Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Plains Apaches and Pecos Even while he oversaw the myriad details of his ministry to the Pecos—slaughtering a sheep, singing the Salve Regina, hoisting a roof beam—Fray Andrés Juárez did not forget the nomads. He had meant what he said in his letter to the viceroy. His mission would become a light unto the Apache nation "so that they want to be baptized and converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith." He could not have forgotten them if he wanted. Every year about harvest time, from late August to October, they showed up to trade, hundreds of them. Some of them wintered nearby, as Pedro de Castañeda phrased it, "under the eaves" of the pueblo. The arrival of these vaqueros—so-called because they followed the vacas de Cíbola, the Cíbola cattle or buffalo— was always an occasion. "I cannot refrain from relating a somewhat incredible though ridiculous thing," recalled Father Benavides as if he had seen it himself,

Overnight, the open grassy valley that spread out to the east and southeast of the church door was transformed into an Apache rendezvous with clusters of conical skin tipis, running children, yapping dogs, and the smoke of a hundred fires. One of Oñate's men who had explored east from Pecos in 1598 left a graphic portrayal of these dog-nomads and their tipis as he saw them on the plains, where he

Items of Trade Trade between Apaches and Pecos had developed in the sixteenth century soon after the nomads adapted themselves to the buffalo plains. From mid-century on, volume picked up, as evidenced by the increasing number of plains artifacts—Alibates flint knives, flint and bone scrapers, and bone hide-painting tools—found at datable levels by archaeologists at Pecos. Because of the near absence of such items in the Tano pueblos to the west, A. V. Kidder concluded that the Pecos "may have been more or less monopolistic middlemen for the westward diffusion" of plains goods. [52] The nomads brought mainly products of the buffalo—hides and leather goods, jerked or powdered meat, and tallow. They also brought tanned skins of other animals, antelope, deer, and elk; flint and bone tools; salt; and on occasion captives of the "Quivira nation," their Caddoan-speaking neighbors to the east. In return, the Pecos gave them maize and other agricultural produce, as well as incidental goods available in the pueblos—painted cotton blankets, pottery, and local turquoise. When harvests were bad and the Pueblos had no surplus to trade, the hungry nomads sometimes fell back on raiding.

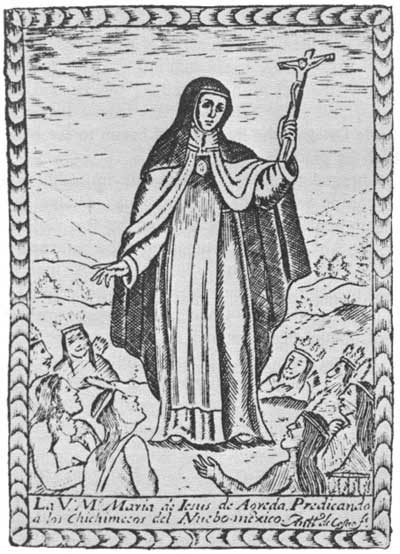

Spaniards Intrude In a land as poor as New Mexico, it is no wonder that the invaders sought to profit from the established Pecos-Apache trade. By 1622, Fray Andrés Juárez recognized that the items packed in by the dog-nomads were "very important both to the natives and to the Spaniards." [53] Both relied on the skins for clothing. In addition, said Benavides, the colonists acquired them "for use as sacks, tents, cuirasses, footwear, and everything else imaginable." To dress a skin, the Plains women scraped the rawhide, rubbed in an oily mixture of fat and brains, dried it, then worked it to make it pliable. Smoking rendered it moisture resistant. On some of the buffalo hides meant for use as winter robes, they left the hair; others they scraped thin and tanned until soft as velvet. Such hides and skins became regular items of tribute exacted from the Pecos by their encomendero. [54] The demands of the Spaniards and the articles they offered for barter—most notably the ubiquitous iron trade knife and later the horse—won a large share of the trade away from the Pecos. Although Coronado found Plains Indian captives living at Pecos as "slaves," the slave trade did not quicken until the Spaniards came to stay. After that, the demand grew so insatiable that Spanish slaving raids directed at the Apaches themselves periodically threatened to wreck the peaceful trade fairs at Pecos and other frontier pueblos. Still, most years they came. When they did, "the friars always talked to them of God." On one occasion, to hear Father Benavides tell it, certain captains of the Vaquero Apaches entered Santa Fe to see for themselves the famous image of the Assumption of Our Lady which the custos had brought to New Mexico. "The first time they saw it was at night, surrounded by many lighted candles, and there was music. It would be a long matter to relate all my conversations with these captains about their learning how to become Christians." The blandishments worked. The Vaqueros agreed to "a large settlement on a site chosen by them." Just then the devil interfered. [55] Eager to profit in the slave trade, a successor of the infamous Juan de Eulate, almost certainly don Felipe de Sotelo Osorio, sent out a strong party of Indians to collect as many captives as they could. On the plains, they came upon the Vaqueros who had just vowed before the image of Our Lady to become Christians. The eager slavers attacked, killed the chief, and returned with some of the others. Stung by the friars' outcry, the governor reneged and condemned the deed as foul. But the damage had been done. [56] Father Juárez also worked on the Vaqueros. Not content to sit back and wait for their annual visit to Pecos, he ventured out onto the plains himself, apparently in the company of Spanish traders. He was probably with Capt. Alonso Baca in 1634. Baca and party pressed due east "almost three hundred leagues" to the Arkansas River. There "the friendly Indians who accompanied him," Apaches no doubt, refused to let the Spaniards cross over into Caddoan Quivira. [57] A generation later, evidently referring to this 1634 expedition, a defendant before the Inquisition admitted that he had gone out on the plains because he wanted the Apaches to make him a captain "as they had done with Capt. Antonio [Alonso] Baca, Francisco Luján, and Gaspar Pérez, father of the one who confesses, and with a friar of the Order of St. Francis named Fray Andrés Juárez." Pérez, an armorer from Brussels who could make trade knives, reportedly "left a son" among the nomads. As part of the elaborate native ceremonial, the Spaniards were supposed to sleep with Apache maidens. [58] Father Juárez, never at a loss for words, this time may have resorted to sign language in defense of his chastity. Missionary Expansion of Benavides During the triennium of Alonso de Benavides, 1626-1629, the Franciscans had things pretty much their own way. Their old nemesis Juan de Eulate, relieved in December 1625 by Admiral Felipe de Sotelo Osorio, departed the colony the following autumn with the returning supply caravan. He had not changed. Soon after he reached Mexico City, he was arrested by civil authorities on charges that he had transported Indian slaves to New Spain for sale and that he had sequestered several of the wagons to haul merchandise duty free. Fined and made to pay the cost of shipping the slaves back to New Mexico, don Juan went free. In fact, he turned up later as governor of Margarita, an island off the Spanish Main. The enduring Fray Esteban de Perea, given leave at last to report in person to his superiors in Mexico City, rode the same caravan as Eulate, his arch adversary. He clutched a packet of documents, the sworn testimony of more than thirty persons heard by Father Benavides sitting as agent of the Inquisition. Still, he would not have the pleasure of seeing the ex-governor do public penance. Even though the Franciscans and the inquisitors accepted his damning reports with thanks, for some reason the Holy Office chose not to prosecute. For his pains, Fray Esteban was reelected custos of New Mexico. [59] While Perea immersed himself in the business of recruiting thirty more missionaries, the largest contingent ever, and in preparations for the next supply train north, Benavides threw himself into expansion with a vengeance. He had brought a dozen friars himself. He could have used four times as many. Operating in all directions from his residence at Santo Domingo, the hardy prelate carried the gospel himself to the Piros in the Socorro area and to the Tompiros east of there. He utilized well what men he had, both veterans and beginners, thrusting new missions into three Tano and Southern Tiwa pueblos and renewing work at Taos, Picurís, and among the Jémez. He tried also, by pursuing their leaders, to convert the nomads who surrounded the colony "on all sides." Miracles or no miracles, with them he failed. [60] Fray Pedro de Ortega among the Nomads One of the men Custos Benavides relied on for missionary outreach to the nomads was Pedro de Ortega, formerly of Galisteo, Pecos, and Taos. In 1625, after three trying years with the Taos, Fray Pedro had accepted reassignment to Santa Fe as guardian of the convento and teacher of the boys in the capital, both Spanish and Indian. When Benavides arrived, he appointed Ortega notary of the Inquisition, to serve "with all fidelity, legality, and secrecy." At the stately service of welcome and institution of the new prelate, it was Ortega who rose after the gospel and, flanked by Sargento mayor Francisco Gómez holding the standard of the Holy Office and by the chief constable, read "in loud and intelligible voice" the first formal edict of the faith. It was the feast of Saint Paul's Conversion, January 25, 1625. The Inquisition had come to New Mexico. [61] While still at Taos, Father Ortega had heard of an Apache called Quinía "very famous in that country, very belligerent and valiant in war." His people, possibly an an cestral band of the Jicarillas, or perhaps Navajos, ranged the mountains north of Taos both east and west of the Rio Grande. Ortega had tried to convert Captain Quinia. Because the chief was so inclined, claims Benavides, a rival shot him in the chest with an arrow. Ortega and Brother Jerónimo de Pedraza, "a fine surgeon," hastened to Quinia's side and cured him, not with a scalpel but with a religious medal. For what it was worth in gifts and attentions, Quinia had kept in touch with the friars. He had begged Father Benavides for baptism. "To console him," wrote the custos, "I went to his rancherias . . . and planted there the first crosses. In the year 1628, Father fray Pedro de Ortega baptized him and another famous captain called Manases, who lived near his rancheria. At the time of their baptism, remarkable incidents occurred." [62] But Benavides, who had stirred up more demand for missionaries than he could supply, had no one to assign. The following spring, like manna, reinforcements appeared. The Return of Perea Esteban de Perea, custos elect since September 1627, had returned to New Mexico with a flock of twenty-nine friars. One had died en route. At chapter meeting, held on or about Pentecost 1629, he established priorities and made assignments. Most of the Piros and Tompiros, for lack of ministers, still had not been baptized. Perea now allotted six priests and two lay brothers to the task. Two more priests he appointed to the Apaches of Quinia and Manases. "And since it was the first entrada to that bellicose nation of warriors," the new governor don Francisco Manuel de Silva Nieto and a body of armed citizens went along. [63] At one of the Apaches' rancherias, they laid up in a single day "a church of logs, which they hewed; and they plastered these walls on the outside." Franciscans and royal governor, in an exemplary show of cooperation, both dirtied their hands in the work. But no sooner had Silva and the soldiers left than "the devil perverted Captain Quinia." The Indian disavowed his baptism and tried to kill one of the missionaries. Then he and his people moved on. Left alone in the woods, the friars had no choice but to abandon the place. [64] María de Ágreda and the End of Ortega A hundred leagues east of Santa Fe and more, beyond the Vaquero Apaches, lived another plains people called the Jumanos, a people who tattooed or painted their faces. The "miraculous conversion" of these "striped" Indians produced superb grist for Benavides' propaganda mill. One way or another, it killed Fray Pedro de Ortega. Some of the Jumanos on trading visits to the pueblos had developed a special relationship with Fray Juan de Salas of Isleta. Repeatedly they had begged him to return with them and baptize their people. Repeatedly he put them off. Then suddenly, with the arrival of the 1629 caravan, there was an abundance of missionaries, as well as a compelling reason to convert the Jumanos. At chapter, Custos Perea had read a letter from the archbishop of Mexico concerning the remarkable case of a Spanish conceptionist Franciscan nun called María de Jesús of Ágreda. Beginning in about 1620, God had miraculously transported her to New Mexico time and again to preach His word to the neglected heathens. The archbishop wanted the friars of New Mexico to investigate the claims "so that they may be verified in legal form." Was it not extraordinary, asked Benavides, that the Jumanos came so regularly every summer begging for baptism? It was as if some person had instilled in them this craving. When questioned that summer, the Jumanos pointed to a portrait of a nun.

What more could an apostle ask? Fray Juan de Salas and a companion joined the Jumanos on their return to the plains. After they had traveled more than a hundred leagues, exulted Benavides, a multitude "came out to receive them in procession, carrying a large cross and garlands of flowers." The nun, they said, had shown them how to process and had helped them decorate the cross. So many clamored for baptism that the two friars decided to go back and enlist help. As they prepared to take their leave they blessed the sick, more than two hundred, who "immediately arose, well and healed." [65]

At the same time, it would seem, another apostolic pair and their native interpreters were following a more northerly path that brought them "within view of the kingdom of Quivira." Despite "great dangers and sufferings," they preached and planted crosses at every turn. Then they too headed back to report all they had seen. This party was led by Pecos veteran Fray Pedro de Ortega, who by now had begun to see himself as an apostle of the plains. [66] Ortega begged to go again. Probably in 1632, probably with Fray Juan de Salas—the accounts vary—Ortega went out to the Jumano settlements, probably on the Río Colorado of present Texas. Although his companion soon returned to the Rio Grande, Fray Pedro stuck it out for six months. He worked hard preaching and catechizing, and he suffered much. According to Benavides' 1634 Memorial, Ortega worked himself to death among heathens and therefore deserved the title of martyr. Writing elsewhere, the same author made the missionary's death among the Jumanos a more conventional martyrdom: "on account of the great zeal of this conversion and because of the suspicion of those idolatrous Indians, they poisoned him with the most cruel poison." [67] Whether of fatigue or poison, Fray Pedro de Ortega, who had broken up idols at Pecos and had courted Quinía's Apaches, was dead. Except for the exaggerated propaganda of Benavides, so too were missions for the nomads, at least for the time being.

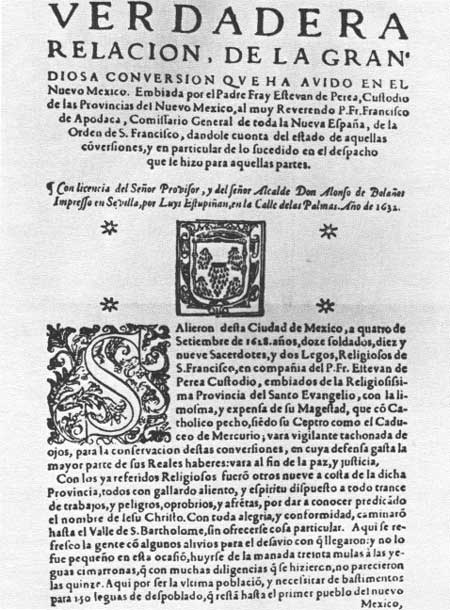

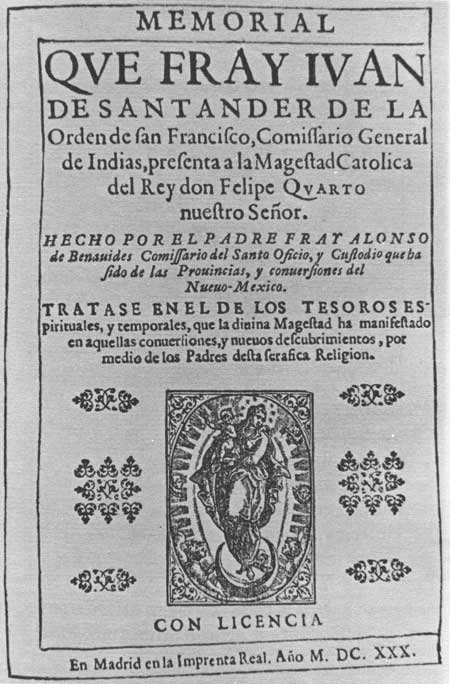

Missionaries to Ácoma, Zuñi, and Hopi In the summer of 1629, Custos Esteban de Perea led a missionary assault on the western pueblos. With Governor Silva, soldiers, ten wagons, and a large remuda, the prelate and eight or ten religious set out for Ácoma on the eve of St. John's Day. One dauntless missionary stayed atop the rock. At Hawikuh, three more chose to abide with the Zuñis, After the first Mass, the ritual act of possession in the name of pope and king, the salvo of arquebuses, the tilting, and the caracoling, governor and custos headed back to Santa Fe while another three friars, with an escort of a dozen soldiers, girded up their loins and pressed on to the Hopis. Meanwhile, Fray Alonso de Benavides, who remained in New Mexico awaiting the southbound caravan, kept himself busy founding a mission at Santa Clara, his tenth by his own count. Because Custos Perea's commission as agent of the Holy Office had not yet arrived, Benavides continued in that capacity. The Tewas of Santa Clara obliged him by painting the Inquisition's coat of arms in the new church, because "they did not wish any other church to have it." [68] Benavides as Lobbyist When finally he did take his leave in the fall of 1629, Benavides vowed he would return. He never did. Ironically, his influence on the missions of New Mexico increased after his departure. He became a lobbyist. Dispatched by his superiors to the court of Philip IV, the amiable and aspiring religious took to the assignment with gusto. Amid the perfume and lace, the lavish display and the notables of the realm, certain of whom had already sat for the gifted young court painter Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez, Fray Alonso inhaled the greatness of Spain. Surely His Most Catholic Majesty, once he was informed of New Mexico's "treasures" and of the "many marvels and miracles" that had illuminated the Franciscans' apostolate in that distant land, surely he would want to increase his support. Why should New Mexico not be created a diocese of the church? And why should he, Alonso de Benavides, not be consecrated its first bishop? His Memorial of 1630, printed at Madrid by royal authority, took the court by storm. The king read it. The council read it. "They liked it so well," wrote Benavides to the friars in New Mexico, "that not only did they read it many times and learn it by heart, but they have repeatedly asked me for other copies." Benavides Meets María de Ágreda In the spring of 1631, Fray Alonso traveled north from the Spanish court for an interview with the Reverend Mother María de Jesús, abbess of the convento of La Purísima Concepción in Ágreda. He carried an order from the Franciscan Father General constraining the nun to tell him everything she knew about New Mexico. Prodded by her confessor and the Father Provincial, she did. In answer to Benavides' leading questions, she gave detailed descriptions of some of the New Mexico friars she had seen on her "flights," including Father Ortega. So many features of the countryside did she recall, even some Benavides had forgotten, that, in his words, "she brought them back to my mind." In his mind, the enraptured friar embellished everything the young abbess said. He begged her to write a letter in her own hand proclaiming God's special concern for the Franciscan missionaries of New Mexico. It made grand publicity. [69]

| ||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||