|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1393

The Geologic Story of Arches National Park |

BEGINNING OF A MONUMENT

ACCORDING TO former Superintendent Bates Wilson (1956), Prof. Lawrence M. Gould, of the University of Michigan, was the first to recognize the geologic and scenic values of the Arches area in eastern Utah and to urge its creation as a national monument. Mrs. Faun McConkie Tanner1 told me that Professor Gould, who had done a thesis problem in the nearby La Sal Mountains, was first taken through the area by Marv Turnbow, third owner of Wolfe cabin. (See p. 12.) When Professor Gould went into ecstasy over the beautiful scenery, Turnbow replied, "I didn't know there was anything unusual about it."

1Mrs. Tanner, of Phoenix, Ariz., is the author of an earlier history of Moab (her hometown). She has completed a revision entitled, "The Far Country—A Regional History of Moab and La Sal, Utah," which will he serialized in the Moab Times-Independent, after which it will be published.

|

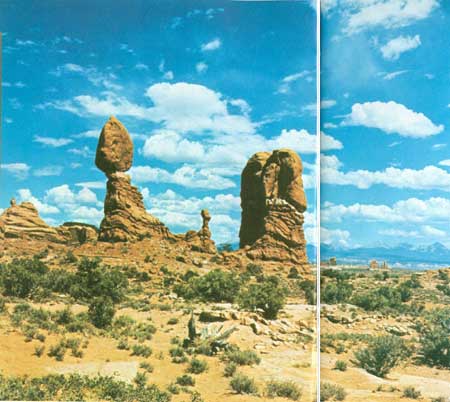

| BALANCED ROCK, guarding The Windows section of Arches National Park. Rock is Slick Rock Member of Entrada Sandstone resting upon crinkly bedded Dewey Bridge Member of the Entrada. White rock in foreground its Navajo Sandstone. La Sal Mountains on right skyline. (Frontispiece) |

Dr. J. W. Williams, generally regarded as father of the monument, and L. L. (Bish) Taylor, of the Moab Times-Independent, were the local leaders in following up on Gould's suggestion and, with the help of the Moab Lions Club, their efforts finally succeeded on April 12, 1929, when President Herbert Hoover proclaimed Arches National Monument, then comprising only 7 square miles.2 It was enlarged to about 53 square miles by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Proclamation of November 25, 1938, and remained at nearly that size, with some boundary adjustments on July 22, 1960, until it was enlarged to about 130 square miles by President Lyndon B. Johnson's Proclamation of January 20, 1969.

2For the benefit of visitors from countries in which the metric system is used, the following conversion factors may be helpful: 1 inch = 2.54 centimeters, 1 foot = 0.305 meter, 1 mile = 1.609 kilometers, 1 U.S. gallon = 0.00379 cubic meter.

According to Breed (1947), Harry Goulding, of Monument Valley, in a specially equipped car, traversed the rugged sand and rocks of the Arches region in the fall of 1936 and, thus, became the first person to drive a car into The Windows section of Arches National Monument. Soon after, a bulldozer followed Harry's tracks and made a passable trail.

When my family and I visited the monument in 1946, the entrance was about 12 miles northwest of Moab on U.S. Highway 163 (then U.S. 160), where Goulding's old tire tracks led eastward past a small sign reading "Arches National Monument 8 miles." This primitive road crossed the sandy, normally dry Courthouse Wash and ended in what is now called The Windows section. At that time there was no water or ranger station, nor were there any picnic tables or other improvements within the monument proper, and the custodian was housed in an old barracks of the Civilian Conservation Corps near what is now the entrance, 5 miles northwest of Moab.

Former Custodian Russell L. Mahan reported (oral commun., May 1973) that soon after our initial visit in 1946 a 500-gallon tank was installed near Double Arch in The Windows section and connected to a drinking fountain and that two picnic tables and a pit toilet were added. At that time the only access to Salt Valley and what is now called Devils Garden was a primitive dirt road which, according to Breed (1947, p. 175), left old U.S. Highway 160 (now U.S. 163) 24 miles northwest of Moab, went 22 miles east, then followed Salt Valley Wash down to Wolfe cabin (fig. 1).

According to Abbey (1971), who served as a seasonal ranger beginning about 1958, a sign had by then been erected at the crossing of Courthouse Wash which read:

WARNING: QUICKSAND

DO NOT CROSS WASH

WHEN WATER IS RUNNING

The ranger station, his home for 6 months of the year, was what Abbey described as "a little tin housetrailer." Nearby was an information display under a "lean-to shelter." He had propane fuel for heat, cooking, and refrigeration, and a small gasoline-engine-driven generator for lights at night. His water came from the 500-gallon tank, which was filled at intervals from a tank truck. At that time there were three small dry campgrounds, each with tables, fireplaces, garbage cans, and pit toilets. By that time an extension of the dirt road led northward to Devils Garden, and some trails had been built and marked.

Bates Wilson became Custodian of the monument in 1949 and later became Superintendent not only of Arches but also of the nearby new Canyonlands National Park (Lohman, 1974) and the more distant Natural Bridges National Monument. In the fall of 1969, Bates told me of some of his early experiences in the undeveloped monument, including the evening when 22 cars were marooned on the wrong (northeast) side of Courthouse Wash after a flash flood. Bates and his "lone" ranger brought ropes, coffee, and what food they could obtain in town after closing time, threw a line across the swollen stream, had a tourist pull a rope across, then took turns wading the stream with one hand on the rope and the other balancing supplies on his shoulder. After a fire had been built and hot coffee and food passed around, the spirits of the stranded group rose considerably, except for one irate woman from the East, who refused to budge from her car. Bates and his helper finally got the last car out about 1 a.m., after the flood had subsided, and Mrs. Wilson then supplied lodging and more food and coffee for those who needed it.

During and for sometime after World War II and the Korean War, lack of maintenance funds and personnel had prevented improvement of the facilities in many of our national parks and monuments, particularly in undeveloped ones like Arches. The day was saved through the wisdom and foresight of former Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth, who saw the need and desirability of putting the whole "want" list into one attractive, marketable package. In the words of Everhart (1972, p. 36):

Selection of a name is of course recognized as the most important decision in any large-scale enterprise, and here Wirth struck pure gold. In 1966 the Park Service would be celebrating its fiftieth anniversary. What a God-given target to shoot for! Why not produce a ten-year program, which would begin in 1956, aimed to bring every park up to standard by 1966—and call it Mission 66?

The ensuing well-documented and cost-estimated plan for Mission 66 was enthusiastically backed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and approved and well supported by Congress to the tune of more than $1 billion during the 10-year period. For Arches, this included a new entrance, Park Headquarters, Visitor Center, a museum boasting a bust of founder Dr. Williams, and modern housing for park personnel, all 5 miles northwest of Moab. By 1958 (Pierson, 1960) a fine new paved road between Park Headquarters and Balanced Rock (frontispiece) was completed. These badly needed improvements were followed by the completion of the paved road all the way to Devils Garden, the building of the modern campground, picnic facilities, and amphitheater in the Devils Garden, and the construction of turnouts and marked trails.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1393/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007