|

Montezuma Castle National Monument |

|

|

Chapter 3

A CHALLENGE IN PRESERVATION The Early Management of the Monument

The passage of the Antiquities Act and the establishment of Montezuma Castle National Monument on 8 December 1906 extended to the site official designation as a point of national interest and nominally promised a greater degree of protection. However, these measures resulted in few practical changes in the day-to-day management of the ruins. Although the Antiquities Act contained provisions for the protection of archeological resources on public lands, including national monuments, it did not give specific information about the management of such sites and offered little guidance as to the enforcement of the new regulations. Further, Congress did not appropriate funds for the administration of the national monuments. The newly established monuments received inadequate protection at the beginning of the century, and many years passed before the preservation of these sites approached the intentions of the designers of the law. The Antiquities Act charged the General Land Office, Forest Service, and War Department with the responsibility for national monuments located on lands within their jurisdiction. These departments already had limited resources and staffs, and could hardly afford to take on the added responsibilities of overseeing national monuments. As a result, the monuments received only minimal attention, often in the form of infrequent inspection trips and posted warning signs. Although these actions did little to discourage vandals and looters from damaging sites and stealing artifacts, the establishment of national monuments did prevent law-abiding citizens from knowingly exploiting their resources. Unfortunately, however, many visitors were unaware of the special status of the monuments and continued to engage in destructive behavior. Without signs clearly indicating monument designation and formal supervision by trained personnel, the monuments continued to suffer damage and the loss of their unique resources. [1] At Montezuma Castle, similar problems of administration marked the first two decades of the site's existence as a national monument. When the GLO drafted legislation for the establishment of Montezuma Castle National Monument, the acting commissioner recommended that responsibility for the site be assigned to the GLO special agent in charge of the surrounding district and to the register and receiver of the local land office. [2] In this way, the GLO could provide official, albeit negligible, protection to the ruins without devoting considerable funds or resources to the cause. Although the Castle was located within the district of the proposed Rio Verde Forest Reserve, the establishment of the national monument superseded this temporary withdrawal and provided for the formal protection of the site. Because the forest reserve was never permanently established (the withdrawn lands, with the exception of the 160 acres forming Montezuma Castle National Monument, were restored to the public domain on 16 May 1910 by order of the secretary of the interior), the GLO resumed responsibility for the ruins upon the proclamation by President Theodore Roosevelt on 8 December 1906. [3] The GLO commissioner appointed F. C. Dezendorf, chief of special agents in Arizona and New Mexico, in temporary charge of the national monuments on lands within the jurisdiction of the Santa Fe office. [4] In addition, the GLO designated the register and receiver of the U.S. Land Office in Phoenix as the temporary custodians of Petrified Forest and Montezuma Castle National Monuments. In his letter of appointment to the Land Office officials, the commissioner instructed them to "refuse all entries offered to be made within these reservations, and in general, exercise, in conjunction with the Chief of Special Agents, such supervision as will aid in preserving these monuments or in insuring such authorized exploration, excavation, and removal of prehistoric relics as the law and regulations provide." He included with these instructions a copy of the regulations approved by the secretaries of war, agriculture, and interior regarding the issuance of permits for exploration, excavation, and collection at national monuments. [5] With these meager directions, the GLO ordered the ad hoc custodians to supervise and look after the newly created monument. No documents exist pertaining to these officials' administration of the site, but it appears that Montezuma Castle received little formal consideration and care for the next several years. During the early decades of the twentieth century, GLO officials did not rank the national monuments as high priorities. Without a bureaucracy to oversee the administration of these sites and with little staff and resources to spare for preservation activities, the agency sought ways to provide them nominal protection at minimal expense. The appointment of its officials as custodians of national monuments allowed the GLO a way to get by with this makeshift system of preservation. However, the agency's superficial efforts to protect the ruins at Montezuma Castle did little to reduce vandalism and the theft of artifacts; within a few years, the damage and abuse visitors had inflicted on the ruins again attracted the attention of concerned citizens. In her diary account of a family trip to the Verde Valley in 1907, Lucy Jones described the group's ascent into Montezuma Castle and their explorations of its interior. She noted the numerous names written on the walls and timbers of the ruins and admitted that members of their party added their names on the prehistoric edifice. [6] Although few accounts of the condition of the Castle at this time survive today, it seems likely that other visitors engaged in similar destructive behavior. In the absence of active preservation efforts and the regular supervision of the monument by an on-site custodian, the ruins thus faced continued threats of damage and vandalism. Taylor P. Gabbard, the superintendent and special disbursing agent of the Indian School at Camp Verde, echoed Jones's concern. In his letter to the secretary of the interior of 5 November 1911, he expressed his anxiety about the lack of protection for the cliff dwelling. [7] In response, Chief Executive Officer Clement Ricker of the Department of the Interior notified Gabbard that the general supervision of the monument was entrusted to Gratz W. Helm, a GLO special agent stationed at Los Angeles. Ricker acknowledged that this arrangement, although not effective from the standpoint of the protection of the ruins, was the most practical in light of Congress's failure to appropriate funds for the administration of the national monuments. He suggested that Gabbard file a report on the present condition of the ruins and any other information that would be of interest to the department. In addition, Ricker inquired if Gabbard would be able to look after the ruins in addition to his duties as superintendent of the Indian School; as one who resided closer to the site, Ricker reasoned, Gabbard could surely provide better care for the ancient monument than the present agent in charge. [8] By this time, it had become clear that Montezuma Castle, like the other national monuments, suffered from neglect. The establishment of the monuments and their recognition as places of national interest and value represented the extent of federal action at these sites. The Department of the Interior set up no formal administrative process to ensure the upkeep of the monuments under its care and did not provide funds for their protection. Thus, monuments such as Montezuma Castle languished as a result of the government's empty promises of preservation. It was only after advocates and boosters made continued efforts on behalf of the sites that the federal government began to take a stronger interest in the national monuments and to establish an organized system for their protection and administration. [9] More than two and one-half years after Taylor Gabbard's initial inquiry into the preservation efforts at Montezuma Castle, the Department of the Interior attempted to capitalize on his interest in the site. Assistant to the Secretary Adolph Miller wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs to determine whether Gabbard or his successor would be able to accept the duties of custodian of Montezuma Castle National Monument. In a statement that revealed the department's attitude about the preservation activities at such sites, Miller wrote, "Inasmuch as there is no appropriation available for protection of the Montezuma Castle National Monument, the service required as custodian of the monument from Mr. Gabbard will, of course, not make heavy inroad upon his time." [10] The department appeared more concerned about the appointment of a site custodian than the quality of care provided. It is unclear whether the lengthy delay between Gabbard's first letter and the request for his services corresponded to the low priority of the national monuments for the Department of the Interior or to difficulties encountered by Special Agent Helm's long-distance supervision of the Castle. In either event, the commissioner of Indian Affairs brought the matter of monument custodianship to Gabbard's attention. In a clearly thought-out response, Gabbard indicated that he took no action to help preserve the Castle in 1911 because it would have been pointless without money for materials, labor, and other expenses. He struck at the heart of the issue, stating that he would be willing to look after the ruins "provided that sufficient funds for that purpose can be secured. But without funds it is impossible for the Superintendent of the Camp Verde Indian School or any other person, to protect and preserve the Montezuma Castle which is now in need of substantial ladders and other necessary repairs." [11] Gabbard's reference to the need for repairs suggests that previous supervision of the ruins did not provide adequate protection. In addition, he understood that the token gesture of assigning a custodian to look after the Castle without the expenditure of funds for repair work amounted to a futile and meaningless preservation policy. Officials from the Department of the Interior paid little immediate attention to Gabbard's insights on the protection of the ruins; as a result, Montezuma Castle continued to suffer from official neglect. The department merely asked Gabbard to make an inspection of the Castle and to file a report on the repairs and improvements he thought necessary, including a list of estimated costs. [12] Around this time, Special Agent Helm arranged for GLO mineral examiner Roy G. Mead to make an inspection trip and report on the condition of the ruins. Mead's report to the GLO commissioner, dated 29 May 1914, sheds light on the immediate impact of GLO neglect of Montezuma Castle. Among his observations of the monument, Mead noted the unsafe condition of the wooden ladders providing access to the cliff dwelling, the deterioration of interior walls as a result of the removal of lintels over doorways, and visitors' defacement of walls and timbers. He also indicated that a section of the front wall had weakened considerably and was likely to fall at any time, resulting in significant harm to the rest of the structure (figure 15). Mead recommended that immediate action be taken to make repairs in order to protect the ruins against further damage. He urged the commissioner to authorize funds to stabilize the front wall using iron tie rods and cement, install new ladders for safe and easy entry into the ruins, and place a register inside the Castle "so that visitors could leave their names instead of using the walls for that purpose." [13]

Mead estimated these repairs would cost more than one hundred dollars. However, he offered these measures as a means to correct only the damage already done to the Castle. To protect the ruins against further destruction at the hands of visitors, the GLO needed to establish a better system of supervision. Mead suggested that naming a custodian in the vicinity of the monument would be the only way to prevent future acts of vandalism. By the time of his inspection trip, unscrupulous visitors had already removed "every fragment of pottery," taken timbers from within the structure, and written their names on the Castle walls. Mead emphasized the potential for new threats to the ruins: "A fine automobile road has recently been constructed from Prescott to Camp Verde, a small settlement three miles west of the Castle; and the trip from Prescott to the Castle and return can now be comfortably made in one day." Mead also reported that two garages in Prescott offered guided visits to the Castle. The garages charged parties between twenty-five and thirty dollars for the trip by car and for the service of the driver/guide. [14] This reference to tours represents the first documentation of interpretation at Montezuma Castle, but it also suggests the increasing popularity of the monument as a tourist destination. As greater numbers of people visited the unprotected monument, more destruction and vandalism could be expected. Unfortunately for Montezuma Castle, the pattern of delay and empty promises continued for some time. Other reports and letters from concerned individuals did little to persuade the GLO to set aside funds for the repair and protection of the monument. Such correspondence underlined the worsening condition of the ruins as a result of increasing visitation and the lack of supervision. Letters sent to GLO and Department of Interior officials echoed previous recommendations that improvements be made at the monument before irreparable damage occurred. [15] Despite the public concern expressed on behalf of sites such as Montezuma Castle, the GLO did not provide funds for the upkeep of the national monuments under its care. This situation reflected the difficulties of the divided jurisdiction of the monuments and Congress's failure to allocate money specifically marked for the administration of the monuments. Since 1906, the GLO annually petitioned for appropriations to cover expenses at the monuments for small repairs and to employ local custodians at nominal salaries. These requests, however, had never been approved in appropriation bills, and the GLO opted not to use money from its Protection of Public Lands fund for these purposes. [16] Thus, the Antiquities Act charged the GLO with responsibility for the national monuments under its jurisdiction without providing the agency with the resources to care for them effectively. The lack of congressional appropriations and the limited GLO budget meant that national monuments such as Montezuma Castle continued to suffer from official neglect. [17] In contrast to previous accounts of severe vandalism and damage done to Montezuma Castle, GLO mineral inspector L. A. Gillett reported in September 1915 that the ruins remained in the same state of preservation as he had observed during his last visit in 1898. He noted that visitors had caused little harm to the ruins beyond inscribing their names on the walls and made no recommendation for repairs to the structure. Gillett indicated, however, that the ladders providing access to the Castle were in poor condition and threatened visitors' safety. He further remarked that high waters from Beaver Creek had damaged the foot trail from the wagon road to the base of the cliff and that the road to the Castle from the state highway was very rough. To better accommodate visitors and ensure their safety, Gillett recommended that improvements be made on the ladders, trail, and entrance road. In his opinion, the ruins themselves were not in jeopardy of damage and needed little attention. Concerning the management of the monument, Gillett reported that William B. Back acted as custodian of Montezuma Castle and visited the site nearly every week. Back had left his family home in Missouri and settled in the Verde Valley, where in 1888 he acquired the Montezuma Well property from Link Smith for two horses. Back's homestead entry was patented in 1907, and a few years later he began charging visitors fifty cents for tours of the magnificent natural wonder and the surrounding prehistoric dwellings. Back was personally familiar with tourism-related issues at archeological sites and lived within the vicinity of Montezuma Castle. He seemed to be the ideal candidate to look after the monument. [18] In Inspector Gillett's opinion, this arrangement appeared to provide adequate protection to the ruins: "That is the only supervision the Monument gets save the inspection by this office each year, and is all that it requires, provided the improvements recommended are made." [19] It is unclear why Inspector Gillett did not call attention in his report to the preservation issues that had so deeply concerned previous visitors to the Castle. Yet even if he had expressed the need for the repair and management of the monument, it seems doubtful that Department of Interior officials would have responded with a course of action. However, although the GLO remained unwilling at this time to take responsibility for the preservation of Montezuma Castle, Forest Service officials seemed eager to bring the site under its administration. After the dangerous condition of the ladders and the disrepair of the Castle ruins came to the attention of Forest Service officials in 1915, a flurry of correspondence circulated on the subject of how to best take care of this endangered national monument. District Forester Arthur C. Ringland suggested that because the Castle had suffered under the control of the apparently disinterested Interior Department, the ruins would receive better protection if the secretary of the interior would authorize Forest Service supervision of the site. Although he commented that "these ruins were not of sufficient importance to warrant the assignment of a custodian specifically for this purpose," Ringland proposed to have a ranger from the nearby Beaver Creek Station periodically visit the ruins, noting that the Forest Service made similar arrangements in the case of the Gran Quivera ruins near the Manzano National Forest. He also recommended that the Department of the Interior allocate two hundred dollars for the installation of new ladders. [20] Madison Grant, a prominent New York lawyer and chairman of the New York Zoological Society, also expressed concern about the condition of Montezuma Castle and suggested to Forest Service officials a very different plan for the protection of the ruins. Until such a time as the responsible government agency could provide the Castle the thorough and adequate protection it needed, he advised that no efforts should be made to make the site more accessible to the public. Grant recommended that the ladders be removed and access to the ruins made as difficult as possible pending the appointment of a custodian to watch over the monument and prevent acts of vandalism and destruction. He contended: "It is far more important that these ruins be preserved intact than that the curiosity of casual visitors be gratified." [21] "The mere setting aside of this area as a National Monument and giving it no protection whatever would be worse than useless," Grant concluded. [22] Convenient access to an unsupervised site only prompted the continued destruction and loss of the monument's unique resources. Grant's proposals generated interest among Forest Service officials, yet Montezuma Castle remained under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office. Officials from the Department of the Interior did not respond favorably to the recommendation to close the ruins to visitors and questioned the reports that the Castle had suffered serious damage. In correspondence with Forester H. S. Graves on the subject of the administration of Montezuma Castle, Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bo Sweeney cited Mineral Inspector L. A. Gillett's report as evidence that little vandalism had taken place at the ruins and suggested that the removal of the ladders at the Castle was thus unnecessary. Sweeney justified the department's level of effort regarding Montezuma Castle by claiming that until Congress made funds available for the protection of the national monuments, it would be impracticable to appoint a custodian and repair the damaged ladders. The subtext of such correspondence revealed the department's defensive attitude regarding the preservation of the national monuments. Officials considered these sites low priorities, yet refused to accept responsibility for the consequences of their policy of neglect. In his correspondence with Forester Graves, Sweeney implied that little harm was caused by the department's minimal supervision of monuments such as Montezuma Castle; however, if the supervision of the ruins appeared inadequate, the blame could be attributed to Congress's refusal to allocate funds for the protection of the monuments. [23] Despite his denial of any shortcomings in the GLO's management of Montezuma Castle, Sweeney consented to District Forester Ringland's suggestion that a forest ranger visit the monument from time to time, "as a measure of additional protection." Following this semiofficial agreement between the Department of the Interior and the Forest Service, Forest Supervisor John D. Guthrie instructed Alston D. Morse, a ranger in charge of the Beaver Creek District, to make trips to the Castle at least once a month and to post warning notices supplied by the GLO in the vicinity of the monument. [24] Thus, at this time, the Forest Service more actively participated in the protection of Montezuma Castle than did the GLO. Continuing to demonstrate this greater interest in the preservation of the Castle, Forest Service officials immediately began taking care of details that would facilitate administration of the monument. Forest Supervisor Guthrie forwarded to Ranger Morse copies of Department of the Interior regulations for the protection of national monuments and assigned him a variety of tasks, which included surveying and marking the monument boundaries, erecting large signs on the nearby roads, and posting notices on the rules and regulations at national monuments. Guthrie expressed his agency's attitude toward its assumption of the administrative duties at Montezuma Castle at this time, instructing Ranger Morse to "Please let it be known that the Forest Service now has charge of the Castle and that it will receive more protection than formerly." [25] Although the GLO maintained official jurisdiction over the monument, the Forest Service assumed responsibility for its protection at the practical level. The condition of the ladders and the insufficient management of the monument continued to worry concerned citizens and Forest Service officials. Grace Sparkes, secretary of the Yavapai County Chamber of Commerce and active promoter of tourism and development throughout the county, brought the issue of the condition of the ladders to the attention of officials from the Forest Service, the Department of the Interior, and Arizona's congressional delegation. The replacement of the damaged ladders proved to be the first of many preservation causes in the Verde Valley that Sparkes championed in her lengthy career. Her attention to the matter lent support to Forest Service attempts to obtain funding from the Department of the Interior to make needed repairs at the monument and generated considerable correspondence, which underlined the urgency of the situation. [26] To improve the safety and security of Montezuma Castle National Monument, District Forester A. C. Ringland recommended the installation of new ladders and the construction of an iron fence across the approach to the Castle to limit visitor access to the ruins. Because the monument was not located within the boundaries of a national forest, however, the Forest Service could not furnish the funds necessary for these improvements. [27] Acting Secretary of Agriculture C. Marvin forwarded Ringland's suggestions to the secretary of the interior and offered the services of the local forest rangers to supervise the construction of the fence and ladders, provided that the Department of the Interior finance the work. He estimated the total expenses would not exceed two hundred dollars and noted that a similar arrangement had been made between the two agencies a few years back at Tumacacori National Monument in southern Arizona. At Tumacacori, the Department of the Interior provided funds for Forest Service employees to construct a high iron fence around the monument boundaries and arranged for a local resident to keep the key to the gate of the fence. [28] Although such a cooperative agreement had been made in the past, assistant to the secretary Stephen T. Mather responded that Congress had never placed at the disposal of the Interior Department any funds for the development or protection of the national monuments. As a result, no money was available for such improvements to Montezuma Castle. Mather noted, however, that in its appropriation requests for fiscal year 1917, the Department of the Interior itemized one hundred dollars for repairs to the walls of the ruins and for new ladders. [29] During the summer of 1916, Forest Service officials, local residents, Arizona's congressional representatives, and even an agent from the GLO expressed their concerns to Interior Department officials about the fate of the monument. This mounting pressure finally influenced the Department of the Interior to request funds specifically marked for improvements at Montezuma Castle. In a report to the commissioner of the GLO on his trip to Montezuma Castle in June 1916, Special Agent W. L. Lewis submitted overwhelming evidence of the GLO's failure to provide adequate protection to the Castle and offered a list of recommendations to improve the situation. Lewis observed serious problems that threatened the convenience, accessibility, and safety of the ruins. Echoing sentiments previously expressed by other concerned individuals, he stressed the need to construct new ladders; to improve the trail to the base of the cliff; to provide a register book for visitors to sign (in place of signing the walls); and to repair the badly damaged walls, ceilings, and floors. The detailed descriptions and photographs in his report emphasized the severe condition of the ruins and the dire need for such improvements (figure 16). Agent Lewis's conviction that the national monuments were set aside as "instruments of education" informed his perspective on the condition of the Castle and his suggestions for improvements. Although he noted the dangers to visitor safety presented by the deteriorating walls, Lewis commented that the structure deserved protection for more fundamental reasons: "Aside from the gross negligence in leaving the walls in this condition, the desire to preserve the monument for its educational and historical features should be sufficient ground for strengthening such walls as exist" (figure 17). Supporting his belief in the educational purpose of the monuments, Lewis also advocated that printed information on the historical features and points of interest at Montezuma Castle be made available so that visitors could derive the maximum benefit from their trip to the monument. [30]

The wave of public outcry on behalf of national monuments such as Montezuma Castle represented the latest in attempts to get the Department of the Interior and the General Land Office to take responsibility for the threatened sites under their jurisdiction. At the time of these outbursts of correspondence, bureaucrats in Washington, D.C., were laying the foundations for a new branch of the Department of the Interior to administer the national parks and monuments. Though the passage of the National Park Service Act on 25 August 1916 established an official system of administration for the protected sites and raised the possibility of funding, the national monuments received little immediate benefit from this action. The vision for the newly created National Park Service (NPS), as developed by Stephen T. Mather and Horace Albright, the top officials in the agency, focused on the promotion and development of the national parks as tourist attractions. The national monuments, which lacked the awe-inspiring scenery and tourist appeal of the national parks, did not have a clearly defined place in the park system and were considered to be second-class sites. [31] During this same summer, however, Congress allocated $3,500 to the Department of the Interior for the administration of the national monuments under its care. Although a meager sumthe total averaged to just $120 for each of the department's twenty-four monumentsthis appropriation marked the first monetary commitment to the protection and improvement of the national monuments. From this fund, Interior Department officials initially earmarked $75 for repairs to the walls of Montezuma Castle and the construction of new ladders. When the allotments to Navajo and Papago Saguaro National Monuments were canceled, officials redirected the excess funds to Montezuma Castle, making $325 available for repairs and improvements. Although this money would not cover all of the work necessary at the monument, it promised to help considerably with problems of visitor safety and the preservation of the ruins. [32] Joseph J. Cotter, the acting superintendent of the National Parks, instructed B. H. Gibbs, chief of the GLO Santa Fe Field Division, to arrange for the work to be done at Montezuma Castle. Citing the inspection report filed by Special Agent Lewis, Cotter recommended the repair and strengthening of the walls and roof of the ruin. He also suggested that a responsible person living in the vicinity of the monument be appointed as custodian for a nominal salary and noted that William B. Back, the owner of Montezuma Well, might consider accepting such an appointment. However, because the GLO did not have personnel to attend solely to the national monuments, the work at Montezuma Castle was not immediately undertaken. [33] The Department of the Interior delayed using the newly allocated funds for improvements to Montezuma Castle National Monument, but correspondence from concerned citizens continued to call the attention of officials of that department to the subject of the protection of the prehistoric ruins. In particular, members of the Washington, D.C.—based American Institute of Architects (AIA) acted as outspoken advocates for the preservation of the cliff dwelling. Letters from several AIA members underlined the vulnerability of the unprotected monument and urged the Interior Department to take immediate action to protect the site before its resources were lost to future acts of vandalism. Horace W. Sellers, the chairman of the AIA Committee on Preservation of Natural Beauties and Historic Monuments of the United States, communicated to the Department of the Interior the observations and suggestions of several members of the organization who had recently visited Montezuma Castle. [34] Of special note, Sellers forwarded to Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane a copy of a letter received from Dr. Harold S. Colton of the Department of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania. Colton, who had a special interest in ancient Native American cultures, spent the summer of 1916 in northern Arizona visiting prehistoric ruins, including Montezuma Castle. [35] He considered the Castle "one of the best preserved and most interesting" ruins in the country. At the same time, Colton observed that frequent visitation and the lack of supervision threatened the preservation of the site. He advised that the responsible authorities reconstruct and stabilize portions of the ruins, and appoint a capable caretaker to prevent vandalism. In addition, he suggested that pending the employment of a permanent custodian of the monument and during the times of his absence, the removal of the lower ladder reaching up to the Castle would provide the most certain protection of the ruins. [36] Despite Colton and Grant's advice, the Department of the Interior opted to accommodate visitors and keep the ruins open to the public. Offering another perspective on this matter, the U.S. assistant attorney wrote to Acting Superintendent Joseph Cotter, requesting the removal of the ladders until the repair and strengthening of the walls and floors of the ruin were completed. In its present condition, he suggested, continued access to the interior of the Castle would make worse the structural damage that had already occurred and place visitors at risk of injury. Beyond contributing to the deterioration of the ruins, the policy of allowing unsupervised access to Montezuma Castle exposed visitors to personal danger and raised the issue of the government's liability. The assistant attorney recommended closing the interior of the Castle to the public and cited the GLO's barricading of the Lewis and Clark Cavern in Montana as a precedent for this action. [37] By 1916, however, the newly established National Park Service had not yet articulated a clear vision of or purpose for the diverse group of national monuments. At sites such as Montezuma Castle, the policy of promoting tourism as a means of building support for the Park Service prevailed. Although Interior Department officials decided to keep the Castle ruins open to visitors at the expense of the preservation of its archeological resources, the influx of correspondence from various parties encouraged the department to expedite the repair work at the monument. By November 1916, GLO officials finally began making arrangements for the authorized improvements to the Castle. In March 1917, Mineral Inspector H. W. MacFarren filed a report on Montezuma Castle in preparation for the repair work to be done. MacFarren noted that the appropriations for the monument had been increased to $425 and estimated the following expenses for repairs and improvements: $60 for the custodian's salary at $5 per month, $75 for new ladders, $25 for the cleaning and repair of the "main part" of the Castle, $100 for the cleaning and repair of the "addition" portion of the Castle, $150 for the construction and improvement of trails, and $15 for incidentals. He provided precise instructions about the procedures, materials, and arrangements for all of the work and explained at length the necessity of each recommended action. MacFarren also offered several ideas to facilitate the administration of the monument. He suggested that the future custodian arrange with the county board of supervisors to improve the roads leading to the Castle, post road and warning signs to direct and inform visitors, furnish a register for visitors to sign, make available some informational literature about the ruins, and mark the boundaries of the monument. [38] A custodian was still needed to look after the monument and oversee the repairs and improvements. When William B. Back would not accept the custodianship, MacFarren contacted Alston D. Morse, a resident of Camp Verde. Morse seemed well qualified to take on the responsibilities of the position. He had served for the previous two years as a ranger at the Coconino National Forest and had been assigned to make inspection trips to Montezuma Castle in December 1915. Morse now lived within two miles of the Castle and recently had retired from the Forest Service. Observing Morse's commitment to the preservation of Montezuma Castle, MacFarren wrote that "he exhibits a heart-felt interest in seeing it protected and that has imbibed that spirit and habit so noticeable among Forest Service employees, of wanting to see places of general public interest and value protected." This statement is telling not only of Morse's personal dedication to protecting public lands, but also of the ethic of stewardship among local Forest Service employees at this time. MacFarren contrasted the administrative capabilities of the two organizations when he observed that "the Forest Service could handle the Castle immeasurably better than the Field Service of the General Land Office, since the natural organization, duties and methods of work of the latter service is particularly unsuited to caring for the Castle." However, because Montezuma Castle remained under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior, the arrangements for the repair and improvements to the monument fell to the GLO and the infant National Park Service. [39] Horace M. Albright, the acting NPS director, offered Morse a contract to undertake work at Montezuma Castle, as specified by MacFarren. Morse agreed to construct and install new ladders, clean and repair the main part of the ruin, clean and repair the "addition," and remove all access to the unstable addition section for an estimated sum of two hundred dollars. Park Service officials decided that the recommended work on trails and roads should wait until the following year. They also stipulated that Morse's appointment as custodian of the Castle would occur after his completion of the contracted work, so that his nominal salary of five dollars per month would come under the 1918 appropriation for the monument. [40] Morse started on the repairs and improvements to the monument during the summer of 1917. By 1 August, he finished construction of all the new ladders and had them securely installed. He continued work during the next several monthscleaning out the ruins, repairing damaged portions of the structure, and scrubbing graffiti that had been chalked on the walls. He also placed a register book inside the Castle, which 435 visitors signed between 1 August and 19 November. [41] Early in 1918, NPS director Stephen T. Mather wrote to Morse to inquire about future improvements that would help the monument to better accommodate the anticipated increase in visitation and to arrange for his appointment as custodian of Montezuma Castle. Morse responded with a note indicating that he could not finish the remaining repair work due to his difficulty in obtaining iron rods for the stabilization of the walls. He also stated that the road and trail leading to the Castle needed considerable work, but indicated that he would be unable to complete these projects because he had been called for service in the war effort and did not know when he would return. [42] For the first time since the establishment of Montezuma Castle National Monument, officials from the Department of the Interior expressed concern about the appointment of a custodian to oversee and protect the monument. Mather wrote to Arizona governor George W. P. Hunt soliciting his recommendation of a responsible local resident to replace the absent Morse. Governor Hunt forwarded the name of O. F. Hicks, a Prescott resident and deputy state game warden; by October 1918, Hicks assumed the duties as custodian of Montezuma Castle. Mather requested that Hicks make an inspection visit to the monument and report on its present condition as well as future improvements that seemed advisable. [43] Hicks commented on the need for further repair work, including better fastening of the ladders to the cliff, the stabilization of the "addition" section of the Castle, and the development of the approach road and trail. At this time, the Park Service entrusted the custodian with full responsibility for the monument. However, Mather quickly lost confidence in Hicks's ability to perform as custodian. Shortly after his first inspection report, NPS officials wrote to Alston Morse's wife to determine when her husband was due to return from military service and whether he would still be willing to serve as the custodian of the monument. [44] It is unclear why the Park Service terminated its relationship with Hicks in favor of an arrangement with Morse. Perhaps the agency acted in response to Hicks's suggestion that he be appointed as custodian of all national parks and monuments in Arizona and New Mexico. [45] At this time, the national monuments played a secondary role in the agency's vision of a tourism-oriented park system. Officials may have decided to find a less-ambitious custodian at Montezuma Castle who could take proper care of this specific monument. Upon his return from the war, Alston Morse indicated to NPS officials that he would be unable to perform additional repairs at Montezuma Castle and recommended Martin L. Jackson of Camp Verde as a capable and willing replacement to undertake the needed work. [46] In the years following Morse's initial improvements in 1917—18, the Park Service made various arrangements to provide protection to the monument, but failed to find a reliable custodian to carry out the required duties. The instability of the supervision at Montezuma Castle during this time meant that decisions concerning the site were made by people with varying degrees of familiarity with and knowledge of the prehistoric ruins. The Castle received inconsistent care and protection, depending on the custodian at the time. Such sporadic administration of the national monuments was owing in large part to NPS policies. By the 1910s however, Frank Pinkley, then custodian of Casa Grande and Tumacacori National Monuments, began to champion the cause of the national monuments with top NPS officials. Pinkley had been closely associated with the Casa Grande ruins since his appointment as custodian there in 1901 and had devoted a countless amount of time and energy to the protection, development, and publicity of this site. His fervent dedication to Casa Grande served as an example for the other custodians who faced similar challenges to the care of the monuments. Pinkley shared with NPS officials his thoughts and ideas about the condition of the national monuments and became involved with the administration at other southwestern sites. [47] During the summer of 1919, the Park Service asked Pinkley to make inspection visits to Petrified Forest and Montezuma Castle National Monuments in connection with proposed improvements at each site. The agency expressed concern about the increased visitation and potential vandalism at Montezuma Castle as a result of the easier access to the ruins via the newly constructed ladders. In his instructions for Pinkley's inspection trip, Acting Director Arno Cammerer indicated that the agency desired to quickly appoint a local custodian at a salary of ten dollars per month as a means of preventing further damage to the now more vulnerable monument. He also remarked that up to four hundred dollars might be available if improvement work at the Castle seemed necessary. Thus, the Park Service charged Pinkley with finding the means to protect and improve Montezuma Castle using only the limited funds it was providing. [48] Pinkley traveled to the Castle in September 1919, and in his report to Acting Director Cammerer, he offered estimates for the work needed at the monument. He also recommended that James Sullivan be appointed as custodian of the monument. Sullivan, the road supervisor of Yavapai County, owned a section of land adjacent to the monument boundary. Sullivan had previously discussed with Morse the possibility of providing labor and materials for road and trail improvements in exchange for the right to put an irrigation ditch and flume across a portion of the monument property. [49] Although Morse never made arrangements for this exchange, Sullivan continued to express his desire to divert water from the monument to irrigate his land. When Frank Pinkley approached him concerning the custodianship of Montezuma Castle in 1919, Sullivan again suggested that some type of arrangement might be made in which he would receive permission to construct and use his irrigation ditch as compensation for his services as custodian. Acting Director Cammerer concluded that the agency could grant Sullivan a permit in exchange for his badly needed services. Cammerer asked Pinkley to ensure that the proposed ditch and flume would not appear to be "conspicuous in the monument landscape," and requested that Pinkley work out the terms of an agreement. Sullivan consented to serve as custodian of the Castle for the minimal salary of twelve dollars per year, which he would transfer to the NPS for the permit to run his ditch over the lower part of the monument. Cammerer approved Sullivan's appointment effective 9 October 1920. In subsequent correspondence to the new custodian, Cammerer emphasized the agency's primary concern with the prevention of vandalism at the ruins and provided an explanation of Sullivan's duties and responsibilities to enforce monument regulations. In addition, he noted that Pinkley had arranged for Martin L. Jackson, a local settler who resided on his family's homestead within a couple of miles of the Castle, to undertake improvements to the upper trail, the lower trail, and the drainage system over the cliff for a sum of $180. [50] In order to authorize the permit for Sullivan's proposed ditch, the NPS requested a plat map indicating the length of the ditch, its relation to the monument, and its general location. After reviewing a blueprint Sullivan had provided, Cammerer began to reconsider his decision to allow the ditch and flume to run across monument property. He noted the sizable portion of the monument grounds through which the waterway would travel and expressed concern that it would be conspicuous from different vantage points. Frank Pinkley insisted that the irrigation works, if properly built, would not interfere with the scenic views of the Castle. He also suggested that breaking the agreement with Sullivan would badly hurt the monument's relationship with the local community. [51] However, Pinkley then learned that Sullivan spent a considerable amount of time away from Camp Verde and Montezuma Castle. It seems that Mrs. Sullivan had died, leaving her husband to care for their fifteen children, at which time Sullivan had moved with his family to Prescott without notifying the Park Service. The agency responded to this changed situation by revoking his appointment in October 1921. [52] During the brief period when Sullivan served as custodian of Montezuma Castle, Martin Jackson had completed all of the trail and protective work for which he was contracted. He finished construction of the lower trail, which led from the campgrounds to the Castle; the upper trail, which connected between the top of the cliff and the Castle; and the drainage ditch on the cliff above the Castle. In addition, he accomplished some improvement of the two rough roads that provided access to the monument from the nearby highway. Pinkley was extremely impressed by Jackson's initiative in altering the original work plans to better suit the needs of the monument. He was also pleased by Jackson's discovery of the remains of a rock ruin (the Castle A ruins) adjacent to the Castle. [53] At the time of the NPS termination of its contract with Sullivan, Frank Pinkley enthusiastically recommended that Jackson be appointed custodian at a salary of ten dollars per month. Jackson agreed to inspect the ruins at least once each week. Although this arrangement did not provide the same protection as would a resident custodian living on the monument grounds, the limited funds available to the NPS curtailed the administration of the national monuments. Yet as Pinkley emphasized in his report, the monument needed some type of immediate supervision. During his inspection visit in October 1921, he reported that vandals had broken two holes through the wall of a Castle room and dug out large amounts of debris and artifacts. The agency desperately needed a reliable custodian to prevent future acts of vandalism and to repair damage. Pinkley also indicated other necessary repair work, including the erection of road signs to mark the location of the monument, the painting of the Castle ladders, improvements to the monument roads and trails, and repairs to the structure of the Castle itself. He noted that Jackson could be contracted to undertake these various improvements after his appointment as custodian was approved. [54] Pinkley took a special interest in the administration of Montezuma Castle and expressed his willingness to oversee Jackson's supervision of the site, including semiannual trips to the Castle to assist with larger repair projects. NPS officials, who had little time or energy to devote to matters concerning the national monuments, were happy to have Pinkley look after such "second-class" sites in the Southwest. Acting Director Arno Cammerer instructed the newly appointed custodian Jackson to report directly to Pinkley. [55] The Park Service recognized Pinkley's dedication to the protection and promotion of southwestern monuments and took advantage of his willingness to serve in this capacity. Cammerer wrote to Pinkley that "I would much prefer to handle these improvement matters through you as our representative, in order to maintain your friendly contact with the custodian at all times." [56] Martin Jackson's appointment as custodian of Montezuma Castle and Frank Pinkley's commitment to oversee the administration of the site marked the beginning of a new era in the protection of the ruins. This arrangement promised to correct the problems of inconsistent supervision of and continued damage to the monument that had occurred since its establishment in 1906. The coming years would see greater efforts to make repairs and improvements at Montezuma Castle as well as plans for renovations and additions to the monument's facilities. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

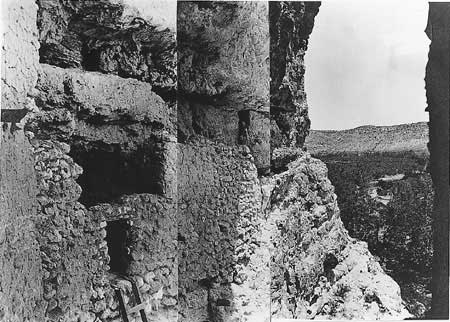

|

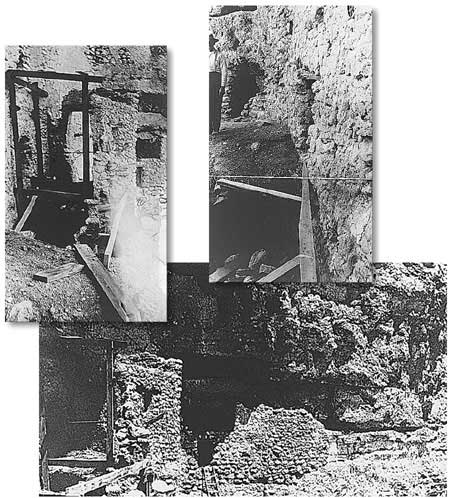

A Past Preserved in Stone: A History of Montezuma Castle National Monument ©2002, Western National Parks Association protas/chap3.htm — 27-Nov-2002 | ||