|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

INTRODUCTION

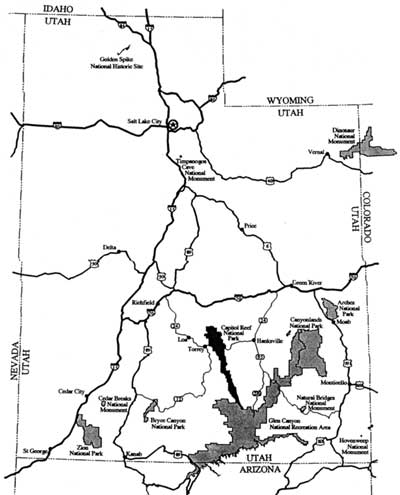

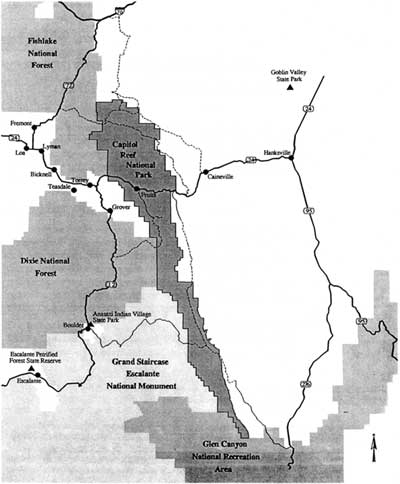

Located in south central Utah, Capitol Reef National Park is the state's fifth and most recent national park (Figs. 1 - 2). The other "crown jewels" in Utah surround Capitol Reef: Canyonlands and Arches National Parks are to the northeast, Bryce Canyon and Zion National Parks to the southwest, and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area is immediately to the east and south. The long, narrow Capitol Reef National Park envelops the Waterpocket Fold, a classic monoclinal uplift of ancient sedimentary rocks rising for almost 80 miles from the slopes of Thousand Lake Mountain in the north to the low desert canyons of the Colorado River. The immense, almost solid cliff line of the Waterpocket Fold (, named by earlier geologists for its sculpted water holes), warns those traveling east from the grassy, timbered highlands of central Utah of the forbidding maze known as the Colorado Plateau.

|

| Figure 1. Location of Capitol Reef National Park in Utah. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 2. Current boundary of Capitol Reef National Park. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Capitol Reef's north-to-south-running cliffs and twisting, narrow canyons have always seemed a barrier to travel. Local tradition holds that the name "reef" came from early prospectors who once sailed the oceans, wary of similar outcroppings. The "capitol" comes from the white sandstone "domes" atop the higher sections of the reef. Records show only a few explorers, ranchers, settlers, and adventurers dared to pass through the Waterpocket Fold country even after the national monument was proclaimed in 1937.

Fifty-five years after the monument's establishment, most visitors, local residents, and government officials are unfamiliar with the diverse resources within Capitol Reef's boundaries. The extremely rugged landscape limits access to foot traffic or the long- distance views from dirt roads. Because the main transportation routes through this part of Utah run east and west, slender north-to-south-oriented Capitol Reef National Park is quickly seen, admired, and then passed through. The usual quick look at Capitol Reef reveals only a maze of multicolored rock slopes and cliffs and the contrasting orchard oasis of Fruita along the Fremont River. The park's true complexity is realized by only a few: even among those who have spent years in the Waterpocket Fold, there are still canyons yet to be explored or native flora and fauna yet to be seen.

Fewer still have come to understand its human history. The few perennial streams through the Waterpocket Fold served as routes and semi-permanent camps for American Indians from early Archaic times up through the historic-era hunting trips of Utes, Paiutes and Navajos. The Fremont culture of 700 years ago was first identified along, and named for, the river draining Capitol Reef. Artifacts, encampments, pictographs, and petroglyphs are abundant throughout the park. The Euro-Americans who first explored the region only skirted the borders of the Waterpocket Fold until well into the 1870s. The people who finally settled the area were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). Their philosophy toward the land was not unlike that found elsewhere on the frontier. To survive, they confronted the land, battling to tame it by every means possible.

Some actually succeeded. The ranchers found grass for cows and sheep, prospectors discovered small speckles of promising ores, and farmers found a few perennial streams along which to homestead. Yet the isolation and constant hostilities of nature allowed very few outside the established communities to remain for any length of time.

By the 1930s there was a growing feeling in southern Utah that this convoluted landscape deserved national park status. Park boosters, with at least the tacit support of National Park Service officials, promoted the benefits of new roads and other developments that would bring in badly needed tourist dollars. Promotion of Wayne Wonderland (as the area was then called) became complicated, however, since a majority of local residents were ranchers, miners, and other proponents of multiple-use lands. After years of dependency on federal forest service grass and timber and grazing service lands, these people were not so sure they wanted a strict resource protector like the National Park Service in their country. The ranchers, however, withdrew their formal opposition contingent on the national monument remaining relatively small and not infringing upon their traditional grazing privileges.

In 1937, national monument status was granted to a 37,000-acre tract, which included Fruita and the high domes, cliffs, and canyons of the Capitol Reef section of the Waterpocket Fold. Yet, World War II postponed any substantial investment in Capitol Reef until well into the 1950s. Poor roads and traditional travel patterns continued to keep Capitol Reef a barrier to most tourists throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Meanwhile, the local economy was sustained through ranching and a short-lived uranium boom.

When a paved road was finally put through Capitol Reef in 1962 and new facilities, such as a visitor center, were erected through the Mission 66 program, visitation began to rise. The average visitor stay was still less than a day, so the few fledgling motels and restaurants in the area saw only a small increase in income. The average American, let alone the still infant environmental movement, had never heard of the place.

By the late 1960s, local residents considered Capitol Reef National Monument a nice place to go for hikes, a family gathering, or possibly a maintenance or clerical job. The rangers and superintendent, typically outsiders, were simply tolerated. Then in the last hours of his administration, President Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation that enlarged Capitol Reef by 600 percent. The monument was no longer condoned by many of its neighbors: it was resented. The monument expansion came without warning and struck at the basic fears of those economically dependent on federal multiple-use lands. Despite the fact that the expansion took in relatively few grazing permits and mining claims, the action itself infuriated many.

In the next couple of years, a series of congressional hearings considered alternatives for the recently expanded monument. Some preferred a national park while others wanted the southern half as a multiple-use recreation area. Local land users and urban environmentalists squared off. The National Park Service, caught in the middle, attempted to please all it could while still maintaining agency integrity, as well as the resource integrity of a national monument now the size of Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks combined.

In December 1971, a compromise scaled the boundaries down a bit and, more significantly, made Capitol Reef a national park. Yet, multiple land-use issues such as mining, grazing, and road building, both within and surrounding park boundaries, were not adequately resolved with the park's creation. Local preferences often conflicted with the desires of national environmental organizations as well as agency policies, creating emotional barriers that have only recently been addressed.

Today, the local population maintains many of its traditional land-use ethics. Still largely Mormon, nearby communities are wrestling with the realities of diminished traditional resources, increasing federal government regulation, and an influx of tourists that bring not only money but also beliefs that are perceived by many as threats to their lifestyle.

The existence of a national park slicing through the heart of two rural Utah counties has not been easy on park managers or its neighbors. From local ranchers still attempting to use its ranges, to politicians still hoping for the miracle of economic development, Capitol Reef is now seen as much a political as a physical barrier. For other neighbors, visitors, and environmentalists, Capitol Reef represents a beneficial barrier: a jewel to be explored, enjoyed, and left preserved in its natural state. The National Park Service, which has only recently acknowledged that Capitol Reef is no longer a "small" park, continues to be torn by these divergent needs, delicately balancing the right to access with the need to preserve. Capitol Reef National Park, once a barrier, is now at a crossroads.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/adhi/adhi0f.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002