Last updated: November 1, 2021

Person

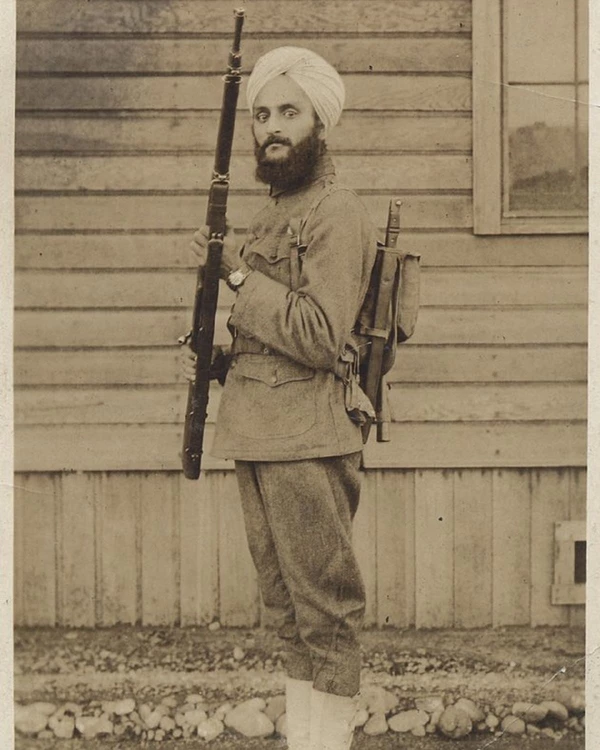

Bhagat Singh Thind

Public domain.

Bhagat Singh Thind was an Indian independence activist, immigrant to the United States, and World War I veteran. His quest for naturalization is a key part of the long struggle to remove racial barriers to U.S. citizenship.

Immigration and Political Activism

Bhagat Singh Thind was born in the Punjab region of India. He migrated to Seattle in 1913 to attend graduate school. He was one of around 7000 Indian men who arrived in the Pacific Northwest around this time. Many of them were Punjabi Sikhs who were fleeing civil unrest, disease, and repression by British colonial authorities in India. They sought economic and educational opportunities in the United States.

Thind studied religion and literature at the University of California, Berkeley.[1] He spent summers working at lumber mills in Astoria, Oregon. Asian immigrants faced considerable racial discrimination and violence. In 1907, a white mob in the town of Bellingham in Washington State attacked South Asian workers there, driving more than 100 of them away permanently.[2]

In Oregon, Thind worked with other Punjabis as well as workers from Europe, especially Finnish immigrants. Many of them had been involved in labor and political activism in their home countries. A radical political culture began to take root in the community. Thind joined the Ghadar Party, which organized Indian immigrants in North America and advocated the overthrow of British colonial rule. Its first meeting was held at the Finnish Socialist Hall in Astoria. “Ghadar” means “revolt” or “rebellion” in the Urdu language. British agents in Oregon knew about the Ghadar Party and spied on its members, including Thind. In 1914, some members of the group returned to India and attempted to incite an armed rebellion, which failed. Thind remained in the United States, but he stayed involved with the independence movement.

War Service and Citizenship Cases

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Bhagat Singh Thind enlisted in the U.S. Army. As part of his Sikh religion, he wore a turban and became the first turbaned soldier in the American military. Thind trained at Camp Lewis in Tacoma, Washington, and was honorably discharged in 1918.[3]

While he was in the army, Thind applied for U.S. citizenship. Initially, the court approved his petition. But the Bureau of Naturalization opposed it, and the court overturned its own order days later. At issue was the question of Thind’s race. The Naturalization Act of 1790 had stated that only “free white person(s)…of good character” could become citizens. Later laws and court decisions, especially the 14th Amendment and United States vs. Wong Kim Ark, expanded this group. But in the early 20th century, most Asian immigrants were still excluded from citizenship on the grounds that they were not white.

The next year, Thind applied for citizenship again, this time in Oregon. He argued that he should in fact be considered a white man. At the time, some anthropologists claimed to be able to divide the world’s population into distinct “races.” People from India were sometimes considered part of the “Caucasian race”—and Caucasian was also a synonym for “white.” The judge in Thind’s case decided that this was a strong enough argument. He also took into account Thind’s military service, and granted him citizenship in November of 1920.

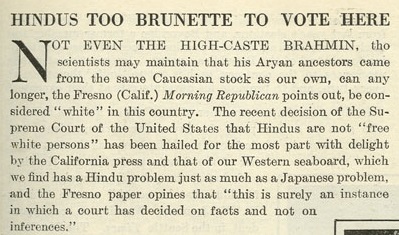

However, the Bureau of Naturalization still opposed Thind’s citizenship. They appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and asked the Court to rule on whether people from India counted as “white.” In 1923, the Court unanimously ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that the answer was no. The “common man” in the United States would not recognize Thind as white, and therefore he wasn’t. (The article above, like most press coverage of Thind's cases, describes all Indians as "Hindus" regardless of their actual religious beliefs.)

However, the Bureau of Naturalization still opposed Thind’s citizenship. They appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and asked the Court to rule on whether people from India counted as “white.” In 1923, the Court unanimously ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that the answer was no. The “common man” in the United States would not recognize Thind as white, and therefore he wasn’t. (The article above, like most press coverage of Thind's cases, describes all Indians as "Hindus" regardless of their actual religious beliefs.)

As a result of this decision, dozens of Americans from India lost their citizenship status. The Thind case shows how definitions of race could change over time and be subject to interpretation in ways that had real consequences for people’s lives.

Later Life

In 1935, Thind became a U.S. citizen for the third and final time after Congress granted legal status to all World War I veterans. It was not until 1940 that all people from India became eligible for naturalization.Thind became a writer and lecturer on philosophy and Sikh religion. He died in 1967.

Notes

[1] South Hall, the oldest building on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 25, 1982.

[2] Bellingham authorities cooperated with the mob by keeping the South Asian workers under “protective custody” in the basement of the town’s city hall on the night of the riot. The next day the mob drove them out of town permanently. Bellingham’s Old City Hall, now the Whatcom Museum, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 3, 1970.

[3] The historic Red Shield Inn, one of two surviving buildings from Camp Lewis, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 14, 1979. It is located in present-day Fort Lewis and currently houses the Lewis Army Museum.

Bibliography

Coulson, Doug. “British Imperialism, the Indian Independence Movement, and the Racial Eligibility Provisions of the Naturalization Act: United States v. Thind Revisited.” Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives 7 (2015): 1-42. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2610266

Coulson, Doug. Race, Nation, and Refuge: The Rhetoric of Race in Asian American Citizenship Cases. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2017.

Deslippe, Philip. “Bhagat Singh Thind in Jail.” South Asian American Digital Archive, Feb. 19, 2018. https://www.saada.org/tides/article/bhagat-singh-thind-in-jail

Lee, Erika. "Immigration, Exclusion, and Resistance, 1800s-1940s. In Finding A Path Forward: Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks Theme Study, ed. Franklin Odo. United States National Park Service.

Lopez, Ian Haney. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Ogden, Johanna. “Ghadar, Historical Silences, and Notions of Belonging: Early 1900s Punjabis of the Columbia River.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 113, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 164-197.https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/east_indians_of_oregon_and_the_ghadar_party/#.YJ19AqhKiUk

Shah, Nayan. Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality and the Law in the North American West. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012.

Snow, Jennifer. “The Civilization of White Men: The Race of the Hindu” in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. In Race, Nation, and Religion in the Americas, edited by Henry Goldsmith and Elizabeth McAlister, 259-280. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Article by Ella Wagner, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.