|

Cowpens

Administrative History |

|

Chapter Three:

DESIGNATION OF COWPENS AS A NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD

Early Attempts to Enlarge Cowpens

The 1929 designation of Cowpens as a national battlefield site did not satisfy the continuing desire of battleground supporters to have a full-scale park comparable to those at other southern Revolutionary War battlefields. In 1940 local residents stepped up their pressure on the National Park Service to further enlarge and develop the site. A February meeting of community leaders from Cherokee and Spartanburg Counties was called by Harry R. Wilkins, an insurance agent in Spartanburg and a Cowpens enthusiast. Among those attending the meeting were A.W. Askins, a Coca-Cola bottler and president of the Cherokee County Improvement Association; Frank W. Sossamon, business manager of The Gaffney Ledger and president of the South Carolina State Press Association; S.S. Wallace, Jr., publisher of The Spartanburg Herald-Journal; and Floyd W. Kay, secretary of the Spartanburg Chamber of Commerce. The meeting attendees created a steering committee and elected Askins as the chairman. Although the meeting was held in Spartanburg and included Spartanburg County leaders, the steering committee decided to give Cherokee County leaders the primary role in lobbying for Cowpens. The committee expected help from the state's congressional delegation, including Senators James F. Byrnes and "Cotton" Ed Smith; Representative James P. Richards, whose district included Cherokee County; and Representative Joseph R. Bryson, whose district included Spartanburg County. [1]

Seeking to pressure the Department of the Interior and the NPS to expand and develop Cowpens, Clara C. Phillips and Edith Fort Wolfe led a delegation of Daniel Morgan NSDAR Chapter members to Washington for a meeting with Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. In response, NPS Coordinating Superintendent Elbert Cox of Yorktown attended Gaffney and Spartanburg meetings with local leaders to discuss the issue. In addition, Mrs. Charles M. Drummond of the Cowpens NSDAR Chapter offered to donate the Washington Light Infantry Monument tract for inclusion as part of the national battlefield site. While thanking the local community for its interest in the battlefield, NPS officials responded to the requests for an expanded Cowpens site with several points. First, the federal legislation had authorized the site with a limit of one acre in size. Second, the costs of land acquisition, development, and continued maintenance were beyond the capacity of the Service at that time. Third, Cowpens lacked desirable features present at other southern Revolutionary War battlefields, such as earthworks and other battle-period remains. In short, the NPS urged local battleground supporters to focus their attention on improving Kings Mountain NMP and using its interpretive program to highlight the Cowpens story. World War II further postponed expansion efforts as the nation's attention was focused on military needs. [2]

After the war, supporters of an enlarged Cowpens site mounted another effort. Around 1947, a prospectus for a "Cowpens Battleground NMP" was prepared by a committee under the sponsorship of the Daniel Morgan Chapter, the City of Gaffney, the Gaffney Chamber of Commerce, and other patriotic and civic organizations in that city. While preparing the prospectus, the committee received planning assistance from Albert Schellenberg, the head of plans and design for South Carolina's state parks. Based on Schellenberg's recommendations, the prospectus called for a national military park with on-site staff, a boundary including the core battlefield area, a museum, expanded parking, and a superintendent's residence. In addition, the committee planning the prospectus at some point considered proposing an observation tower at the battlefield. [3] In the absence of such developments, the prospectus warned that "the Cowpens Battleground is doomed to oblivion." [4] In conjunction with these efforts, the committee unsuccessfully sought to have Daniel Morgan's remains relocated from Winchester, Virginia, to Cowpens, and Southern Railway named one of its Pullman cars after the battle. During both 1947 and 1949, South Carolina's Senator Olin D. Johnston of Spartanburg and Congressman Richards introduced bills in Congress to create a national military park of one hundred acres. The bills died in committee. [5]

As part of this Cowpens effort, Wilkins wrote a song about the battle to provide publicity for the site. Entitled Cowpens Battleground, the song was composed by Geoffrey O'Hara, a prominent New York composer. O'Hara's services were paid for by Francis Pickens Bacon, a great-great-grandson of Colonel Andrew Pickens. The song was first presented before the public during a 1948 battle anniversary observance at Limestone College in Gaffney. The song was subsequently published with the proceeds being donated to four local NSDAR chaptersCowpens in Spartanburg, Kate Barry in Spartanburg, Mary Musgrove in Woodruff, and Daniel Morgan in Gaffney. In addition, Professor Merrell Sherburn of Limestone College donated his time to compile a band arrangement for the song. With funding from the Spartanburg County Foundation, Wilkins printed and distributed one thousand copies of the band arrangement to military, school, and college bands throughout the nation. [6]

Local NSDAR chapters continued urging the NPS to enlarge Cowpens during the 1950s. In 1951, the Cowpens Chapter once again discussed donating the Washington Light Infantry Monument tract for inclusion in the site, but the NPS did not act due to concerns over increased maintenance and the lack of legislative authority for further land acquisition. Acting as regent of the Daniel Morgan Chapter, Phillips wrote a letter to the regional director in 1953 requesting improvements and expressing the complaints of visitors to the site. Specifically, she mentioned the lack of directional signage, brochures, and a paved walk to the U.S. Monument. As instructed by the regional director, Kings Mountain Superintendent Moomaw met with Phillips, Wolfe, and other Daniel Morgan Chapter members to discuss conditions at Cowpens. He pointed out the limited funding available for the site, the lack of legislative authorization for an expansion, and the high costs of land acquisition and development for a full park. Though Moomaw doubted the financial feasibility of expansion, he reported to the regional director that the NSDAR chapters would probably continue to push local community leaders and politicians for federal legislation and funding. [7] According to Moomaw's report, the Daniel Morgan Chapter representatives "admitted that all of this is being brought up because they and the Spartanburg Chapter resent the development at Kings Mountain, Guilford and Yorktown by our Service and that as far as they are concerned Cowpens is virtually ignored." [8]

|

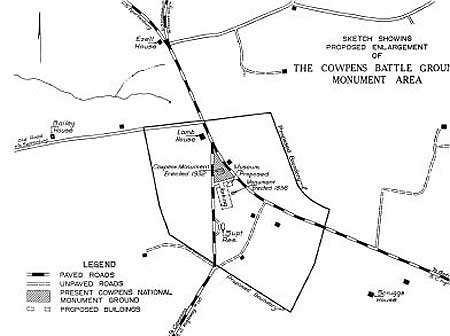

| Figure 9: NSDAR map showing proposed development for a "Cowpens Battleground National Military Park," circa 1947 |

Moomaw hoped that Mission 66 improvements at Cowpens would lessen the pressure to expand the site. In 1956, he attended meetings of both the Daniel Morgan Chapter in Gaffney and the Cowpens Chapter in Spartanburg to present the Mission 66 plans for the site. In addition, the NPS cooperated with the Daniel Morgan Chapter to make a minor addition to the site in 1958. With the relocation of Highway 11 during the 1930s, a one-fourth-acre strip of land separated the Cowpens site from the new highway. Moomaw devised a plan where the NSDAR chapter would purchase the land for donation to the NPS. Before that could occur, however, congressional legislation authorizing an increased site boundary had to be passed. In January 1957 Johnston introduced a Senate bill to expand Cowpens by a maximum of one acre through donation. On July 18, 1958, Senate Resolution 602 was signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower after passing both the Senate and the House. In late 1956 the Daniel Morgan Chapter bought the tract, and the donation was finalized by 1961. Moomaw undertook "quiet missionary work" to increase local support for closing the old Highway 11 that separated the two NPS tracts. With Cherokee County officials agreeing to close the road, the two tracts formed an enlarged Cowpens site that the Service improved under Mission 66 as discussed in the previous chapter. [9]

A Renewed Drive to Expand Cowpens

An August 1966 editorial in The Gaffney Ledger by editor Bill Gibbons sparked renewed interest in creating a full-scale national battlefield at Cowpens. Among other things, the editorial complained about the small size of the Cowpens NBS in comparison with Kings Mountain NMP, especially given the significance of Cowpens. Following up on the editorial, Frank W. Sossamon, the newspaper's publisher and a veteran of Cowpens expansion efforts, contacted South Carolina Senators Strom Thurmond and Donald R. Russell along with Congressman Tom S. Gettys to urge congressional action. Responding to an inquiry from Gettys, Kings Mountain Superintendent Moomaw noted a revival of local interest in Cowpens, thanks largely to the continuing efforts of Wilkins. After consulting with local property owners to gain their support, Gettys introduced a House bill to expand the site in October 1967. Senator Ernest F. Hollings, Russell's successor, introduced a companion Senate bill in January 1968. In response to these actions by the state's congressional delegation, the NPS began assessing options for greater development at Cowpens. [10]

This renewed drive came during a period of rapid expansion in the national park system under George B. Hartzog, Jr., who served as NPS director from 1964 to 1972. During his nine years in this position, Hartzog created nearly as many new parks as had been created during the previous thirty years. Beyond the sheer number of new parks, his administration was marked by its emphasis on recreational areas, environmental education, and new interpretive techniques. Coming during the era of the Great Society, this growth in the national park system was part of the overall federal government expansion under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Hartzog funded much of the expansion in the national park system through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Created by congressional legislation in 1965, this fund utilized park use fees for land acquisition. The prospects for the expansion of Cowpens were bright under the Hartzog administration at the NPS. [11]

Between August 1967 and February 1968, alternatives for expanding Cowpens as called for in proposed congressional legislation were studied by an NPS team that included Moomaw and staff members from the Southeast Regional Office and the Office of Resource Planning. Historian Ed Bearss researched the battle and prepared troop movement maps. Using this information, the team conducted fieldwork and determined the lands necessary to preserve the battle site. The team's report recommended two options for expansion. The primary difference between the two plans was the acreage to be acquired785 acres versus 510 acres. Although both alternatives allowed for the protection of the battlefield and the development of interpretive facilities, only the larger acreage would provide space for recreational facilities. [12]

Following the initial NPS assessment report, the Office of Environmental Planning and Design completed a master plan for the proposed park between 1969 and 1970. The plan called for a park of 845 acres with an annual capacity of 1.8 million visitors. South Carolina State Highways 11 and 110 were to be relocated around the battlefield. The core area of 130 acres was to be restored to its battle-period landscape. Interpretation of the battle as a Revolutionary War turning point would begin in a visitor center with museum exhibits. The battlefield would be toured via a walking trail, an automobile loop road with several overlooks, and a bridle path. In recognition of the significant role of cavalry during the battle, the plan envisioned horseback riding along the bridle path with a horse rental concessioner on site. In addition, the plan included a living history farm with livestock of the eighteenth century. Further recreational and educational opportunities were to be provided at picnic and environmental study areas. Hartzog approved the master plan in June 1970. [13]

As part of the planning process, the NPS sponsored public meetings to allow citizens and organizations with economic, regulatory, or general interests in the proposal a chance to voice their support or opposition to the park expansion. A public hearing in November 1970 was followed by a petition drive against the proposal. Spearheaded by local resident J.A. Parris, the petition drive opposed the battlefield proposal "with the best interest of our community and churches in mind." [14] In a letter sent to Kings Mountain Superintendent Moomaw with the petition, Parris noted the presence of nearly ninety residences and a church in the project area along with community water district infrastructure. Writing to the regional director, Moomaw expressed his surprise at the petition since Parris and other signers had been present at the public hearing but said nothing. The petition effort failed to galvanize opposition, which remained limited. Not surprisingly, most local residents who opposed the expansion lived within or near the proposed boundary and faced the prospect of being uprooted. Another meeting at the Cherokee County Courthouse in August 1971 attracted two hundred people but no significant opposition. [15]

In the meantime, the Cowpens proposal was gaining support from local, state, and federal governmental entities. The Cherokee County Board of Commissioners unanimously voted to support an expansion of the park in October 1969. [16] Recognizing that "the Battle of Cowpens is now inadequately commemorated by a national military site consisting of only an acre and a half of land," [17] the South Carolina General Assembly passed resolutions in March 1967 and January 1968 in support of the expansion effort and Gettys's bill. In April 1969 the South Carolina State Highway Department approved the relocation of the two state highways, provided that the NPS would acquire the necessary rights-of-way on behalf of the state and cover the initial highway construction costs. Another endorsement was obtained in April 1968 from the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments, a federal board established to advise the secretary of the interior on additions or expansions to the national park system. These various approvals and endorsements increased the momentum leading up to the congressional process. [18]

The Congressional Process

Gettys's October 1967 House bill and Hollings's January 1968 Senate bill both died in committee. In 1969 Gettys again introduced the bill, and the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs held a hearing to consider it in May. During the hearing, Hartzog was questioned about the bill's lack of ceilings for the costs of the authorized acreage and for appropriations for the development of Cowpens. In addition, committee members questioned the inclusion of recreational facilities at a historical site, but Hartzog responded that the proposed recreational facilities were minor components of the overall plan. Committee members further noted that the Service supported the concept of the project but still withheld its formal recommendation for approval due to the lack of firm cost totals. The committee failed to recommend the project, perhaps due in large part to restrictions on the use of appropriations from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The funding situation subsequently improved with the easing of these restrictions. For the third time, Gettys introduced Cowpens legislation in the House as HR 2160 in early 1971; Hollings introduced companion legislation as Senate 1552. Supporters of the bill prepared for hearings before the House and Senate Committees on Interior and Insular Affairs in November 1971 and February 1972, respectively. Backers of the proposal now had to convince Congress that the significance of Cowpens warranted spending millions of dollars and displacing eighty-four residences and six businesses. [19]

Key figures in the effort to persuade Congress to pass the Cowpens legislation were Gaffney optometrist and former mayor J.N. Lipscomb and Sam P. Manning, a Spartanburg attorney and South Carolina state legislative representative. While growing up in Spartanburg, Manning developed an appreciation of Cowpens from his father's telling about the battle and the presence of the Morgan Monument. As a member of the South Carolina General Assembly, he took a keen interest in commemorating the Revolutionary War. Manning served as Vice Chairman of the South Carolina American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and sponsored the concurrent resolutions supporting the expansion of Cowpens. In addition, he spearheaded a fund-raising effort to purchase the William Ranney painting The Battle of Cowpens for display in the South Carolina State House. [20] Like other Cowpens supporters, Manning was motivated by the feeling that "Cowpens deserved national recognition, but somehow, it had been getting left out." [21] Having served in the General Assembly, Manning understood the political process and the importance of utilizing personal connections and other tactics to get congressmen to identify with an issue. [22]

Once Manning became aware of Gettys's bill, he offered his assistance in gaining additional support for the upcoming congressional hearings. Manning contacted influential individuals for statements of support concerning the Cowpens legislation. Several prominent native South Carolinians wrote letters in favor of the proposal, including Louis B. Wright, former director of the Folger Shakespeare Library; David Finley, former director of the National Gallery of Art; James R. Killian, former president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Charles H. Townes, winner of the Nobel Prize in physics for laser research; Benjamin E. Mayes, former president of Morehouse College; General William C. Westmoreland, chief of staff for the U.S. Army; and E. Smythe Gambrell, former president of the American Bar Association. At Manning's urging, South Carolina Governor John C. West requested and received letters of support from the governors of the five other states with troops at the Battle of Cowpens. In addition, Manning received support from local leaders, such as Spartanburg Mayor Robert L. Stoddard, Cowpens Mayor Gordon Henry, Chesnee Mayor Cliff Edwards, and Editor Hubert Hendrix of Spartanburg's The Herald-Journal. Historians supporting the legislation included Henry Steele Commanger, Admiral Samuel H. Morison, and Richard Morris. [23] As Manning later recalled, there "was a fantastic level of distinguished Americans that related to [Cowpens]." [24]

Manning also used his connections with both the Democratic chairman and the ranking Republican of the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee. Manning contacted Walker Benjamin Camp, a native of South Carolina who had spent his childhood near the Cowpens battleground. Camp had moved to California in 1917, had become an agricultural leader, and had been largely responsible for the growth of cotton cultivation in that state. Prior to the introduction of the Cowpens legislation, Camp served on the federal Water Resources Committee of the West. In fact, he co-chaired the committee with Wayne Aspinall, the Colorado congressman who would chair the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee at the time of the Cowpens hearing. Since Camp and Aspinall had developed a friendship, Camp contacted Aspinall to encourage him to support the expansion legislation. [25]

Manning's connection with the ranking Republican on the committee, John P. Saylor of Pennsylvania, was through South Carolina's poet laureate Archibald Rutledge. Saylor had attended Mercersburg Academy, a private boarding school in Pennsylvania, where he had known Rutledge as a teacher. Manning visited Rutledge before traveling to the November 1971 committee hearing in Washington. During the visit, Rutledge expressed his support for the Cowpens legislation, saying that "nothing in the world would please him more than the passage of this legislation." At the committee hearing, Saylor asked how Rutledge felt concerning the proposed development at Cowpens, and Manning was able to relay Rutledge's comments. [26]

In the Senate, the Cowpens bill had the backing of both South Carolina Senators Thurmond and Hollings as well as Mississippi Senator John Stennis, a powerful member of the body. Manning was able to gain Stennis's support thanks to a local newspaper article. According to the article, Stennis was descended from a Spartanburg area family that had participated in the Battle of Cowpens. In addition to the Stennis connection, Manning had met the last surviving pallbearer for West Virginia Senator Robert C. Byrd's mother at a Kings Mountain anniversary ceremony. Manning was able to use that connection to gain Byrd's support for the Cowpens legislation. [27]

Although the NPS had prepared preliminary field studies and plans to develop an expanded Cowpens, the Department of the Interior opposed passage of the legislation at hearings before the House and Senate Committees on Interior and Insular Affairs. With various projects competing for the limited available funds, the department requested additional time to set priorities for park projects. At the direction of the secretary of the interior, Hartzog opposed passage of the Cowpens legislation. Ironically, Hartzog was a South Carolina native and had attended Wofford College in Spartanburg. [28]

Gettys, Manning, Chairman P. Bradley Morrah, Jr., of the South Carolina American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, and other Cowpens supporters appeared before the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs in November 1971 to provide information and testify in favor of HR 2160. Despite the Department of the Interior's objection, the December 1971 committee report recommended passage of HR 2160 as part of an omnibus bill, HR 10086, that dealt with appropriation ceilings and boundary changes for multiple national parks. In justifying immediate passage for the proposal, the report pointed out the years of NPS planning invested in the project. [29] The report further suggested that "the only real question involves the establishment of [funding] prioritiesa function which rests with the Congress and not the Executive Branch." [30] The omnibus bill passed the House in January 1972. [31]

|

| Figure 10: A circa 1960 view of Cowpens NBS showing the residences and agricultural fields that surrounded the site prior to its development as a full-scale national battlefield |

In February 1972 a hearing on HR 10086 was held before the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. In addition to concerns detailed in previous hearings, some final reservations were expressed by the committee with regard to the displacement of two elderly residents with long-time ties to the land that would become part of the national battlefield. However, Director Hartzog easily dispelled any fear by noting that, sadly, one was near death, and the other was willing to sell. A favorable committee report was then sent to and approved by the full Senate. Finally, President Richard Nixon signed HR 10086 into law on April 11, 1972. Cowpens became a national battlefield rather than a national battlefield site. The legislation authorized over five million dollars for acquisition of approximately 845 additional acres and park development. Cowpens could at last join Kings Mountain, Guilford Courthouse, and Yorktown as full-scale NPS battlefields commemorating the South's major Revolutionary War battles. [32]

Nearly a century had passed between the initial federal commemorative effort to construct the Morgan Monument in 1880 and the authorization of the national battlefield in 1972. Many factors helped delay the end result. In 1880 congressional funds provided to commemorate the battle were used to build a monument in Spartanburg, delaying interest in preserving the actual battlefield. Following World War I, patriotic enthusiasm for establishing military parks was so intense that Congress was overwhelmed by proposals. Cowpens lost out to stiff competition for limited funds. Later, when Congress authorized the War Department to establish a military park, it classified Cowpens as a low priority, mandating the acquisition of land through donation. Although another surge in park expansions took place after World War II, Cowpens lacked inherent landscape features to steal attention from other potential military park sites where such features existed. It took years of lobbying by local NSDAR chapters, community leaders, state politicians, and professional experts to produce the final national battlefield legislation. Lacking any substantial opposition, with mounting interest in bicentennial commemorations, park supporters finally achieved success by manipulating influential political contacts. As this long process came to a close, the Park Service accepted responsibility for developing the new national battlefield into a park worthy of the significance of the Battle of Cowpens.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/cowp/adhi/adhi3.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002