Historical Background

In northern California an attempt to place a Modoc band on an Oregon reservation precipitated the Modoc War (1872-73). The Modoc leader, Captain Jack, took his followers into the natural fortress of the lava beds bordering Tule Lake and held off a be sieging force for 5 months. During a peace conference in April 1873, the Modocs killed Gen. Edward R. S. Canby and another emissary. Not until late May did Captain Jack surrender. He and three others died on the gallows.

|

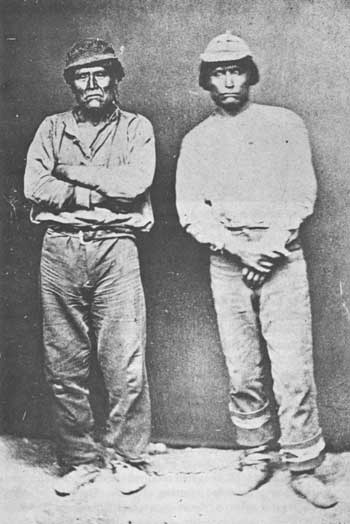

| Despite courageous resistance, Captain Jack, right, and his people lost the Modoc War (1872-73). Schonchin, chained to Jack, was one of three lieutenants who died with him on the gallows. (photo by L. Heller, Smithsonian Institution) |

From Indian Territory, where the southern Plains tribes had been given reservations, Kiowas and Comanches continued to raid in Texas. The Army chafed under Peace Policy restrictions that barred them from punishing Indians on their reservations. When the Government finally lifted this ban in 1874, Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes, and a few Arapahos fled westward to the Staked Plains of the Texas Panhandle. General Sheridan loosed columns on this area from Fort Bascom, N. Mex., Forts Concho and Griffin, Tex., Fort Sill, Okla., and Fort Hays, Kans.

The resulting Red River War lasted through the autumn and winter of 1874-75 and involved 14 engagements. The most notable were the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, Tex., in which Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie smashed a Comanche camp; and the Battle of McClellan Creek, Tex., in which Col. Nelson A. Miles routed a Cheyenne force. But it was sustained military pressure during the winter months, rather than clashes of arms, that disheartened the fugitives and led them, in the spring of 1875, to straggle back to their agencies and surrender—for the final time.

The Sioux and Cheyennes had been settled on a huge reservation west of the Missouri River in Dakota. But, as a price for the peace arranged in 1868, they had retained the Powder River country to the west as unceded hunting grounds. There, comfortably distant from the agencies, many Sioux and Cheyennes continued to enjoy their traditional life. Occasionally they raided settlements in Montana and along the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1873 the Northern Pacific Railroad survey up the Yellowstone River Valley raised the specter of another railroad along the fringe of the unceded hunting grounds. In 1874 discovery of gold in the Black Hills, a part of the Great Sioux Reservation, set off an invasion of miners and a Government effort to buy the hills from the Sioux. These events led to the Sioux War of 1876-77, a scarcely disguised attempt to clear the unceded territory of Indians and to frighten them into ceding the Black Hills.

|

| The Custer Expedition, shown here on its way to the Black Hills in 1874, confirmed rumors of gold there and spawned a wild rush onto the Great Sioux Reservation that the Government could not control. New warfare broke out on the northern Plains. (National Archives) |

|

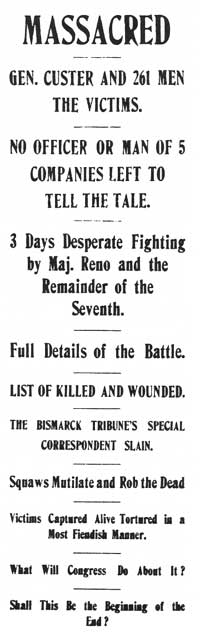

| Headlines such as these, from the Bismark Tribune Extra (July 6, 1876) carrying the first newspaper account of the Custer debacle, appalled the Nation and generated retaliatory campaigns that virtually ended Indian opposition on the northern Plains. (National Park Service) |

Again General Sheridan sent converging columns—under Gen. George Crook, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, and Col. John Gibbon—into the Indian country. Crook suffered two reverses, at the Battle of Powder River, Mont., on March 17, 1876, and at the Battle of the Rosebud, Mont., on June 17. Terry and Gibbon joined on the Yellowstone and designed their own convergence. They suspected that the enemy was in the Little Bighorn Valley. They did not suspect that Sitting Bull and other chiefs had brought together an unprecedented gathering of Sioux and Cheyennes, numbering perhaps 3,000 to 5,000 fighting men. Terry's subordinate, Custer, attacked this aggregation on June 25. He and more than 200 officers and men were wiped out. The balance of the regiment endured a 2-day siege before the approach of Terry and Gibbon caused the Indians to withdraw.

In this stunning victory, however, lay the roots of Indian defeat. The Nation demanded that Custer's death be avenged, and the Army poured troops into the Sioux country. The alliance of tribes fragmented, and through the winter General Crook and Colonel Miles hounded them across the frozen land. By spring, after several battles and great suffering, most of the Sioux and Cheyennes had returned to their agencies. Only Sitting Bull scorned surrender. He and some diehard followers took refuge in Canada. They held firm until 1881, when hunger at last compelled their capitulation.

The mountain tribes—Nez Perce, Ute, and Bannock—also attempted to resist the reservation system. The Nez Perces in particular caught the imagination and sympathy of the Nation. After years of procrastination, the nontreaty portion of the tribe, one of whose spokesmen was the statesmanlike Chief Joseph, acquiesced in the Government's attempt to place them on the Idaho reservation accepted by the rest of the tribe in 1863. But en route a few angry warriors killed some settlers, and the war was on. At White Bird Canyon and Clearwater in June and July 1877, the Nez Perces threw back Gen. Oliver O. Howard's soldiers. Then they turned eastward, over the Bitterroot Mountains. In 2-1/2 months, burdened with their families, they traveled 1,700 miles and con founded 2,000 soldiers. At Big Hole, Clark's Fork, and Canyon Creek, they beat off attacks. But at the Bear Paw Mountains, only 40 miles from the Canadian refuge at which they aimed, Colonel Miles cut them off and after a costly 6-day siege compelled them to surrender. More than 400 captives were ultimately sent to a reservation in Indian Territory.

One of the most violent expressions of Indian resentment against the reservation system occurred at Colorado's White River Agency in September 1879. Agent Nathan C. Meeker's zealous efforts to make farmers out of his Ute charges brought them to the brink of rebellion. When he called for military help, the Utes killed him and part of his staff, burned the agency, and set forth to meet the troops. At Milk Creek they ambushed a cavalry command en route to the agency. The commander, Maj. Thomas T. Thornburgh, died and in a weeklong siege the 150-man force suffered heavy casualties. A relief column drove off the Utes, and the revolt collapsed.

By 1880 peace had come to the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, and the Pacific slope. Only in the Apache country of the Southwest did fighting continue. Since Spanish and Mexican times, the Apaches had regularly raided the settlements of the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico as well as those of the Mexican states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Sonora. Americans who began arriving in the Southwest after the Mexican War found that the Apaches seldom discriminated. Military operations of the 1850's and 1860's in western Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona seemed only to aggravate the chronic menace.

The Apaches had cause to remember two military acts for years. In 1861, in Arizona's Apache Pass, a young lieutenant attempted to arrest Cochise for an offense he probably had not committed and drove him to implacable hostility. And in 1863 some of General Carleton's troops induced the equally renowned Mangas Coloradas to surrender, then murdered him.

After a decade of fearful bloodshed, in 1872 Gen. Oliver O. Howard, acting as a Peace Policy emissary, persuaded Cochise to call off the war he had loosed in retribution for the Apache Pass affair. General Crook's Tonto Basin campaign (1872-73) brought a period of calm to central Arizona. However, Crook's reassignment in 1875, coupled with a movement to consolidate all Apaches on the San Carlos Reservation, spread unrest. Among the more determined in their opposition were Victorio and Geronimo. But, after 2 years of warfare that swept across southern New Mexico, western Texas, and northern Mexico in 1879-80, Victorio was slain in a battle with Mexican troops. Geronimo proved more elusive.

The Apaches made especially formidable antagonists because, besides their unusual skill at guerilla warfare, they could take refuge from U.S. troops in the mountains of northern Mexico. To cope with this situation, the Army reassigned General Crook to Arizona in September 1882. Two months earlier Geronimo and 75 followers had fled the San Carlos Reservation. From bases high in the Sierra Madre they were terrorizing Arizona settlements. Crook, an advocate of unconventional methods, organized units of Apache scouts and, under the cloak of a diplomatic agreement with the Mexican Government, sent them into the mountain recesses that hid the fugitives. Months of exhausting campaigning followed, but by the spring of 1884 most of them had been coaxed back to the reservation.

|

| Geronimo surrendering to Gen. George Crook at Cañon de los Embudos, Mexico, in March 1886. Before reaching Fort Bowie, Ariz., however, most of the Chiricahua Apaches fled. Geronimo is third from the left, and General Crook second from right. (Library of Congress) |

Once more, however, in May 1885 Geronimo led an exodus to Mexico. Again Crook sent his scouts south of the border. Again persistence won out. Geronimo met him in council in March 1886 and agreed to surrender. En route to Fort Bowie, however, he and his followers broke for the mountains. Discouraged, his methods questioned by higher authority, Crook asked to be relieved. Gen. Nelson A. Miles took his place. Using much the same approach as Crook, Miles' officers again maneuvered Geronimo into a council, and in September 1886 he formally surrendered to Miles at Skeleton Canyon, Ariz. To insure an end to Apache outbreaks, he and his people were imprisoned in Florida.

|

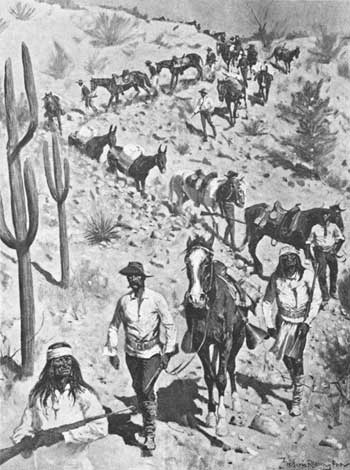

| Frederic Remington's portrayal of Capt. Henry W. Lawton's command pursuing Geronimo in the rugged wilds of Mexico's Sierra Madre during 1886. (Smithsonian Institution) |

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/soldier-brave/intro8.htm

Last Updated: 19-Aug-2005