Historical Background

With the collapse of the Apaches, all the western tribes had yielded to the realities of their condition and settled on reservations. Military action had hastened the process, but the absence of any acceptable alternative for the Indians, given the loss of their land and traditional means of livelihood, provided the most powerful incentive. At first the reservation was simply an expedient. The problem was to clear the paths of expansion. The solution was to corral the Indians on a parcel of land that—as yet—no one else wanted, and keep them reasonably content by regular issues of food and clothing. But during the decade of the 1880's the reservation system assumed a different shape. Abolition of the treaty system in 1871 had deprived the tribes of even the small comfort of theoretical sovereignty. Thus when they came to the reservation, fresh from military conquest and dependent on Government largess, they were undeniably wards of the Government and subject to its will.

|

| Geronimo, Natchez, and followers en route in 1886 from Fort Bowie, Ariz., to Fort Pickens, Fla., for imprisonment. Geronimo is third from right, bottom row; Natchez, fourth from right. (photo by A. J. McDonald, National Archives) |

|

| The ultimate humiliation for the Indians, once a proud people, was the reservation dole. Distribution of rations about 1892 at San Carlos Agency, Ariz. (National Archives) |

In the 1880's this will derived largely from the theories of a growing number of Indian reform organizations that exerted increasingly awesome influence on national legislators and administrators. The reformers expressed the widespread conviction that solution of the Indian problem lay in transforming the Indian, as rapidly as possible and by compulsion if necessary, into a God-fearing tiller of the soil enjoying the blessings of Christianity, education, individual instead of tribal ownership of land, and national citizenship. Reformers and like-minded officials used the reservation system as the instrument for attempting this program. Thus, in the end, the reservation system wrought with terrible swiftness the ethnic disaster that had been foreshadowed by the collapse of the "Permanent Indian Frontier."

On the reservation the Indian found himself suddenly overwhelmed by the civilizing process. It took the form of a concerted campaign to root out the old and inculcate the new. Indian policemen and Indian courts, controlled by the agent, ironically provided the compulsion. When they failed, withholding of rations ordinarily produced a surface illusion of the desired conformity.

|

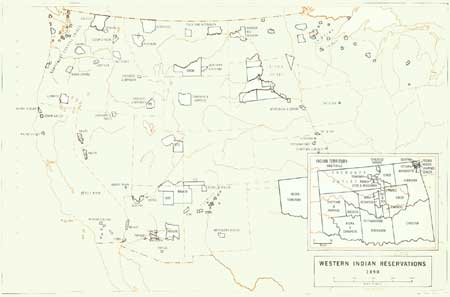

| Western Indian Reservations (1890) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

All facets of Indian life came under fire. Because tribal communalism stood in the way of progress, the attack centered on basic social, economic, religious, and political institutions. Many of these, indeed, had already lost much of their pertinence in the transition from nomadic to sedentary life. "Every man a chief," announced the Government, and urged the people to abandon their camps, throw away their lodges, spread out over the reservation, build cabins, and ignore the traditional leaders. A list of "Indian Offenses," promulgated by the Indian Bureau, outlawed fundamental social and religious customs. These included the Sun Dance, the foundation upon which the Plains Indian had built his whole theological edifice, and the practices of the medicine man.

|

| Reading the Declaration of Independence at Rosebud Agency, S. Dak., on the Fourth of July 1897. Those few Indians who understood the significance of the occasion must have recognized the terrible irony involved for their people. (photo by J. A. Anderson, Library of Congress) |

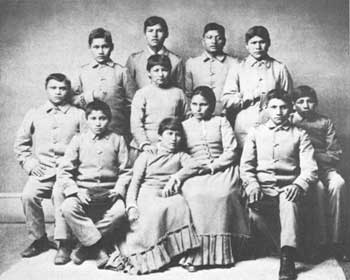

Other whites helped the agent. They were a different breed than the easy-going fun-loving trappers of earlier times. The "practical farmer" tried to teach farming to a people who did not want to farm, on land that for the most part was not suitable for farming anyway, using techniques that were ill adapted to the soil and climate and to the background of the trainees. The school teacher tried to teach unwilling children of unwilling parents the "useful arts of civilization," but these arts had little real meaning in the reservation environment. Off-reservation boarding schools, patterned after the military model of Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, proved much more effective—until the child returned to the reservation and found no place for himself either in white or Indian society. Missionaries tried to substitute a frequently irrelevant Christianity for religious patterns that had proved rich and satisfying and that were a functional part of Indian culture. The Indians were often receptive to Christian teachings but also unwilling to surrender the old beliefs. They found that the trader was frequently the only entirely agreeable white man on the reservation. He provided them useful manufactures without eternally carping about their "barbarous" habits.

Central to the reform program was the severalty movement. Give the Indian individual title to the soil, reformers held, and virtually all other problems would automatically solve themselves. The Indian would become a responsible, self-supporting citizen just like all other citizens. The severalty movement culminated in the Dawes Act of 1887, which provided for the allotment of reservation lands, usually in 160-acre parcels, to individual natives. The Dawes Act gave eastern reformers and western land "boomers" common ground, for it provided that all reservation lands not needed for allotment could be thrown open to white settlement. Because the majority of western Indians at first resisted allotment, vast tracts of "surplus" reservation land were released for settlement before many Indians received allotments.

|

| Educational programs for the Indians in the 19th century stressed remaking them in the white man's image. Chiricahua Apache students, 4 months after entering Carlisle Indian School, Pa., in 1887. (Yale University Library) |

Loss of reservation land created deep resentment. Worse, after the Indian finally bowed to the inevitable and accepted allotment, he found himself imprisoned by a vicious and unfamiliar system that forced him ever lower on the economic scale. Eastern land patterns dictated 160-acre allotments. In the arid West these were too small for economic efficiency, especially when devoted to crop raising. Even these were severely reduced. Despite legal safeguards, patented land found its way, through one subterfuge or another, into white ownership. And the rest was endlessly subdivided through inheritance into tiny patches, on which the heirs eked out the barest subsistence.

Yet the policies of the 1880's, founded on the idealistic dreams of the severalty advocates, prevailed until well beyond the turn of the century.

Already, however, the "civilization" program and the beginnings of the severalty movement had produced severe emotional stresses among the tribes. A decade of exposure to reservation policies served mainly to blend twisted remnants of the old life with a few frayed strands of the new. Bleak prospects for the future combined with nostalgic memory of the past to induce a state of mind particularly susceptible to the Messianic fervor that swept the western reservations in 1889 and 1890. A strange mixture of Christian and traditional beliefs, the Ghost Dance religion promised a return of the previous order and the disappearance of the white race. The disastrous clash of arms at Wounded Knee Creek, S. Dak., December 29, 1890, shattered this dream and marked the final collapse of the Indian barrier.

In little more than a century the white man had reorganized the culture of the western Indians. But the forces of change flowed in both directions. Because he won the contest, the white man did not have to bow to a conqueror's will; thus his way of life under went no such cataclysmic change as that of the Indian. Yet his experience with the Indian, an experience not confined to the West and in fact spanning five centuries and a continent, left him in the 20th century with a culture decidedly influenced and enriched, in some ways profoundly, by the very culture he almost destroyed.

Phillips D. Carleton observed that the whites "conquered the Indian but he was the hammer that beat out a new race on the anvil of the continent." And D. H. Lawrence added, "Not that the Red Indian will ever possess the broadlands of America. But his ghost will."

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro9.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005