|

The Forest Service and The Civilian Conservation Corps: 1933-42

|

|

Chapter 13:

George Washington National Forest

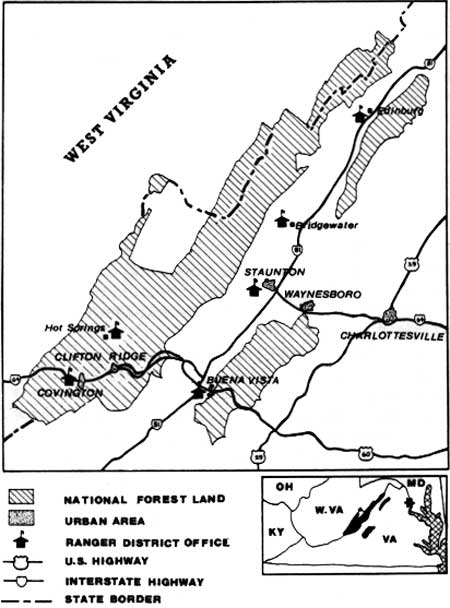

Today the George Washington National Forest includes more than 1 million acres in northwestern Virginia and a small part of eastern West Virginia. The George Washington has six ranger districts: Deerfield, Lee, Dry River, Pedlar, James River, and Warm Springs. The forest is divided into three noncontiguous sections, following the north-south direction of the Appalachian Mountain system.

The history of the George Washington National Forest begins in 1914 when five forest areas were acquired for national forest lands under the Weeks Law. These areas were the Massanutten, Natural Bridge, Potomac, Shenandoah, and White Top; they accounted for approximately 260,000 acres of Virginia lands. By 1918, the forest lands had been consolidated and were called the Shenandoah and Natural Bridge National Forests, with headquarters in Harrisonburg and Buena Vista, respectively. [1]

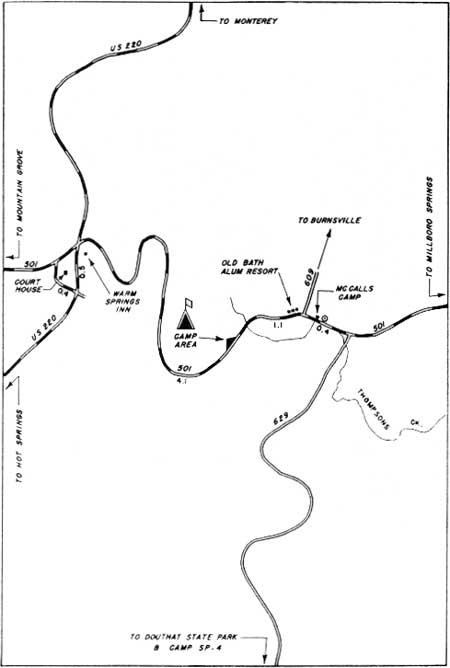

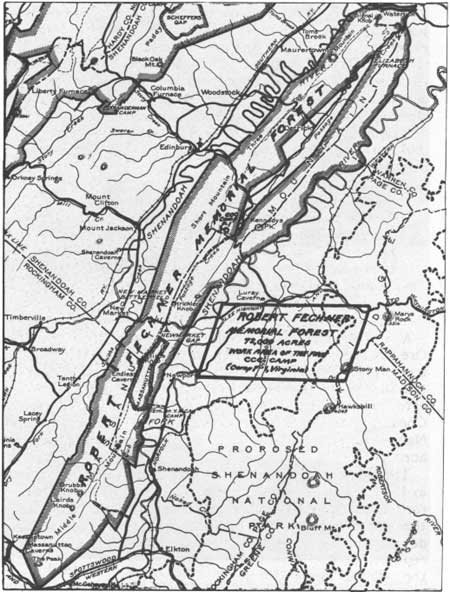

Over the next 15 years new national forest lands were added under the Weeks Law, including portions of the Monongahela and Unaka National Forests, administered in West Virginia and Tennessee. In 1932, the name of the Shenandoah National Forest was changed to George Washington. When the CCC began operating the next year, the George Washington National Forest had a gross acreage of 649,500, having just absorbed the Natural Bridge Forest. This included 272,684 acres of private lands, 6,641 acres of which had been approved for purchase under the Weeks Law (fig. 37). [2]

|

| Figure 37—George Washington National Forest, VA and WV. (Courtesy of Forest Supervisor's Office, George Washington National Forest, Harrisonburg, VA) |

On April 17, 1933, the first CCC camp in the country opened on the George Washington National Forest. This was Camp F-1, Camp Roosevelt, situated 9 miles east of Edinburg, VA. During the first enrollment period, nine more camps opened on the forest and continued operating through the winter. These were Camps F-2, Mt. Solon; F-3, West Augusta; F-4, Fulks Run; F-8, Sherando; F-9, Vesuvius; F-10, Snowden; F-11, Goshen; F-13, Natural Bridge; and F-15, Wolf Gap. In August 1935, Camps F-16, Woodson, and F-18, Oronoco, began operation. In April 1938, F-25, Bath-Alum, opened with enrollees from the Woodson Camp. A 14th camp, F-24, Allegheny, also operated briefly in the George Washington Forest.

Located close to large urban populations, the George Washington's historic and environmental qualities have made it a popular visiting place. The CCC spent much time developing recreation areas that have allowed visitors to take advantage of the forest without disturbing other resource areas.

Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees on the George Washington also contributed to the development of the forest through forest improvement work to establish better tree growth. Constructing more accessible routes and communication to isolated areas assisted with this work and with forest fire protection. Few administration buildings were built, as the ranger districts were centered in nearby towns. Nearly all CCC-built structures on the George Washington are recreational. A few buildings left from the camps are still in use by the Forest Service as utility or storage buildings.

Recollections of James R. Wilkins

James R. Wilkins, a longtime resident of Winchester, VA, worked for the USDA Forest Service in 1932 (fig. 38). He began as a foreman in a Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) program, primarily doing road surveys. When the CCC was started, Wilkins began helping the Forest Service prepare for the camps. Later he became a camp superintendent, his two main camps being Camp Wolf Gap and Camp Roosevelt. He was 23 years old when he began supervising camps, younger than many of the enrollees. [3]

|

| Figure 38-James R. Wilkins, Winchester, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

Wilkins noted that hiring local men to act as subforemen occurred at the request of the project superintendents. Locally enrolled or "experienced" men (LEM's) did not enlist in the same way as the enrollees; they were recruited personally by men like Wilkins. According to Wilkins, "We'd just pick out men who had skills that we wanted, timber skills or mountain skills, wouldn't get lost, and knew how to do timber cruising and everything of that sort." Sixteen LEM's were assigned to each camp; many were used as foremen in the side camps.

Side camps in the George Washington consisted of 20 to 40 men working in an isolated area. Timber cruising and surveys were their usual projects. In the summer, enrollees would live in tents, and in winter, "shanty" barracks were constructed. If buildings already existed at the site, they were put to use. An old lumber camp at Delbert's Hole, WV, became one side camp.

Wilkins remembers the main camps started as tent camps, but gradually old Army plans were used to build barracks. Modifications for CCC use occurred over time. Local labor and materials were used almost exclusively, although enrollee labor supplemented when necessary. From 250 to 300 men could be housed in a camp. Side camps would absorb some of the men. Numbers fluctuated as men entered and left the CCC.

Enrollees came from the coal regions of Pennsylvania and the big Eastern cities such as Washington, DC, Norfolk, and Richmond. About one-third were Appalachian "mountain people," and the other two-thirds were from cities. Wilkins observed that frequently the mountain boys were illiterate and would be embarrassed to go to night classes with the city boys who were better educated. On the other hand, the city boys had never worked and many only knew the block where they had lived. According to Wilkins, nearly all the camp personnel were involved in the education program and taught either vocational or academic subjects. Camp response to the program was positive.

Punishments for rule infractions varied in the camps. If a transgressing enrollee didn't change his behavior after an initial informal talk with the superintendent, he might be put into the "8-ball gang," the dirtiest work in camp, such as digging ditches or latrines. KP duty was considered equally undesirable. In serious cases, an unofficial "summary court martial" might be called. Fines came out of the man's pay, but not from the money designated to be sent home. Confinement to the barracks or camp was also used as a discipline measure.

There was recreation at the camps. Saturday night entertainment might be a religious group, mountain or country music groups, or some other activity in the recreation hall. The camps usually had a basic library, a place to write, and a radio. Most interactions between camps were athletic competitions, but once or twice annually contests might be held in activities such as woodchopping or truck driving.

Wilkins recalled firefighting as a major task for the CCC camps and one of the rare times when blacks and whites were integrated. Being "fire boss" was one of his toughest jobs. One fire burned between 1,500 and 1,600 acres before it was controlled. Other work projects undertaken by the CCC in his areas were construction of the Fort Valley Road, the Edinburg to Luray road, many small service roads, bridges, telephone lines, lookouts, and the Elizabeth Furnace Camp, and timber surveying and cruising.

Wilkins suggested that one benefit to local people of the CCC's roadbuilding projects was the opening up of isolated mountain areas: "Once we built roads, they started going to high school, and in a few years you couldn't tell the mountain people from the valley people. Before you could pick 'em out of the crowd like a sore thumb." At the same time, he says, the Federal government began buying the back lands, and Appalachian people moved into the valleys.

The Forest Service educated the mountain people about fire prevention by having CCC enrollees drive movie trucks around and show films in schools and churches. Many of the people had never seen movies before. In Wilkins' mind, it was a successful project.

Wilkins considers the CCC a highly worthwhile program: "The government got more for their money on the CCC program than on any program they ever had before or since." In his later experiences as an Air Force commander, he found that "most of my keymen were former CCC men," because "they'd had some training, they had discipline, plus they had been trained to operate bulldozers, jackhammers, to use dynamite; they'd been taught to do things and they knew what to do." Wilkins further noted that most of the men who stayed 12 months or longer in the CCC learned how to adapt to many situations and therefore tended to have been successful later in life. "So it wasn't only a case of getting a lot of work done. It was a case of saving the young population that had become drifters, getting them back into some kind of productive work and some self-respect for themselves."

Camp Roosevelt, F-1

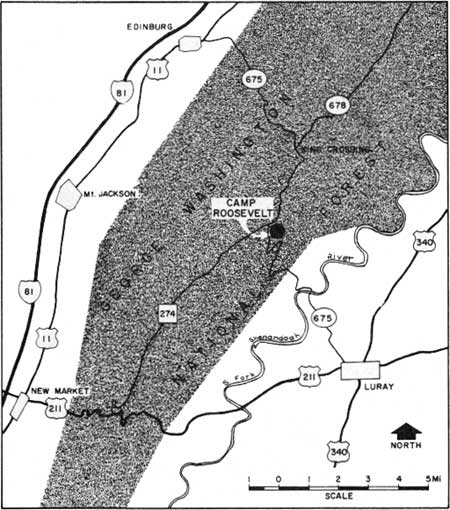

On April 17, 1933, eight buses and three moving vans left Fort Washington, MD, to establish the first CCC camp in Virginia's Massanutten Mountains (fig. 39). Located on Mt. Kennedy, 9 miles southeast of Edinburg, the 13-acre camp opened under the command of Captain Leo Donovan of the infantry reserve. Second in command, and construction officer, was Second Lieutenant William F. Train. [4]

|

| Figure 39—Camp Roosevelt, F-1, VA. (Courtesy of Supervisor's Office, George Washington National Forest, Harrisonburg, VA) |

Train shared his memories of his first few days at Camp Roosevelt at the dedication of the camp's recreation area in 1965:

First we had trouble finding the place. . . . Then the second day it turned into a sea of mud. We had been ordered to build the camp in a week, and we made considerable progress despite the weather because we were told that President Roosevelt was going to make a personal inspection. He never showed up, but we named it Camp Roosevelt anyway. [5]

The President did get there later that summer.

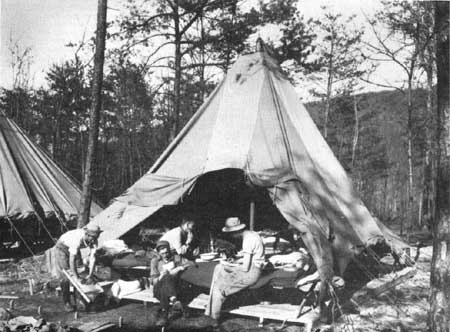

At first the enrollees lived in eight-man tents. It was several months before permanent buildings were constructed. Lieutenant Train designed the camp buildings and layout. Using CCC labor and locally hired carpenters, he directed the camp's construction. [6] Floors for the tents, a mess hall and kitchen, a headquarters building, recreation room, tool house, and a hospital tent were set up. A swimming pool was made by constructing a dam across Passage Creek. The frame recreation building was equipped with a piano, chess games, checkers, and library. Kerosene lamps provided the camp's first lighting. [7]

Photographs taken when Camp Roosevelt was first established show the original tents and cleared grounds (figs. 40-43). Later documents indicate rigid construction (portable buildings had not yet been introduced) and carefully landscaped grounds. The buildings were battened, covered with tar paper, and had stone foundations and chimneys. Windows were six-over-six, double-hung sash windows. A stone drinking fountain was located in the camp's center along with the flagpole. Gravel walks were bordered with small rocks and trees, and plantings were spaced here and there, retaining some of the natural setting. Twenty-seven buildings were eventually built and occupied at the camp.

|

| Figure 40—First men to arrive at Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest. (National Archives, Pictorial Record of Establishment of Camp Roosevelt) |

|

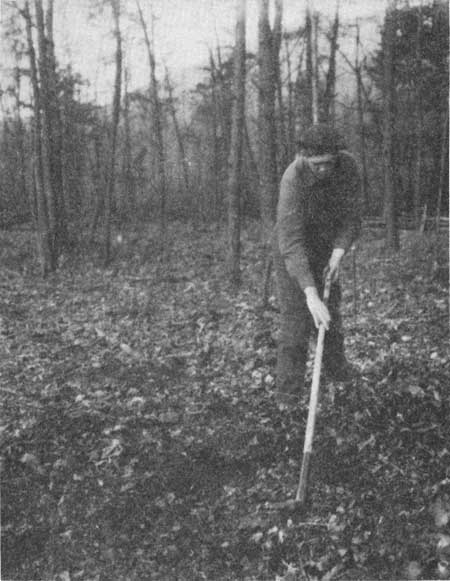

| Figure 41—CCC men raking the ground where tents are to go up, Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest. (National Archives, Pictorial Record of Establishment of Camp Roosevelt) |

|

| Figure 42—View of men in their tent, Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest. (National Archives, Pictorial Record of Establishment of Camp Roosevelt) |

|

| Figure 43—Cooks preparing dinner at Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest. Cookhouse in background under construction. (National Archives, Pictorial Record of Establishment of Camp Roosevelt) |

On May 1, 1933, 125 enrollees left camp to work on forestry projects in the George Washington National Forest. [8] Twenty days later the chairman of Virginia's Commission of Conservation and Development, William Carson, wrote to President Roosevelt that the Nation's first CCC enrollees had been transformed from a "slovenly bunch" to a "fine, healthy-looking lot of young fellows." [9]

At the end of February 1935, Camp Roosevelt's commander, in charge of Company 322, was Captain P.O. Tucker. The camp was reportedly "under good management and control." There were 180 enrollees in camp from Virginia and Washington, DC. One hundred and fifty worked on forest projects and 28 were detailed to camp for fire guard and wood details. Sixteen local, experienced men assisted Project Supervisor L.V. Kline in supervising work crews. Initial projects were road and concrete bridge construction and roadside improvement cutting. [10]

Camp buildings were reported in good condition in 1935. Water was secured from a driven well. Latrines were of the pit type. Waste water from the kitchen and showers was filtered and drained into a nearby stream. Food supplies were obtained locally and through the quartermaster at Fort Meade. [11]

In August 1936, Company 322 was commanded by Captain Joseph W. Koch. James R. Wilkins replaced Kline as project supervisor. The company retained 150 enrollees. Camp conditions and company morale were said to be good. [12]

One hundred and sixteen enrollees from Pennsylvania and Virginia were living at Camp Roosevelt in December 1937. First Lieutenant Robert C. Mali was the new commander. Under Wilkins' supervision, projects included truck trail construction and surfacing, campground improvements, roadside seeding and planting, tree planting, fish stocking, and fire hazard reduction. [13]

Except for the 10-seat pit latrine, which was considered inadequate for the company's anticipated strength of 200 men, Inspector Patrick King reported the camp to be in exceptionally good condition, including human relations. [14]

In June 1938, Camp Roosevelt was under the command of Second Lieutenant John G. Plunkett and Superintendent Wilkins. One hundred and forty-nine enrollees belonged to Company 322, and work projects remained essentially the same. Authorization for construction of a new educational building had been made, but the project had not yet started. Bad weather and minor accidents had kept enrollees from working during the week and forced them to put in extra time on Saturdays. [15]

A January 1939 inspection report stated "commercial light" (electricity) had been brought to Camp Roosevelt. Numerous improvements had been made at the camp. Barracks had been painted, roofs retarred, floors replaced, plywood placed on walls, and wall lockers installed. The educational building was completed, and infirmary improvements included a shower and isolation ward. Recommended improvements called for a new scullery floor, supply storage building, truck garages, a new septic tank latrine, and recreation hall. [16] Recent closure of a 4-year-old side camp had resulted in an influx of enrollees into the camp. Prior to that time an extra barracks had been used as a makeshift recreation hall. Outside recreational opportunities included baseball, badminton, tennis, and swimming. [17]

Camp Roosevelt was constantly occupied until it closed in 1942 (fig. 44). Building alterations went on constantly during these years. By 1940, three truck sheds had been completed (fig. 45). In 1941, additions to the garage and oil house were made. [18]

|

| Figure 44—Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest. (National Archives 35-G-432) |

|

| Figure 45—Erecting a portable prefab building, July 26, 1940. (National Archives 35-G-523) |

On November 16, 1939, a recent deserter from Camp Roosevelt wrote to CCC Director Robert Fechner regarding his reasons for leaving the camp. According to his letter, 15 men had left the camp in 1 month. Reasons cited for the desertions focused on unsanitary conditions and poor quality food. Petty thievery and unnecessary fines imposed on enrollees were also mentioned. [19]

Although no immediate investigation into the problems appears to have been made, an inspection in October 1940 noted bad conditions in the mess hall and kitchen. It also indicated that 84 men had deserted camp in a year, and another 18 had been dishonorably discharged for other reasons. Fully 2,574 man-days were lost over a 3-month period due to sickness; 1,390 to special details; 902 to detached service; and 282 to bad weather. [20]

Among Camp Roosevelt's major construction projects were the Fort Valley Road, an 11-mile road "constructed primarily as an intercommunity, protection and utilization road," and the Crisman Hollow Road. [21] Additional work involved the experimental underplanting of 55 acres of white and shortleaf pines to discourage undesirable growth; thinnings of oak trees were made into fuelwood. Roadside stabilization projects using cotton netting, stream gauging of water runoff, and experimental wildlife feeding projects were also undertaken. Deer, turkey, and grouse were some of the animals benefiting from the latter program. [22] Recreation areas built or developed by Camp Roosevelt were Little Fort Picnic Area, New Market Gap, Elizabeth Furnace, Woodstock Tower, and Powell's Fort Organization Camp. There is some indication that the Woodstock Tower project was finished by a different camp, but which one is undetermined. [23] Camp Roosevelt also constructed the Edinburg Equipment Depot. [24]

Charles Mullens' Recollections of Camp Roosevelt

Charles Mullens was living in Alberene, VA, when he joined the CCC in 1934. [25] He signed up at the welfare office in Charlottesville and from there went to Fort Monroe for shots and other camp preparations. From Fort Monroe he was sent to Camp Roosevelt by train to Edinburg and on an army truck to the camp.

You felt kind of lonesome when you got over there in the mountains, but it so happened I knew three boys there who were from my home community. It took awhile to get accustomed and used to it, but the longer you stayed the better you liked it. [26]

Mullens stayed for 6 years, first as an enrollee and later as an LEM.

When Mullens reached Camp Roosevelt, the five barracks were already built. The camp could hold 250 men at full capacity, but the number fluctuated as men came and went. A typical day started with breakfast around 6:00 or 6:30. Barracks leaders would get their men ready and march them to the mess halls. The men carried their mess kits with them and were served on a first-come, first-served basis. After breakfast they washed their kits in a tank of hot water and went back to their barracks to straighten things up and prepare for work. During the day, Mullens was a truck foreman. He recalled:

They would send you across the road to the Forest Service and they would issue the tools for you to take, and tell you what truck to get on, what crew to go on. . . . There'd be a telephone crew, road crew that you'd slope the banks. . . . On road crew you had a mound of shale we'd beat up to make the roads . . . go to the quarries, get the shale out, and some of the men would have to . . . blast the rock . . . and you shovel it on a truck, and they'd take you to spray it on the road. [27]

Hot meals were trucked to enrollees working outside the camp. Meals were all prepared by enrollee cooks. At the end of the workday, the men would march to supper, stopping on the way for flag salute and mail call. After dinner there was a choice of recreational and educational activities. Two or three nights a week trucks would take enrollees to town.

Mullens remembers that work projects undertaken by Camp Roosevelt included firefighting, recreation area development, and construction of the Woodstock Tower. Mullens recalls the camp's participation in bringing deer back into the Shenandoah Valley. Deer were hauled in trucks from Pennsylvania and let loose in the Virginia mountains. [28]

Mullens felt the communities nearby were glad to have the camp there, mostly because of the economic benefits it brought. Community relations were improved further through competitive athletics between the towns and Camp Roosevelt. Many enrollees also participated in local church activities. It was through the Edinburg church that Mullens met his future wife. Most of the camp's supplies were obtained locally, and local labor brought in to do any major building work.

Mullens feels that being in the CCC taught him discipline, a quality he needed later in the army. It also taught him skills, such as using a saw and cutting wood, and how to get along with different kinds of people. Some time after Camp Roosevelt closed, the buildings were torn down and sold publicly. The water tanks and pump were cleaned up and used when the new recreation area was built over the old camp site.

Mullens married and settled in Edinburg, as did many other enrollees from Camp Roosevelt. He was instrumental in getting the Camp Roosevelt Recreation Area built and annually organizes an alumni reunion there.

Surviving Structures

The following accomplishments of Camp Roosevelt are still in use by the general public.

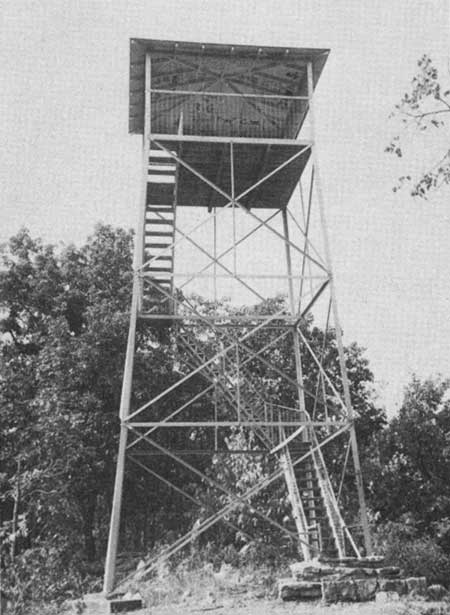

Woodstock Tower—The Woodstock Tower is a steel observation tower overlooking the Shenandoah Valley from Powell Mountain, east of Woodstock, VA (fig. 46). Construction of the tower was for recreational rather than fire protection purposes and was done as a "cooperative venture between the citizens of Woodstock and the CCC." [29]

|

| Figure 46—Woodstock Tower, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

Entrance to the Woodstock Observation Tower is by a 1/4-mile walk up stone steps laid by the CCC. The tower has a wooden roof and stairs. [30]

New Market Gap Campground—The New Market Gap Campground was the smaller of two campgrounds built by enrollees from Camp Roosevelt. [31] It is located south of the camp and west of the town of New Market in Lee Ranger District. The campground has one 20- by 20-foot picnic shelter, campsites, toilets, bumper logs, fire pits, and a registration booth. The original landscape plan called for chestnut oak, red maple, flowering dogwood, and a variety of shrubs. Many are still in evidence. The campground was completed in 1937.

The picnic shelter at New Market Gap (fig. 47) is constructed of peeled logs, 12 inches in diameter. Logs with a 6-inch diameter were used for corner bracing at each of the four corners and are belted to the posts and plate with 10-inch and 12-inch belts. The roof is hipped and supported by eight peeled-log posts.

|

| Figure 47—Picnic shelter, New Market Gap, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

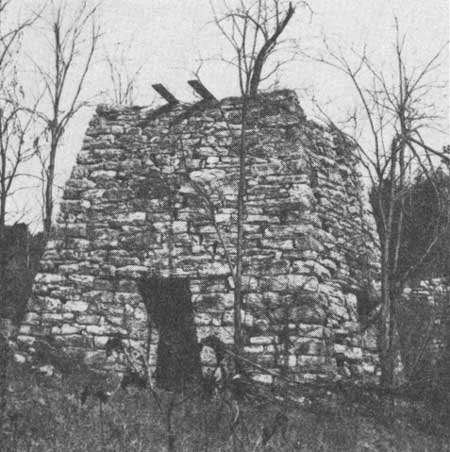

Elizabeth Furnace Campground—The Elizabeth Furnace Campground is located southeast of Strasburg, VA, on the Lee Road. It is the larger of the two campgrounds built by Camp F-11. [32] This campground was named after the iron ore furnaces built there in the early 1800's. Remains of these furnaces are still found scattered throughout the area (fig. 48). Rather than dismantle the unused furnaces, CCC builders recognized their historic value and named recreation sites after them. Like the New Market Gap Campground, the Elizabeth Furnace Campground was completed in 1937.

|

| Figure 48—Catherine Furnace, George Washington National Forest, VA. (National Archives 35-G-432) |

Elizabeth Furnace is similar in plan to New Market Gap, with two picnic shelters, campsites, a caretaker's residence, and larger grounds. A landscape plan was also developed here and included an even greater variety of trees and shrubs. According to a 1940 report of F-11's work projects, the Elizabeth Furnace area was partially developed prior to 1933 and used extensively by the public. The CCC "redesigned and reconstructed" the recreation area to accommodate greater use with less environmental impact. [33]

In preparing the grounds, CCC enrollees in 1936 dismantled one historical building at the site. Prior to removing the building, enrollees made sketches and took photographs, an unusual and early instance of recording and documenting a historic building. Many of the interior details were numbered for later restoration purposes. Samples of clapboard, shingles, hinges, door latches, and handwrought nails were saved from the building.

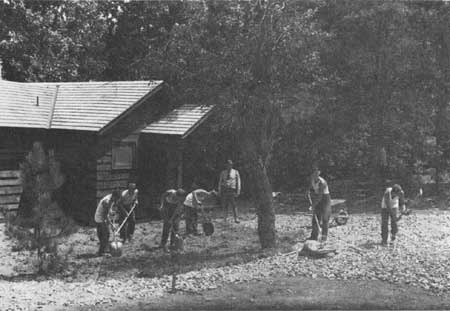

Powell's Fort Organization Camp—Powell's Fort Organization Camp is located in Little Fort Valley south of Strasburg, VA (fig. 49). This large organization camp includes two meadows, a baseball field, swimming pool, outdoor theater, bow and arrow field, and numerous buildings including kitchen, mess hall, barracks, toilets, shower, counselors' cabins, concession stand, and picnic shelter. [34] The camp was built as a recreation area for the underprivileged and originally was equipped to accommodate 96 campers and 16 staff members. [35]

|

| Figure 49—Camp Roosevelt CCC enrollees landscaping at Powell's Fort Organization Camp. (National Archives 35-G-637) |

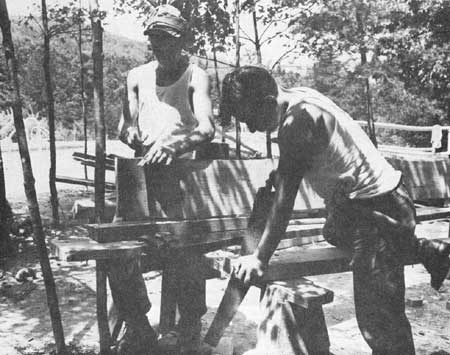

In 1937, the wavy-edge siding known as waney-edge was required for all buildings in the George Washington National Forest. A memo from the supervisor's office stated:

Another change in structural plans now effective is the substitution of wavy or wavy-edged siding for the existing standard of board or log siding. The pleasing effect of wavy-edged siding is obtained by leaving the exposed edge natural with the bark removed. Long waves and occasional knots are desired. [36]

Siding was to be made of white pine, and Camp Roosevelt was assigned to make, replace, and stock the new siding. All the Powell's Fort buildings have wavy-edge siding and are wood frame buildings with gable roofs, including the picnic shelter (fig. 50).

|

| Figure 50—Camp Roosevelt CCC enrollees making waney-edge siding for Powell's Fort campground. (National Archives 35-G-625) |

The Acceptable Building Plans manual shows a plan for an organization camp stylistically similar to Powell's Fort. The plan shows the buildings set on footings, but the material is unknown. The mess hall is shown as approximately 66 feet wide and 25 feet deep. The kitchen attached to the dining room is much longer than the one at Powell's Fort. The legend states: "Shingle roof. Waney edge siding. Chimney stonework roughly graduate from large stone to smaller ones above; surfaces battened about 4."

The Powell's Fort mess hall (fig. 51) is a rectangular building with a front porch. The porch is supported by two peeled logs, and its gable roof has board-and-batten siding. There are two front doors. Windows on the hall are six-over-six, double-hung sash, regularly spaced around the entire building. The foundation of the main building is concrete block that may have replaced an earlier foundation. The porch floor is shale or flagstone. The mess hall's interior has vertical wooden paneling, a large stone fireplace, and wooden floors.

|

| Figure 51—Mess Hall, Powell's Fort Organization Camp, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

The barracks at Powell's Fort are similar in plan to the mess hall illustrated in figure 51 (fig. 52). There are a screened-in front porch, similar type of windows, and a concrete block foundation. The concession building seen in figure 53 is a frame structure with a raised front porch or concession area. Showers are located in the back portion of an L-shape building. The picnic shelter has a gable roof, six peeled log posts, and braces.

|

| Figure 52—Barrack, Powell's Fort Organization Camp, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

|

| Figure 53—Concession stand, Powell's Fort Organization Camp, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

Mount Solon or North River Camp, F-2

Located near Mount Solon in Augusta County, VA, in the Dry River Ranger District, Camp F-2 was first occupied by Company 363 on May 31, 1933 (fig. 54). In February 1935, the 186-man company of white junior enrollees came from Virginia and Washington, DC. Captain A.S. Townsend of the Infantry Reserve was the camp commander. [37]

|

| Figure 54—Location of Mount Solon Camp, F-2, George Washington National Forest, VA. (National Archives 35-17, 897) |

Under the direction of Project Supervisor J.G. Moffatt, 147 enrollees and 15 locally enrolled men worked on the George Washington National Forest building roads and trails, recreation areas, and telephone lines, and performing forest cultural work and blister rust control. Another 26 enrollees remained in camp to work on camp maintenance projects. [38]

Investigator O.H. Kenlan reported in 1935 the camp buildings were in good condition and the camp in general showed improvements since its last inspection. Camp water was obtained from the town of Staunton and chemically treated before being used. A pit latrine served the camp, although plans to switch to a septic system had been made. Waste water was reportedly filtered and the overflow drained into a nearby creek. Garbage and refuse were burned. Food supplies were brought to the camp from Fort Monroe or bought locally. [39]

Between October 1, 1934, and February 27, 1935, 20 men received dishonorable discharges from Camp F-2 for desertion. No reason is cited, and morale is described as "good." A "mild" 2-month epidemic of influenza was reported as having affected 75 enrollees, but generally good health conditions prevailed otherwise. [40]

In August 1936, Company 363 called itself Tracy Camp and was comprised of 149 Virginia enrollees. Camp and project administration remained the same. Work projects were conducted within a 10-mile radius from camp and included road construction, reforestation, pest control, stream improvement, and telephone line construction and maintenance. In a 4-month period from April to August, no desertions occurred, and enrollee morale was described as "high." Further improvements throughout the camp were in progress. [41]

In January 1938, Tracy Camp had 153 men from Pennsylvania, Washington, DC, and Virginia. Ensign William Lennox of the naval reserve replaced Captain Townsend. Work projects continued to be of the same types as previous ones, with the addition of bridge construction; vista or other selective cutting for effect; reconnaissance and investigation; construction of levees, dikes, jetties, and groins; and public campground development. [42]

Inspector King notes:

Found this camp to be in rather good state, especially for a camp located so far in back mountain lands. Barracks in good state, as well as kitchen and mess hall. Recreation hall above average. Commanding officer able and seems concerned about giving a proper administration. [43]

The camp's water, gravity fed from the Staunton Reservoir, was tested daily and chlorinated; samples were tested twice monthly in Harrisonburg. Pigs were kept at the camp to consume garbage, because there were no local farmers to take it. [44]

On July 6, 1938, Company 363 left Mount Solon and was replaced by a 197-man veterans company, No. 3340. The camp name was changed to North River. Captain Alvin T. Wilson was the new company commander. J.G. Moffatt stayed on as project superintendent. [45]

Captain Wilson was a war veteran and a four-year veteran of the CCC. Due to a four-year limitation on holding command posts, he ended his first term of service in February 1938. Three months later he was recalled and assigned to Company 3340. [46]

Numerous improvements were made at the North River Camp by the new enrollees. Buildings were repainted; roofs repaired; the kitchen and scullery remodeled; plywood added to the barracks, mess hall, and recreation area; and a new education building nearly completed. A septic tank system replaced the previous pit latrine. Additional improvements were planned to be finished in 1939. [47]

In the 7 months since the new company had arrived at Mount Solon, 19 men had received dishonorable discharges for reasons other than desertion. Company morale was rated as excellent, although 3,751 man-days had been lost between November and January because of insufficient physical conditioning prior to arrival at the camp. Inappropriate winter clothing was cited also. Projects, when weather permitted, included road construction, surveys, and bridge building. [48]

Three months later, in March 1939, the North River Camp had decreased from 197 men to 175. All was reported to be in good order at that time, including the buildings that had been built in 1933. Camp activities were described as largely informal; for example, recreational and educational movies, pool, checkers, and card games. [49]

In October 1940, the North River Camp was still occupied by Company 3340. J.G. Plunkett had become the company commander, supervising the 184-man camp. Work under the direction of Moffatt was composed of lookout tower construction, truck trail construction, terrace outletting, and soil preparation. The camp was reported to be in "very satisfactory to excellent condition." [50] The camp remained open until September 2, 1941, when 19 of the camp buildings were transferred to Forest Service use. [51]

West Augusta, F-3

The West Augusta CCC Camp, F-3, was located near West Augusta in Augusta County, Virginia, within Deerfield Ranger District. The camp was first occupied on May 27, 1933, by 180 white junior enrollees. In January 1934, 198 Virginia-enrolled men were living in Camp F-3 under the command of Captain J.J.A. Devine. Since its opening, 61 men had been honorably discharged, 23 dishonorably discharged, and 34 men deserted. [52]

In 1933-34, an average of 160 enrollees worked daily on forestry work under the supervision of A.C. Dahl. Projects included road construction, timber stand improvement, tree planting, telephone line maintenance, horse trail construction, roadside improvement, and the building of fish dams. Five nonenrolled men were engaged to assist in forestry supervision. [53]

Within the camp, the general spirit of the enrollees was described by Inspector Kenlan as "excellent." Food supplies were procured locally and from Fort Myer. Community opinion was said to be favorable, and the men did not create trouble.

The West Augusta Camp, later called Ramsey's Draft, was vacated in May 1934. It remained empty until August 1935, when it was reoccupied. On May 27, 1936, Company 5449 from Fort Oglethorpe, GA, was brought in to occupy the camp. The company, made up of white junior enrollees from Georgia, Florida, and Tennessee, numbered about 151 after 3 months. Twelve locally enrolled men were also part of the camp. [54] Work projects were of the same kinds as previously undertaken.

In February 1937, Ramsey's Draft was occupied by 161 men from Company 5449. Captain Ernest C. Watson was the company commander, and R.G. Hopper was project supervisor. Crews worked within a 20-mile radius of the camp on timber stand improvement, trails and fire breaks, fire suppression, road and trail construction, and communication lines. Buildings and supplies were said to be in good condition with safety and work equipment adequate. [55] The camp closed on October 8, 1937. [56]

According to Ernest Kelley, retired Forest Service employee and former enrollee of Camp F-3, the Ramsey's Draft Camp did little work on recreation areas and only a small amount of roadbuilding. Road maintenance took a large portion of the camp's labor. Roadside pulloffs, including ones at Jennings Gap, Buckhorn, and on top of Shenandoah Mountain, were constructed, as well as 28.5 miles of roads. The roads have since been upgraded and maintained. Two new trails were built by the Ramsey's Draft Camp—Jerry's Run and Ramsey's Draft. [57]

Kelley says that Camp F-3's other projects included maintenance and occupation of fire towers on Elliots Knob, Wallace Peak, and Hardscrabble Knob. CCC crews built and maintained fire boxes, fire tools, and road and trail signs. Log dams were placed in many streams to catch sediment, control flooding, and improve fish habitat. [58]

In 1973, one building from the Ramsey's Draft Camp was being used for equipment storage by the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries. [59]

Fulks Run, F-4

The Fulks Run CCC Camp was originally occupied in October 1933. It was located approximately 3 miles west of the town of Fulks Run in Rockingham County, VA, within the Dry River Ranger District. The camp was made up of white junior enrollees. In 1934, it was abandoned, but by August 1936, the camp had been reoccupied twice by IV Corps Area companies.

The second IV Corps Area company at Camp F-4 was No. 5455. Captain E. Miller was the commander of the 141-man camp. Project supervisor was David G. Jennings, who directed work projects within a 20-mile radius of the camp. Road construction, forest improvement, timber survey, reforestation, and roadside clearing and maintenance were among the projects carried out in that area. Twelve locally enrolled men assisted on the jobs. [60]

In February 1937, Company 5455 still occupied the Fulks Run Camp. Parker S. Day was the new company commander. One hundred and thirty-two men lived in the camp. Work projects were similar, but truck and foot trail construction were also included. Camp water was obtained from a spring and deep well. Food supplies were procured locally, on contract, and from the New Cumberland, PA, CCC Depot. Company morale was described as "good." The camp's recreation hall was the only building requiring further improvements. [61] Fulks Run was officially closed on July 10, 1937. Twenty of its rigid-type buildings were transferred to Forest Service ownership. [62]

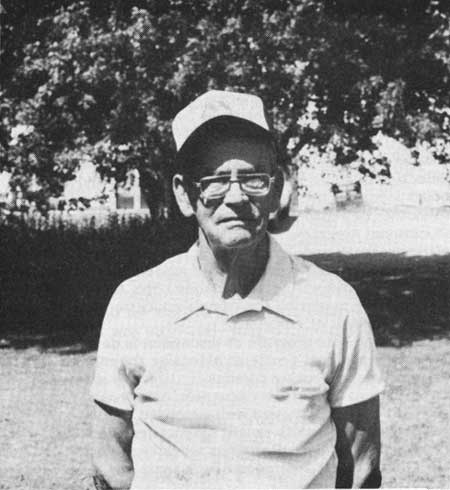

Millard Custer, a lifelong resident of Fulks Run, belonged to the Fulks Run Camp (fig. 55). [63] Work was scarce in 1933, so Custer went to Salem, VA, and joined CCC Company No. 374. He was 18 years old and newly out of high school.

|

| Figure 55—Millard Custer. Fulks Run, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

Custer was an enrollee for 14 months, moving to Fulks Run Camp by train from Fort Monroe in 1934. He estimates there were more than 200 men in the company then and many of them came from southern Virginia. Custer was pleased to get transferred to a camp so near his hometown.

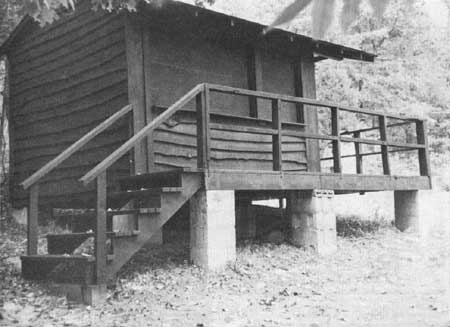

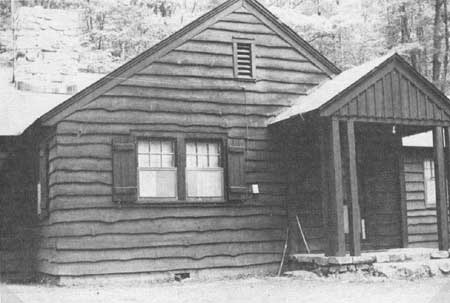

Upon arrival at Fulks Run, enrollees at first lived in tents. After about 3 months the company assisted with building barracks, using materials from a local lumber yard. Other camp buildings included a kitchen, mess hall, shop, infirmary, officers' quarters, tool shed, and recreation hall. The tool shed is the only extant building at the Fulks Run site (fig. 56). Custer's father built the recreation hall, which eventually contained pool tables for enrollee use. Work classes were held in the evenings. In addition to in-camp recreation, the Fulks Run enrollees often went to Edinburg on weekends where they frequently encountered Camp Roosevelt enrollees.

|

| Figure 56—Tool shed (north and west views), Fulks Run CCC campsite, Dry River Ranger District, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

Custer recalls working on forest improvement and roadbuilding. One of the camp's big projects was building a road from Fulks Run to the top of Fulks Mountain, and from there to Long Run Road. Local men were hired to teach and work with enrollees. One or two side camps were used to do work "back in the forest." Community reaction to the camp improved over time.

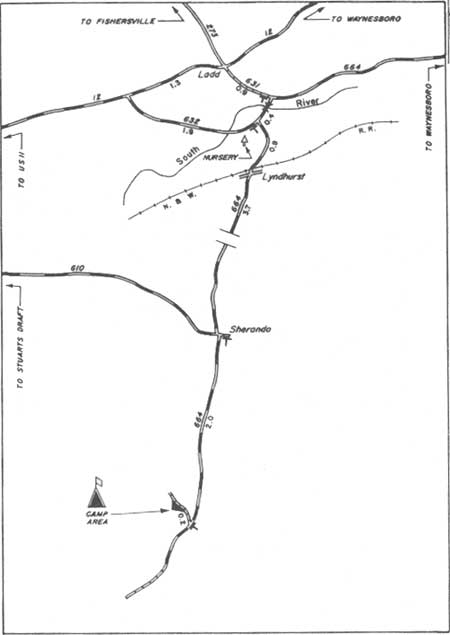

Camp Sherando, F-8

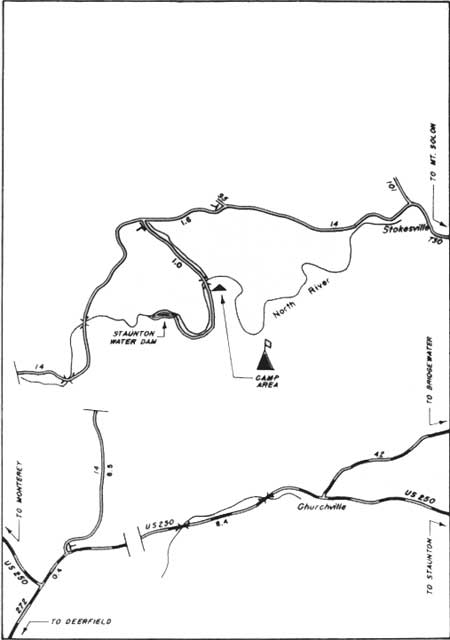

Camp Sherando was originally occupied on May 15, 1933, by Company No. 351, a company of white junior enrollees mostly from Virginia. The camp, F-8, was located south of Lyndhurst and Sherando, VA, in Augusta County within the Pedlar Ranger District (fig. 57). [64]

|

| Figure 57—Location of Camp Sherando, F-8, George Washington National Forest, VA. (National Archives 35-17, 897) |

In 1934, 152 enrollees lived at Camp Sherando under the command of Captain Richard Catlett. Carter T. Saunders was the project supervisor for the area. Approximately 90 percent of the work was road construction. [65]

On February 26, 1935, Inspector Charles Kenlan visited Camp Sherando noting it was then being called "Camp A. Willie Robertson." Company strength had grown to 187 men under the command of Captain Catlett and Mr. Saunders. Kenlan reported:

Camp shows marked improvement since last inspection. Is under very competent control and management... . Health, conduct, efficiency, and morale of enrollees improved since camp occupation. [66]

Building conditions at Sherando were rated as good to excellent, and particular improvements were noted in landscaping and drainage work in the camp area. The camp buildings were the rigid type. [67]

One hundred and sixty-one enrollees and fourteen locally enrolled men from the camp worked on a 10,000-acre section of the George Washington Forest. The main project was the construction of an earth-filled dam and 25-acre lake. Thirty thousand cubic yards of fill were used on the dam project. This construction was the start of the Sherando Lake Recreation Area. Other work projects were construction and maintenance of roads, trails, and telephone lines. [68]

From 1936 to 1938, Camp Sherando averaged 157 enrollees. Commander J.A. Betterly took over for Captain Catlett; work continued on the Sherando Lake Recreation Area. Projects in 1937 included the construction and maintenance of telephone lines, a water system, and truck trails; public campground development and maintenance; parking area construction; lake, stream, and pond development; channel and canal excavation; bank sloping; surveys; incinerator construction; and forest fire suppression. [69]

Inspector Ross Abare reported on March 23, 1939, that Company 351 had 188 enrollees. First Lieutenant H.H. Waller, Jr., was company commander; Saunders remained in charge of the Forest Service projects. According to Abare:

This camp is in excellent condition. Despite a rather unfavorable location the morale is excellent and the camp is well maintained. It is my opinion that the comparatively high discharge rate for desertions at this camp and at Moormans River is due in part to the out-of-the-way location of the two camps. [70]

Nonwork activities of enrollees at Sherando were described as volleyball, tennis, horseshoes, and various informal forms of recreation. A weekly entertainment program was established, often taking advantage of traveling entertainment shows. Twice a week enrollees were allowed to take trucks to nearby areas for outside activities. Protestant church services and Bible classes were held weekly, in addition to monthly services provided by a CCC chaplain and transportation of Catholic enrollees to town. [71] Ed Brooks and Harold Fitzgerald, residents of the local area, say the community was proud to have a CCC camp in its area, and relations between the two were very good. [72]

A variety of new projects were added to the camp's ongoing improvement of the Sherando Recreation Area. Crews did considerable amounts of work developing the Big Levels Game Refuge, such as clearing wooded acres and seeding them for wildlife maintenance, constructing horse and foot trails, checking and maintaining boundaries, and maintaining trap lines for predatory animals. An extension of the Sherando Dam spillway was completed, as was work on a camp utility building and general forest improvement. [73]

By October 1940, Camp Sherando housed 183 enrollees. Albert K. Brown was the new Company 351 commander, and Carter Saunders remained as project superintendent. Despite an increase of 37 dishonorable discharges in 12 months, the camp was reportedly in "very good to excellent" condition. [74]

Camp F-8, Sherando Lake, closed on July 18, 1941. [75] According to Tom Glass, a retired Forest Service employee familiar with the CCC's accomplishments on the Pedlar Ranger District, Camp F-8 was specifically responsible for the construction of parts of the following roads: Coal Road, Campbell Mountain Road, and Sherando Lake Road. Trails built by the camp were Torrey Ridge, Turkey Pen Ridge, Kennedy Ridge, Stoney Run, Bald Mountain, Cellar Mountain, and Appalachian. The camp maintained portions of the Blue Ridge Parkway, then called the Howardsville Pike. [76]

One building remains from Camp F-8 (fig. 58). [77] The garage or truck repair shop is a frame building of large proportions. Large garage doors are located on the front (north) side; a back door has been filled in. The two-story building is covered with shiplap siding, has a gable roof, and six-over-six, double-hung sash windows. A gable on the west side projects over a second-story door to hold a pulley. This door was probably used to hoist heavy equipment to the second floor. The garage was built with large wooden beams overlapped and braced together. The second floor is lined with wood or metal bracing to hold up the roof.

|

| Figure 58—Garage at Sherando Lake, built in 1933-34, that was formerly part of Sherando CCC camp and is now used as Forest Service equipment shed. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

Also left from the Sherando Camp are several concrete foundations and the camp's cement incinerator (fig. 59).

|

| Figure 59—Incinerator used by Camp F-8, Sherando Lake Recreation Area, Pedlar Ranger District, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

Sherando Lake Recreation Area

Camp F-8's major work project was the construction of the Sherando Lake Recreation Area, which opened to the public in 1937. The recreation area is currently operated by George Washington National Forest and used extensively. Evidence of the Sherando Camp's work is extensive throughout the 20-acre development. Buildings still in use include a combination bathhouse-picnic shelter, two picnic shelters, and an administration building. The dam, lake, water fountains, stonework, and roads are also in evidence. [78]

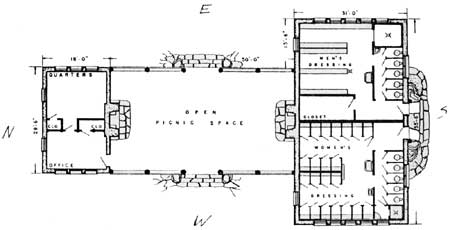

A plan for a combination bathhouse-picnic shelter appears in Acceptable Building Plans and is identical to the one at Sherando Lake fig. 60. The plan shows a T-shaped building with the top of the T being the central part of the men's and women's bathhouse. The longest part of the T is the picnic shelter area, with the end of the shelter area enclosed and used for office space and caretaker's quarters. At Sherando Lake, this area is used for a concession stand. [79]

|

| Figure 60—Forest camp bathhouse plan, Region 7. (From Forest Service, Division of Engineering, Acceptable Building Plans) |

The Sherando Lake building is covered with a random coursed, square rubble of quartzite, a metamorphosed sandstone. The stone is larger at the base and gets smaller as it rises. The technique gives the effect of the building leaning slightly inward. Dimensions of the bath house section of the structure are approximately 55 feet, 6 inches across the front and 31 feet from front to back. [80] There are two front entrances, side by side, with a gabled porch stoop constructed of logs and log brackets. The interior of the bathhouse is equipped with toilets, showers, and dressing stalls.

On the east and west ends of the bathhouse are a series of five windows (fig. 61). At the apex of the T-shape is a small cupola that serves as a vent.

|

| Figure 61—Bathhouse built by CCC at Sherando Lake Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

The picnic shelter portion of the building is approximately 68 feet across its east and west sides and 28 feet, 6 inches across the north end (fig. 62). The office end of the building is also stone. The picnic area is constructed of 12-inch-diameter log posts. There are 12 of these posts, each braced with 6-inch-long log braces on either side of the post. A log railing extends along both sides of the area, and the flooring is wood. The shelter has a gable roof with two gabled entrances on both the east and west sides. Two stone fireplaces are located at either end of the picnic area.

|

| Figure 62—Combination bathhouse and picnic shelter, Sherando Lake Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest. VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

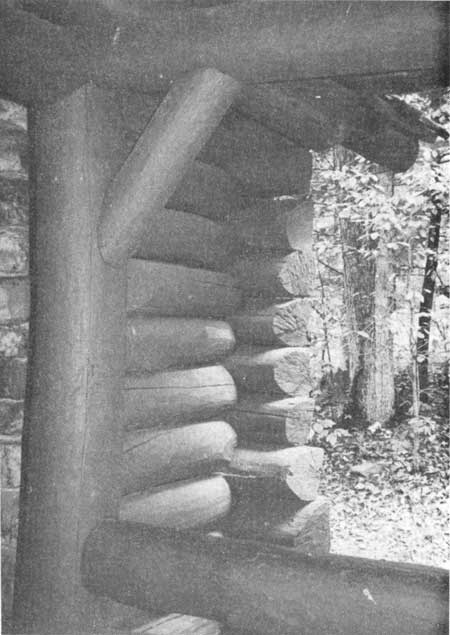

Sherando Lake has two other CCC-built picnic shelters. One has a kitchen, and the other does not (fig. 63). Plans for the kitchen shelter are found in Acceptable Building Plans. Its dimensions are approximately 38 feet across the front (north) and 35 feet from front to back. The kitchen is located at the back of the building and is approximately 18 by 14 feet. The walls of the kitchen are horizontal logs cut evenly at the ends and finished at the corners with a vertical log.

|

| Figure 63—Picnic shelter with kitchen, Sherando Lake Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

The shelter is rectangular and has openings on the three sides that are not attached to the kitchen. One side of the shelter has been filled in and is used as a bunkhouse for summer employees. Twenty-four 12-inch-diameter logs are used to support the shelter. The roof is gabled. A log rail, approximately 2 to 3 feet high, extends around all sides of the shelter. The floor is stone.

The second picnic shelter does not have a kitchen attached. It is characterized by a gable roof, stone floor, fireplace, log rail, and rustic picnic tables and benches. There are eight supporting log posts.

The Sherando Lake administration building is a rectangular structure with a residence at the west end and an office at the other (fig. 64). It is a wood frame building with waney-edge siding, six-over-six, double-hung sash windows, shutters, and eaveless ends. There is a front porch stoop with a stone floor. The structure has square posts and board-and-batten gable. The interior still contains some of the original rustic-style furniture.

|

| Figure 64—Administration building (front view). Sherando Lake Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

A common practice at the Sherando Recreation Area was to use copper flashing on all exposed beam ends to protect the wood from moisture. Posts or columns were made of white oak; beams were made of poplar. According to Doug Flint, a former enrollee at the recreation area, LEM's did the major construction work; enrollees were for general labor and mortar work.

Camp Vesuvius, F-9

Camp Vesuvius was established on May 31, 1933, south of Vesuvius, VA, in Rockbridge County within the Pedlar Ranger District. One hundred ninety-one enrollees made up the initial company. In January 1934, 194 men lived at the camp under the command of Captain W.L. Rice. The work project supervisor was W.B. Gallagher, Jr. Twenty-six men at F-9 were LEM's. [81]

About 145 men worked on forest crews out of Camp Vesuvius in 1934. Projects included stream improvement, roadside cleanup, timber stand improvement, bridge and road construction, telephone line construction, and the building of horse trails. Community relations and camp morale were reported to be very good. [82]

On July 18, 1935, Camp Vesuvius was occupied by Company 2345 from Tyler, PA, under Captain W.C. Mock's charge. At the end of September, a petition signed by 38 enrollees was presented at the camp, indicating those men would leave the camp on October 1 because the work project superintendent, Q.L. Umstead, was being too difficult.

An investigation into the men's reasons for leaving the camp and overall camp conditions was held on October 18, after the disgruntled men had left. The results of the investigation showed the project supervisor had resigned from a North Carolina camp because of similar complaints about his work, and the investigator decided the enrollees were somewhat justified in saying the superintendent had worked them too hard. Inspector Kenlan concluded, however, that neither Umstead nor Captain Mock could be held culpable for the situation. Umstead was issued a reprimand.

On January 16, 1936, Company 2345 was moved to Camp F-13 at Natural Bridge Station. Tom Glass, former employee on the Pedlar Ranger District, recalls that some of Camp Vesuvius' specific accomplishments were the construction of parts of Big Mary's Creek Road and South River Road. Trail construction included the Taylor Hollow, South Mountain, Whetstone Ridge, and Appalachian trails. The camp also installed a telephone line from Irish Creek to Buena Vista to provide "a more effective and expedient means of communication with various fire wardens throughout the district." [83]

Camp Snowden, F-10

On May 15, 1983, Camp Snowden was occupied by Company 354. It was a black company of 185 men. The camp was located in Snowden, VA, north of Lynchburg in Amherst County within Pedlar Ranger District. [84]

Civilian Conservation Corps Superintendent James R. Wilkins, now a Winchester businessman, recalls that the early days at Camp Snowden had their difficulties. He says that in the beginning of the CCC program many of the project superintendents were inexperienced political appointees, which created problems.

In January 1934, Company 354 was comprised of 196 men enrolled from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC. Captain R.D. Hazel was company commander and Carter T. Saunders was the work project supervisor. Since its establishment, the camp had lost 51 men to elopements and another 17 had been discharged for misconduct for refusal to work. [85]

An average of 155 men worked on projects involving forest improvements, roadbuilding, and trail and telephone line construction. Morale and community relations were described as being "very favorable." Camp water was taken from a tested and approved mountain spring. [86]

A special investigation was made at the end of January 1934 regarding nine men who had been dishonorably discharged from Camp F-10. The outcome of the investigation showed that one of the discharged enrollees had attempted to organize a "revolt" within the company:

It is also necessary to call attention to the fact that . . . the enrollee and 26 other men were from Philadelphia and Washington and were placed among men from Virginia and Georgia. A disturbing sentiment soon followed. [87]

It was also noted that 25 white men were enrolled at the camp and "while they work, mess, and live separately the plan has so far worked out advantageously." Camp management was ultimately judged competent and under control. [88]

In October 1934, a local newspaper reported that Company 354 was engaged in building a 24-mile road from Snowden to Buena Vista:

The road, constructed of crushed stone and sand clay, will provide access to woodcutting in the forest and serve as means of fire suppression. . . . In addition, it will also provide a scenic route for Sunday afternoon drives. [89]

Another important work project mentioned was the collection of some 600 bushels of pine cones and black locust seeds for the Tennessee Valley Authority. [90]

Another newspaper article described Camp Snowden's educational program. The entire company was involved in the program, and in less than a year 30 men had been taught to read and write. Classes also included commercial art, electric wiring, automobile care, and first aid. Classes were taught by the camp's educational advisor, other personnel, or enrollees.

An organized program of discussion is devoted to the personal problems affecting the men, problems affecting community life, the safety program, the forestry program, nature, and public health . . . two well-attended Sunday School Classes are taught by enrollees each Sunday morning. Religious services are conducted in the afternoon of the same day by a visiting minister. [91]

At the end of February 1935, Company 354 at Camp Snowden had 191 men. Administration and work projects remained the same as in 1934. [92] Mumps and venereal disease plagued the camp, and a special investigation of the camp's medical services was ordered. The investigating medical officer, C.G. Grazier, reported the mumps had been controlled by following quarantine and isolation regulations issued by the Virginia State Board of Health. The venereal disease epidemic, some 19 cases in a 1-year period, was being controlled through the establishment of a camp prophylaxis station and denial of "liberty parties" to Lynchburg. [93]

Camp Snowden closed on November 4, 1935. Nineteen of the camp's buildings were salvaged by the Forest Service. [94] Recollections of Camp Snowden's accomplishments by Forest Service retiree Tom Glass indicate that the camp built two 10-mile roads, one from Snowden to Pera, and one from Pera to Robinson Gap. Telephone lines were installed between Snowden and Naola, and Snowden and Bluff Mountain. At least eight trails were also constructed, including Dancing Creek, Terrapin Creek, Crushaw, Peavine, Otter Creek, Rocky Row Run, Belle Cove, and a section of the Appalachian Trail. [95]

Camp Goshen, F-11

Camp F-11 was located north of Goshen in Augusta County, VA, within Deerfield Ranger District. The camp was first occupied June 24, 1933, by Company 1334, composed of 164 black enrollees from Maryland, Virginia, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania. [96]

At the end of January 1934, 205 enrollees lived at Camp Goshen under the command of William M. Stokes, Jr. Work projects were directed by R.G. Hoffer and conducted on 50,000 acres of the George Washington National Forest. Timber stand improvement, trail construction, roadside cleanup, road and bridge construction, and seed collection were among the camp's projects. Several months after its establishment, 43 men had eloped and another 36 had been dishonorably discharged. Refusal to work was the most frequent reason for discharge. Two men were reportedly turned over to civil authorities for law violations. Despite the trouble and high desertion rate, morale was considered to be "excellent" and relations with the nearby community "very favorable." [97]

In April 1935, Camp F-11 had 125 black men under the same administration. Blister rust control and tree planting were added to the company's work projects. Fifteen LEM's assisted in the various forest improvement activities. The camp itself was described by Inspector Kenlan as being in good condition with further improvements being contemplated. [98]

At this time there appeared to be no evidence of the problems that led to a special investigation of the camp by Sub-District Commander Captain Riley E. McGarraugh. McGarraugh reported that on the weekend of May 15, a major disturbance had occurred at the camp. The incident was instigated by an enrollee of "rough character" who had been denied a discharge. In an effort to procure a discharge by other means, the enrollee and several friends started drinking alcohol and causing general commotion in the camp. Three men were arrested and discharged. The next day two more men were discharged. According to the investigator, the circumstances in camp leading up the explosive situation had been: (1) a few rough characters; (2) copies of the newspaper Afro-American, which allegedly emphasized "racial discrimination" and had a "bad" influence on the enrollees; (3) inclement weather during the weeks before, which required enrollees to work on Saturdays and forfeit weekend passes several weeks in a row. [99]

Camp "Rattlesnake," as it was informally called, closed on October 10, 1935. Twenty-three of its buildings were salvaged by the U.S. Army. Five were transferred to the USDA Forest Service. [100]

Arnold's Valley/Natural Bridge, F-13

The Arnold's Valley Camp was located near Natural Bridge Station in Rockbridge County, VA. Beginning in 1936, it was called Natural Bridge Camp. A company of 180 white veterans first occupied F-13 on July 13, 1933, under the command of Captain J.H. Patrick. Captain B.M. Venable took over on September 17, 1933. In October, 116 men from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia lived at the camp. [101]

Work projects in 1933 covered approximately 60,000 acres of George Washington National Forest's Gleenwood Division. Project Supervisor J.N. Jefferson directed an average of 62 enrollees daily on building and maintaining roads, cutting fire trails, improving timber stands, and maintaining telephone lines. [102]

In 1933, Arnold's Valley Camp appeared to have positive relations with the nearby community. Only one desertion was reported. Morale in general was described as being "very good." [103]

Four more commanders passed through F-13's administration before Captain C.U. Bauman took over Company 1395 on September 5, 1934. There were 167 men living in camp then. In November, Camp Inspector Charles Kenlan made a special report to the assistant director of the CCC describing problems with illicit moonshiners selling liquor to enrollees. Evidence against the bootleggers had been acquired by a Department of Justice agent masquerading as an enrollee. The case was brought to trial in Lynchburg. Problems associated with excessive drinking and lack of discipline subsequently improved. [104]

Recreation was provided through a variety of sources. A permanent library offered reading materials. Minstrel shows, movies, and band concerts were given, and a small, informal educational program was developed. Athletic events included baseball, horseshoes, and track and field competitions, both inside camp and with local teams. Transportation to religious services of various denominations was provided on a weekly basis. [105]

On January 16, 1936, what was now called the Natural Bridge Camp became occupied by Company 2345, previously stationed at Camp Vesuvius, F-9. Captain Milton C. Mock was still company commander, and J.N. Jefferson remained from the earlier company as project supervisor. One hundred and fifty-five men made up Company 2345, whose work projects were the construction of a dam and artificial lake, recreational development, road and trail construction, and forest improvement. Proximity to both the George Washington National Forest and Jefferson National Forest led to work being conducted in both areas. [106]

In 1937-38, the Natural Bridge Camp remained essentially unchanged. Frank C. Ware took over as project supervisor of work by the main camp crews as well as a small side camp established at Big Island. Additional projects included construction of several foot and vehicle bridges, shelters, and stock trails, fire prevention, campground development, fish and wildlife activities, and tree planting. [107]

By February 1939, F-13 had undergone several changes. The camp, now called Greenlee, housed 199 men under the command of Captain W.K. Andrews, Jr. Andrews received strong commendations from Inspector Ross Abare, who indicated that in the commander's short term in camp he had made numerous improvements and thereby put the camp into "generally excellent condition." Under the direction of Hampton W. Richardson, the camp's education advisor, the education program had greatly expanded. Formal classroom instruction and related vocational instruction were offered five nights a week and approximately half of the company enrolled. [108]

The educational program had made it possible for many enrollees to complete their formal elementary and high school education. It has helped greatly through the guidance program to focus the serious attention of many enrollees upon the problems of training for a job at which to make a living. [109]

In June 1940, CCC Director James J. McEntee received a letter from "Enrollees, Co. 2345, Camp 13, Natural Bridge Station, Virginia." The letter pointed out the current commander, Edwin Bennett, was treating enrollees like "slaves" rather than human beings. Furthermore, company funds were not used for company enjoyment. The situation was blamed for an increasing number of desertions. [110]

The administration considered this an interesting situation, because the same company, when stationed at Camp F-9, had protested against the "slave drive" project superintendent. Whether written by one enrollee or several, the letter does mention some of the issues that confronted CCC camps in general and southern camps in particular. The writer's first concern is why enrollees at F-13 were not "entitled to get transferred to other Corp Areas as the other enrollees do." [111] Enrollees looking for a free ticket across the country had become a problem in the corps. Undoubtedly, choosing which companies to send to western corps areas produced dissatisfaction among those who were looking for greater adventure but not chosen.

The letter also criticized F-13 for being more of a "military organization than a CCC camp." [112] The issue of how militaristic to make camp life became important during the early 1940's, as a result of the war in Europe. Any overt militarism was generally discouraged, but the decision was partially left to the judgment of the camp commander.

Company 2345 was replaced on August 1, 1940, by Company 3360, a company of 176 white junior enrollees. Work projects continued to be of the same nature as previously, and Commander Bennett remained as commander. Twenty-two men deserted Company 3360 in the first 3 months, which may have been symptomatic of the camp's administration, the deterioration of the corps in general, or the improvement of the country's economy and increase in private sector employment opportunities. [113] Camp F-13 closed in 1942. [114]

Camp Wolf Gap/Edinburg, F-15

Camp F-15 was occupied May 15, 1933, and called Camp Edinburg for its location just west of Edinburg, VA, in Shenandoah County within the Lee Ranger District. Seventy-two white junior enrollees were in the first company, No. 333, to occupy the camp. Men were enrolled from Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, DC. [115] By April 1934, 111 men lived at Camp Edinburg. Since its establishment 61 men had been dishonorably discharged, including 38 desertions and 3 misconducts. Some 145 men had been honorably discharged, including 84 accepting outside employment, 3 for physical disabilities, and 2 for venereal disease.

Camp commander was Captain LeRoy H. Barnard of the infantry reserve. James R. Wilkins was the work project supervisor. Approximately 80 enrollees and 16 LEM's worked on forest improvement and clearing fire hazards. In a year's time the efficiency of the men was reported to have improved 500 percent. Projects completed included construction of telephone lines, truck trails, a tool house, foot bridges, an office, and additional minor structures; maintenance of telephone lines, truck trails, and horse trails, roadside improvement; timber stand improvement; and the erection of many forest signs. [116]

By February 1935, Company 333 had grown to 184 enrollees and 15 LEM's. It was now a black camp. Captain Barnard remained as company commander and Wilkins as project supervisor. Similar projects were conducted. Discharges had decreased substantially, and the camp was reported to be in generally good condition. Investigator Charles Kenlan wrote the "camp is under good management and control. . . . An exceptionally low sick rate attributed to the fact that the men are fed hot food at all times and clothing is adequate." [117] Among roads constructed or maintained by F-15 in 1935 were Stultz Gap Road, Liberty-Lost River Road, Lower Cove Truck Trail, and Thornbottom Road. [118]

On August 5, 1936, Camp F-15 was referred to as Camp Wolf Gap and was located near Columbia Furnace, VA. One hundred and fifty-one black enrollees from Virginia and Washington, DC, occupied the camp, still under Captain Barnard's supervision. Wilkins had been replaced as project superintendent by B.J. Brockenbrough. Work projects had been expanded to include stream improvement and blister rust control. [119]

Food supplies came at first from Fort Myer, VA, and later from the New Cumberland depot in Pennsylvania. Water came from two deep wells at the camp.

The camp closed on October 11, 1937. At that time, 25 camp buildings were salvaged by the U.S. Army. [120]

Camp Woodson, F-16

Company No. 2355, consisting of 148 white junior enrollees from Pennsylvania and Virginia, originally occupied Camp Woodson in the Pedlar Ranger District on August 3, 1935. Located near the town of Woodson in Nelson County, Camp F-16 started out under the command of First Lieutenant M.F. Saul. A.D. Camden was the project supervisor. Projects covered a 17-mile radius from the camp and included road and trail construction, forest improvement, and construction and maintenance of communication lines. [121]

Inspector Charles Kenlan reported that, on a scale of poor to excellent, conditions at the camp were "good." The rating included the buildings, food supplies, equipment, and morale. Relations with the nearby community were also rated as good. Water supplies at the camp came from a mountain spring, and a pit latrine was utilized. Food supplies were obtained locally, on contract, and from the New Cumberland depot. [122]

By January 1938, Camp Woodson had 154 enrollees and a new commander, Lieutenant Robert R. Maynes.

Bernard Brockenbrough was the Forest Service project superintendent directing work projects on a large area of the George Washington National Forest. Among the camp's accomplishments in 1937 were vehicle bridge construction, truck trail construction and maintenance, foot trail construction, fire presuppression and prevention, roadside naturalization, fish stocking, traffic surveys, and planting and seeding food and cover for wildlife. One hundred and seven enrollees worked for Brockenbrough on the forest projects. A complete safety program was in effect at the camp, and approximately 14 vehicles were available for project use. [123]

On April 1, 1938, Company 2355 transferred to Camp Bath-Alum near Hot Springs, VA. Buildings from Camp Woodson were salvaged by the Forest Service and U.S. Army. [124]

Former Forest Service employee Tom Glass recalls that Camp F-16 was at one time called Al Hambre or the Big Piney River Camp for its location on the river. The camp helped construct the Big Piney River Road and installed telephone lines from Big Piney to Indian Creek and on to Rocky Mountain Tower. Trails constructed in the area were Cox's Creek, Shoe Creek, Pinnacle Ridge, England Ridge, Cardinal Ridge, Big Priest, and Little Piney. [125]

Camp Oronoco, F-18

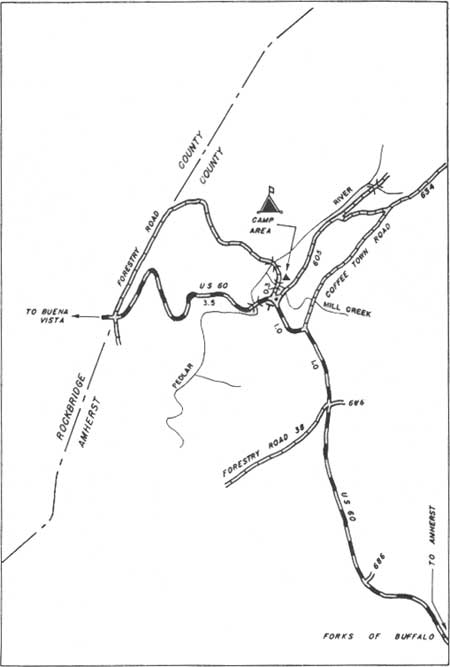

Camp Oronoco was originally occupied on August 4, 1935, by Company 2360. The camp was located near the town of Oronoco, VA, in Amherst County (fig. 65). [126] Company 2360 was composed of white junior enrollees, primarily from Pennsylvania and Virginia. At the end of December 1935, there were 166 enrollees in the company and 15 LEM's. Since the camp had opened, 24 men had been honorably discharged due to "pressing needs elsewhere," 11 for "administrative AWOL," and 10 for "other causes." In addition to Company Commander S.B. Over and Project Supervisor T.H. Glass, Jr., there were four reserve officers, six camp leaders, and eight forestry supervisors located in Camp Oronoco. Approximately 131 enrollees were workingon forest projects, and 25 men were on camp detail. [127]

|

| Figure 65—Location of Camp Oronoco, F-18, George Washington National Forest, VA. (National Archives 35-17, 897) |

According to Camp Inspector Charles Kenlan, crews from Camp Oronoco were working on 50,000 acres of the George Washington National Forest. Projects included road and telephone line construction and maintenance, timber stand improvement, fire hazard reduction, game refuge development, and fire tower construction. The Army provided 2 trucks and an ambulance, and the Forest Service provided 12 trucks, a tractor, a grader, and a compressor and jackhammer. Kenlan reported the "company operating under satisfactory control and camp progressing in proper order." A well-organized safety program seemed to have developed. [128]

The camp itself was of portable construction and had been completed at the end of September 1935. Kenlan reported that the condition of the buildings and the camp area was "good" with improvements in progress. [129] In a special letter to the CCC director, Kenlan indicated the "portable type camp does not have the weather resistance qualities of a permanent type camp." [130] Water for the camp was supplied from a drilled well that was tested regularly and chlorinated when necessary. A septic tank latrine was maintained, and kitchen and shower water was filtered and channeled into a nearby stream. [131]

In January 1938, Company 2360 still occupied Camp Oronoco. The 180-man company was made up of enrollees mainly from Pennsylvania and a small number from Virginia and Maryland. T.H. Glass was still project supervisor. Company Commander Over had been replaced by First Lieutenant James W. Lusby, an infantry reserve officer. Lusby had 2-1/2 years of service in the CCC. He took over as Oronoco's commander on March 22, 1937. [132]

Inspector Patrick King's remarks on Camp Oronoco's administration were:

Have no hesitation in giving stamp of approval to the general state of command existing at this camp as well as the condition of the buildings and the moral existing among the boys. . . . Present commander at this camp is of the type that is desirable for administration of a CCC camp. Understands needs of boys, understands how to handle them and how to manage care and improvement of camp buildings, as well as mess. [133]

Camp Oronoco's work projects remained essentially the same as in 1935, although they expanded to include fighting forest fires, field planting, fish stocking, surveying, and boundary marking. Some examples of work completed by the camp during 1937 were 110 man-days fighting forest fires, 6 miles of telephone line construction and 100 miles of maintenance, 3 miles of truck trail construction and 50 miles of maintenance, 80 miles of foot-trail maintenance, collection of 100 pounds of tree seeds, maintenance of 3 lookout towers, 10 miles of boundaries marked, 176 man-days of survey work, 25,400 fish stocked, 1,201 man-days of fire presuppression, and 112 man-days of fire prevention. [134]

Inspector King reported camp buildings remained in good condition and numerous improvements had occurred in a year's time. Among those improvements were the construction of a reading room, recreation hall, and classroom. Also noted was the betterment of the camp latrine and ground drainage and the installation of hot water in the camp hospital. Painting was scheduled for the barracks, kitchen, and mess hall, and a steam sterilizer for dishwashing had been ordered. [135]

Food supplies were obtained from three sources. Fresh vegetables and fruits came seasonally from the nearby towns of Lynchburg and Lexington. Meat was contracted through local suppliers. Canned foods were shipped from the New Cumberland CCC Depot. The inspector's reaction to the mess was highly favorable; he gave credit to experienced cooks and junior officers for the good menus and food. [136]

Relations between Oronoco camp enrollees and the local communities were said to be "favorable." Any problems were taken to the company commander for resolution "rather than make further trouble in town, with court records or the like." Few problems of this nature had been encountered. Recreation and athletics were provided in camp. Church services were provided either by a visiting Catholic priest or Army chaplain. Some enrollees went to town for services. [137]

In February 1939, few changes were reported at Camp Oronoco. Company 2360 had grown to a strength of 197 men. Inspector Ross Abare gave high ratings to the camp's buildings, mess, and morale, saying, "Although the buildings at this camp are of the portable type, the camp as a whole is superior to the average camp as I have seen them in this District." Lusby and Glass remained as company commander and superintendent respectively. [138]

Despite a relatively high desertion rate of 27 in 12 months, the camp received similar ratings in May 1940. Still under the same administration, the camp was reported in "generally excellent condition . . . well maintained and . . . well developed. Morale is excellent and the company has maintained a consistently high strength." An elaborate educational program with 38 subjects of instruction was administered by the camp educational advisor, Charles Edwards. Classes ranged from reading and writing to cooking, truck driving, house painting, typing, business law, carpentry, glee club, and safety. Of the 199 men in the company, 133 attended classes daily. A separate library was established for enrollees to use for studying or reading books and magazines. [139]

Camp Oronoco closed in 1942. Tom Glass recollects that Oronoco's accomplishments included construction of part of the Irish Creek Road. CCC crews also did improvement work on the Jordan Road and maintained the Long Mountain Road. The camp built a cabin on Rocky Mountain, now removed, and maintained the fire tower there. Telephone lines were installed from the Bluff Mountain Tower to Buena Vista, and trails constructed at Bald Mountain, Reservoir Hollow, Whites Gap, Cow Camp, Howard Mountain, Gardner Spring, and Bunker Hill. The camp also built and maintained a portion of the Appalachian Trail. [140]

Longdale Recreation Area

Located in the James River Ranger District east of Covington and Clifton Forge, VA, the Longdale Recreation Area consists of an artificial lake, beach, three bath houses, a water fountain, and a picnic shelter. Built after 1935, it remains unclear which CCC camp was responsible for constructing the area. Evidence strongly suggests that it was built by Company 379 of Camp F-24, whose main camp was located 2.2 miles east of Covington. Little information has been found on this camp. [141]

The picnic shelter at Longdale is similar in style, though smaller, to the shelter at Sherando Lake (fig. 66). The shelter is a rectangular peeled and painted log structure. There is a fireplace at the back. The shelter has a stone floor and shingled gable roof. The gable ends are filled with horizontal logs 12 inches in diameter with 6-inch-diameter braces (fig. 67). Based on similar plans in the Acceptable Building Plans manual, dimensions are approximately 34 feet across and 20 feet from front to back. Inside the shelter are rustic picnic tables, also built by the CCC.

|

| Figure 66—Picnic shelter, Longdale Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

|