.gif)

MENU

|

Fauna of the National Parks — No. 3

Birds and Mammals of Mount McKinley National Park |

|

Mammals

DESCRIPTIONS OF MAMMAL SPECIES

DALL SHEEP

Ovis dalli dalli [NELSON]

GENERAL APPEARANCE.—The Dall sheep is somewhat smaller than the Rocky Mountain bighorn of the United States. A fair-sized ram of the Dall sheep stands about 39 inches at the shoulders and weighs more than 200 pounds. The older rams have large, much curled horns (frontispiece). Young rams and female sheep have short, slightly curved goatlike horns (fig. 74). The female is about two-thirds the size of the ram. At a distance young rams are difficult to distinguish from the females. The ears of the Dall sheep are short, round, and well covered with hair (fig. 74). The tail is small and inconspicuous, being only about 4 inches long. Total length, 58 inches; tail, 4 inches; hind foot, 16.6 inches.

Figure 74.—Female Dall sheep,

showing short, slightly curved, goatlike horns, and heavy, pure white

winter coat, the ewes are sometimes incorrectly called "ibex."

Photograph taken May 30, 1932, Savage Canyon. W. L. D. No. 2706.

IDENTIFICATION.—Two important diagnostic characters of the Dall sheep are the white color and, in the rams, the relatively slender, wide-spreading horns (fig. 75). Contrasted with the Dall sheep, the Rocky Mountain bighorn of the United States is sandy-brown in color; its horns are large at the base and are closely curled and they do not extend out on either side of the head to so great a distance. Tracks of the Dall sheep show straight-sided-hoof marks which are well separated anteriorly (fig. 76) and are only half as large as are the tracks of caribou.

Figure 75.—Characteristic features

of the male Dall sheep are the relatively slender widespreading horns.

Photograph taken June 1, 1932, Igloo Creek W. L. D. No. 2453.

Figure 76.—Tracks of ewe and lamb

(Ovis dalli). Note straight-sided-hoof-prints and anteriorly spread toes.

Photograph taken June 7, 1926, Savage River. M. V. Z. No. 5205.

DISTRIBUTION.—Dall sheep are found in the mountains of central and northern Alaska and the Yukon Territory. They are numerous throughout the park on the north side of the main Alaska Range. The reason for this is that the snowfall is so heavy on the south side of the range that it would be difficult or impossible for the sheep to exist throughout the winter. Not only would their food be covered, but they would be so hampered in their movements by the heavy snowfall that they would be in grave danger from natural enemies. However, on the north slope the snowfall is relatively light and many ridges are swept bare of snow by the winter winds. This means that on the steep mountain slopes food is available during all seasons of the year and that the sheep are able to move about freely all winter and to thus escape their enemies.

HABITS.— During the entire period of our stay in the region in 1926, there was scarcely any time in the 24 hours each day that it was not possible to look out from our camp and count from 57 to as many as 104 Dall sheep on the surrounding hillsides within a mile of the camp.

In 1932, following the most severe winter in 40 years, I learned that the unusually heavy snowfall had caused many mountain sheep to die, presumably through lack of available food. Both mountain sheep and caribou, because of their disadvantage in deep snow, are said to have been killed by the timber wolves and coyotes. The apparently poor reproduction among the sheep in the spring of 1932 may have been due to the poor physical condition of the ewes.

In the Mount McKinley district the mountain sheep have distinct summer and winter ranges. The chief wintering ground is the north, or outside, range and adjacent foothills. The territory occupied by the sheep in winter varies in elevation from 1,000 to 5,000 feet. This winter range is characterized by a relatively light snowfall, 3 to 4 feet, and by the general ruggedness of the topography. In many cases the mountain slopes are so steep that the snow does not stick. Another reason for this region being favorable winter range for the sheep is the abundant growth of red-top and other grasses, found in sheltered nooks at the bottom of the lower rock-slides and cliffs in the area, often attaining a height of 3 feet during the summer. This grass matures and cures naturally so that a nutritious and accessible food supply is available even during the heaviest storms. The abundance of tracks and other "signs" found about these places and amid the alder thickets indicate that the sheep congregate in considerable numbers at such points during late winter and early spring. The sheep abandon the winter range usually during the first week in June and, crossing the low valleys, move southward to the higher summer pastures in the main Alaska Range. Here they obtain fresh forage throughout the summer following the springing vegetation upward along the snowline. Thus we find a very marked system of deferred grazing practiced by the Dall sheep. Their sojourn in the main Alaska Range during the summer gives the vegetation on the winter range an opportunity to grow and mature. Incidentally, this system assures the sheep an adequate food supply during the stressful time of winter, when the main range is heavily blanketed with snow.

The head of Savage River, above the Caribou Camp, is a favorite summer home of several bands of mountain sheep. This is one of the most accessible and best places for park visitors to see not only mountain sheep but also caribou and even grizzly bears. Divide Mountain, between the Sanctuary and Savage Rivers on the old trail to Copper Mountain, is also an excellent place to find sheep, particularly in late summer (fig. 77). Those visitors who make the trip to the base of Mount McKinley have numerous opportunities to observe the Dall sheep at Sable Mountain, Toklat, and various points en route. However, it was our experience that the opportunity to study sheep was even more favorable at Igloo Creek and Sable Mountain than it was nearer the base of Mount McKinley.

Figure 77.—Male Dall sheep on summer range.

Photograph taken July 22, 1920, Double Mountain. M. V. Z. No. 5171.

We witnessed several migrations of sheep from their winter range to their summer pasture. On June 15, 1926, a typical trek was observed at about 10 o'clock in the morning. We noted a flock of 64 mountain sheep working down from the north range into the valley near the transportation company's main camp on Jenny Creek. The sheep grazed down the hill, keeping in a compact body in the open away from the spruce timber. At a distance they looked like a large moving mass of snow spreading out over the brown tundra. After considerable hesitation the band, led by an old female, made a dash across the willow bottom land to a nearby gravel ridge on the opposite side of the valley. The flock traveled in single file as they went through the willow thickets which dotted the stream bed. Each animal marched along with military precision until their River Jordan had been crossed. Upon reaching elevated hard ground on the other side the flock broke rank and scampered off wildly along the ridge into the foothills of the nearby main Alaska Range. Groups of old rams often linger for several days on the winter range after the ewes and lambs have left.

One reason for the sheep wintering in the more rugged portions of the north range is doubtless because in such places suitable protection is secured for the young lambs at birth. Thus we found that certain south-facing, rugged cliffs in Savage River Canyon were regularly selected as lambing grounds. The presence there of numerous small potholes and caves at the bases of perpendicular or even overhanging cliffs (fig. 78) gave abundant protection to the newly born lambs and to their mothers. Tracks of wolverines and observed attempts of golden eagles to capture the young lambs proved the value of such hiding places, particularly while the lambs were small. As a matter of fact, observations showed us that the young lambs would not normally venture more than 50 or 100 yards from such havens of refuge until they were several weeks old and able to run about and in a large measure to take care of themselves. To many people, a small pothole at the base of a cliff—often filled with broken rock (fig. 79)—would seem a hard cradle indeed, yet it affords safety and protection to the lambs which is so essential to their welfare.

Figure 78.—Lambs of the Dall sheep

are usually born at the base of some secluded cliff such as that shown here.

Photograph taken July 27, 1926, Savage River.

Figure 79.—Slight depressions filled with

broken rocks often serve as cradles for the lambs of the Dall sheep.

Photograph taken June 5, 1926, Savage Canyon. M. V. Z. No. 5204.

The lambs are born from early in May, while there is still considerable snow on the ground, until late in June. In studies made extending over a period of years, considerable seasonal variation has been found in the lambing period. For instance, in 1926, following an early rutting season, the first lamb of the year was noted on May 5 and by the last of May all of that season's lambs had been born. In 1932, following a late breeding season, the first lamb was seen May 31 and some lambs were not born until the last of June. Two pregnant ewes that became stranded in deep snow were captured by rangers and later were taken to the University of Alaska at Fairbanks where they gave birth to normal lambs on the 17th and 18th of May.

On June 28, 1932, Mr. F. W. Morand, while collecting insects high up amid the crags of Cathedral Mountain, heard a low groaning sound and stealing cautiously around a rocky point he found himself within 6 feet of a female mountain sheep which was in labor. Not wishing to frighten the animal he retreated and stole quietly around to the other side of her where he was 20 feet distant and partly concealed. By that time the lamb had been born and the ewe was standing over it and licking her new offspring. The lamb's cradle was a warm pocket in the rock, screened in on both sides and above by protecting cliffs. Delivery of this lamb had taken only about 15 minutes. As a rule each ewe gives birth to but one lamb per season although at times there are twins. The long-legged, wobbly, fuzzy lambs are a never-ending source of interest to park visitors. They are grayer in color than the adults and in the distance appear to be decidedly darker than their mothers, who keep a very watchful eye over their offspring.

It was found that frequently from six to a dozen ewes and their lambs congregated into a sort of nursery, or school, which was always near protected cliffs or rocks. Thus, on May 27, 1926, in the Savage River Canyon, we crawled up to within 200 feet of a hunch of ewes and lambs. At this time the ewes were in poor physical condition. Their white coats were earth-stained from lying on the thawing ground. Near the same locality on June 5, we found what we took to be the same flock. There were 10 lambs in a close little pasture romping about together. They appeared to love to scamper about the rock piles and sheer cliffs. When alarmed, they would all rush at once to the top of a pinnacle rock where they would stand, bunched together. Then, at a signal they would fairly fly down the steepest way only to return and repeat the performance. On numerous occasions we noted that such schools of lambs were always watched over by an old female (fig. 80). There seemed to be some division of labor, since the other mothers seized this opportunity while the youngsters in the nursery were playing under the vigilant eye of their teacher to go off for some considerable distance, in certain cases almost a quarter of a mile, to secure food. The favorite game of the lambs seemed to be follow-the-leader. Each youngster would take his turn at leading the way up the side of a boulder or cliff which seemed unscalable to us. The remaining lambs made every effort to follow in the footsteps of the leader and they usually succeeded. As soon as one circuit had been completed a new leader would start out, choosing a slightly different route. This system of play, which seemed to us to be extremely hazardous, doubtless was nothing but the normal training for young mountain sheep which would enable them to maintain their race and to escape their enemies. Only on one occasion did we see any unusual concern exhibited by the mother for her wayward offspring. In this instance, a lamb ventured out onto a sloping rock which overhung a sheer drop of about 80 feet. We held our breath as we watched the daring youngster, seemingly headed for certain destruction. The watchful lamb's mother had also taken in the situation and suddenly dropping her seeming indifference she bounded quickly over the rocks and deftly butted her erring offspring back to safety.

Figure 80.—One ewe (Ovis dalli)

protected her lamb by standing over it, while the other ewe started to leave.

Photograph taken May 27, 1926, Savage Canyon. M. V. Z. No. 5189.

In one rocky basin of about 20 acres we counted 34 sheep, all being ewes with their small lambs. At this date, May 23, 1926, the lambs were small enough to walk under their mothers' bodies without touching them. One lamb ran in between its mother's front legs and began to nurse, butting the udder just as a domestic calf sometimes does. While this lamb was nursing, another one of the same size which we thought might be one of a pair of twins started to nurse also; the mother turned around and repeatedly butted it aside. It evidently did not belong to her. We found that the young lambs were not particular about seeking out their own mothers. They would attempt to suckle any nursing ewe. However, the latter had decided objections to nursing the offspring of other ewes so that it was not uncommon to see a lamb try two or three times before he succeeded in finding his own maternal font.

On one occasion we watched a baud of 10 ewes and 11 small lambs as they fed together on a small bench in an area not more than 100 feet square. While we watched, a golden eagle circled out around a projecting cliff directly over the sheep. The moment the eagle came into sight there was an immediate scamper. The young lambs disappeared as if by magic, seeking safety in the potholes and overhanging cliffs. Within 5 seconds not one of the lambs was in sight, and a period of 10 minutes passed before they began to reappear. We watched them as they came timidly forth from under the overhanging cliffs. On this occasion we were unable to distinguish any signal of alarm on the part of the adult sheep. The lambs simply scattered in all directions upon catching sight of the eagle. During the summer of 1932 I watched several golden eagle nests containing young, but I never found the bones or other remains of lambs in or below any of the nests. In the same locality in June 1908, Charles Sheldon observed golden eagles swooping at young lambs which were protected from such aerial attacks by the ewes standing over them (fig. 80) and thrusting their horns upward at the swooping eagles. On June 7, 1908, at the forks of the Toklat, Sheldon visited a golden eagle's nest and found the bird on her nest while ". . . on the rocks nearby were strips of skin and other remains of lambs, demonstrating that this eagle at least had been successful." Ewes and their lambs more than 6 weeks old, seem to be indifferent to eagles.

On May 27 we located a band of ewes and small lambs that had bedded down on the very summit of a pinnacle rock. Cliffs dropped away on all sides but one. There was considerable snow in patches at this elevation (about 3,500 feet). Here, for the better part of an hour, I watched two ewes and their lambs. By peeking through a crack in the rock at a distance of 75 yards I was able to study them unobserved. One or the other of the two female sheep stood guard constantly (fig. 80). After a 10 minute period of watching in all directions the ewes changed places. On another nearby rock I found 20 sheep, 10 ewes and 10 small lambs, lying down and chewing their cuds contentedly. The ewes' coats were very ragged and the animals were thin. Their sides and under parts were stained brown from contact with wet soil, although the sheep I observed were resting on well drained, dry ground. After securing a series of photographs I stood up in plain sight. Upon my sudden appearance the old ewe on guard jumped fully 20 feet, straight down into a deep snowdrift on the south side of the rock. One ewe with a very small lamb turned around and tried to escape another way, but finding that this was impossible, she turned back and, leading the lamb, followed the way that the others had taken. It would have been utterly impossible for a man to go down the steep cliff and across the snowslide which was traversed with ease by the sheep. Even the lambs never hesitated a moment and seemed to enjoy the run. I endeavored to follow the sheep but found this was impossible and was forced to turn back and seek another route. At length I again found the whole band of sheep feeding contentedly on a steep talus slope a thousand feet below.

Figure 81.—A sheep lick (center) on Ewe Creek. Photograph taken May 25, 1932, Ewe Creek. W. L. D. No. 2967. |

On July 27, 1926, I found a flock of about 20 sheep sleeping in the shade during the heat of the day under some conglomerate cliffs which formed an outcrop high up on a ridge at an elevation of 5,000 feet. Here I saw an old ewe accompanied by her lamb of the year and by her previous year's male lamb. The latter had horns about the length of those of his mother. They were all feeding together; and they kept together even when I approached. I followed them about for some time in order to make sure that both lambs belonged to this particular ewe. There was no question regarding her anxiety and care for both offspring.

In the McKinley district mountain sheep visit certain "licks" or mineral springs at regular intervals, usually about every other day during the spring. One of the best known licks is located on Ewe Creek (fig. 81), just within the park boundaries on the north side of the secondary range. Here we found that sheep had established regular highways leading from the higher ridges down across the gravel-strewn plain to the springs which cover an area of about one-quarter of an acre. These well-traveled trails (fig. 82) were visible to the naked eye a mile distant and doubtless had been traveled by countless generations of mountain sheep. They were as nearly straight as the contour of the land permitted. Another lick is located on the divide near Double Mountain, between the Sanctuary and Teklanika Rivers. This latter lick is visited perhaps more frequently by caribou than by sheep, although we found numerous tracks of both animals there early in July. The sheep visit the licks for the mineral salts which they obtain there. It is thought by persons who are familiar with the animals that the reason for sheep visiting the licks in the spring is that certain mineral requirements have been lacking in their winter food. Perhaps such visits may also assist in the shedding of their hair which is molted at this time. The lick on Ewe Creek was located on a high bank of the stream. Several beds of talc were exposed and in one place where the rock is of a purplish-slate color, an area of about 20 by 30 feet is literally covered with sheep tracks where the animals have come to lick and gnaw off portions of the soft rock. In some cases the rock is worn off by licking and undercutting to a depth of 6 or 8 inches. I tried tasting some of this formation which the sheep sought but there was no decided taste that I was able to detect. Samples of the rock were saved and brought back to the University of California, where they were analyzed by Dr. G. L. Foster, of the Division of Biochemistry. He reports that calcium and iron phosphate are the two minerals present in this material which would be soluble in digestive fluids, such as the gastric juices of the mountain sheep's stomach. He also found certain insoluble substances present, chiefly magnesia and silicates. Our observations indicate that such licks were not frequently visited by the sheep after the first of June. By the middle of June the sheep move to their summer range, some 15 or 20 miles distant, and there is no opportunity for them to visit these particular licks during the summer.

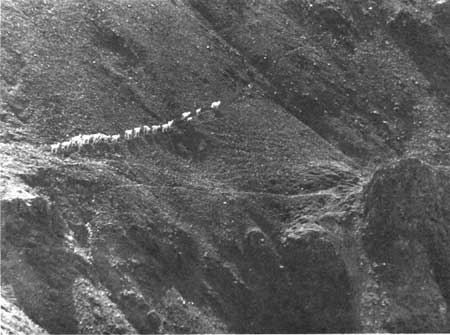

Figure 82.—This old Dall sheep trail

was 14 inches wide and worn 3 inches deep in rocky ground.

Photograph taken June 5, 1926, Savage Canyon. M. V. Z. No. 5203.

The mountain sheep's daily program during the summer was as follows: Through the early morning hours, from 3 o'clock until 8 o'clock they foraged about actively, often descending nearly to timber line. By 10 o'clock they returned to the higher cliffs (fig. 83) and during the heat of the day were found bedded down at the foot of perpendicular cliffs or escarpments which protected them from the unexpected approach of any enemy from above. They directed their watch downward and were able to detect readily the approach of any enemy from below. Six o'clock in the evening usually marked the time of the second grazing period in the day.

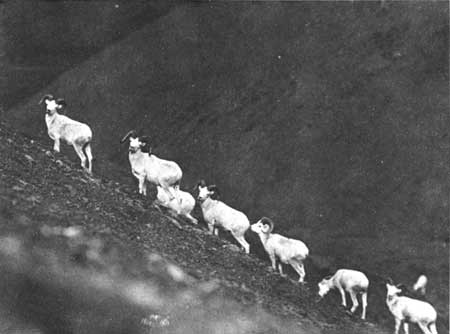

Figure 83.—A flock of Dall sheep

returning to the cliffs for their midday rest.

Photograph taken July 20, 1932, Igloo Creek. W. L. D. No. 2719.

At Double Mountain on July 9, 1926, I watched numerous bands of mountain sheep bedded down on rocky ledges near the top of a rugged cliff. At about 6 o'clock in the evening the sheep began to come to life and several old rams started down the talus slope to feed in the green meadows below. Soon there was a veritable avalanche of sheep pouring down the hillside, forming a long stream from the cliffs to the meadows. Sixty-three sheep were counted on one hillside in an area less than 40 acres in extent. The old rams fed fearlessly even down among the willows where the grass was tall and tender. A band of caribou came over the pass and mingled with the sheep as they all fed. Nearly half of the adult sheep were rams; one in particular was very large and had nine growth-rings on his horns. This adult ram stayed with the band of ewes, but another flock of 11 young rams stayed together in a band by themselves. They were very curious and were not afraid of me. Some of them stood and watched me for awhile. Then they lay down though they continued to watch. By walking slowly toward them I was able to get within 50 yards of the entire flock. This band of sheep fed slowly and were still grazing when I left them at 10 o'clock in the evening.

On the evening of June 24, 1926, at the head of Savage River, a flock of from 50 to 60 sheep was observed feeding along the lower edge of a melting snowbank. Just as the last rays of the setting sun turned the whole landscape into gold this flock ceased grazing, walked over to a bare open ridge, dug out beds in the gravel with their front feet, and at 11 o'clock all lay down for a short night's rest.

In traveling from their homes amid the cliffs to the forage grounds below, the sheep pass over rock slides and cause numerous rocks to become loosened and to plunge down the steep slopes. At Double Mountain on July 22 we found that the sheep were constantly dislodging rocks in this way. They were very keen to the first indicating sound of this danger and each member of the flock gave instant heed in order to avoid any jeopardizing slippage from the cliffs above them. We found that it was exceedingly perilous in such localities to try to approach sheep from below. On one occasion a rock the size of a nail keg plunged down the mountainside past us, missing us by a close margin. We found one dead sheep which had been caught and killed in a snow or rock slide and another large ram with a broken leg which we believed had been injured by falling rocks. For this reason, we caution park visitors not to get below the sheep on a rocky slope and to be extremely careful themselves when traveling in a group.

The only time that we heard Dall sheep utter any audible sound was when two yearlings approached a band of four adult rams. On this occasion, while the yearlings were running toward the rams they were heard to make a sound somewhat like the bleat of a domestic sheep, except that it was deeper and harsher.

The sense of sight in the mountain sheep is exceedingly keen, whereas their sense of smell does not seem to be very sensitive. When observed at close range, their eyes seem very large and dark and in marked contrast to the whiteness of their bodies. Charles Sheldon reports (1930, p. 148) one ewe with yellow eyes. It has been observed that if a person remains off the skyline and motionless, Dall sheep will often pass without detecting his presence—even at 50 yards distance. Too, this may happen when the wind is blowing directly from the man toward the sheep. Thus on June 12, while I was watching a band of these animals as they were returning from a salt lick, they passed within 50 yards of me and were unaware of my presence although the wind was blowing directly from me toward the sheep.

When frightened by some sudden shock the Dall sheep show a slight tendency to rush together. One would naturally suppose that thunder would have little or no effect on them. Contrary to our expectation, the thunder did seem to affect them. On June 1 when we were on one of the sheep mountains there occurred a sudden and extremely heavy clap of thunder. As we looked back, a compact band of sheep was rushing through the pass where we had been a half hour earlier. There were more than 70 in the flock, not counting an abundant sprinkling of lambs. Suddenly there was another clap of thunder and the sheep dashed madly up the steep slope. We had had this flock under observation throughout the forenoon and were unable to ascribe any other cause for their fright than the unusually heavy thunder.

On the whole, the Dall sheep is of a retiring, we might even say timid, disposition; yet he is curious. By repeated experiments we found that if we tried to sneak stealthily up to a band of sheep they would become alarmed and would run away, whereas, if we advanced slowly, in the open, and were visible to the band at all times, in many instances they would be interested rather than afraid and might even advance toward us, if we stopped and remained perfectly still. As a further test we tried making considerable noise, although we remained as nearly motionless as possible the while. Instead of becoming alarmed we found that our shouting merely excited their curiousity. One old ram in particular kept coming toward us, evidently eager to find the cause of all the racket.

On June 28, at the head of Savage River, I approached quietly and very slowly to within 30 steps of a young ram that was very curious to learn what sort of an intruder I might be. This ram, his nostrils dilated, stretched his neck and made every effort to identify me by scenting me. As I stood quietly watching, he shifted around until he was directly to windward of me, but he was evidently still baffled. Finally he indulged in a favorite trick of mountain sheep; he bounded off over the ridge as though in full flight, but finding that I did not follow he promptly returned and cautiously peered back over a rock pile, just his white head showing and even that blending with the white clouds in the sky.

The enemies of mountain sheep fall into two classes, the first being predatory birds and mammals and the second, man. The golden eagle is a potential enemy of young lambs but apparently does not levy a heavy toll. Sheldon found sheep remains at a nest but these may have represented carrion, for these eagles are known to feed on carrion. Among mammals, the wolf, coyote, lynx, and possibly wolverine prey on sheep but it appears that the sheep are usually able to escape these enemies if they are not surprised too far from the friendly cliffs. This is probably one of the main reasons why the Dall sheep remain close to broken rocky ground and cliffs where they may flee for refuge when pursued by either wolves or coyotes. On June 16, 1932, at 10 o'clock in the morning, I watched a large gray coyote trying to ambush a band of 80 ewes that were attempting to cross a broad low valley between their winter and their summer range. The coyote hid in the low bush near the trail where it crossed open ground. The sheep saw the coyote and several times many of the nervous ewes fled wildly back to the protection of the cliffs. Sheldon (1930, p. 368) let his dog chase a 3-year-old ram, which had a start of 100 yards, in order to observe how a sheep chased by a wolf might behave. The dog gained at first but when the ram made a steep slope he easily kept in the lead, stopping at short intervals, apparently but little worried, to look back at the dog, which soon became too tired to follow. Sheldon remarks (p. 369), "The actions of the ram led me to suspect that a wolf would not have followed more than a few feet up such a slope, its experience, which Silas lacked, having taught it that a sheep could easily escape when once headed upward on a steep slope." In May 1932, the remains of three sheep were noted out on the open ground. These sheep may possibly have been killed by wolves. Under normal conditions the sheep seem well able to fend for themselves.

In the Mount McKinley region, man has been an outstanding enemy of mountain sheep. In the olden days, before the park was established, market hunters made a regular business of shooting sheep in the region, and of sending the meat to the mining centers along the Tanana River. According to the testimony of reliable men and also as evidenced by the numerous pairs of bleached horns which still remain in the vicinity of the many crude log shelters that served as winter camps and are still extant along the Savage and Sanctuary Rivers, hundreds of sheep were slaughtered each winter.

The older rams are less fearful of enemies and are more independent than are the smaller sheep. This was well shown by the actions of two large males found on July 27, on the very summit of a pinnacle rock. Their eyes were closed and they were chewing their cuds in perfect contentment. Upon my very slow approach from above the younger sheep amid the ewes fled, but the sleeping rams allowed me to get within 50 yards of them. Finally the smaller of the two rams, which had a broken horn, possibly injured in some recent fight, detected some slight movement. He stood up and came over to investigate; the larger, 10-year-old-ram—as shown by the growth rings on his horns—continued to doze peacefully until I approached to within 60 feet of him. Even then he did not see me but became alarmed because of the flight of the smaller sheep and the falling rocks from the cliff behind him, and rising to his feet he stood with distended nostrils (frontispiece) looking intently in every direction in his attempt to locate the cause of the disturbance. His only avenue of escape was by way of the narrow ledge on which I was standing, for the cliffs dropped off on all sides from 50 to 200 feet. Suddenly the old ram lowered his head and bounded towards me. One might have thought that the ram was charging at me; however, I feel sure that this was not the case. He made no effort to molest me though he was so close to me as he passed that I could have reached out and touched him. He merely seemed very anxious to escape and join the rest of the flock on the heights.

It has been said that the old rams do not mingle with the ewes and younger sheep during the summertime. For the most part this is true. However, there are exceptions. On July 26 a large band of mountain sheep was found bedded down at the foot of a high cliff on Mount Margaret; in their midst was one old very broad and deep-chested ram, one of the largest of the 3,000 to 4,000 which we observed. At another locality on July 27, near the head of Savage River, two large rams were found bedded down on top of a pinnacle rock. They were accompanied by numerous yearlings and one old ewe with her offspring of the year. At various other times in the latter part of July we found some of the males mixing freely with the adult females and young. Prior to this, that is during May and June, the old rams usually keep in small, isolated flocks, three to eight being found together. By August the young rams, those from 3 to 5 years old, indulge in sparring and fighting, so at this time there is much rushing together and bumping of huge horns.

At Double Mountain on July 22, 1926, the younger rams were beginning to feel belligerent or playful, and we watched numerous jousts or contests. The procedure was as follows: Five or six young rams would congregate forming a circle of from 10 to 12 feet in diameter (fig. 84). A ram would select an opponent apparently by looking at him intently; then he would back off. If the opponent accepted the challenge he likewise would hurriedly back away until each had retreated a distance of between 20 and 30 feet. Then after pausing a moment they would dash at each other, meeting head-on at the center of the ring. Just before they collided they would rear up on their hind legs and strike their horns together with a resounding thud which was clearly audible to us, as we sat watching the sheep with binoculars, a quarter of a mile distant. This would some times be repeated three or four times until one or the other of the contestants was worsted and then a third ram would often step in and challenge the winner. At these times the older rams keep to themselves, but on occasion they were seen to seek the company of some adult ewe.

Figure 84.—Right is being determined

by might in the circle of young rams (Ovis dalli) at extreme upper right.

Photograph taken July 22, 1926, Double Mountain. M. V. Z. No. 5200.

The mating season of mountain sheep in the McKinley region has been found to vary from season to season. Charles Sheldon, who spent the winter of 1907-8 in the Toklat region studying the habits of Dall sheep, reports (1930, p. 198) that he observed the first actual mating of mountain sheep on November 6, 1907, also that it was the first positive sign of the rut. The bands of rams had broken up in October and the older rams had traveled about the mountains but they had not joined the ewes until the latter part of October. By November 18, the rutting season was at its height and it "continued until the middle of December." Sheldon (1930, p. 209) points out that at the height of the rut several rams were observed to serve several ewes of the same flock as they came in season, and ". . . not once did any of the four rams show any sign of jealousy or pugnacity." However, if a strange ram from another flock of sheep enters the field during this season his right is challenged by the local rams and a crashing battle ensues. The ewes look on such contests with mild interest and the ram that is beaten merely moves off toward some nearby flock leaving the victor the undisputed master.

To reiterate briefly, in midwinter these hardy sheep, clothed in their heavy coats of long winter hair (fig. 74), seek the comparatively snow-free, high, barren slopes and are seemingly indifferent to the cold and winds. They paw aside the snow in order to reach the stunted growth of grass and herbaceous plants which comprise their food at this season. So long as they remain on the steep slopes they are relatively safe from sudden attacks by wolves or other natural enemies. In August 1932 former Ranger Lee Swisher told me that at that time he did not believe there were more than 1,500 sheep in the entire park, as contrasted with a count and estimate of between 10,000 and 15,000 that he had found present on his patrols over the same area in 1929 when the mountain sheep population was at its highest peak. The explanation of the reduction is not clearly understood but it has been attributed variously to (1) starvation and death caused by heavy snowfall and prolonged winter weather (fig. 85); (2) failure of the surviving sheep to reproduce, due to their poor physical condition; (3) destruction of many sheep by coyotes and wolves. The problem needs careful investigation.

Figure 85.—Following a hard winter

and scarcity of food in 1932, many ewes ran no lambs, note 13 ewes and

only 1 lamb (centre), ordinarily, at least half of these ewes would have had lambs.

Photograph taken August 26, 1932, Sable Mountain. W. L. D. No. 2713.

Top

Top

Last Modified: Thurs, Oct 4 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/fauna3/fauna10e2.htm

![]()