Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

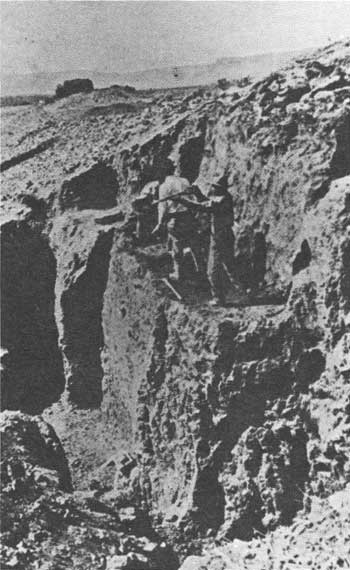

No one at the time quite guessed what the excavation of Pecos would yield. The thirty-year-old Harvard man appointed to direct it, only the sixth archaeologist to earn a Ph.D. in the United States, already had wide experience in the Southwest. He had suggested Pecos. Genial, modest, penetrating, and full of ideas, Alfred Vincent Kidder knew what he was after. Solidly trained in field method by a prominent Egyptologist, he was spoiling to raise New World archaeology above the old antiquarianism that concentrated on the collecting of showy specimens for museums and to move it in the direction "of systematic, planned research and of detailed analysis of data followed by synthesis." Previous excavations in the Southwest had resulted in an array of loose pages. At Pecos, which proved vastly richer and more complex than he had imagined, Kidder found the index. Digging in the dark, loamy soil that had built up and eventually buried the cliff on the east side of the pueblo, in what Kidder called "the greatest rubbish heap and cemetery that had ever been found in the Pueblo region," he uncovered neatly statified deposits containing quantities of broken pottery, pottery that could be classified,

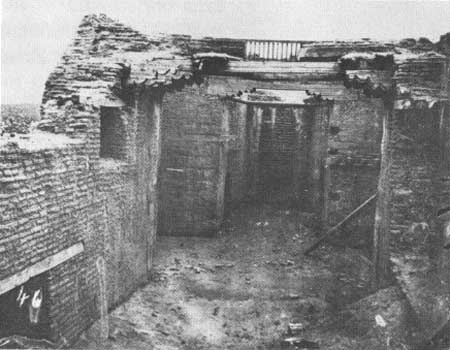

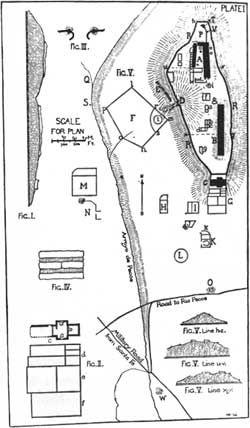

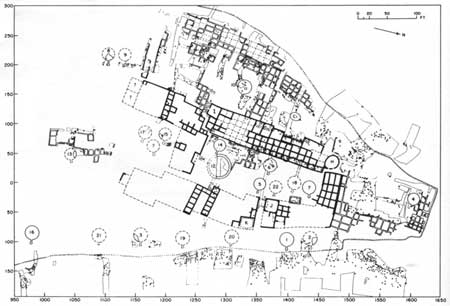

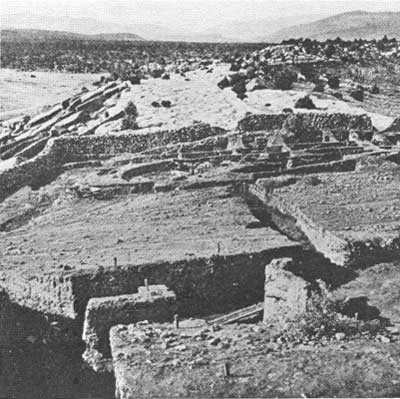

When he got past the middens to the pueblo ruins themselves, Kidder discovered not the large single structure he had anticipated, but another sequence. The historic town of "wretchedly bad masonary" had been laid out on top of the tumbled walls of previous buildings, and the latter over at least two earlier layers of dwellings. This situation thrust him into a study of the "mechanics of pueblo-growth." In the course of ten summers at Pecos between 1915 and 1929, two events broadcast the coming of age of American archaeology. The first was the publication in 1924 of Kidder's An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, with a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos, which has been called "the first detailed synthesis of the archaeology of any part of the New World." The second, in August 1929, was an informal, precedent-setting reunion of Southwestern field researchers at what became known as the "Pecos Conference." Here, at Kidder's invitation, he and his colleagues reached fundamental agreement on cultural sequence in the prehistoric Southwest, definitions of stages in that sequence, and standardization in naming pottery types. When the fiftieth anniversary Pecos Conference convened in 1977, there was high praise for Alfred Vincent Kidder, who in pursuit of his vision made Pecos the most studied and reported upon archaeological site in the United States. Preservation also came. Simultaneous with Kidder's opening field session in 1915, Jesse L. Nusbaum of the Museum of New Mexico had directed the removal of tons of debris from the old church, which, roofless and cruelly weathered, still stood nearly its full height at the transept. His crews then stabilized undercut walls with massive cement footings. In 1920, before Gross, Kelly and Company sold its share of the Pecos Pueblo grant, Harry W. Kelly and Ellis T. Kelly, his wife, along with the company deeded an eighty-acre tract, including mission church and pueblo ruins, to Roman Catholic Archbishop Albert T. Daeger. As agreed, Daeger in turn deeded the historic parcel to the Board of Regents of the Museum of New Mexico and the Board of Managers of the School of American Research in Santa Fe. Created a New Mexico State Monument in 1935 and a National Monument in 1965 (and redesignated as a National Historical Park in 1990), enlarged several times over by a donation of land from Mr. and Mrs. E. E. Fogelson, owners of the Forked Lightning Ranch, Pecos in 1976 is well on the way to becoming what Kidder envisioned in 1916—"an educational monument not to be rivalled in any other part of the Southwest."

This is the day of "environmental statements" and "interpretive concepts" and "master plans," of "resource management" and "visitor use." Under the superintendence of the National Park Service, excavation, research, and stabilization continue. In 1967, when archaeologist Jean M. Pinkley, trenching to find a wall of the eighteenth-century porter's lodge as described by Father Domínguez, hit instead the buried rock foundations of Fray Andrés Juárez' mammoth church, she laid bare a truth that had eluded Bandelier, Hewett, and Kidder. At the same time, she made seventeenth-century pious chronicler Alonso de Benavides, who had portrayed the Pecos church in superlatives, less the liar.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||