.gif)

MENU

![]() Design Ethic Origins

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

State Parks

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

II. ORIGINS OF A DESIGN ETHIC FOR NATURAL PARKS (continued)

THE AMERICAN PARK MOVEMENT

The transition from the pleasure ground to the public park occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century through the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., Calvert Vaux, and others. These parks were urban and often created through earth moving and extensive planting. Natural features, such as meadows, streams, lakes, waterfalls, and wooded glens, were improved or artificially created to provide picturesque effects. Rustic features and picturesque areas such as the Ramble and Ravine in Central Park would provide miniaturized versions of Montgomery Place's Wilderness.

Downing's principles held that all improvements should be subordinate to and in keeping with natural beauty. The designer's work was to strengthen the inherent expression of beautiful or picturesque natural character. The urban parks of the late nineteenth century were developed with this principle in mind. In 1917, Henry Hubbard recognized the incorporation of the natural landscape, with its landform and vegetation, into naturalistic designs as one of the distinguishing aspects of American landscape design. [30]

FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED, SR.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., developed six principles guiding the landscape design of public parks. These principles pertained to scenery. suitability, sanitation, subordination, separation, and spaciousness. They called for designs that were in keeping with the natural scenery and topography and consisted of passages of scenery" and scenic areas of plantings. The principle of sanitation called for designs that promoted physical and mental health and provided adequate drainage and facilities. All details, natural and artificial, were to be subordinated to character of the overall design. Areas having different uses and character were to be separated from each other, and separate byways were to be developed for different kinds of traffic. Designs were to make an area appear larger than it was by creating bays and headlands of plantings and irregular visual boundaries. [31]

Olmsted's ideas were shaped not only by the writings of Repton, Downing, and others, but also by the example of English parks, particularly Birkenhead Park in Liverpool, which he had visited. He was familiar with the writings and work of Prince H.L.H. von Puckler-Muskau of Germany. whose private park exhibited his own interpretation of the principles of English landscape gardening. Von Puckler-Muskau advocated an approach to park building in which all design was subordinate to a "controlling scheme" and was carried out with simplicity. outwardness, and respect for nature. He had a keen understanding of the relationship between indoor and outdoor space and developed shaded sitting areas at scenic points. Perhaps most significant was the prince's ecological appreciation for native vegetation and his insistence that pleasure grounds should represent nature—nature arranged for the use and comfort of man—and should be true to the character of the country and climate to which they belonged. For this reason, the prince permitted the planting only of trees and shrubs that were native or thoroughly acclimated to the area, avoiding foreign ornamental plants. [32]

By 1858, when Olmsted and Vaux, an architect, submitted their award-winning design for Central Park, Olmsted was also acquainted with the improvements for the Bois de Boulogne in Paris being carried out by Baron Haussmann and his chief engineer, J. C. Adolphe Alphand. These improvements further developed the English gardening idea for public use and enjoyment. Olmsted would meet with Alphand and visit the Parisian park in 1859. [33]

According to Olmsted, the main purpose of a park was to "exact the predominance of nature." Improvements of any type were to be subordinate to the natural character. He wrote,

In all much frequented pleasure-grounds, constructions of various kinds are necessary to the convenience and comfort of those to be benefited; their number and extent being proportioned to the users. If well-adapted to their purpose, strongly and truly built, the artificial character of many of these must be more or less displayed. It is not, then, by the absence nor by the concealment of construction that the natural school is tested. . . . in natural gardening artificial elements are employed adjunctively to design, the essential pleasure-giving character of which is natural. [34]

In 1864, the commissioners of Central Park established a policy for subordinating manmade elements to the natural character of the park landscape. This policy clearly established a precedent for park structures that were inconspicuous and that harmonized with nature. The policy stated,

So far as is consistent with the convenient use of the grounds, vegetation should hold the first place of distinction; it is the work of nature, invulnerable to criticism, accepted by all . . . and affords a limitless field for interesting observation and instruction. . . . Such as finds a place in the Park in answer to the demands of convenience and pleasure should therefore be subordinate to its recognized natural features and in harmony with them, not impertinently thrusting itself into conspicuous notice, but fitly fulfilling the purposes for which it is admitted. [35]

|

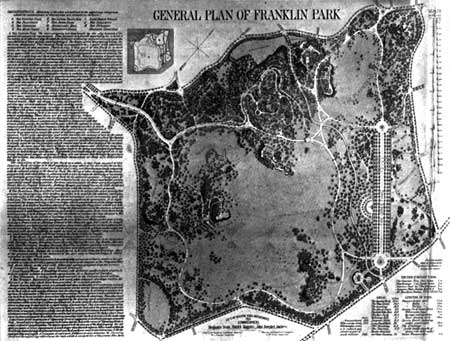

| The 1880s plan for Franklin Park in Boston, Massachusetts, shows Frederick Law Olmsted's concept of a country park, with areas for passive and active recreation and systems of footpaths and carriage roads. While stone walls and boulders were removed from former fields and pastures to create open playing fields and meadows, the park's designers left large areas in the northwest of the park as wilderness. A circuit drive relied upon bridges, curving alignment, and points of interest to immerse carriage traffic in an unraveling panorama of country beauty. Separate paths and stairways led pedestrians to scenic overlooks and picturesque features. (National Park Service, Frederick law Olmsted National Historic Site) |

Buildings should be limited in number, small in scale, and concealed behind groves of trees. Olmsted's design for Central Park had few structures. The old arsenal was temporarily left in place for museum purposes. Olmsted put great effort into making the building less conspicuous by painting it a subdued color, reducing its height, and covering it with vines.

Most of the structures for Central Park were part of the circulation system. Olmsted had laid out a system of independent ways for carriages, horses, and pedestrians. To a substantial extent, the circulation network of curvilinear paths and drives unified the park and guided the visitor through a sequence of predetermined scenes. The system was designed so that one could pass through the park on foot without crossing the carriage roads. Olmsted achieved this by constructing an intricate network of bridges and tunnels, called "arches," that allowed paths and roads to cross over or under each other on separate levels. These passageways also became shelters and were designed to blend into the surrounding scenery. whether earthen banks or rock outcrops. Rocky banks were "worked up boldly against the masonry of the arches" and planted so that visitors were scarcely aware of the structures. The most rustic of these were Olmsted's random masonry arch that fit tightly into the natural bedrock of the Ramble and the Boulder Bridge formed by massive slabs of rock arranged in a bold, exaggerated manner, as if piled up by some great cataclysmic force. These designs, particularly the bridge, used natural materials and blended with the natural setting. In the design of the bridge, Olmsted's naturalism took on exaggerated proportions as the effects of a wild place were not only assimilated but amplified to create highly romantic, picturesque results. These two structures were later illustrated in Samuel Parsons's Art of Landscape Architecture (1915) and, like the designs of other features in Central Park, inspired the work of park designers for decades to come. Calvert Vaux designed many of the lesser structures following Downing's suggestions for constructions of unpeeled tree trunks and twisted branches; these included boathouses, foot bridges, shelters, and benches. [36]

By 1872, the Tweed administration had very different ideas for the park and planned the construction of large museums. Olmsted responded by offering the following criteria for park buildings:

To determine whether any structure on the Park is undesirable, it should be considered first, what part of the necessary accommodation of the public on the Park is met by it, how much of this accommodation could be otherwise or elsewhere provided, and in what degree and whence the structure will be conspicuous after it shall have been toned by weather, and the plantations about and beyond it shall have taken a mature character. [37]

Of Olmsted's greatest parks, Franklin Park in Boston, designed in the 1880s, established the strongest precedent for the design of natural areas. It adapted Downing's ideas about a private pleasure ground to the demands of an urban location, heavy public use, and public management. Envisioned as a "country park" from the start, the park preserved natural wooded areas and picturesque outcrops of Roxbury pudding stone, a local conglomerate. Open meadows were carved out of what had been farms and fields; natural vegetation was retained and enhanced by new plantings, many of which were native to the region; a pond was excavated and planted; overlooks were developed at scenic points; and an expanded repertoire of sturdy park structures and outside furniture was installed to provide for comfort and pleasure. A circuit drive led carriages around the park, up and down natural hills, to stopping places where passengers could climb rustic stone stairways lined with coping boulders to scenic overlooks and picturesque shelters. Henry Hubbard thought highly of Franklin Park, which took form while he was associated with the Olmsted firm. He drew extensively from its example in his Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design (1917) and thereby set it forth as a model for the development of natural areas in the twentieth century.

The roads in Franklin Park were designed to enable visitors to take in the fresh air and enjoy the kinetic experience of viewing the scenery at a relatively slow speed. Because of the limited speed of horse-drawn carriages, the roads could round many tight curves and ascend steep gradients in order to follow the natural topography. In his "Notes on the Plan of Franklin Park," Olmsted wrote,

The roads of the park have been designed less with a purpose of bringing visitors to points of view at which they will enjoy set scenes or landscapes, than to provide for a constant mild enjoyment of simply pleasing rural scenery while in easy movement, and thus by curves and grades avoiding unnecessary violence to nature. [38]

Rockwork was an important unifying feature in the design of Franklin Park. Local stone gathered as old walls were dismantled and former pastures cleared provided construction materials for the buildings, bridges, and other manmade structures in the park and elsewhere in the city's emerging system of parks and parkways. Large, rugged boulders of Roxbury pudding stone were incorporated into the design of many landscape and architectural features. On the open field called the "playstead," Olmsted erected a massive terrace of boulders 600 feet long on which a large two-story Shingle style recreation building was built. The building provided changing rooms for athletes, rest rooms, and, upstairs, a dining room with a large fireplace. A smaller Shingle style shelter in the form of an open-air lookout was built on the summit of Schoolmaster's Hill. The walls of these buildings were constructed of boulders and weathered wooden shingles. The solidity and proportions of their forms conveyed a permanence and sturdiness that was lacking in Downing's constructions of twisted branches. Rockwork provided rustic accents in an overgrown curving stairway of ninety-nine steps and in the edging of overlooks, paths, and roads. A circuit road and system of meandering paths were installed, and grades for strolling and driving were separated by stone bridges and the vine-covered Ellicotdale Arch, a rustic foot tunnel that passed beneath the carriage road. Functional landscape features, such as benches, water fountains, and springs, were characterized by the use of rustic boulders embedded in the soil, laid in courses, or sometimes fashioned into round arches. Water fountains were built from large boulders or slabs of pudding stone, often informally juxtaposed with little or no mortar. Benches were constructed in segments consisting of rough pudding stone piers and horizontal wooden slats forming seats and backrests; segments were fit together to wrap around the curves of the paths they served. [39]

The rockwork at Franklin Park further developed the rustic boulder and split-stone constructions of Central Park. The romantic exaggeration of Central Park's Boulder Bridge gave way to more subdued and less conspicuous forms of rockwork more in keeping with the arch in the Ramble. Overall the features developed for the park in the 1880s and 1890s shared a strong functionalism and greater unity with other similar parts of the park than occurred at Central Park. For the first time, park furniture and conveniences, including benches, water fountains, springs, and shelters, assumed sturdy permanent forms of native rock material.

Franklin Park set a standard for the design of rustic park structures and explored new uses of rockwork and native vegetation. It provided a model for the arrangement of a country park in relation to existing natural features and transportation needs. The Olmsted firm's work at Franklin Park forged a design ethic for natural parks that would be carried into the twentieth century by landscape architects, be adopted and adapted by National Park Service designers, and flourish in the park conservation work of the 1930s in national and state parks.

Several significant developments had occurred in Olmsted's career by the time Franklin Park was being laid out. The firm had been creating the Emerald Necklace, a system of parks and parkways, for the city of Boston and was embroiled in debates over the appropriate design of bridges at various sites. Nationwide, the idea of "wilderness" had taken on monumental dimension through the exploration and geological surveys of the West. Olmsted had become concerned with conservation of natural areas. He had been to the West, working for the Mariposa Mining Company and serving as a commissioner for the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove. Olmsted was also enmeshed in efforts to save Niagara Falls. His continuing involvement at Central Park also enabled Olmsted to test the durability of the park structures over several years and to plan more appropriately for the needs and comforts of visitors to public parks. There is some indication that he found Vaux's unpeeled log pavilions and bridges, built in the spirit of Downing's rustic structures, unable to withstand the use and weathering and, by the end of the 1870s, realized that park structures needed to be sturdier and easier to maintain.

|

| One of many overlooks in Franklin Park in Boston illustrates Frederick Law Olmsted's use of stone steps and coping to create a viewing terrace and an objective for park visitors. (National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site) |

Franklin Park reflected two strong aesthetic influences that had affected Olmsted's work in the 1870s and 1880s. First, he began to collaborate with the architect Henry Hobson Richardson, who was the preeminent practitioner of the Shingle style. Second, he began to work more with wild plants to achieve effects that were highly picturesque and naturalistic.

Olmsted began collaborating with Richardson in the 1870s. Their collaboration resulted in major works such as the Ames Memorial Hall in North Easton, the Niagara Monument in Buffalo, the state capitol in Albany, and many small structures such as gatehouses in city parks and waiting stations on the Boston and Albany Railroad line.

|

| Typical of the sturdy park structures at Franklin Park, this rustic water fountain was made from slabs of local puddingstone laid up in monolithic fashion to imitate the natural rock outcroppings that abounded throughout the park. (National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site) |

One joint project to have substantial influence on the design of park structures was the Boylston Street Bridge, the first major structure that the Olmsted firm designed for the Emerald Necklace. Olmsted desired a bridge that would have a "rustic quality" and be "picturesque" in material, as well as in outline and shadow. He preferred an arch of Roxbury pudding stone or a bridge of rough fieldstones with an arch of cut voussoirs. Richardson sketched a simple arch that fit into the riverbanks and was likely to be built with boulders of local fieldstone. Although much debate ensued among city leaders before the bridge, very different in character from Richardson's single boulder arch, was built, a working relationship had been established between the master park builder and the great architect. Richardson went on to execute designs for several simple gatehouses and water fountains for the Emerald Necklace. [40]

In the early 1880s, Olmsted also collaborated with Richardson on the estate of the Ames family, the town hall, and several other projects in North Easton, Massachusetts. These commissions called for Richardson's bold arches, rusticated stonemasonry, and Shingle style design as well as Olmsted's naturalistic blending of wild plants with existing rugged outcroppings. The gatehouse at the Ames estate, with its bold arch, was a hallmark of Richardsonian design.

The first structures in Franklin Park were three temporary shelters designed by Richardson in 1884 shortly after the park opened. No drawings or photographs of these remain but circumstances indicate that, in Olmsted's opinion, Richardson was capable of designing structures, no matter how small or unpretentious, that were functional, inconspicuous, harmonious with nature, and appropriate to a natural setting. In 1886, Richardson died, ending the fortuitous collaboration. By then the Olmsted firm had absorbed his ideas, which left an enduring legacy to park designers for generations to come. [41]

|

| The benches at Franklin Park in Boston were made of wooden planks and massive piers of Roxbury puddingstone, a local conglomerate. They were designed to follow the flowing curves of the drive and to blend the manmade construction with the surrounding woodlands and rock outcrops. (National Park Service. Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site) |

The Playstead Shelter at Franklin Park was one of the largest park buildings designed by the Olmsted firm. It appears to be Olmsted's design and clearly reflects Richardson's influence. Designed in 1887, the building was completed in 1889. Olmsted planned a 600-foot boulder terrace, intended as a natural platform for viewing sports, as an integral feature of the park; it was built up of innumerable stones and boulders taken from the stone walls of former farms and from the rock-strewn pastures left by the glaciers and cleared by the park engineers. The shelter's lower walls and foundation were made of boulders and were part of the terrace. The lower story provided dressing and shower facilities for players and could be entered from the field through an arch in the terrace. The main floor, with its central area open to the roof with exposed rafters and flanked by two massive fireplaces, consisted of a soda fountain and eating facilities. Because of its horizontal proportions, its native shingle and stone materials, and its connection to the ground through the boulder terrace, the building blended harmoniously into its site. [42]

Although much debate raged over the construction of the Boylston Street Bridge, Richardson's sketch and Olmsted's thinking certainly influenced the design of two stone masonry bridges at Franklin Park's Scarborough Pond by George F. Shepley. Charles H. Rutan, and Charles A. Coolidge, the successors to Richardson's firm. Here in the setting of a country park, the bridges were constructed of fieldstones carefully placed to appear random, with a simple single arch of voussoir stones cut to size but fit together so that the weathered surfaces were exposed to view. Stone arch bridges were promoted in Repton's writings and commonly found across the English countryside as well as in parks such as Emmonville in France. Olmsted's collaboration with Richardson, however, encouraged Olmsted to explore new possibilities in rustic stonework, the park bridge being one of its most important applications and the one that would be most used in the design of rock-faced concrete bridges for national and state parks in the twentieth century. The debate over whether walls should be of rounded boulders or of cut stone laid in a random fashion led to experiments in park design in the Boston parks and parkways. The Scarborough Pond bridges, the large one with a streamlined curving parapet and the other with a stepped parapet, represent pivotal steps away from the picturesque boulder compositions toward designs of rusticated stone cut and arranged randomly to suit a natural setting. These bridges, particularly the larger one, provided models for the designers of national parks and were featured as appropriate for natural areas by Hubbard in his Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design in 1917.

|

| The development of springs was an important aspect of designing natural parks. Echoing the bold rusticated arches of H.H. Richardson's architecture and the wild gardening of William Robinson, the housing for this spring in Franklin Park was made of weathered puddingstone and planted with climbing vines of native grape. The spring was transformed into a quiet and picturesque grotto that blended with the park's natural setting. (National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site) |

Although the collaboration between Richardson and Olmsted was cut short by Richardson's untimely death, its integration of landscape and architectural concerns would continue to be reflected in the work of the Olmsted firm and in metropolitan park and parkway systems across the country. Above all, Richardson's techniques for using native rock in bold, rusticated arches and masonry walls would be carried on in the development of landscape features such as bridges, tunnels, and shelters. Although many of the structures at Franklin Park were designed by others, they clearly show the profound influence that Richardson had on the work of the Olmsted firm and the design of park structures in general.

The other development to profoundly affect Olmsted's work and ultimately the twentieth-century park designers was the creation of wild gardens, espoused by British master gardener William Robinson in The Wild Garden or the Naturalization and Natural Grouping of Hardy Exotic Plants of 1870. Robinson's ideas on introducing the wild species of many nations into the English garden in the form of wild borders, woodland settings, fern gardens, and water gardens in ponds or along streams met with great popularity in England. Small, wild plants such as vines, ground covers, ferns, climbing vines, and water plants could embellish the pleasure ground, adding to the already existing interest in trees and shrubs for their aesthetic character. Robinson's ideas would be further expanded into treatises on creating English cottage gardens and would find an avid following in the English Arts and Crafts movement and among practitioners such as Gertrude Jekyll and William Morris. [43]

By the 1880s, Robinson's ideas were practiced in America and reflected in the work of the Olmsted firm and others. In 1872, Olmsted encouraged a more naturalistic treatment of vegetation in Central Park to avoid a gardenlike appearance and to enhance the park's picturesque qualities. He recommended that shrubbery and trees be thinned, pruned, and blended to avoid uniformity and that vines, such as clematis and honeysuckle, be planted. He offered extensive advice on the wild planting of the Ramble and sent the gardener an annotated copy of Robinson's Wild Garden, noting that Robinson's ideas coincided with what he had all along intended for the Ramble. Olmsted viewed the Ramble as the place most suitable for a "perfect realization of the wild garden."

He wrote:

The rocks in the upper part of the Ramble are to be made permanently visible from the terrace. Tall trees are to be retained and encouraged in the outer parts; dark evergreens on the nearer parts of the ridges, right and left, with a general gradation of light foliage upon and near Vista Rock. The recently made moss gardens are to be revised and the ground rendered natural by removal of some of the boulders, making larger, plainer surfaces, and by the introduction of more varied and common materials. Evergreen shrubs, ferns, moss, ivy, periwinkle, rock plants and common bulbs (snowdrop, dog tooth violet, crocuses, etc.), are to be largely planted in the Ramble, and while carefully keeping to the landscape character required in the general view from the Terrace, and aiming at a much more natural wild character in the interior views than at present, much greater variety and more interest of detail is to be introduced. [44]

At Franklin Park, wild grapevines clung to the walls of arches, springs, and water fountains built from rustic boulders and split stone. Low-growing plants flanked the sides of curving stone steps and stairways. Climbing vines, wild ground covers, and perennial plants were planted in the interstices of the massive boulder wall beneath the Playstead Shelter. Vegetation draped the Ellicotdale Arch, the arbor on Schoolmaster's Hill, and the many springs and water fountains. The carriage road and footpaths were lined with mixed displays of shrubbery and low-growing plants. The abutments of the Scarborough Pond bridges were planted in a rich display of shrubbery.

Robinson's ideas were assimilated into American landscape gardening in the 1880s and 1890s. Articles on the embellishment of dwellings with wild vegetation appeared in Garden and Forest. These included "How to Mask the Foundations of A Country House" in 1889 and "Architecture and Vines" in 1894. The driving force behind an almost excessive use of vegetation to adorn and to hide architecture was, on the one hand, romantic nostalgia for overgrown ruins and, on the other hand, an aesthetic belief that structures, although necessary. distracted from the scenic beauty of a country or natural place and were to be concealed by natural means wherever possible.

The profuse and dense vegetation that resulted from Robinson's techniques in the nineteenth century became less fashionable in the twentieth century. His ideas, however, continued to attract followers into the twentieth century. when they took the form of wild gardens filling remote and often naturally wooded ravines of estates during the "country place era" from the early 1890s through the 1920s. These gardens included work by Hubbard, James Greenleaf, the Olmsteds, Warren Manning, Ferruccio Vitale, and Beatrix Farrand, practitioners who were also involved with the design of national parks. The practice of using wild plants, shrubs, and trees to conceal construction scars, to blend manmade structures with natural vegetation, and to screen undesirable objects from view would continue into the twentieth century and serve the National Park Service's program of landscape naturalization decades later.

Another important development of the nineteenth-century park movement was the creation of regional park systems that included large reservations and scenic natural features. In 1872, park designer H. W. S. Cleveland called for a system of metropolitan parks for Minneapolis that would include the nearby river bluffs along the Mississippi and the land encompassing the nearby lakes, hills, and valleys as well as suitable park areas within the city limits. [45]

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland2b.htm

![]()