|

Crater Lake Historic Resource Study |

|

VIII. Roads of

Crater Lake National Park (continued)

B. Entrance Road and Bridges (continued)

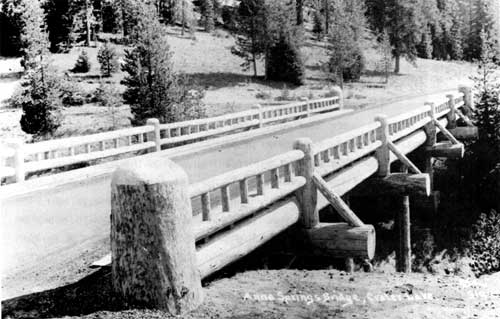

8. Annie Spring and Goodbye Creek Bridges

Construction on the new rustic Annie Creek (or Annie Spring) bridge across the Annie Creek gorge began in 1925 and was completed in 1926. A three-span timber structure seventy-eight feet long, it was built by the Public Roads Administration under contract. By the end of that year the upper end of the Crater Lake highway was receiving a heavy coat of shale to provide a solid base for vehicular traffic. [33]

The early history of the Goodbye Creek bridge is hazy. According to park information, a Goodbye Bridge, so-named because it was the last item of construction accomplished by Superintendent Arant before his retirement, was built in 1913. A report of a park resident engineer, however, states that

the original Goodbye Creek Bridge located on the main road to the Rim between Annie Spring and Park Headquarters was constructed, under contract, by the Public Roads Administration in 1926. It was a three span, timber bridge, native Shasta Fir being used and short life was expected. [34]

The bridge was a temporary structure because relocation of the road between Annie Spring and the rim was under discussion and funds for a permanent bridge could not be requested. A 1929 news article, on the other hand, announces the completion of Goodbye bridge on July 27, 1929, marking

the end of an era in construction of oiled roads in Crater Lake National park. It is the last link in the high standard highway between Meford and the lake on the west, and Klamath Falls and the lake on the south. Built under the supervision of the United States bureau of public roads, this difficult piece of construction required the work of on an average of 10 men per day, over a period of six months. It was erected at the cost of approximately $10,000. [35]

This bridge was made of heavy peeled hemlock to conform in design to the Annie Spring bridge, and was 240 feet long, 74 feet high, and 24 feet wide with eight 30-foot spans, double truss:

The railing is effective in its simplicity, being made of balasters and rounded posts. The average dimension of the timber is 30 inches in thickness, set on concrete pedistles [sic]. The flood [floor] of the bridge is of 2 by 6 laminated deck. [36]

A June 1930 newspaper clipping mentions an extension being built on the Goodbye bridge. [37]

9. Plans Made for Second Rim Road

By the fall of 1928 the rim area could be reached by a new oiled road from the west boundary that had replaced the old hazardous route with its 11% grades with a new one containing a maximum of 6-1/2% grades. At the rim a new oiled road was completed distributing traffic to the new cafeteria and cabin group, to the campground, and to the lodge at the opposite end of a half-mile-long plaza. On each side of the boulevard area was an eighteen-foot parking strip to accommodate several hundred vehicles and along the edge of the crater a wide asphalt promenade for pedestrians had been constructed. [38]

The next large undertaking of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads within the park would be construction, beginning in 1931, of a modern standard-grade rim road to reroute the existing one, which was passable but which did not closely follow the lake rim. Despite its steep grades, sharp curves, and dusty condition, it had been used by many park visitors. While location surveys were underway for the new road in 1929, two projects were started on the east entrance road to the park. The Sand Creek park boundary project, 4-2/10 miles long, was an approach road from The Dalles-California Highway to the east entrance of the park, while the Lost Creek project consisted of two miles of road work within the park. These 6-2/10 miles of road at the east entrance outside and inside the park had been surfaced. The 1-3/10 miles of grading from the end of the surfacing project to the Lost Creek ranger station were to be finished that season. This road served as a connecting link between the main roads through the park and The Dalles-California Highway to Bend, Oregon, the southern end of the new Willamette Highway between California and the Willamette Valley. A surfaced parking place was constructed this year at the Pinnacles. [39]

Illustration 20. Annie Spring bridge, 1929. Courtesy Southern Oregon

Historical Society.

By the first of May 1931, bids were being called for to grade the first six miles of the new rim road from the lodge area around the west side of the lake to the North Entrance ranger station at the Diamond Lake junction. Work was begun in June using three gasoline power shovels, one steam shovel, fifteen trucks, several air compressors, and other equipment. Approximately 120 men were employed in 1931 for a period of five months. A new south side route now brought tourists to a vantage point at Sun Notch. Surveys were also completed for the balance of the route north to Diamond Lake and for connections down Union Creek to the Medford road and east to The Dalles-California Highway. [40] In July construction on three projects was reported delayed because of the excessive snowfall of the previous winter. A Portland construction company was preparing to complete the grading of the first six-mile unit of the new rim road begun the previous year. One hundred laborers would be at work on two eight-hour shifts to assure completion that year.

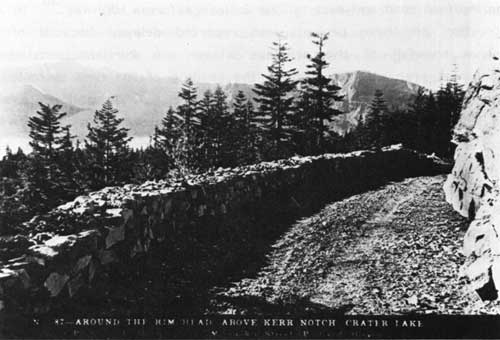

Another construction company had fifty men working on the portion of the rim road leading from a point near Lost Creek to Kerr Notch, a distance of 4-1/2 miles necessitating clearing of timber and grading, a project also begun the year before and expected to be completed in the fall. A third company was working on the Diamond Lake road in the park with fifty men completing a 1931 project of eight miles. [41] More than 100 men were again employed on the rim road for four months in 1932, and it was projected that the road would be extended to the Wineglass, in 1933 to Kerr Notch, and be completed in 1934 with the construction from Kerr Notch down Sand Creek to Lost Creek, then up to Sun Notch, down to park headquarters, and up to the rim. [42]

In 1933 only two months' labor was possible on the rim road as a result of deep snowdrifts. By July four contracts for road construction in and near the park were getting underway. Laborers were being employed through the relief agencies of Klamath and Jackson counties. Because of snowdrifts twenty-five feet deep that had to be removed, work could not begin until August 15. During blasting operations in 1933 on the rim roadway, traffic around the rim was permitted. Projects to be accomplished during the summer included grading of the next eight-mile unit of the rim road from the end of the previous contract at the North Entrance ranger station and fourteen miles of surfacing from the Rim Village area to the north park boundary (final grading of this section was completed, in 1935); grading of the next four-mile unit on the east rim, begun and completed in the 1933 season; 5-1/2 miles of grading from the boundary to the southern end of Diamond Lake outside the park; surfacing of 4-1/2 miles of the east entrance road to Kerr Notch; and grading eighteen miles of the Union Creek entrance to Diamond Lake, continuing from where the five miles of grading was completed the previous year. [43]

Illustration 21. Rim drive above Kerr Notch. Courtesy Southern Oregon

Historical Society.

By 1934 the surfacing of the lodge-North Entrance ranger station section of the rim road was completed; the Diamond Lake route from the north entrance to the park boundary was to be oiled in 1935. Construction of the second unit of the rim road, from the north entrance to the Wineglass, was more than 50% complete. The third unit of grading, from the Wineglass to Cloudcap, was completed in 1934, leaving for future work the distance from Lost Creek to Government Camp. [44] In addition to major road projects, cut-stone curbing was placed around all driveways in the Government Camp area that year, and at the rim similar curbing was placed around the lodge and part way from that structure to the cafeteria. [45]

The route of the rim road had to be changed to some extent to reduce the grades in reaching Cloudcap, the highest point on the road. The next four miles of grading were to be completed during the 1936 season, bringing the rim road to Kerr Notch on the east side of the lake, leaving only nine miles of construction not yet started. A contract for four miles of the work, during which the road would diverge from the old bed and be built higher on the slopes, was to be let in early 1936; the remaining five miles to park headquarters would be left unchanged from the present route. Surfacing activities followed grading on the west rim, and were to be accomplished on a stretch of the rim road from the North Entrance ranger station to Cloudcap. [46] It was still hoped that the rim road would be completed by or during the 1939 season.

The new rim road had been designed to skirt the edge of the crater whenever possible to provide scenic vistas, but because of the rough nature of the ground it was difficult to build a standard-width road with few curves and steep grades. Short working seasons also hindered progress. Because of the difficulties encountered, the thirty-five-mile road averaged about $60,000 per mile. It followed the old roadbed whenever possible, and efforts were made to preserve the route's natural features. Native trees and shrubs were planted in denuded earth cuts whose slopes were rounded to prevent sliding. The obliteration of the old rim road was accomplished by planting trees and shrubs and by applying sod. The new rim road connected on the north side of the lake with the North Entrance highway leading to Diamond Lake and to The Dalles-California highway. On the east the road connected with the East Entrance highway to The Dalles-California Highway at Kerr Notch. At park headquarters the road made a junction with the South and West entrance highways. [47]

The rim road could only be traveled three to four months out of the year because of snow depths. The all-weather road to the park boundary was kept open, but from there only the segment to the administrative headquarters and parking lot near the rim was kept free of snow. In 1961 the present road between Annie Spring and the rim was reconstructed. In 1971 the rim road was made one-way.

Another part of the road system within the park was the Grayback Ridge Auto Nature Trail, a one-way, four-mile, dusty road connecting the Rim Road and Lost Creek Campground. It was closed to auto traffic in 1980.

10. Motorways

"Motorways" was the term given to the one-way, low standard truck trails constructed within the park primarily for fire protection. Emergency Conservation Work crews during 1933 accomplished construction of thirty-two miles of new trail and maintenance work on eighty-two miles of old motorways. Truck trails constructed during the 1933-34 seasons were those at Sun Creek, Crater Peak, Wineglass, Timber Cone Crater, and Bear Creek; the Union Peak Loop; and trails between Lost Creek Ranger Station and Vidae Creek Falls and between Castle Creek and The Watchman. [48]

11. Restraints Imposed by Snow and a World War

Originally Crater Lake National Park operated only in the summer, and as a result, park improvements and facilities had been oriented toward seasonal use. In the early 1930s a plan for removing snow from the park roads as it fell was tried experimentally and proved satisfactory. As a result of the demand of winter sports enthusiasts, park roads were opened to visitors for the first time during the winter of 1935-36 in cooperation with the Oregon State Highway Commission, which kept the snow plowed from the approach roads as far as the park boundary The National Park Service first regarded winter operation of the park as a service only to winter sportsmen, but upon realizing that many people liked to see the park in the winter months, the government adopted a policy of year-round use. After that the park was kept open and accessible throughout the year except during the Second World War when snow removal equipment was loaned to the army; the staff reduced from twenty-five permanent employees to eight or nine; transportation, lodging, meal, and boat services suspended; the interpretive staff abolished; administrative, protective, maintenance, repair, and operational services curtailed to a minimum; and surplus trucks, tools, equipment, and supplies disposed of to war agencies. The main effort of the remaining park staff during that time was devoted to protection of the park from fire during the summer months. [49]

12. New Bridges Needed

In 1936 a new rustic-style bridge was completed over Munson Creek near the ranger dormitory, replacing one that had been used for many years. In 1940 the Annie Creek bridge was found to be badly decayed, and immediate repair was recommended. Late in the fall of 1940 a king post truss was erected on the center span, which carried the structure through the winter of 1940-41. In the spring of 1941, however, the bridge was condemned, and funds were allotted for temporary repairs in September, including the placement of concrete footings. Maximum use of only 1-1/2 years was anticipated. [50]

Also in 1940 immediate repairs were recommended for the Goodbye Creek bridge to carry it through the winter of 1940-41, but in late 1941 it too was condemned for vehicular use and all trucks and buses were detoured around the bridge on the old road. Funds were allotted in the fall of 1941 for construction of a temporary detour bridge about 200 feet upstream from the old one. This was a three-span, standard-frame structure, 69 feet long Douglas fir was used for the decking. Clearing and grading for the bridge approaches were kept to a minimum, anticipating only two to three years' use. [51] In 1945 construction of a detour road around Annie Spring became necessary due to the unsafe condition of the old log bridge spanning the creek, which had to be rehabilitated. The logs used for the walls and barriers along the approach to the detour were procured from the old Goodbye Bridge. [52] In 1946 plans for replacing the Goodbye Creek bridge had been completed, and work on the Annie Creek bridge plans was underway. [53] The old Goodbye Creek bridge was replaced finally in 1956 and the old Annie Creek bridge was replaced about the same time.

Other early bridges within Crater Lake National Park included:

1. Bridge at Pole Bridge Creek on the Fort Klamath Road; timber, one span, 16 x 14 feet, built by War Department in 1914.

2. Bridge on White Horse Creek, Medford Road; timber, three span, 40 x 14 feet, built by War Department in 1916.

3. Bridge on Little White-Horse, Medford Road; timber, two span, 30 x 14 feet, built by War Department in 1915.

4. Bridge on Wheeler Creek, Pinnacles Road; timber, two spans, each 15 feet, 30 x 14 feet, built by War Department in 1913.

5. Bridge at head of Wheeler Creek, Rim Road; timber, one span, 15 x 14 feet, constructed by War Department in 1914.

6. Bridge on Rim Road; timber, three 15-foot spans, 45 x 14 feet, built by War Department in 1913. [54]

7. Bridges (two) over Cavern Creek in Lost Creek District. Old log bridges collapsed under snow load; new ones built in 1941. [55]

13. Evaluations and Recommendations

Because of their initial construction as temporary structures, the first bridges in Crater Lake National Park were ultimately replaced as soon as funds were available. Originally built for horse-drawn vehicles, the structures soon proved inadequate for heavier traffic. None of the bridges within the park are recommended as being historically significant.

The rim road built around the caldera from 1915 to 1919 was without doubt the single greatest achievement in the development of a road system within Crater Lake National Park. Extremely difficult problems were encountered due to the rough terrain and short working season--problems peculiar to this particular road-building activity. Although the new road begun in 1931 followed the old route whenever possible, the unfavorable features of the old road were entirely eliminated. At the same time, portions of the old road were obliterated by the planting of shrubs and the application of sod, so that in many places it became impossible to detect the course of the older route. Portions of the old rim road are now being used as trails. Due to a lack of integrity, the rim road is not considered eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

crla/hrs/hrs8c.htm

Last Updated: 14-Feb-2002