Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

|

BIRCH COULEE BATTLEFIELD Minnesota |

|

| ||

The battle at this site near the junction of Birch Coulee and the Minnesota River, about 16 miles northwest of Fort Ridgely and just opposite the Lower, or Redwood, Sioux Agency, marked the high tide of the Sioux during their 1862 revolt. After killing hundreds of settlers in the Minnesota River Valley and attacking Fort Ridgely and New Ulm, on September 2 Chief Little Crow's Santee Sioux surrounded a force of 170 Volunteers under Capt. Hiram P. Grant. Col. Henry Hastings Sibley had sent them ahead from Fort Ridgely to reconnoiter the Redwood Agency, which the Indians had attacked the previous month, and to bury the dead. Besieged for 31 hours, the soldiers lost 22 killed and 60 wounded before the arrival of Sibley and reinforcements on September 3. The Indians, who had few casualties, fled.

A marker on U.S. 71 directs the visitor to the battlefield site, which is preserved in 32-acre Birch Coulee State Memorial Park. The rolling, tree-studded battlefield is relatively unchanged.

|

FORT RIDGELY and NEW ULM Minnesota |

|

| ||

This fort (1853-67) and town bore the brunt of the 1862 Minnesota Sioux uprising. They provided refuge for settlers from the Minnesota River Valley, and countered successive onslaughts. The fort also provided troops for the 1862-64 retaliatory campaigns of Gen. Henry Hastings Sibley westward into Minnesota and the Dakotas.

|

| Gen. Henry Hastings Sibley led the campaign against the Santee Sioux of Minnesota. Engraving by J. C. Buttre after a photograph by J. W. Campbell. (Library of Congress) |

The Spirit Lake Massacre of 1857, when some Santee, or Eastern, Sioux killed nearly 50 settlers just across the Minnesota border in Iowa, was a significant portent of future violence arising from Indian opposition to settlement on their lands. But, although the Sioux and Cheyennes raided periodically, the big explosion did not come until 1862. In August of that year the Santees of Minnesota went on the warpath under Chief Little Crow. After killing the whites at the Lower, or Redwood, Sioux Agency, his warriors swept up and down the Minnesota River Valley and slaughtered perhaps 800 settlers and soldiers, took many captives, and inflicted immense property damage. Refugees from the valley swarmed into Fort Ridgely, about 12 miles below the agency, and New Ulm, a German settlement 15 miles farther south down the valley from the fort.

Sending a courier to Fort Snelling for reinforcements, Capt. John S. Marsh left a skeleton guard at Fort Ridgely and set out for the agency with 45 men and an interpreter. Just before he reached there, an overwhelming force of Indians struck. In a running fight back to the fort, half the soldiers died, including Marsh. More refugees poured into the fort. When about 400 Sioux attacked on August 20, and 2 days later about twice that number, the artillery and rifle fire of the 180 Volunteer and civilian defenders beat off repeated charges. Their casualties heavy, the Indians finally abandoned the effort.

While the main body of warriors was preparing to attack Fort Ridgely, on August 19 about 100 had raided New Ulm, whose normal population of 900 had been swollen to 1,500 by the influx of refugees. Judge Charles E. Flandrau, a leading citizen, organized a defense force of about 250 poorly armed men. After putting three houses to the torch, the Indians withdrew. Four days later, having failed to take Fort Ridgely, 650 warriors again moved against New Ulm. They drove the defenders from the outskirts and occupied outlying houses. Fighting raged back and forth throughout the day. Finally, Flandrau and 50 men charged, forced the Indians from the houses, and burned them. Deprived of these shelters, the Sioux departed. In New Ulm about 34 settlers lost their lives and 60 suffered wounds; fire destroyed 190 buildings. Indian losses are not known. That same month, farther west, the Sioux launched a series of attacks on settlers in the region of Fort Abercrombie, N. Dak., and the next month besieged the fort.

As soon as news of the Little Crow uprising reached St. Paul, Gov. Alexander Ramsey commissioned his predecessor, Henry Hastings Sibley, as a colonel in the State militia to put it down. Assembling all the Volunteer troops who had not been sent off to the Civil War, Sibley advanced up the Minnesota River at the head of nearly 1,500 men and on August 28 arrived at Fort Ridgely. On September 3 the command relieved a 170-man detachment that Sibley had sent on August 31 to reconnoiter the Redwood Agency and bury bodies. The detachment had been besieged for 31 hours by a large band of Sioux at Birch Coulee, about 16 miles northwest of Fort Ridgely.

|

| Chief Little Crow, leader of the Minnesota Sioux uprising. (photo by A. Zeno Shindler, Smithsonian Institution) |

On September 19 Sibley and 1,400 Volunteer troops set out from the post. Four days later they managed to escape the full brunt of an ambush and won a decisive victory over Little Crow in the ensuing Battle of Wood Lake, Minn. The Minnesota outbreak ended, though many of the Sioux, including Little Crow and another principal leader, Inkpaduta, fled westward into Dakota rather than surrender.

Sibley imprisoned 2,000 warriors and tried them before a military court. Of more than 300 sentenced to die, President Lincoln pardoned most of them. In December the Army publicly hanged 38 at Mankato. The following June, near the town of Hutchinson, settlers killed Little Crow, who had slipped back into Minnesota to steal horses.

The Santees who had eluded Sibley's troops and fled to Dakota joined forces with the Teton Sioux, belonging to the Western, or Prairie, Sioux. In the spring of 1863 Sibley, now a brigadier general, gave pursuit from Fort Ridgely. Spending the summer campaigning, he won victories in July in North Dakota at the Battles of Big Mound, Dead Buffalo Lake, and Stony Lake. Sibley followed the survivors to the Missouri River, which he reached on July 29, and then returned to Minnesota.

Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully had intended to unite with Sibley in a joint campaign, but low water delayed his journey up the Missouri River from Sioux City, Iowa. Sully nevertheless carried on and defeated the Indians in the Battle of Whitestone Hill, N. Dak. (September 1863), and after wintering on the Missouri River near present Pierre, S. Dak., in the Battle of Killdeer Mountain, N. Dak. (July 1864). By this time the Sioux coalition, which had never been very cohesive and which had suffered heavily, had been disbanded.

Fort Ridgely State Park is surrounded by essentially unimpaired prairie and woodlands. Archeological excavations in the 1930's revealed the building foundations, some of which were stabilized and left exposed and are still preserved today. A log powder magazine has been reconstructed. A restored stone commissary building houses a small museum that interprets the history of the fort, along with various markers. The scene of the fighting in the western outskirts of the modern city of New Ulm has been completely changed by urban expansion. At the Lower Sioux Agency site, the Minnesota Historical Society is creating a center to interpret the Sioux war of 1862.

|

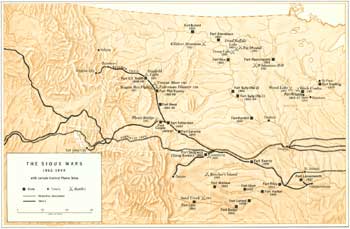

| The Sioux War (1862-1868). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

LAC QUI PARLE MISSION Minnesota |

|

| ||

Established in 1835 by the Presbyterian Church among the Sioux, this mission housed one of the first Indian schools west of the Mississippi. The mission's founder, Rev. Thomas S. Williamson, and his coworkers devised a phonetic system and translated the Christian Gospels and other works into the Sioux language. They also helped Rev. Stephen R. Riggs compile the first grammar-dictionary in the tongue, published in 1852 by the Smithsonian Institution. The mission was abandoned the following year. The reconstructed log chapel and school (1835) is part of Lac Qui Parle State Park.

|

SIBLEY (HENRY HASTINGS) HOUSE Minnesota |

|

| ||

Perhaps Minnesota's most famous old house and the first in the State constructed of stone, this residence is of architectural and historical interest. Henry Hastings Sibley (1811-91), pioneer fur trader and later the first Governor and commander of Volunteer forces during the Sioux uprising of 1862, erected it in 1835. The year before, as the local bourgeois for the American Fur Co., he had arrived as a young man of 23 at the thriving fur trade town of St. Peter's, known as Mendota after 1837. Opposite Fort Snelling at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, it was the first permanent white settlement in Minnesota and the focal point of the Red River fur trade. Marrying in 1843, Sibley brought his wife to the home, where nine children were born to them. The leader in making the town a business and cultural center, Sibley entertained many celebrities in his home, where Indians also frequently visited to trade. In time, Minneapolis and St. Paul gained the ascendancy over Mendota, and in 1860 the Sibley family moved to St. Paul.

The Daughters of the American Revolution owns the house, restored by the Sibley House Association, and several outbuildings. Of native stone with white wood cornices and trim, the large two-story home represents the colonial style and closely resembles many of the stone residences in Pennsylvania and the Western Reserve territory in Ohio. In excellent condition, it is furnished with period pieces, some of which belonged to the Sibley family.

|

| Henry Hastings Sibley House. (photo by E.D. Becker, Minnesota Historical Society) |

|

WOOD LAKE BATTLEFIELD Minnesota |

|

| ||

The so-called Battle of Wood Lake, which followed the Army disaster at Birch Coulee, Minn., was the first decisive defeat of the Sioux in the Minnesota uprising of 1862 and marked the end of the campaign there. Col. Henry Hastings Sibley set out from Fort Ridgely on September 19 in command of 1,400 Volunteers. Near Wood Lake on September 23 they managed to avoid an ambush by Chief Little Crow and 700 braves, and in the ensuing battle killed 30 Indians and wounded many more. In contrast, Army casualties were seven dead and 30 wounded. Six days later Sibley won a brigadier general's star.

The State preserves an acre of the battlefield, which contains a monument. Cultivated fields dot the gently rolling prairie terrain. Lone Tree Lake, where the battle actually took place, has disappeared since 1862. Sibley's guide mistook it for Wood Lake, several miles to the west, hence the misnomer.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/sitec6.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005