|

Valley Forge National Historical Park Chapter 4 |

|

|

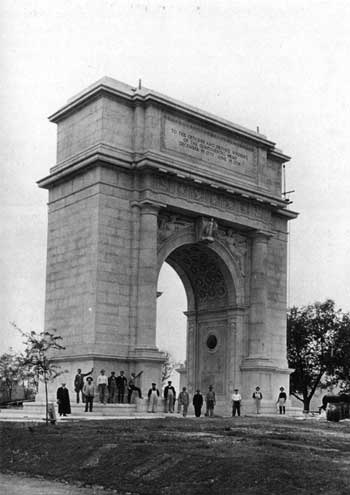

CHAPTER FOUR: The Park Commission Triumphs (continued) America was already at war by the time its national monument, the National Memorial Arch, was dedicated in 1917. The arch finally brought Valley Forge what the Valley Forge Memorial Association had really wanted—a gift from the entire nation to the historic campground. After the efforts of the Valley Forge Memorial Association had dwindled to a stop, the park commission had speculated about visiting Washington in 1894 to ask for a national monument on Mount Joy. The park commission envisioned "a colossal bronze figure of a private soldier on guard and looking down on the Old Gulf Road. He should be young in years, whose wan face, ragged uniform and worn out shoes would typify the hunger and cold so heroically borne in that historic camp." [97] What the park eventually got was something quite different. In 1908, Congressman Irving P. Wanger of Norristown introduced a bill in Congress to appropriate $50,000 for two federally funded arches at Valley Forge. These were to be christened the Washington and Von Steuben arches, and they were to be located at the two major entrances to the park. This expensive proposition occasioned some debate in Congress when other politicians questioned whether money should be spent on monuments at a time when the United States was forced to issue bonds to run the government. Democrats were generally against the expenditure, but Republicans argued that America was not yet so poor that she could not afford to be patriotic. [98] A Senate committee amended the bill by changing the two arches to a single arch honoring Washington, and so the national monument would be truly worthy of the nation's gratitude to the army at Valley Forge, they doubled the appropriation. The bill was approved in 1910, and Congress resolved that the secretary of war would oversee the project, approving plans and specs and authorizing the location of the arch. The arch was designed by Paul Philippe Cret, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Cret was born in Lyons, France, in 1876 and had studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts there and in Paris. He would remain affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania until his retirement in 1937 after a long and influential career as one of America's most respected architects. Cret is known today for his public buildings in the Beaux Arts style, which drew inspiration from the Renaissance and the work of classical antiquity. In the Philadelphia area, Cret's work includes the Federal Reserve Bank building, the Barnes Foundation museum, the Rodin Museum (with Jacques Greber), the Ben Franklin Bridge, the Henry Avenue Bridge, and the University Avenue Bridge, among others. Cret's final design for the arch drew its inspiration from the Arch of Titus in Rome. It had many directly derived ornamental details, such as its coffered ceiling and the winged female figures on its spandrels. In ancient Rome, triumphal arches had been constructed to honor victorious generals, so the idea of an arch honoring George Washington seemed appropriate even though the concept was anachronistic. The arch drew some early fire from the Philadelphia Record, where an editorial observed that Roman arches had always been part of the urban setting of Rome—a triumphal arch seemed ridiculous in a lonely rural landscape. [99] A second controversy arose when Congressman Wanger questioned the arch's location. The park planned to build the arch along the boulevard they had constructed along the outer line defenses. Wanger wanted it on Gulph Road where the Continental soldiers had left their bloody footprints as they marched into the area. [100] In 1911, Wanger wrote a bitter letter to the park superintendent, saying:

At the urging of the secretary of war, the commission met with Wanger and heard him out, but did not change the proposed location of the arch. [102] In 1914, when the arch was nearing completion, it was discovered that no money had been set aside for dedication ceremonies. The park commission hastily asked the War Department for funds, but officials there merely replied that the surplus of the original appropriation could be applied for the dedication. [103] When the park commission found that it had no money left, the secretary of war was asked to sponsor a bill appropriating $5,000 for suitable dedication ceremonies. By then, the United States had a new secretary of war, who responded that he had not initiated the building of the arch and did not plan to become involved. [104] This put the arch in limbo. Until a dedication officially transferred it to the care of the park commission, it did not belong to the park. And until the arch belonged to the park, no state money could be spent on its repair and maintenance. An article in the Philadelphia Public Ledger speculated whether the arch would long remain in this state, the forces of nature gradually transforming it from a classical arch to a classical ruin. [105] The arch was finally dedicated on June 19, 1917. A special train of Pullman cars brought an impressive number of U. S. Congressmen to Valley Forge, where they crowded onto and around a grandstand draped with bunting and American flags. [106] Professor Paul Cret could not attend because he was already on his way to France, where he served in the French army as an interpreter attached to the First Division of the American army. Pennsylvania's governor, Martin Brumbaugh, who for personal religious reasons did not sanction war, had a difficult time delivering a suitably patriotic speech that did not compromise his principles. Victory in Europe depended on the economic and emotional support of America. During World War I, antiwar sentiments could literally prove dangerous to the individual who uttered them. Brumbaugh spoke about "the spirit of Valley Forge," which he said was "with the Allies in the western line": "It is breathing hope in Russia. It has asserted itself in Greece. It is brooding over China and has already quickened Japan and animates the peoples of the islands of the Sea." His message was that the spirit of Valley Forge and its lesson of triumph through endurance would continue in those troubled times to bring hope to humankind. [107]

|

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Valley Forge ©1995, The Pennsylvania State University Press treese/treese4d.htm — 02-Apr-2002 | ||