|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1393

The Geologic Story of Arches National Park |

EARLY HISTORY

Prehistoric People

THE CANYON LANDS in and south of Arches were inhabited by cliff dwellers centuries before the first visits of the Spaniards and fur trappers. Projectile points and other artifacts found in the nearby La Sal and Abajo Mountains indicate occupation by aborigines during the period from about 3000-2000 B.C. to about A.D. 1 (Hunt, Alice, 1956). The Fremont people occupied the area around A.D. 850 or 900, and the Pueblo or Anasazi people from about A.D. 1075 to their departure in the late 12th century (Jennings, 1970). Most of the evidence for these early occupations has been found in and south of Canyonlands National Park (Lohman, 1974), but some traces of these and possibly earlier cultures have been found also within Arches National Park.

Ross A. Maxwell (National Park Service, written commun., 1941) investigated two caves in the Entrada Sandstone in the upper reaches of Salt Wash that contain Anasazi ruins. He mentioned that perhaps a dozen or more other caves should be checked for evidence of former occupation and, also, that he found several ancient campsites littered with flint chips and broken tools.

One cave Maxwell explored some 5 miles north of Wolfe Ranch and north of the park is about 300 feet long and 100 to 150 feet deep. It contains the remains of one or more ruins of a structure he thought may have covered much of the floor. The remaining parts of walls now are only two to four tiers of stones in height, although originally they may have been more than one story high. Maxwell explored a second cave on the east side of Salt Wash, about 2 miles north of Wolfe Ranch, which contains 16 storage cists of adobe.

The faces of many older sandstone cliffs or ledges are darkened by desert varnish—a natural pigment of iron and manganese oxides. The prehistoric inhabitants of the Plateau learned that effective and enduring designs, called petroglyphs, could be created simply by chiseling or pecking through the thin dark layer to reveal the buff or tan sandstone beneath. Most petroglyphs were created by the Anasazi, but those showing men mounted on horses were done by Ute tribesmen after the Spaniards brought in horses in the 1500's. The Fremont people and some earlier people painted figures on rock faces, called pictographs, and some of these had pecked outlines.

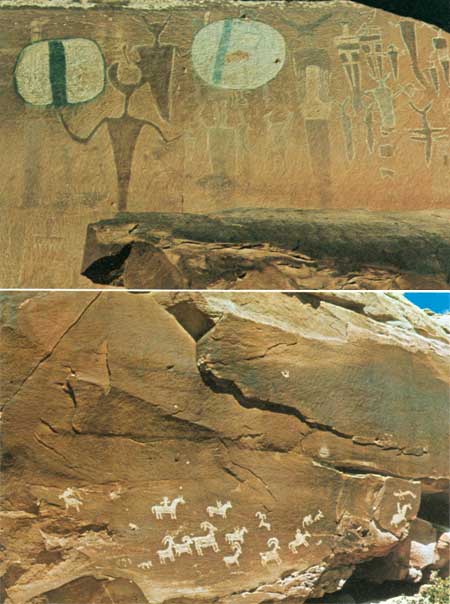

The so-called "Moab panel" was described by Beckwith (1934, p. 177) as a petroglyph, but, as pointed out by Schaafsma (1971, p. 72, 73), it comprises figures having pecked outlines and painted bodies, which actually are combinations of petroglyphs and pictographs. This beautifully preserved group of paintings is shown in the upper photograph of figure 2. Mrs. Schaafsma goes on to say, concerning the "Moab panel":

The long tapered body, the antenna like headdresses, and the staring eyes are characteristic features of Barrier Canyon style figures elsewhere ***. Of special interest here are the large shields held by certain figures. A visit to this site indicated that the shields, although apparently of some antiquity, have been superimposed over some of the Barrier Canyon figures. Whether or not this was done by the Barrier Canyon style artists themselves or later comers to the site is impossible to tell.

|

| ROCK ART IN ARCHES NATIONAL PARK. A (top), "Moab panel," on cliff of Wingate Sandstone above U.S. Highway 163 between Courthouse Wash and Colorado River, believed to be the work of "Barrier Canyon" style people. B (bottom), Petroglyphs on ledge of sandstone in Morrison Formation on east side of Salt Wash just north of Wolfe Ranch, believed to have been cut by Ute tribesmen. (Fig. 2) |

Although definite proof seems lacking, she suggested (written commun., Nov. 3, 1973) that the "'Barrier Canyon style'3 * * * is earlier than the work in the same region clearly attributable to the Fremont." Note the three bullet holes in and near the right-hand shield. A ledge above the panel that contained petroglyphs during her earlier visit had fallen to the base of the cliff by the time my wife and I inspected the panel in September 1973.

3Barrier Creek flows through Horseshoe Canyon in the detached unit of Canyonlands National Park. The canyon walls are adorned by striking pictographs (Lohman. 1974, fig. 2). "Barrier Canyon style" is named after the pictographs found in Horseshoe Canyon.

Mrs. Schaafsma believes the petroglyphs in the lower photograph of figure 2 to be the work of Ute tribesmen, not only because of the horses, but also because of the stiff-legged appearance of the mountain sheep. Note the bullet hole above the panel.

Late Arrivals

Later arrivals in and near Arches National Park included first Spanish explorers, then trappers, cattlemen, cattle rustlers and horse thieves, followed in the present century by oil drillers, uranium hunters, jeepsters, and tourists. Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and other members of The Wild Bunch are known to have frequented parts of what is now Canyonlands National Park (Baker, Pearl, 1971), but it is not certain whether or not any of them traversed what is now Arches National Park.

The first settler in what is now Arches National Park was a Civil War veteran named John Wesley Wolfe, who was discharged from the Union Army about 3 weeks before the Battle of Bull Run because he suffered from varicose veins. In 1888 his doctor told him he had to leave Ohio for a dryer climate or he would not live 6 months, so he took his son Fred west and settled on a tract of 150 acres along the west bank of Salt Wash, where his "Wolfe cabin" still stands (figs. 1, 3). From family letters and newspaper clippings compiled by Mrs. Maxine Newell and other members of the National Park Service (Maxine Newell, written commun., 1971), we learn what life in the area was like:

We have started a cattle spread on a desert homestead. We call it the Bar—DX [

] Ranch. Fred and I live in a little log house on the bank of a creek that is sometimes dry, sometimes flooded from bank to bank with roaring muddy water. We are surrounded with rocks—gigantic red rock formations, massive arches and weird figures, the like of which youve [sic] never seen. The desert is a hostile, demanding country, hot in summer, cold in winter. The Bar—DX Ranch is a day's ride from the nearest store, out of the range of schools.

Although John Wolfe had promised his wife and his other children that he would return home the first fall that his cattle sales netted enough money, he and Fred stayed on and on, and his wife refused to go west and join her husband and son. Eighteen years later he sent money from his pension check to his daughter, Mrs. Flora Stanley, his son-in-law, Ed Stanley, and his two grandchildren, Esther and Ferol, to join him and Fred at the ranch. Their train was met at Thompson Springs (now Thompson), Utah (fig. 7), by John Wolfe for the 30-mile ride to the ranch by horse and wagon. Sight of the tiny log cabin with only a dirt floor brought tears to his daughter's eyes, but her spirits rose considerably after John Wolfe promised to build a new log cabin with a wooden floor. But the children were enchanted with this strange country, with the building of the new cabin, and, especially, with getting to go rabbit hunting with Grandpa Wolfe. The Stanleys stayed at the ranch until Esther was 10, then moved to Moab to await the arrival of their third child, Volna.

In 1910 John Wolfe sold the Bar—DX Ranch, and the entire family moved to Kansas. John Wolfe later moved back to Ohio, and died at Etna, Licking County, on October 22, 1913, at the age of 84, 25 years after his doctor had warned him to move to a dryer climate or face an early death.

Wolfe had sold his spread to Tommy Larson, who later sold it to J. Marv Turnbow and his partners, Lester Walker and Stib Beeson. The old log cabin gradually came to be known as the "Turnbow cabin," and this name appeared on early maps of the area by the U.S. Geological Survey and on early pamphlets by the National Park Service, partly because Marv Turnbow served as a camphand in 1927 assisting in the first detailed geologic mapping of the area (Dane, 1935, p. 4). In 1947 the ranch was sold to Emmett Elizondo, who later sold it to the Government for inclusion in what was then the monument.

From information supplied by Wolfe's granddaughter, Mrs. Esther Stanley Rison, and his great-granddaughter, Mrs. Hazel Wolfe Hastler, who visited the cabin in July 1970, the original name Wolfe cabin, or Wolfe Ranch, has been restored, and appears on the newer maps and pamphlets. (See fig. 1.) What remains of Wolfe's Bar—DX Ranch is shown in figure 3.

|

| WOLFE'S BAR—DX RANCH, on west bank of Salt Wash at start of trail to Delicate Arch. Left to right: Corral, wagon, "new" cabin, and root cellar. "Old" cabin, which formerly was to right of photograph, was washed away by a flood in 1906. (Fig. 3) |

Arches National Park is surrounded by active uranium and vanadium mines and by many test wells for oil, gas, and potash; it is underlain by extensive salt and potash deposits. Oil and gas are produced a few miles to the north and east, and potash is being produced about 12 miles to the south (Lohman, 1974).

Uranium and vanadium have been mined on the Colorado Plateau since 1898 (Dane, 1935, p. 176) and in the Yellow Cat area (also called Thompson's area), just north of the park (fig. 1), since about 1911 (Stokes, 1952, p. 7). The deposits in the Yellow Cat area occur in the Salt Wash Sandstone Member of the Morrison Formation (fig. 4). According to Pete Beroni (U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, oral commun., August 6, 1973), some ore is still being produced in the Yellow Cat area, and the production of vanadium ore will increase as soon as the uranium mill at Moab is converted to also handle vanadium ore. The Corral and so-called Shinarump mines along the southwest side of Moab Canyon just north of Sevenmile Canyon (fig. 1) are still actively producing uranium ore from the Moss Back Member of the Chinle Formation, according to Mr. Beroni.

The occurrences of salt and potash in and near the park and the attempts to find oil and gas nearby are discussed in a recent report (Hite and Lohman, 1973), and the deposits beneath Moab, Salt, and Cache Valleys are discussed in later chapters.

In 1955 and 1956 the Pacific Northwest Pipeline, known also as the "Scenic Inch," was constructed by the Pacific Northwest Pipeline Corp. to transmit natural gas from wells in the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico for a total of 1,487 miles to the Pacific Northwest, with additional pickups from gas fields in northeastern Utah, northwestern Colorado, and southwestern Wyoming (Walters, 1956). This 26-inch pipeline follows the general route of U.S. Highway 163 from Cortez, Colo., past Moab to Sevenmile Canyon 10 miles northwest of Moab, where it turns abruptly to the northeast and crosses about the middle of Arches National Park. It crosses the park road and the flat area between the Fiery Furnace and the southeast end of Devils Garden, but the scars are so well healed that most visitors are unaware of its existence unless they happen to look southwestward across Salt Valley, where the filled excavation is still visible. The filled trench also appears in the lower middle of figure 23.

Unlike Canyonlands National Park a few miles to the south, Arches was not on the route of the famous early-day river expeditions of John Wesley Powell or of most of those that followed; however, the southeastern boundary of the park is the Colorado River, formerly the Grand, which was traversed by the first leg of the ill-fated Brown-Stanton expedition (Dellenbaugh, 1902, p. 343-369; Lohman, 1974).

The canyon of the Colorado River along the southeastern park boundary is deep and beautiful and is a favorite stretch of quiet water for boaters and floaters. Partly paved State Highway 128 on the east bank is a part of a most scenic drive from Moab to Cisco—a small railroad town about 32 miles northeast of the eastern border of figure 1 (fig. 7). This road has been variously called the "Moab Mail Road," the "Cisco Cutoff," the "Dewey Road," or the "Dewey Bridge Road" after an old suspension bridge (fig. 7) across the Colorado River at the old townsite of Dewey about 12 miles south of Cisco. During the summer this deep colorful canyon may be viewed at night by artificial illumination. Each evening one-half hour after sundown, an 80-passenger jet boat leaves a dock north of the highway bridge, carries passengers several miles up stream, then floats slowly downstream followed by a truck on the highway carrying 40,000 watts of searchlights which play back and forth on the colorful red canyon walls, while the passengers listen to a taped discourse. The entire trip requires about 2 hours.

The spectacular arches and red rocks of Arches and vicinity have been used to advantage in making color movies and color TV shows. Parts of the recent Walt Disney film "Run, Cougar, Run" were filmed beneath Delicate Arch (fig. 43), in Professor Valley of the Colorado River just east of the park (fig. 7), and in other sections of the canyon country.

Ever since military jet aircraft broke the sound barrier, there has been a growing number of protests from concerned citizens, organizations, and National Park Service officials concerning the dangers sonic booms have posed to Indian ruins and delicate erosional forms in our national parks and monuments, such as natural bridges, arches and windows, balanced rocks, and natural spires or towers. Many instances of damaged ruins, roads, erosional forms, and broken windows were reported. My wife and I can vouch for the destructive power of such booms, for in October 1969, while we were having breakfast at Squaw Flat Campground in The Needles section of Canyonlands National Park, a particularly severe blast from a low-flying jet not only violently rocked our jack-supported trailer but broke the windshield of our car.

At Arches National Park, particular fear was felt for Landscape Arch (fig. 53), thought to be the longest natural stone arch in the world, and many a special round trip from headquarters involving 47 road miles and 2 trail miles was made to check on the condition of this arch after especially loud sonic booms were heard. Finally, in April 1972, following a rash of newspaper and magazine articles that spread across the nation, the Secretary of the Air Force put a virtual stop to this danger by ruling that, except in an emergency (Moab Times-Independent, April 12, 1972):

Supersonic flights must not only avoid passing over national parks, they also may not fly near them, according to the new regulation. For each 1,000 feet of altitude, the pilot must allow one-half mile between the flight path and the park boundary. The regulation also prohibits supersonic flights below 30,000 feet (over land) so the high speed planes must allow 15 miles between the nearest park boundary and the flight path.

Let us hope that with the aid of this long-needed regulation and cooperation from visitors, the arches will remain intact for many more generations to see.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1393/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007