.gif)

MENU

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

![]() Decade of Expansion

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

State Parks

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

VI. A DECADE OF EXPANSION, 1933 TO 1942 (continued)

EMERGENCY CONSERVATION WORK (continued)

OVERLOOKS, TRUCK TRAILS, AND TRAILS

Another important development of the roads program during the 1930s was the design of overlooks for scenic roads. The development of the Hazel Mountain Overlook in 1935 on the east side of Skyline Drive along the Blue Ridge in Shenandoah National Park illustrated the extent to which naturalistic practices became integrated in the work of the CCC. The overlook was sited along the natural contours of the ridge and was centered on a picturesque outcrop of granodiorite having a dramatic pattern of jointing. Curvilinear stone walls sprang from each side of the outcrop to provide a barrier for cars and a guardrail for visitors. Stone steps built into the outcrop led to the top, where one could view the dark hollows and farmlands below. The parking area was separated from the drive by an island, edged in stone and densely planted with native pines, oaks, and an understory of mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) to screen the sight and noise of traffic on the drive and to blend the overlook with the natural slopes beyond the drive.

|

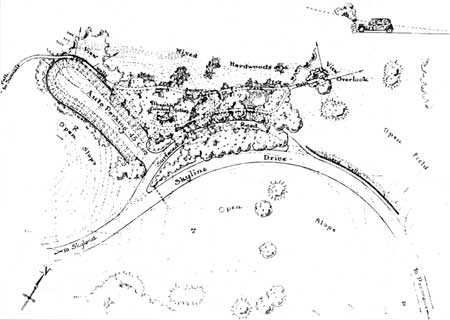

| Jewell Hollow Overlook on Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park was designed by the Eastern Field Office in 1933 and built by the CCC. The site was selected for its valley views, natural outlooks, and interesting rock formations. While the overlook conformed to the natural contours of the hillsides, the parking area was partly built upon a terrace created by a dry-laid and back filled random-rubble wall. CCC-labor and the naturalistic principles of national park design coincided in the 1930s to advance the construction of naturalistic overlooks on park roads and parkways. (National Park Service, Denver Service Center, Technical Information Center) |

The landscape architecture of Shenandoah was characterized by a blending of natural rock and native plants that links it with the romantic gardening tradition espoused by Downing, Parsons, Hubbard, and others. The park's natural outcroppings of rock with their inherent picturesque character were accentuated wherever possible, in picnic areas, at overlooks, along roads and trails, and in developed areas. Artificial assemblages of rockwork were also created, as old stone walls from the period of mountain settlement and farming that preceded the park's establishment were dismantled and the stones scattered. At the picnic grounds at Dickey Ridge, such stones were embedded in the ground and scattered in a random arrangement to build an informal rock garden and to screen and make the comfort stations beyond less conspicuous.

Roadside cleanup was another common activity of CCC camps. This work entailed clearing dead and decaying brush and fallen trees along park roads and removing trees and vegetation that made roads unsafe. This work had begun in Yellowstone in the mid-1920s with donated funds and, by 1930, was covered by appropriated funds as a cost of maintaining and improving roads. Extensive cleanup was undertaken along the Skyline Drive in Shenandoah, where the chestnut blight of the 1920s had left numerous dead stumps and fallen timber. Cleanup also occurred along the Wawona Road in Yosemite and in parks where the white pine blister rust had already taken its toll of native pines.

|

| One important activity of the CCC in Yosemite National Park and elsewhere was the construction of truck roads. These were roads built through the national parks for a variety of administrative and fire control purposes. Although visitors seldom used these roads, care was taken in construction to make them inconspicuous, to protect natural features, to avoid erosion, and to blend them into the natural setting using native vegetation and boulders. (National Archives, Record Group 79) |

Emergency Conservation Work developed many truck trails, the service roads that provided administrative access to various parts of the park often passing through nonpark land. Although these were not traveled by the general public, some park superintendents felt they should receive the same treatment of cleanup and the flattening and rounding of slopes as public roads. Fire trails were six-foot lanes cut through brush and undergrowth generally following ridges, ascending to mountain summits, and penetrating deep forests. These two types of roads together formed the system of fire suppression for a park and as such were an extremely important part of CCC work. Their construction, however, often left scars upon the natural landscape that could be seen from popular viewpoints. Consequently, the roads were situated with concern for landscape protection and screening. They were constructed in ways that would minimize scars and help them blend into the natural scenery. One of Sequoia's resident landscape architects observed that when trails followed wavy lines rather than straight clean-cut ones, they were less conspicuous and blended more readily into the natural setting when viewed from a distance. [41]

Substantial progress was made on the improvement of trails, particularly in popular places. At Yosemite, the cables on Half Dome that had been installed about 1920 by the Sierra Club were now replaced and strengthened by the CCC. This work involved replacing 429 feet of three-eighths-inch cable with seven-eighths-inch galvanized iron cable and thirty-nine pipe posts with stronger one-inch pipe. One section had to be removed every winter so that it was not torn out in the spring by snowslides. Workers drilled forty-one holes, averaging seven inches in depth, by hand in the rock for the new pipe posts. Each man was tied with a piece of rope to the pipe posts while he was drilling to prevent slipping or falling. New wooden steps were installed at the base of each pair of posts, so that hikers could rest at these points. The hemp rope leading to the saddle of Half Dome was retightened and respliced. This trail work was done from a stub camp located at the base of the dome. Although the weather had been perfect before work began, when enrollees set up camp and started the task, it suddenly changed. Every afternoon a storm blew in with either rain, hail, or snow combined with high winds, and work was discontinued. During this time, the men worked on the rehabilitation of nearby Iron Spring. Finishing the trail required forty-one enrollee man-days and five civilian man-days. [42]

|

| Daunted by snow and sleet in May 1934, CCC enrollees from Yosemite's Cascades Camp rebuilt the stairway ascending the eastern face of Half Dome. They replaced the 900-foot cable, refastened iron posts, and repaired wooden treads. While using hammers and chisels to drill new holes, enrollees were held by lifelines tied to the posts above. The slender but strong iron cables and lace-like design enabled the stairway to blend with the gray granite walls of the monolithic dome. (National Park Service Historic Photography Collection) |

Several other cases illustrate the way special kinds of trails were built following the advances worked out by the Engineering and Landscape divisions in the late 1920s. A naturalistic footpath was constructed across the geyser basins at Norris Geyser Basin in Yellowstone in summer 1936. It followed the construction methods that Kenneth McCarter had recommended for the Old Faithful walk in 1929 and took a circular route as indicated on the master plan for the area. It consisted of three stages of construction: the installation of parallel rows of log curbing, the building of a boardwalk of planks supported on two-by-fours, and a final surfacing with concrete and gravel that blended with the natural coloration of the basin. In 1936, the Upper Falls Platform at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone was damaged and the lower platform demolished by falling snow and ice. In keeping with the master plan, the platforms and stairways were rebuilt, and a single new platform was built on the site of the upper platform. The new platform, in the form of a terrace, featured a naturalistic rock guardrail and was accessible by a sturdy log stairway and a log bridge. [43]

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland6b4.htm

![]()