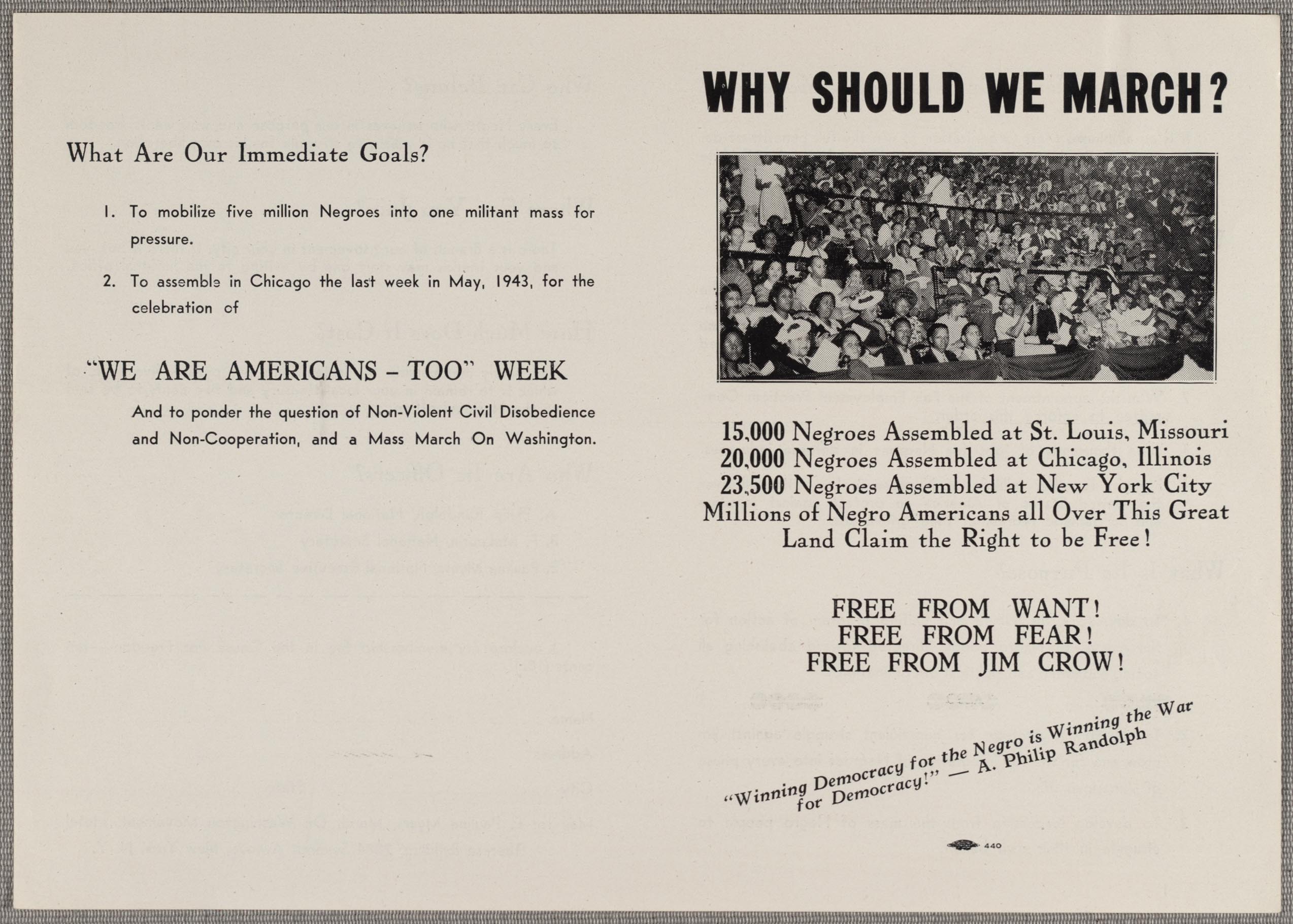

Through her work, Boggs also became involved with the proposed 1941 March on Washington. Organized by prominent African American labor unionist A. Philip Randolph, the march protested the segregation of the military and wartime manufacturing. Before the march could occur, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination in the U.S. defense industry, so Randolph called off the march. The Executive Order was an important step toward full desegregation. Becoming involved with the march and meeting Randolph helped Boggs realize what a movement could do.

Through her work, Boggs also became involved with the proposed 1941 March on Washington. Organized by prominent African American labor unionist A. Philip Randolph, the march protested the segregation of the military and wartime manufacturing. Before the march could occur, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination in the U.S. defense industry, so Randolph called off the march. The Executive Order was an important step toward full desegregation. Becoming involved with the march and meeting Randolph helped Boggs realize what a movement could do.

Under the name “Ria Stone,” Boggs became a central member of the Johnson-Forest Tendency, led by C. L. R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya. Named after its founders’ pseudonyms, the Johnson-Forest Tendency was a Marxist-Humanist subset of the Workers Party and later Socialist Workers Party. For twenty years, Boggs worked closely with James, a Trinidadian historian. Collaborating with James majorly influenced Boggs’s social theory.

Detroit Activism

During the 1950s, Boggs moved to Detroit and began editing the radical newspaper Correspondence, which supported worker-centered revolution. While working for the paper, she met auto worker and activist James “Jimmy” Boggs. They married in 1953. Until she met her husband, Boggs felt that her knowledge of revolutionary struggle had mostly come from books and theory, instead of the streets. The couple threw themselves into supporting the local community. They quickly gained prominence for their writing and grassroots activism, which advocated for workers, the poor, the hungry, the unemployed, the elderly, and revolution to support those causes.

The Boggses also protested in support of the civil rights and Black Power movements. When Malcolm X visited Detroit, he stayed at their home.[3] Grace Lee Boggs even tried to convince him to run for the U.S. Senate in 1964. James and Grace Lee Boggs’s home serves as the headquarters of the Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership, which supports activism and grassroots organizing on a local and national scale.

Social Change, Revolutionaries, and ‘Solutionaries’

During her doctoral studies, Boggs became interested in the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Immanuel Kant, Karl Polanyi, and Karl Marx. Their theories of social change inspired her approach to rooting out societal inequity. Although her ideas initially focused on revolution, Boggs promoted personal transformation, reflection, and community organizing rather than violence. As Boggs continued in her activism, her views on rebellion and revolution evolved over time. In an interview, she explained:

“What we tried to do is explain that a rebellion is righteous, because it’s the protest by a people against injustice, but it’s not enough. You have to go beyond rebellion. And it was a turning point in my life because until that time, I had not made a distinction between a rebellion and revolution. And it forced us to begin thinking, what does a revolution mean? How does it relate to evolution?”

In 1992, Boggs co-founded Detroit Summer, a community-based youth empowerment and engagement program. When her husband James died the following year, Boggs become even more involved in Detroit activism. Reflecting on her life with James and her work with the Johnson-Forest Tendency, Boggs began to shift away from revolution and toward “solutionaries.” She drew inspiration from the everyday struggles of the oppressed. From their strategies for survival, Boggs learned to identify and develop solutions to make life livable. She realized change had not come from within the government or from putting pressure on the institutions of power. In her last book, The Next Revolution, she stressed: “It is a time of deep change, not just of social structure and economy but also of ourselves. If we want to see change in our lives, we have to change things ourselves.”

Until she was 98, Boggs wrote a weekly column in the Michigan Citizen that promoted civic reforms. In 2013, Boggs established the James and Grace Lee Boggs School, a community-based charter school with a curriculum focused on Detroit. Months after her 100th birthday in June 2015, Boggs died on October 5, 2015.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Notes:

[1] The other two students of color at Barnard College were Louise Chin and Grace Ijima.

[2] Bryn Mawr College Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

[3] The Grace Lee and James Boggs House Historic District is locally designated in Detroit. Detroit is a Certified Local Government, a certified partnership program between federal, state, and local governments that supports local communities’ commitment to historic preservation.

Bibliography

Boggs, Grace Lee, and Ossie Davis. Living for Change: An Autobiography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Chow, Kat. “Grace Lee Boggs, Activist and American Revolutionary, Turns 100.” Code Switch. NPR. June 27, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/06/27/417175523/grace-lee-boggs-activist-and-american-revolutionary-turns-100.

Detroit Historic Designation Advisory Board. “The Proposed Grace Lee and James Boggs House Historic District: Final Report.” Detroit: City Council, 2011. https://detroitmi.gov/sites/detroitmi.localhost/files/2018-12/Grace%20Lee%20Boggs%20House.pdf.

McFadden, Robert D. “Grace Lee Boggs, Human Rights Advocate for 7 Decades, Dies at 100.” New York Times. October 5, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/06/us/grace-lee-boggs-detroit-activist-dies-at-100.html.

Moyers, Bill. Bill Moyers Journal: The Conversation Continues. New York: New Press, 2013.