|

Lake Roosevelt

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 7:

Building and Maintaining the Park: Administrative and Visitor Facilities (continued)

Employee Housing

Housing for LARO employees was first provided in the town that is now known as Coulee Dam. This community was constructed in the 1930s as Mason City, headquarters for the Grand Coulee Dam contractors. Residences, barracks, businesses, a high school, and dining halls were built almost immediately. Across the river was Engineers Town, a showplace government town for Reclamation engineers that is now the western section of Coulee Dam. From the start, Mason City was heated only by electricity. When the dam was completed and the contractors moved out, Reclamation took over Mason City. [5]

In the 1940s, when only a handful of Park Service personnel worked out of Coulee Dam, Reclamation used a point/drawing system to allot housing in Coulee Dam, based on seniority, size of family, rank, years of service, and other factors. But Frank Banks of Reclamation did manage to save a "choice" residence for Claude Greider, the Park Service Recreation Planner assigned to live at Coulee Dam in 1941. According to the 1942 Reclamation/Park Service agreement, however, other Park Service employees had to "take their chances" through the point system for their living quarters. In other words, they were given no assurance of being able to obtain government housing. By 1948, Greider was complaining that the houses provided in Coulee Dam by Reclamation were inadequate, and he included proposals for eight residences and five apartments for employee housing in the recreation area's 1948 Master Plan. Reclamation agreed to reserve vacant lots in Coulee Dam for Park Service employee housing. [6]

In 1950, Congress appropriated $48,600 to construct three five-room dwellings in Coulee Dam for Park Service housing, and they were completed that December at 606, 608, and 610 Crest Drive. The occupants paid Reclamation for utilities plus an annual charge for amortization of Reclamation's investment in municipal improvements. Some locals strongly criticized the construction of Park Service housing before recreation sites had been developed. For example, the manager of the Grand Coulee Navigation Company, a LARO concessionaire, commented in 1951, "There is a strong and growing feeling among the people of this area that their tax money is being used to provide salaries and superior living quarters for government employees rather than for development of a recreational area to the benefit of the public." [7]

The town of Mason City (Coulee Dam) declined in population in the early 1950s as Reclamation converted from dam construction to long-term operation and maintenance. In 1953, a study recommended that the 450 federally owned temporary houses and the shopping center be sold to the residents. Congress authorized the conversion from government town to self-governing community in 1957, and the sale was essentially completed the following year. The Park Service, of course, was concerned that it might lose its three new houses and the use of three Reclamation houses rented by LARO employees. In 1959, Reclamation transferred to the Park Service the three lots with Park Service houses plus two Reclamation houses that were already being used by Park Service employees (425 and 804 Yucca). In addition, four permanent Park Service employees owned their own homes in Coulee Dam. LARO acquired ten town lots for future residences in Coulee Dam in 1960, probably as a no-fee transfer from Reclamation. [8]

| |

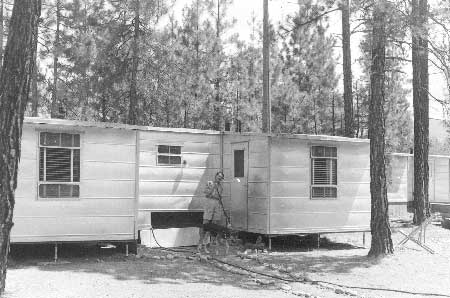

| Transa-house for seasonals at Kettle Falls, 1957. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.HQ.MENG). | |

The challenge of providing housing to employees subject to frequent transfers continued in the 1960s. The volatile housing market in the general Lake Roosevelt region hindered LARO's planning efforts to meet housing needs. The construction work on the third powerhouse during this period led to the removal of nine businesses and fifty-seven residences in Coulee Dam; housing once again grew scarce. The Park Service built three new residences in Coulee Dam in 1966. The three Park Service houses on Crest Drive built in 1950 were located within the Reclamation "taking line" and were scheduled to be moved in 1968. LARO Superintendent Howard Chapman wrote, "I believe we should not be stampeded into moving without a careful appraisal of the situation." In the end, however, the three older houses and one other were moved to new locations in Mason City. LARO turned the three houses built in 1950 plus the one at 804 Yucca over to the Bureau of Indian Affairs between 1983 and 1994. [9]

Outside of Coulee Dam, the housing situation for LARO employees was "most unsatisfactory" in the 1950s, according to LARO's Mission 66 Prospectus. No housing in the Fort Spokane area was available, and there was an acute shortage of housing in Kettle Falls. In 1957, LARO installed three "transa-houses" (small, modular frame houses) at Fort Spokane and one portable building and two transa-houses at Kettle Falls so that seasonal and permanent employees could live close to their work sites. The nationwide trend towards standardized Park Service residences did not affect LARO employee housing until 1962, when two standard Mission 66 residences were built at Fort Spokane. [10]

By 1963, LARO's employee housing situation had improved somewhat to include nine permanent and fifteen temporary quarters. The rates charged the occupants were based on rents charged in Omak, Colville, and Spokane. LARO administration continued to work on obtaining more housing for the growing staff. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Columbia Basin Job Corps out of Moses Lake built portable seasonal quarters for LARO employees at all the major campgrounds, replacing some seasonal trailers and the transa-houses. A new seasonal housing area at Fort Spokane was established in 1973. By 1979, employee housing had increased to eight houses at Coulee Dam, five at Fort Spokane, and five at Kettle Falls, plus fourteen trailers at seven sites. In general, maintenance staff was hired locally and did not require housing, and seasonal employees were often unmarried and could live in shared housing. [11]

|

1996 Employee Housing at LARO:

Coulee Dam — 3 permanent houses, 1 seasonal trailer Spring Canyon — 1 seasonal house, 2 seasonal trailers Keller Ferry Campground — 1 seasonal house Fort Spokane — 3 seasonal houses, 2 seasonal trailers, 2 permanent houses Porcupine Bay Campground — 1 seasonal house, 1 seasonal trailer Hunters Campground — 1 seasonal trailer Kettle Falls area — 2 seasonal trailers, 2 permanent houses, 1 seasonal house Evans Campground — 1 seasonal house [12] |

During the 1980s, LARO formalized its planning for employee housing by preparing a Housing Management Plan. Quarters continued to be added and subtracted; for example, two permanent quarters in Coulee Dam were surplused in 1985 as part of a plan to reduce housing at headquarters. In 1986, as the result of an analysis showing that seasonal rents did not even cover the cost of utilities, all rates were recalculated and increased. In 1988, the annual rents ranged from $4,212 for a Fort Spokane house for a permanent employee to $460 for a trailer for a seasonal at Hunters. A 1993 rent appeal by employees living in government housing in the Fort Spokane District resulted in refunds to fourteen LARO employees. The appeal was based on the assertion that rents should be based on those in the nearby Davenport area rather than the Spokane metropolitan area. [13]

Because of the short season and the difficulty in obtaining rental housing locally, LARO felt that providing housing was critical to recruiting seasonal employees. From the end of the Mission 66 program in 1966 until 1988, no significant funding was available for Park Service units to build or rehabilitate employee housing. Starting in 1989, however, the Park Service received funding through a Housing Initiative for major rehabilitation and trailer replacement along with line-item funding for construction of new or replacement housing. LARO established partnerships with the Park Service's Rocky Mountain System Support Office and the Washington, D.C., Office in 1996 to obtain designs for a four-bedroom dormitory and a duplex. By the late 1990s, LARO policy emphasized providing park housing to seasonal workers, and one of the park goals was to remove, replace, or upgrade to good condition employee housing classified as in poor or fair condition. The last trailer at LARO was removed in 1999. [14]

With sixteen houses and eight mobile homes in 1988, LARO staff felt no additional housing was necessary. With the exception of certain employees who had to occupy government housing in order to provide visitor services and to protect government property, all other LARO employees were assigned housing under competitive bidding using a point system based on salary, number of dependents, and years of government service. LARO staff preferred to retain three houses in Coulee Dam while they evaluated the impact of the anticipated rapid expansion of concession operations at Grand Coulee and Keller Ferry. In response to Congressional concerns in the mid-1990s about the Park Service housing program, housing built for permanent employees' use was re-designated for use by seasonal employees as the units were vacated. The park is trying to keep a permanent employee in residence at Fort Spokane grounds to address visitor and resource protection concerns. [15]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

laro/adhi/adhi7a.htm

Last Updated: 22-Apr-2003