|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 12:

GRAZING AND CAPITOL

REEF NATIONAL PARK: A HISTORIC STUDY (continued)

Grazing In And Around Capitol Reef Prior To

1937

Early Grazing Patterns In The Waterpocket Fold

Country

The first livestock ranchers in or close to what is now Capitol Reef arrived in the 1870s and 1880s. Due to the area's small population and its physical isolation, however, there are few outside accounts detailing ranching practices in the Waterpocket Fold country prior to the Taylor Grazing Act. [86]

In this rugged, varied land, ranchers were free to graze their herds between the high-elevation summer pastures, on mountainsides rising over 10,000 feet, and the surrounding labyrinth of desert canyons and mesas, which provided winter range. Those who came later, especially after the national forest permit system was established in the early 1900s, ranged their sheep and cattle on the still unrestricted deserts year-round.

The effects of this unrestricted and highly competitive grazing were noticed in the Waterpocket Fold country in the early 1900s. Nethella Griffin, a long-time Boulder resident and daughter of prominent rancher John King, described the situation then:

[It was a] period of struggle between cattlemen and sheepmen and among individuals for control of the range. Every year the country became worse overstocked until, beginning in 1902 there were several years of drought that naturally intensified the evil of overgrazing. Cattle died by hundreds....By 1905 the rich meadows on the mountain plateau had turned to dust beds. Sheep, bedded in the headwaters of the mountain streams and dying in the water ditches, so befouled them that ranchers' families could hardly get a decent drink of water. Cattle bones bleached on the dry benches and around mudholes and 'loco' patches, these poisonous weeds seeming to grow after other forage was dead and to attract starving animals with a false promise of food. [87]

The U.S. Forest Service arrived on the scene when Fishlake National Forest was established northwest of the present National Park Service boundary in 1897. Powell (later part of Dixie) National Forest, adjoining Capitol Reef to the west, was created in 1905. The first known figures for cattle and sheep grazing near Capitol Reef are the Powell National Forest numbers, which presumably cover the summer pastures of those who grazed the Waterpocket Fold areas in the winter. In 1909, the U.S. Forest Service issued permits for 67,000 sheep and 11,000 head of cattle. These numbers gradually rose to 75,000 sheep and 13,800 head of cattle 10 years later. [88]

According to a draft history of the Dixie National Forest, the early years of U.S. Forest Service jurisdiction were not easy:

From the time the National Forests were established Dixie Forest officers have worked long and hard to find out what was actually taking place on the ranges due to heavy grazing use. Vegetative changes were so very slow that it was always difficult to be sure whether the range was getting worse, holding its own, or in some cases getting better. Differences of opinion were nearly always present. Stockmen generally felt that the range was getting better. World War I brought demand for more meat and as a result permitted stock in 1917 reached the peak numbers on the Dixie Forests. Since that time there has been a sustained effort to reduce numbers. In most cases the productivity of the ranges fell faster than reduction of livestock numbers which resulted in cut after cut with no apparent improvement of the range as a result. Reductions down to 1/3 of the 1917 load were not uncommon. In spite of this there was no apparent upward trend of the range established. [89]

Geologist Herbert Gregory, who made extensive geographic and geologic surveys of southern Utah throughout the early 20th century, confirmed the findings of the forest service:

The pioneer settlers, with small herds and flocks, before the native vegetation had been disturbed, were surrounded by conditions usual for stock ranges. 'Good years' of the period ending in 1893 were followed by bad years, culminating in 1896, when 'about 50 percent of the range stock died of drought and starvation.' Increased rainfall combined with the extension of grazing area...brought more favorable conditions. Overstocking of the range in response to the increased values of cattle during the World War appears to have been the first step toward the present unfortunate state. [90]

This pattern of use likely was common in the areas adjacent to the forest service and the Escalante area as reported by Gregory. In that case, is safe to say that southern Utah was following the cycles of good and bad years determined by climate, economics, and range deterioration found throughout the rest of the West.

As discussed earlier, the small, sometimes cooperative herds that were first on the range in the 1870s were soon increased by local ranchers responding to competition. By the early 1890s, the livestock depression reached into the isolated canyon country and combined with drought to bring on the first range crisis. By the beginning of World War I, increased demand for livestock and a series of wet years once again brought larger herds of sheep and cows onto both the forest and lower desert ranges. Then, the post-war agricultural recession and a return to drier times throughout the 1920s left the range and the livestock owners in the worst shape yet.

Other accounts concur that the range in and around Capitol Reef was already severely damaged by the early 1930s. A West Henry Mountains range survey, completed by the Bureau of Land Management in 1963, provides a brief description of past grazing use on the east side of the Waterpocket Fold. [91]

According to this survey, there was no domestic livestock use prior to 1875-76. Then in the early 1900s, Willard and George Brinkerhoff, William Meeks, and Will Bowns brought large herds of cattle to the area. At about the same time, Bowns also introduced the first large herds of sheep. By 1914, according to the report, sheep began to replace cattle on the range, and by 1928 sheep had largely replaced the cattle. [92] The U.S. Forest Service permit system also played a significant role in pushing more woolgrowers onto the still unrestricted desert range for the entire year. [93]

The BLM survey also includes portions of a 1948 interview with Mr. and Mrs. George Durfey, who brought their family and sheep to Notom in 1919. [94] The interviewer, Range Conservationist Ben S. Markham, recorded the situation that existed when Durfey first arrived:

[T]he range was heavily loaded with stock. The Bowns ran seven big herds of sheep, averaging 2,500 to 3,000 head per herd. Mr. Durfee [sic] ran 600 head of cattle and he was considered a small operator. Mr. Durfee said that at that time the same vegetative types were in existence, but with much better density than at the present time. The Sandy Ranch development was started in 1904. Mrs. Durfee remembered that in 1911 the Sandy Ranch was raising alfalfa. Mr. Durfee stated that the deep wash cut in the bedrock on the north side of the Sandy Ranch on Oak Creek was there when he first went into the country....The wash on Bitter Creek Divide has cut in the last forty-five years [since the early 1900s]....He attributes the accelerated erosion that is present in much of the Henry Mountain area to overuse by grazing livestock. [95]

George Durfey's son, Golden, spent much of his early life herding sheep in the Henry Mountain and Waterpocket Fold country. In a 1992 interview, Golden Durfey recalled that before the Taylor Grazing Act there were numerous herds, all in competition for the same ranges. [96]

Contributing to the impacts on the range were the enormous sheep-shearing pens at the Durfeys' Notom Ranch and at Sandy Ranch just a few miles to the south. Golden Durfey remembered that his family's sheep shearing operation lasted for about 45 days each spring, when as many as 30,000 sheep would be shorn. [97] The BLM survey reports:

From the year 1900 up to 1934 when the Taylor Grazing Act was passed, some 50,000 sheep were sheared annually at pens in Notom on the north and at Sandy Ranch. During the shearing period these sheep were allowed to graze unrestricted on the surrounding public domain. This condition, with unrestricted grazing from the ranches, depleted the range forage in the upper valley to a point where Russian thistle predominates, and sheet, gully and wind erosion is prevalent. [98]

While heavy, competitive sheep grazing predominated on the eastern side of the Waterpocket Fold, sheep and cattle were also roaming unrestricted in what is now the northern district of Capitol Reef National Park. On the Hartnet Mesa section, between the South and Middle Deserts, another BLM survey described past use:

Prior to passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, large numbers of livestock were brought from Wayne, Sevier, and Emery Counties to winter on these lands. Many of the animals remained on the range year-long, resulting in progressive destruction of soils and vegetation. Reports from stockman [sic] in the area indicate that many trespass horses used the area until about 1955. Prior to 1946 there were at least 163 cattle and 20 horses licensed yearlong in this area. [99]

Guy Pace, a prominent rancher whose livestock graze on the Hartnet, believes that the majority of these large herds belonged to out-of-state operators. [100]

This pattern of unregulated, competitive range coupled with economic depression and drought is the same pattern found elsewhere in Utah and throughout the West led to the perceived need for federal regulation. That regulation turned out to be first the U.S. Forest Service permit system and, ultimately, the 1934 Taylor Grazing Act.

The Taylor Grazing Act's Impact On The Waterpocket Fold

Country

While the onset of grazing regulations in the national forests exposed many ranchers to the allotment and permit system as early as 1905, passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934 made it impossible to avoid federal supervision. The first director of grazing, Farrington Carpenter, had determined that the only successful means of enacting grazing regulations was through the hands-on cooperation of local ranchers, just as the U.S. Forest Service had concluded at the turn of the century.

At a meeting on October 22, 1934, Carpenter and his staff met with a delegation of 300 Utah cattle and sheep operators in Salt Lake City to familiarize the area ranchers with the Taylor Act's details and to gather information unique to Utah's ranges. In December, another meeting was held. This one was attended by approximately 200 livestock representatives, who met in Salt Lake to draw the boundaries for eight grazing districts in Utah. [101]

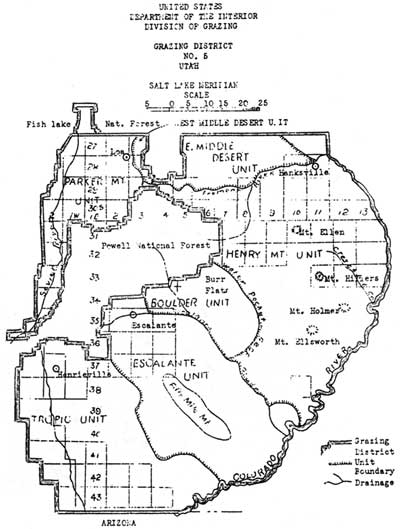

The area that includes Capitol Reef National Park was placed in Grazing District 5, officially established on May 7, 1935 (Fig. 34). [102] Each district had an advisory board, elected by its permittees, responsible for setting the original carrying capacities and the first line in settling disputes. The districts were then divided into allotments with one or several common users. Community and individual allotment committees were charged with setting up their own preliminary capacities and periods of use. [103] While it appears permits were issued almost immediately, they must not have carried much weight since permit priority was not clarified until January 1936 and the district offices were not established until a year after that. [104]

|

| Figure 34. Utah Grazing District #5. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

At the January 1936 meeting in Salt Lake City, representatives from all the district advisory boards throughout the West gathered with the fledgling grazing service to decide on long-term regulations, the most important being the establishment of range fees and standards for grazing permits. Fees were initially set at five cents an Animal Unit Month (an adult and unweaned infant per month) for cattle and horses, and one cent an animal unit for sheep and goats (5 sheep = 1 AUM). [105]

Grazing permits, patterned after the forest service requirements, were to be issued according to a specific order of preference. First choice went to those with prior use (those with range claims for the previous five years) who had sufficient private or commensurate lands adjoining or close to the range in question. This decision was in line with the Taylor Grazing Act's original wording, and was also consistent with the traditional tenets of private property and prior use. Secondary permit priorities were for those with commensurate property but no prior use, followed by those with prior use but little or no property, and finally, everyone else. [106]

The link between property, prior use, grazing fees, and district advisory boards ensured that local, established users would carry the most weight in determining how the public domain would be used. The stabilization of the livestock industry, one of the primary motivations for the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act, was virtually guaranteed by this kind of system. It would be up to the U.S. Grazing Service and, after 1946, the Bureau of Land Management, to develop the other motivation: rehabilitation of the range.

At first, and some would say ever since, the federal officials charged with monitoring these new regulations were too few, and were too poorly funded to implement successful range conservation. Due to the lack of appropriations and manpower, the district graziers concentrated on means by which they could constructively cooperate with the local ranchers to gain their trust for the future.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (ERA) range improvement program was significant in showing ranchers that federal action could be positive. In its first year, the grazing service was given 60 Civilian Conservation Corps camps with approximately 12,000 workers to develop range improvements throughout the West. At that same October 1934 meeting with the ranchers and Director Carpenter, the Utah office of the ERA discussed potential improvement projects with the livestock operators. They determined that "work consisting of development of springs and seeps, construction of small reservoirs, drilling of wells, and the installation of tanks and troughs, would best serve the most pressing needs." [107]

Roads and stock driveways were also built with this unique federal assistance. With $200,000 of ERA money allocated to Utah one week later, advisory boards of ranchers met with the ERA engineers to determine what projects would benefit the most people. [108] In Garfield and Wayne Counties alone, 37 springs were improved for livestock use, four wells dug, four stock reservoirs built, and five trails either constructed or improved. While it is hard to determine if any of these range improvements is within Capitol Reef National Park, the names of these projects (which often reference local landmarks) suggest that at least a half dozen of these federal relief range improvement projects were completed within what is now the park boundary. [109]

Another early focus of federal management of the Waterpocket Fold country was eliminating some of the competition between sheep and cattle on the desert winter ranges. In 1935, competing Wayne County sheep owners and Garfield County cattle ranchers went to a U.S. Grazing Service hearings officer in Richfield to plead their cases. The sheep owners said they needed at least one month of winter grazing in the Circle Cliffs as part of their annual herding cycle. The cattle owners, who lived in the Boulder area close to the Circle Cliffs range, complained that the sheep grazing had destroyed their traditional, and now federally approved, range. During the course of testimony, Boulder rancher John King emphasized the adverse vegetation change resulting from this competition between cattle and sheep:

[All that's left is] a little shadscale, sagebrush, about all killed. No grass at all to amount to anything, only way on the ridge farthest away from water. But along the head of Horse Canyon or in the Flats there is some sagebrush there but it is pretty well killed. All the [Brigham] Tea is killed out there. Not much grass or browse. Spots of shadscale and sagebrush. [110]

The hearings officer concluded in favor the Boulder cattlemen, principally because they had prior use and could demonstrate closer commensurate property. Specific cattle and sheep allotment lines were drawn that effectively eliminated the Wayne County sheep herds from legally venturing onto the Circle Cliffs. Anne Snow observed that this curtailment of the range, coupled with cuts in the national forest sheep permits, drove some sheep owners out of business and caused others to switch over to cattle. [111]

Increased regulation, a lack of herders, and predators were the main reasons why sheep numbers steadily declined after the Taylor Grazing Act. The impacts of uncontrolled, year-long competition between sheep and cows throughout the late 19th century and into the 1930s is still evident on much of the grazed land along the Waterpocket Fold, including much of Capitol Reef National Park. Later attempts to rehabilitate the land by the Bureau of Land Management will be examined below.

Early Relationship Between Ranchers And Federal Land

Managers

As mentioned earlier, the beginning of the forest permit system had exposed some tensions between traditional users and new federal attempts to regulate resources. The Great Depression and war years of the 1930s and 1940s created further hardships, as well as determined resistance, from some ranchers opposing further U.S. Forest Service controls.

Livestock were being killed to keep them off the market in the early New Deal Days. Stockmen continued to hold their numbers up, hoping for better times. They fought reductions in number with all of their organizational ability. A group of stockmen at Escalante and another at St. George were especially strong in their opposition to further reduction in number....Forest officers knew what was happening but found opposition to change solidly entrenched against them. Meetings were continually held with stock associations, some lasting until 2 to 3 A. M. before either side would concede a point....There was extreme feeling between stockmen and Forest Service during this period and many reductions were forced through regardless of feelings. In most cases these reductions were even yet too small to solve the overgrazing problems and the ranges continued to decline....Many petitions were drawn up by the associations to get forest officers removed during the 1930s and 1940s. The Escalante livestock association petitioned against nearly every ranger they had over a period of 20 years. These efforts by stockmen though sometimes successful did not change the policy of the forest service to get the facts and proceed to instigate reductions on the basis of factual information. [112]

This kind of resistance to federal grazing policy was by no means universal. Many of the ranchers felt that both the forest service and grazing service regulations were needed, so long as their traditional rights and usage were respected. Golden Durfey, for instance, was mostly positive when asked his opinion of the Taylor Grazing Act and later BLM policies:

Well, we've got it and we've got to live with it and we do. And we have some people, some heads of it that are good and some that are bad. But it's better than it used to be. And then we're better too. We've learned to live with it. You know. They've learned to live with us and we've learned to live with them. [113]

Rancher Guy Pace concurred:

The Taylor Grazing Act was, I think, very necessary. What it did, it put people, it controlled where they were. Particularly sheep operators. See, those sheep used to go on the Henry Mountains and they just run wild. The people that owned the sheep was trying to feed the whole country in front of someone else. And the Taylor Grazing Act set up allotments [mostly for] cattle. And what they tried to do, is if you ran so many cattle in a certain area, that's where you stayed. [114]

Thus, by the middle to late 1930s, federal grazing regulations were in place on the remaining public domain. While there was certain resistance to federal regulation, especially when it meant herd reductions, the overall opinion was that the Taylor Grazing Act and U.S. Grazing Service policies stabilized the Western livestock industry. Whether it stopped damage to the fragile Western landscape is still being debated.

Ranchers and the federal grazing control agencies, each with different experiences and time-honored beliefs, attempted to find a middle ground in order to avoid conflict. Lack of money and understanding, rancher resistance, and the threat of congressional investigation prevented the federal agencies from instituting range controls as soon as they would have liked. On the other hand, cultural, religious, and traditional ranching values were difficult for the southern Utah livestock operator to put aside.

During the 1930s, the unquestioned belief, the paradigm, was that public domain throughout the American West was to be used for grazing, mining, or timber. Public lands, therefore, were placed under the control of these interests, provided they followed the specified controlling federal land managers' policies. The practice of setting these lands aside for recreation was still decades away.

In the meantime, there was a growing feeling among local tourism boosters that at least some of the canyon country of southern Utah should be brought into the national park system. The prospect of another, even stricter, federal agency entering the land control arena was more than some ranchers were willing to accept. If the relationship between the USFS or BLM and the ranchers was tense, imagine the reactions toward a new federal agency whose mission included the elimination of grazing from traditional grazing lands.

Grazing During The Early Years Of Capitol Reef

National Monument

General National Park Service Policy: 1916 To 1934

While it is often assumed that grazing is not allowed in national parks and monuments, this is not the case. According to the 1916 National Park Service Origins Act,

the Secretary of the Interior may, under such rules and regulations and on such terms as he may prescribe, grant the privilege to graze live stock within any national park, monument, or reservation herein referred to when in his judgment such use is not detrimental to the primary purpose for which such park, monument, or reservation was created. [115]

Because of this clause in the enabling legislation of the National Park Service, and because of traditional grazing in areas later added to the national park system, many of the older Western parks and monuments continued to allow grazing. Some parks gradually phased out grazing, while others actually increased livestock usage, particularly during the livestock range expansion of World War I. [116] For example, to the question of whether grazing would be allowed in an expanded Sequoia National Park in 1918, Acting National Park Service Director Alexander Volgelsang responded:

We are unable to see how the transfer of any of the lands covered by these measures from the forest service to the National Park Service will in any way affect the grazing problem, as there never has been any thought of prohibiting the utilization of the grazing areas in this region during the existing emergency or even after the war is over. [117]

By the 1930s, however, the growth of the national park system into previously grazed areas created increasing conflicts with ranchers. In southern Utah, this was clearly evident with the ranchers' resistance to the National Park Service proposal to include a large part of the Colorado Plateau in an Escalante National Monument. As a direct result of these negative reactions by livestock interests, when Capitol Reef National Monument was created on August 2, 1937, the boundaries were consciously created to eliminate as many grazing permits and as much grazing potential as possible. [118]

Establishing A Grazing Policy At Capitol Reef National Monument

After Capitol Reef National Monument was established, National Park Service officials would find themselves forced to deal with periodic grazing concerns, even though it was believed that "gradual, even immediate, elimination of this range stock should not present a critical problem." [119] While the number of livestock and acreage of area grazed were relatively small, the economic dependence and traditional lifestyles of the isolated local communities, as well as previous and perpetual impacts on the natural ecosystems, dictated that grazing would forever be a concern for managers of Capitol Reef.

From the outset, even the presidential proclamation that established this small, 37,000-acre monument in the northern, spectacular section of the Waterpocket Fold specifically addressed the movement of cattle across monument lands. It states, "Nothing herein shall prevent the movement of livestock across the lands included in this monument under such regulations as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior and upon the driveways to be specially designated by said Secretary." [120]

This wording was inserted into the proclamation "to meet the needs of local stock growers in the movement of livestock." According to Acting Secretary of Interior Charles West, this phrasing was needed to protect ranching interests, as he had already signed departmental orders excluding the land within the monument boundaries from Grazing District 5 and revoking the grazing service's stock driveway withdrawal, which covered 3,480 acres now within the national monument. [121]

The lack of an on-site custodian at Capitol Reef until 1944, however, and the National Park Service's emphasis on development of roads and the Fruita headquarters area would significantly control grazing within the new monument. The rugged canyon labyrinths, physical isolation, private lands, lack of fencing, and a slowly evolving grazing service staff certainly did not help. In the face of these limitations, National Park Service officials tended to respond to grazing conflicts with policies that were neither enforceable nor even made known to the livestock owners.

From the beginning, grazing was never adequately addressed. Only a week after the presidential proclamation, Zion National Park Superintendent Preston Patraw, who was given jurisdiction over Capitol Reef, wrote Regional Director Frank Kittredge concerning "the more important projects" at the new monument. Patraw saw establishment of stock driveways and control of trespass grazing as priorities. Of the seven projects listed, stock driveways were number one. Patraw wrote, "All the various drainage canyons cutting through the Waterpocket Fold are used as driveways. Under agreement executed with stockmen, this may be limited to one driveway when properly developed. Development of a stock driveway will protect the other canyons." [122]

Patraw also believed that "grazing may be eliminated immediately over much of the monument if exclusion fences on the boundary and drift fences can be constructed now....For adequate protection of monument lands from grazing and other unauthorized operations...a permanent ranger resident in the monument is needed, and of course a ranger station is required." [123]

Thus, it appeared that grazing issues would be addressed from the beginning. In Regional Director Kittredge's response, however, grazing was completely ignored in favor of issues that had a greater consensus: long range planning and development of roads and other public accommodations. [124] The regional director put grazing policy on the back burner. In fact, all of Capitol Reef National Monument was given low priority: it did not even receive a volunteer custodian until 1944, and was not officially "activated" and given a separate, yearly budget until 1950. [125]

Two years later came what appears to be the first attempt to get specific information on grazing within the monument. Zion National Park Assistant Superintendent John M. Davis contacted Rulen Meeks, a prominent local rancher from Bicknell and member of the local grazing advisory board. According to Davis, Meeks told him that there were seven permittees with approximately 215 head of cattle, 300 sheep, and 20 horses, which grazed lands "not confined entirely in the Monument but include land outside as well." [126]

Although the information, as detailed by Davis, is not specific to allotment, it appears that Will, Dez, and Joe Hickman's 85 cattle had the southern half of the Meeks Mesa Allotment. James Pace's 300 sheep and Walter Smith's 35 cattle were assigned either to the Meeks Mesa or Torrey Town Allotment, and Clarence Mulford's 60 cattle and 20 horses were in the Fruita Allotment, which included his own private lands. In addition, George Clark held a permit to graze 35 cattle throughout the winter in Capitol Gorge, within monument boundaries. [127]

Davis also mentioned the traditional stock driveways used in the monument:

Grand Wash is used as a stock driveway only by the Meeks brothers. Capitol Wash and Pleasant Creek are generally used by all livestock owners. Pleasant Creek is used the most because of the pressure of poisonous weeds in Capitol Wash.... Stock using driveways through the Monument are supposed to make at least five miles a day. [128]

As part of the same study, Davis wrote a memorandum to his superintendent on May 1, 1939, detailing the lack of information pertaining to grazing within the monument:

The Capitol Reef [file] has been searched and nothing can be found on the minutes of any meeting where grazing was discussed or decided upon. These files were also searched for instructions from our Washington Office on the handling of grazing in the Monument. In all correspondence there is very little said about grazing and apparently this problem was not given much consideration or considered an important factor in the establishment of the monument. [129]

Even though Davis did not find anything in the Zion files, a thorough examination of the investigations and correspondence relating to a potential Capitol Reef National Monument makes it clear that opposition from grazing interests actually played a significant role in the eventual size and status of the area. [130] This opposition, or the threat of it, may have been one reason why so little had been done about the issue since it had first been raised by Patraw two years earlier. Even with this admitted lack of information about grazing within Capitol Reef, Assistant Superintendent Davis was willing to predict that all grazing could be phased out "with very little opposition" and that the number of stock driveways could be reduced to one "without much inconvenience to stock owners." [131]

Davis's conclusions were reached without taking into account the need for expensive fencing to enforce a grazing phaseout, the large amount of private land on which stock was free to roam, and the extra time and adverse impact on resources or ranchers. This failure to recognize existing conditions and local attitudes when determining grazing policy would plague Capitol Reef managers for many years to come.

The Scientists Arrive

A chance to gain more information came with the visits of the first scientific surveys of the new monument in the fall of 1939 and the spring of 1940. National Park Service Field Naturalist Joseph Dixon was the first to visit the area in October 1939. His "Special Report on Geology, Flora and Fauna" deals little with the natural resources, concentrating more on the Civilian Conservation Corps-constructed trail up to Hickman Natural Bridge just outside Fruita. His listing of flora and fauna are cursory at best, and he never mentions any part of the monument outside of Fruita and the Fremont River canyon. Nor does he mention any plant life other than trees. In his recommendations, Dixon urges further study of the cultural and natural resources, but never mentions grazing or its impacts. In short, his report is of little value in assessing the state of natural resources at Capitol Reef. [132]

The following May, Regional Biologist W. B. McDougall spent two days in the monument assessing its vegetative cover. Unfortunately, only the first day was spent in observation, and even then only along the road corridor. The next day it started raining, so he thought it best to leave while the road was still passable. During this all too brief visit, McDougall attempted to itemize the typical vegetation and the impacts of grazing. [133]

According to the biologist, the vegetation consisted of widely spaced pinyon and juniper trees with scattered serviceberry, cliff rose, Mormon tea, squaw bush, silver buffaloberry, "and in some places, where it has not been eaten by cattle or sheep,....some grass." McDougall further observed:

Cattle overrun the Monument everywhere to the number of about 200 head or more. So far as I know, no permits are issued but it wouldn't make any difference anyway under present conditions because there is no resident custodian to look after the area. If all domestic animals could be removed from the area, it probably would support a herd of 200 or more deer....[T]his area represents a certain biological type and it is hoped that the time will come when it can be administered in such a way as to represent this type normally. Primarily, of course, it is a geological monument but it is large enough to be biologically significant if it could be properly protected. [134]

McDougall's account of the overgrazing at first seems like overwhelming evidence of the damage livestock was having on the entire monument. Unfortunately, McDougall hiked only near the road, which was one of the traditional stock driveways through the area and, thus, the most severely impacted area of the monument. May is also the month when the cows and their calves are waiting to be moved to the mountains for the summer. Therefore, McDougall's findings are neither complete nor valid.

Capitol Reefs Grazing Policy Takes Shape

As part of an overall review of grazing in the National Park Service in 1941, Zion Superintendent Paul Franke was asked to contribute information on Capitol Reef National Monument, since there was no mention of it in the Washington files. [135] Franke's response generated the first known grazing policy for Capitol Reef National Monument.

Franke first determined from District Grazier D. S. Moffitt in Richfield, Utah that (except for stock driveway use) no permits had been issued for any lands within the monument for the past year. However, he reported, "No doubt there is some unauthorized grazing by local stockmen and residents of the village of Fruita. Such grazing can not be brought under control until the monument boundary is fenced and protection personnel provided to enforce regulations in this area." [136]

Concerning the stock driveways, Franke's search of the files showed that no one canyon had yet been specified for such use. However, he wrote, "As soon as time permits a study of this use will be made and recommendations submitted for consideration in the designation of driveways by the Secretary of the Interior." Apparently, this study was never completed, as driveways were never specifically designated by the secretary. This meant that the traditional trails would be used as before. [137]

In the accompanying charts and grazing policy statements, the specific grazing impacts on monument lands were detailed. It was estimated that the stock driveways saw up to 1,000 head of cattle for about four days a year. Within the monument there were also 115 cattle and 30 horses that grazed 918 acres of private land, and 200 cattle on 2,474 acres of state or county land from two to three months a year. The amount of land "overgrazed by trespass stock due to lack offence and other controls" was estimated at 300 cattle over 6,760 acres of land for the three winter months. The remaining 24,542 acres, or 67 percent of monument lands, were considered too barren or inaccessible to grazing. The carrying capacity was determined to be 255 cows per month for the entire monument, or 40 acres per cow. [138]

The grazing policy statement, presumably written in 1941, ruled out the grazing of additional livestock on monument lands. This was justified by the already overgrazed condition of some park areas, and the lack of personnel to monitor livestock. The statement declared, "The Monument being already in a badly overgrazed condition, the placing of more livestock in the area cannot fail to seriously aggravate the existing undesirable conditions and would promote erosion of a damaging nature." [139]

The policy statement also established that "stock grazed in Capitol Reef are legally on trespass as no permits have been issued to graze." [140]

While this policy statement makes it clear that grazing was not permitted within monument boundaries except through the limited use of stock driveways, the lack of enforcement meant that some ranchers would continue to use their traditional winter grazing areas.

Grazing Issues And Conflicts At Capitol Reef:

1948-1957

In August 1948, 11 years after the monument's creation, Capitol Reef Custodian Charles Kelly discovered a well-used, recent cattle trail to the rocky mesas between Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge. Kelly inquired among the local ranchers as to whose cows were in the monument, and learned that George Clark of Torrey held a grazing permit for the area. [141] This is, presumably, the same George Clark who had a winter permit for 35 cows for the Capitol Gorge area in 1939.

Zion Superintendent Charles Smith wrote a letter directly to Clark informing him that grazing was not legal in the national monument and requesting that he get his permit revised by the Bureau of Land Management. [142] Since there is no record of correspondence between Smith or Kelly and the BLM on this matter, it is hard to determine why Clark was able to continue grazing within the monument for so long. Presumably, either Clark continued using his traditional winter range within the national monument without knowledge of or care about its no-grazing policy, or he had a 10-year permit for the area that was only then coming due.

While George Clark soon removed his cattle without complaint, this action stimulated the concerns of other local ranchers as to how they would be compensated for their grazing privileges in the Meeks Mesa, Torrey Town, or Fruita Allotments lands within the monument. Charles Kelly wrote:

They think that if they are excluded from the monument, the grazing service should give them some other grazing area; or if that can't be done, the park service should compensate them for the loss of their rights. To date they have made annual payments for these rights. The fact is they did not know just where the boundaries were, and believed they were on public domain....Actually, the cattle who wander into the monument do no particular damage, since there is almost no vegetation in that section. However, if this place is ever fenced, the matter will have to be adjusted. The cattlemen have believed they were within their rights, and I did not know until this week that they had grazing rights within the monument boundaries. [143]

This notice from Kelly elicited a detailed response from Superintendent Smith. Smith reiterated the old assumption that the range within Capitol Reef National Monument was of such little value that it had previously been considered unimportant. [144]

Smith went on to clarify National Park Service policy toward the use of stock driveways, the ranchers' permits, and the manner in which future trespass should be handled. According to Smith, several visits of national park officials in the late 1930s and consultations with the local grazing board had determined that the monument would allow livestock drives over the Fremont, Grand Wash, Capitol Wash, and Pleasant Creek gorges. The drives were to be expeditious and were not to take more than one day through the monument. [145]

As to the ranchers' belief that their permits covered lands within the monument, Smith recited the 1941 statement by the district grazier that no permits had been issued for the monument; thus, "[t]his makes it very definite that there are no grazing rights on government lands within the area." [146] One fact Superintendent Smith failed to mention was that just prior to the presidential proclamation back in August 1937, the secretary had ordered all monument lands excluded from the grazing district. Thus, even if the U.S. Grazing Service, and later BLM, had issued permits, they should have been no longer valid. Smith also advised Kelly to tell the individual livestock owners that it was their responsibility to get permits adjusted, although the National Park Service would assist with clarifications. There is also no mention of compensation in those cases where the number of permitted livestock was reduced.

Smith realized, though, that with a total lack of fencing and boundary markers, a certain amount of trespass grazing was not only inevitable, but tolerable. He wrote:

We have no doubt that trespass grazing is quite common, unintentional or otherwise. We are not going to shut our eyes to flagrant trespass nor are we going to demand that the livestock men ride daily herd on their stock. We expect them to be reasonable and to show some respect for the regulations. If they do this, and do not take advantage of our attitude we will tolerate minor trespass....When physical improvements are made and other development take place the stock will be excluded entirely and the owner will have to see that they do keep out. Any tolerance we display now cannot be used as a basis for assuming that a privilege exists. [147]

In other words, while grazing was not permitted within the monument, there was little the National Park Service could do at that time to prevent all but the most flagrant cases of trespass. Thus, by the end of Capitol Reef's first decade, there was a semblance of a grazing policy, but it was vague and still unenforceable. As long as this was the case, the local ranchers would continue to graze their traditional ranges.

Toward the end of 1950, soil and conservation officials arrived to assess the potential for a comprehensive plan for Capitol Reef. As part of the initial soil survey, the impacts of grazing were noticed, as was the fact that severe drought had caused winter grazing in the immediate area to be curtailed for the last several years. It was anticipated, however, that livestock would soon be returned to area. Soil conservationists warned that if stock were allowed to continue trespass and unmonitored use during stock drives, there would be little point in beginning an extensive erosion control program. [148] The soil conservationist also mentioned that the grass types found in the monument included the dominant galleta, with lesser amounts of alkali sacaton, blue gamma, sand dropseed, and salt grass. It is not known exactly where these grasses were found or how extensive was the survey. [149]

By the mid-1950s, it seems that grazing conflicts at Capitol Reef National Monument had worked themselves out. So long as the ranchers were willing to control stock trespass as best they could, nothing was said by the Capitol Reef's new superintendent, Charles Kelly. In the 1953 Capitol Reef National Monument Master Plan, Kelly mentioned continued trespass problems, but expressed more frustration with the manner in which cattle were driven through the monument. He complained, "The monument is unfenced, and stray stock drift into it occasionally. However, the vegetation is so sparse that little damage results. Unfortunately, there is no designated stock driveway, and herds of cattle pass through without supervision, usually bedding two nights on the monument." [150]

One year later, however, Charles Kelly lost his patience with wandering stock. The incident apparently began when one of the private landowners inside the monument, Cass Mulford, refused to keep his cows and horses from crossing onto the monument. Kelly was particularly irate because the cows were grazing in the campground, at that time located on Sulphur Creek north of the present visitor center. According to Kelly, two other ranchers decided that if Mulford could get away with trespass, they might as well let their cows onto the monument lands, too. Kelly notified the regional office in Santa Fe of the problem and recommended that his superiors send him a "rather strong order" to remove the cows. But the superintendent also warned this may not work, and desired to know what other course of action he should take. Kelly also consulted the Richfield office of the Bureau of Land Management to see how they handled livestock trespass cases. [151]

This memorandum sparked a flurry of correspondence between Kelly and the regional office over how to handle grazing trespass. The regional office requested more information, researched applicable fence and impoundment laws, and asked Kelly to write down as many specific details as possible. Kelly was told that, if necessary, the sheriff should be called in to impound the offending animals. Assistant Regional Director Hugh Miller also warned Kelly to proceed cautiously, since this would be "bad public relations if it is necessary to go the whole way." He asked, "Is the total damage, plus nuisance, worth it?" [152]

Kelly responded that the sheriff, being one of the local Mormons, would probably not cooperate, and "[t]he county attorney would do so only reluctantly." Superintendent Kelly's solution was to build a drift fence across Sulphur Creek just west of the ranger station to prevent more strays entering the campground. He also suggested that the regional office issue Kelly an order to keep the monument free of cattle.

"I can then show this order to the offenders," Kelly wrote, "and it will have more weight than if I issued it here. They will not be so apt to hold it against me personally when the rule is enforced." [153]

As for public opinion, he complained:

I realize that the natives here will not be happy, but they have ceased to cooperate and after ten years it is time to let them know that this is actually a national monument. We also have to consider relations with the traveling public. Last summer a locoed cow walked through the tent of a camper in the night, and the resulting publicity was certainly not complimentary to the park service. When campers are kept awake all night by prowling stock, and their camps are messed with fresh manure, they ask me whether Capitol Reef is a national monument or merely a cow pasture. [154]

Eventually, the requested order from Regional Director Minor R. Tillotson arrived. Kelly then notified all local livestock owners that he had been directed to do whatever it took to keep stock off the monument. If trespass continued, Kelly warned, he would "be forced to resort to legal procedures to correct the situation." [155]

Kelly also informed the ranchers that no trailing or bedding of livestock would be permitted in the campground area, and that Utah Highway 24 would continue to serve as the designated stock driveway. There is no documentation available that elaborates on exactly when this decision had been made, or by whom. This is especially puzzling since only a year before, in the 1953 master plan, Kelly stated that there was no one designated stock driveway through the monument. [156]

This order seems to have satisfied both the ranchers in question and Superintendent Kelly for the time, as there is no more reference to the matter. After this episode, grazing once again resumed its place on the back burner, only to flare up again in 1957.

Kelly's nearest neighbors, Merin and Cora Smith, had a few cows that would apparently wander onto National Monument property from time to time. In June 1957, Kelly discovered that these cows had eaten much of his flower garden and "ruined" his vegetable garden and younger fruit trees. According to Kelly, he confronted Merin Smith and told him that he "would not any longer stand his pasturing his cattle in [Kelly's] yard." Smith, recorded Kelly, responded irately that his cows were there long before Kelly and that "he ha[d] always pastured his cattle on the government property (true) and still intend[ed] to do so" [parenthetical notes are Kelly's]. The Smiths then told the superintendent to remove the National Park Service picnic tables from around the Fruita schoolhouse, which was on their property. [157]

Charles Kelly may not have been the best man to handle an issue as sensitive as livestock trespass on National Park Service lands. Nevertheless, these examples do point out that if grazing policy is not clear, well known, and enforceable, then there is significant potential for conflict.

Nevertheless, the tiny monument's grazing problems paled in comparison to those of other national parks and monuments. Excluding eastern parks where livestock pasturage occurred and the more multiple-use-oriented national recreation areas, the 1957 totals for grazing within the national park system included 112 permittees. These permittees had approximately 10,000 head of cattle, 860 horses, and 15,000 sheep and goats. These accounted for 88,591 AUMs permitted on National Park Service lands. The largest AUMs were concentrated in Utah's Dinosaur National Monument, with 17,000 (mostly sheep); Grand Teton National Park, with 11,600 (cattle); Grand Canyon National Monument, with 15,000 (Navajo sheep); and Organ Pipe National Monument, with 13,000 (cattle). [158]

At Capitol Reef National Monument, grazing concerns lessened as Mission 66 development money was used to fence portions of the monument boundary, and special use permits were issued to regulate the monument's stock driveways. [159]

While Capitol Reef's grazing problems appear relatively minor throughout the first three decades of monument's history, this would suddenly change when another presidential proclamation in 1969 increased its size by 600 percent. This new monument land consisted of public domain within and surrounding the rest of the magnificent Waterpocket Fold, principally used for winter grazing range. Before discussing the implications this expansion, it is important to touch briefly on USFS and BLM range management of the public domain that would soon be added to the national park system.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/adhi/adhi12b.htm

Last Updated: 12-Nov-2020