|

The Valley of Opportunity: A History of West-Central Colorado BLM Cultural Resource Series (Colorado: No. 12) |

|

Chapter II:

THE FUR TRADE AND GOVERNMENT EXPLORATION

"When I first came to the mountains, I came a poor man. You, by your indefatigable exertions, toils and privations, have procurred me an independent fortune."

—William Ashley

Fur trappers in search of beaver were the first Euro-Americans to visit west-central Colorado. These buckskin clad adventurers constituted the vanguard of American civilization as they spread out into the Rocky Mountains during the 30 years from 1810 to 1840. The mountain men, as hopeful capitalists, found and exploited the area's natural abundance for the first time. This use of resources differentiated these Anglo-Americans from previous travellers into the region who had gone to explore or trade with the natives. The fur business, based on the need for beaver pelts used in making hats, depended upon fashion trends to create a demand and stabilize prices. During the 1820s and 1830s, European male dress standards required beaver hats which caused a boom in trapping activities. These decades marked the high point of the mountain man and his fur trade. However, the first trappers were in Colorado well before 1820. [1]

The fur trade in central Colorado began in two places. The upper Arkansas River, near Leadville, Colorado, was visited in 1811, by the famous fur entrepreneur Manuel Lisa. Lisa, in that year sent a party, led by Jean B. Champlin and Ezekiel Williams, to trade with the Arapahoe. In the process of trapping they discovered and trapped the upper Arkansas River Valley, but due to the extreme height of the Rockies, they failed to pass into the Colorado River Basin. Natives wiped out this group and only Williams made it back to Santa Fe in 1813. [2]

The next recorded trapping party was the Joseph Philibert expedition of 1815. Organized by Auguste Chouteau and Julius DeMun of St. Louis, this party was typical of many of the early trapping efforts, being made up of men of French ancestry based in St. Louis, Missouri. That city became the center of the western fur trade during the early nineteenth century. They trapped along the upper Arkansas River to the head of the valley near Leadville, where they encountered Caleb Greenwood in charge of a Lisa outfit working the area. The Chouteau and DeMun group operated along the upper Arkansas for several years, but apparently failed to cross the Continental Divide into the Colorado River Basin. [3] Trapping on the crest of the Rockies came to a sudden halt in 1817, when Spanish troops captured American traders along the Front Range. The American trappers were jailed and only after considerable difficulty were they released. [4]

Mountain men may have trapped the Eagle Valley as early as 1813. Local legend maintains that fur baron John Jacob Astor's men established a post at Astor City, near Minturn, Colorado, while returning from Astoria in the Oregon Country after Astor had sold his holdings to the British North West Company. This myth was given some credence because of casual references to Astor City in the Rockies in Longfellow's Evangeline. However, there are no other records of this post and in all probability, the Astorians never trapped the Eagle Valley at this early date. [5]

Fur trapping came to a halt along the Arkansas River corridor by 1817, because of Spanish intervention, and a few trappers began to operate from Santa Fe by way of the San Juan Mountains. The Maurucio Arze and Lagos Gracia expedition of 1813, had skirted this area on the way to Utah.

In 1821, the citizens of New Spain (Mexico) overthrew Spanish rule and declared themselves an independent nation. With the revolution, New Mexico became "open territory" for trappers and traders. Americans, who had been excluded, now were allowed into the area. Taos, New Mexico, became a major trade center and by 1824, the San Juan Mountains and Colorado River tributaries became preferred areas for trappers because the region's heavier snowfall led to a more constant stream flow that in turn tended to produce greater quantities of high quality furs. The area saw the likes of Ewing Young, William Wolfskill, and others and for the first time, the interior of Colorado was being trapped. [6]

From the opening of the center to the end of the fur trade, there was little activity directly along the Colorado River. However, trappers used some of the river's tributaries extensively, as well as using the river and the valleys as routes into other trapping grounds. The upper Arkansas Basin was in continual use, including the Hugh Glen-Jacob Fowler expedition of 1824. These men were responsible for the opening of the route from St. Louis to Santa Fe. [7] During the 1820s, many trappers and traders passed through west-central Colorado. In 1822, James Ohio Pattie travelled much of western Colorado, followed two years later by five trapping parties led by William Wolfskill, Etienne Provost, Antoine Robidoux, William Huddart, and William Becknell respectively. These parties were headed for the Green River of Utah using the Dominguez-Escalante route from Santa Fe. During 1825, Thomas Long and "Peg-Leg" Smith, financed by Ceran St. Vrain trapped along the Grand (Colorado) River. James O. Pattie spent part of the 1826 trapping season on the Grand. The last fur expedition of the 1820s in west-central Colorado came in 1829, when George Yount, with an outfit of thirty men, trapped the Grand and Green Rivers. [8]

The fur trade in western Colorado boomed when William Ashley opened the Green River country in 1825, and began to exploit it. By the next year Ashley's group, which became the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, then owned by Bill Sublette, William Jackson, and Jedediah Smith employed the biggest names in the Colorado fur trade. [9]

The 1830s witnessed increased fur trapping and trading in western Colorado. During this decade mountain men worked the Crystal River, the Eagle River, the Gunnison River as well as the Grand. [10] The trappers included "Peg-Leg" Smith, Mark Head, and Jim Bridger. [11] The early years of the thirties were the era of the rendezvous, a system of central collection, employed by the fur companies. This meant that several times a year the trappers would gather at a pre-arranged place to exchange furs for goods and supplies, to drink and have a good time. These "fairs in the wilderness" generally turned into drunken brawls, but they did serve a purpose. Instead of having to go around and collect furs, the traders could simply meet with the trappers and barter. The rendezvous system came to an end in the mid-1830s with the advent of the trading post. [12]

Trading posts evolved in response to increasing threats from natives who objected to the incursions of the fur traders. The first forts in Colorado were established on the eastern plains to serve the buffalo trade. Bent's Fort, Henry Gantt's post, and others eliminated the need for the rendezvous. In the interior Fort Uintah, Utah, and Fort Davey Crockett, Colorado, served the northwestern part of Colorado. Central Colorado trade was concentrated at Fort Uncompahgre, also known as Fort Robidoux.

The post was built by veteran Taos trader Antoine Robidoux who, in 1837, left his carvings in the Book Cliffs near Fruita, Colorado. He also owned Fort Uintah. Fort Uncompahgre was built in 1828 near the junction of the Gunnison and Uncompaghre Rivers. This structure was a small wooden and mud fort built on a square. It afforded no real protection from hostile Utes. [13]

Fort Uncompahgre, the Western Slope's first general store, was a boon for trappers and traders in western Colorado. The fort's owner, Antoine Robidoux, a "bushwa" or trader, had long experience in the fur business, his father having started at St. Louis in 1790. Antoine was one of seven brothers, all of whom stayed in the fur enterprises. The post itself was licensed by the Mexican government and handled all matter of goods. It was the scene of many drunken brawls, inter-racial debaucheries, and the use of liquor to encourage the Utes to trade. As many as 20 trappers were based at Fort Uncompahgre, the most famous being Christopher "Kit" Carson, who, in 1840, trapped the Grand River. The post remained open until 1844, when the Utes burned it down, never to be rebuilt partly because of fashion changes that led to a depressed market after 1840. [14] Individual trappers, such as William Gant, on the Crystal River, or the Kimball brothers on Kimball Creek near Grand Valley, Colorado, continued to trap in western Colorado as late as 1882. The early 1840s marked the end of the fur trade as a big business all over the American West. [15]

The fur trade never impacted the Grand Valley because most travellers either avoided the region or simply passed through on their way to other, richer, fur lands. Perhaps it was the lack of access that prevented early development, or maybe the Rockies proved too stout a barrier. The only areas exploited were either north of the valley in the Flattop Mountains, the Eagle Valley and down the White River, or to the south in the Elk and San Juan Mountains.

The next major European thrust in Colorado was exploration in the 1840s. From 1800 to 1840, the Rocky Mountain West was the scene of competition between the British, Spanish, and Americans for control of the land. Spain originally claimed the entire area and maintained that control, despite threats of French incursion that ended with the Peace of Paris in 1763. The United States entered the contest with the purchase of Louisiana in 1803, that doubled the size of the country and made the crest of the Rocky Mountains the western boundary of the nation. The United States government recognized the need for exploration in the newly acquired territories west of the Mississippi River. When Louisiana was purchased no one knew what lay "out west". There was also a need to establish the boundaries of the region in that the Spanish claimed lands along the southern side of the territory while the British stated that the northern boundary was less than the United States thought. [16]

|

| The Grand River attracted fur trappers during the 1830s. This view of Ruby Canyon 1916, was little changed from the days of "Mountain Men". Photo by U.S. Geological Survey |

|

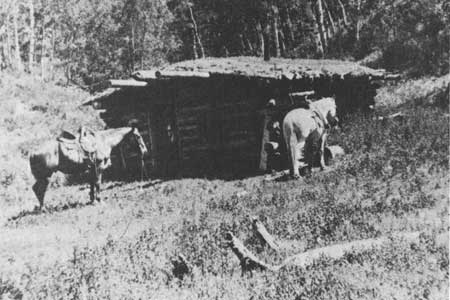

| Men who sought beaver and other furs lived in log cabins when they meant to stay awhile. Photo by U.S. Geological Survey+ |

The first expedition to map these lands came in 1803, when Lewis and Clark made their way to the Pacific Ocean via the Missouri River Basin. Then, in 1804, Zebulon M. Pike explored the front range of Colorado seeking the Red River which was considered the boundary between the United States and Spain. Pike reached no further inland than the San Luis Valley where he was captured by the Spanish. That put an end to exploration until 1819 when Stephen F. Long explored the northern front range of Colorado for the U.S. Army. This survey never penetrated into the center of the state because of the rugged Rockies. [17]

Western Colorado remained "unexplored" during the 1820s and 1830s, however, in 1830 and 1831, George Yount and other trappers laid out what was to become the Old Spanish Trail for future travellers and settlers. The North Branch of the trail followed the Gunnison River to its junction with the Colorado (Grand) and then west along the Colorado River into Utah. The Old Spanish Trail was never popular. [18] However, it did pique American interest in western Colorado.

The first time an expedition passed into west-central Colorado was in 1843, when John C. Fremont, the eminent Army explorer, crossed the area on his way to California. In that year, Fremont's expedition wound its way from Independence, Missouri, over the plains of Kansas and Colorado, up the Arkansas River valley to near present day Leadville, Colorado. Then it crossed the Continental Divide and marched into North Park from which the Fremont party moved across northwestern Colorado into Utah. They finally reached California in 1844. [19] On the return trip Fremont sought, but failed to find, the source of the Grand River. [20] This expedition proved only that the Rockies were a major obstacle that could not easily be crossed.

Fremont again went out in 1845. This time he travelled from Independence, Missouri to Bent's Old Fort where he hired Kit Carson as guide for the expedition. From the Fort the party passed along the Arkansas Valley, over the Continental Divide at Tennessee Pass, marched along the Eagle River to the Grand (Colorado) River, and then made their way north to the White River, north of the Flattop Mountains. Fremont followed the White River to the Green River and then west into Utah, and ended up in California via the Sierras once again. [21] Again, the benefits from the expedition were minimal; the Preuss map was the primary document produced and it was used by others for years. The expedition also proved that the Rockies were a brutal test of man's endurance and could not be used for massive migrations from Missouri to California and Oregon. [22]

In 1846 the Mexican War began. This put a stop to exploration in the western United States. The U. S. and Mexico were at war over the very lands being explored. The Mexicans went to war with the United States over the question of the annexation of Texas, the threat of the loss of California and the general question of American imperial expansion in the West. Americans felt that it was their destiny to have a nation from Atlantic to Pacific. This concept, called "Manifest Destiny", was a reason for the war. [23]

By 1848, the Mexican War had ended and the United States gained the southwestern quarter of the nation. The entire Louisiana Purchase was now combined with the present states of Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Idaho, parts of Washington and Oregon, and, of course, California. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo provided for the cession of these lands to the United States and the present border was established. In this way the United States completed the nation from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the West was ready to open. [24]

One of the most pressing issues in western politics was the development of a cheap, fast transportation system. To this end, Congress, mainly Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a Missouri promoter, began to press for a railroad. Once the nation had been consolidated, the reality of a rail line was possible. [25]

Naturally, when the matter of a transcontinental railroad came up, John C. Fremont was in the forefront. Having made a name for himself as an explorer in the early 1840s, and having the support of Benton, he was the prime candidate to lead transcontinental explorations. In 1848, Fremont led a party of explorers across the San Luis Valley and into the San Juan Mountains. In November the party became trapped in a snowstorm in the San Juan Mountains and several members of his expedition froze to death or died of starvation. Cannibalism occurred and when the party struggled into Taos, Fremont was disgraced for life as an explorer. [26]

Fremont's catastrophe in the San Juans put an end to exploration for a rail route in the central Rockies until 1853, when John Williams Gunnison of the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers was commissioned by Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, to find a route across the Colorado mountains along the Thirty-eighth parallel. His was one of five parties sent to look for pathways across the West. [27] Gunnison departed from Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 23, 1853, complete with survivors of the Fremont expedition as guides. Gunnison's party crossed the Kansas plains to the Arkansas River which they followed over the Sangre De Cristo Mountains. From here the group passed into the San Luis Valley, went over Cochetopa Pass, and then down to the Gunnison River Valley. [28]

Gunnison surveyed along the Black Canyon of the yet-to-be-named Gunnison River, over Cerro Summit, and on to where Montrose, Colorado, would arise. From that point, the party followed the Uncompaghre River to its junction with the Gunnison River and north along the Gunnison until it met the Grand, at the future site of Grand Junction, Colorado. There Gunnison's party headed west along the Grand River into Utah via Ruby Canyon. In October, 1853, along the Sevier River, Paiute Indians attacked the surveyors. Gunnison and all but four of the party perished in the raid. [29] To say the least, the loss of Gunnison's expedition dampened enthusiasm for a central Rockies railroad route, and the Gunnison report, completed by Lt. E. F. Beckwith, indicated that such a route would be difficult to build. The central Rockies were written off and a Wyoming route was considered the best alternative. [30]

The Thirty-Eighth Parallel route, while dismissed by many, was favored by the merchants and promoters of St. Louis, Missouri, among them Senator Benton. [31] In 1853, with Missouri backing, John C. Fremont undertook yet another, and as it turned out his last, expedition to west-central Colorado in search of a rail route. He traced the path of Gunnison, but leaving late in the season, again was trapped by snow on Cochetopa Pass. The group struggled off the pass and successfully reached the Gunnison River. From there they proceeded north to the Grand River and westward into Utah. [32] Also, E. F. Beale undertook an exploration of the same route in 1853, at the behest of St. Louis merchants. [33] These reports were less negative about the area's potential use by railroads than the Gunnison document.

The Pacific Railroad route race came to an end over politics. In the late 1850s, the specter of Civil War loomed over the nation. The question of both Kansas and Nebraska being accepted for statehood became a national issue and the partisan politics that followed caused sectionalism to destroy the railway surveys concept. The South demanded the line be constructed along a southern corridor while the North wanted a transcontinental route along northern routes. The Civil War came along and stopped talk of a transcontinental railroad, and only by 1866 was the final decision made to build the transcontinental using the Wyoming route. [34] The central Rockies surveys were abandoned and west-central Colorado was forgotten.

The only lasting evidence of Gunnison's work was that the river he followed into the Uncompaghre Valley was named in his honor. When a railroad was built in the 1880s, it followed the Gunnison survey route exactly. [35]

During the 1850s other federal travellers passed through the Grand River area, often en route between assignments. The first of these was Captain Randolph B. Marcy, who during the Mormon War in 1857, was sent with relief parties to and from Fort Bridger, Wyoming to Fort Union, New Mexico. Along the way the Captain took notice of particular features of the area. He especially noted the difficulty in scaling the Roan Cliffs from the Grand River Valley. [36] The next exploration came two years later when Captain John Maccomb of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers explored the Gateway-Unaweep region of western Colorado and assembled an accurate picture of the Grand River drainage system. [37] Two years earlier a project was undertaken by Lt. J. C. Ives to reach the headwaters of the Grand, but he failed after tracing the river only four hundred miles north from its mouth. [38] The approach of the Civil War led to a temporary cessation of federal exploration in Colorado.

Private explorers also visited western Colorado during the 1840s and 1850s. However, these people left few written records of their exploits. The famed Oregon pioneer, Dr. Marcus Whitman, followed the Grand River to the Gunnison and south along that river on his way to Washington, D.C. to inform President John Tyler on the value and potential of Oregon. He may have been accompanied on this trip by Francis Parkman, but evidence is scanty on that point. [39] Englishman Sir St. George Gore, for whom the Gore Range was named, travelled much of central Colorado's mountains on a hunting expedition during these years. His entourage included mountain men, artists and a variety of camp followers. The expedition left little for posterity except a tremendous record of game slaughtered in the name of sport. [40]

The next concerted effort at exploration occurred with the 1860 expedition of Richard Sopris, who led 14 adventurers across South Park, down the Blue River and into the Roaring Fork Valley. These men were looking for gold during the prospecting craze that took place in Colorado after the 1858 discoveries of gold along Cherry Creek, and the later Gregory Diggings near Central City, Colorado. The Sopris party found nothing of value in the Roaring Fork Valley and returned to the future site of Glenwood Springs. Then they made their way west to the White River, near the place where the town of Meeker, Colorado later arose, before returning to Denver along the Gunnison route of 1853. The only contribution of the expedition was the naming of Mount Sopris, near Carbondale, Colorado, in honor of the group's leader. [41]

The Sopris expedition provided little insight as to the possible developmental value of the Grand Valley and the Roaring Fork region. However, other prospectors like William Gant were also in west-central Colorado observing the land's potential. The information they brought back, combined with the maps and notes that Sopris made, provided an incentive for new prospectors to cross the rugged mountains just east of the head of the Roaring Fork River and try their luck in the Aspen area. [42]

In 1870, Benjamin Graham and six companions crossed the Rockies and found themselves near Rock Creek in the Roaring Fork Valley. This party set up camp and proceeded to prospect for gold. By 1874, they had built a small camp and began to prospect for gold. They built a small fort-like cabin that the Utes burned in 1874. The little group was driven from the Roaring Fork Valley, not soon to return. [43]

Prospectors also worked the Piney (Eagle) Valley looking for gold placers during the 1860s and 1870s. A few promising strikes were made and the news carried back to Denver. For some reason, possibly lack of access, nothing became of these reports. [44] By the mid-1870s prospecting had ceased throughout the district.

The end of the Civil War led to a new and more intensive federal cataloging of west-central Colorado. These efforts were directed toward aiding settlement in the region as well as locating agricultural and mining lands. The reports also gave the prospective settler or investor a general economic picture of the area. The explorers were professional specialists sent out by the U.S. Army and the newly created United States Geologic and Geographic Survey (USGS). The Geologic Survey, part of the Department of the Interior, was especially interested in promoting settlement and other uses of the land, whereas the Army primarily hoped to find sites for posts and roads. [45]

The first of these surveys got underway in 1868 when Major John Wesley Powell started his great exploration of the Grand River and its tributaries. During that year Major Powell assembled his party in Middle Park, where he spent three months organizing the trip. The expedition spent the 1868 season (summer) working its way down the Grand River to its junction with the Green. [46] The Powell effort added significantly to national understanding of the Grand River system and of environmental conditions in the Great Basin. During 1869 Captain Sam Adams claimed to have traced the Grand River from its mouth to source, but these claims were later disproven. [47]

Two other explorations touched the periphery of west-central Colorado a few years after Powell's conquest of the river. From 1867 to 1873, noted Californian naturalist Clarence King was commissioned to survey the Fortieth parallel. He spent 1871, 1872, and 1873 in Colorado, along the northern edge of the region. During the final year of King's effort, Army explorer J.B. Wheeler was in the Elk Mountains looking at possible routes for military roads. [48] These expeditions had very little impact on the development of west-central Colorado. However, another contemporary project did.

In 1873, the great Hayden surveys of Colorado began. Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden, a professor of medicine from Yale University, was selected to lead surveys throughout western Colorado while mapping the balance of the state. Hayden had achieved his reputation in 1869 when he led the Yellowstone Park surveys. Originally, the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was responsible for government surveys. However, in 1869, the U.S. Geological Survey was created and Hayden's Colorado expeditions were the "proving ground" for the infant Geological Survey. [49]

Hayden organized the surveys on a broad basis taking in all types of expertise and using specialists such as geologists, botanists, and topographers. With this group of experts, Hayden, from Denver, sent forth the expeditions on a yearly basis to record the features of western Colorado. In 1873, the Grand Valley was surveyed by J. T. Gardner, Henry Gannett, A. C. Peale, and others. From this survey came basic descriptions of the Grand Valley between Glenwood Springs and Grand Junction. Further, the Roaring Fork Valley, the Crystal River (Rock Creek) country, and the Elk Mountains between Gunnison and Aspen were mapped. [50] The Survey included not only the flora and fauna of the region, but also it drew conclusions as to the economic value of the Grand Valley. The Hayden party(s) found that the Grand River could support agriculture if irrigation was developed, while Battlement Mesa was volcanic ash that could be used for farming. The Hayden survey mentioned that oil shale was common along the Roan Cliffs, while there were natural salt deposits in the Sinbad Valley. [51]

The Hayden Survey made note of these discoveries and pointed out that but for transportation, coal mining could be a major industry in the area. [52]

Interestingly, no mention was made of precious mineral potential in the Grand Valley region. However, elsewhere in the area, investigators found evidences of silver and gold, especially near Aspen, Colorado, and in the Eagle Valley where they observed continuations of the Leadville carbonate belt. [53] Of primary importance, the Hayden surveys did map the Grand Valley by 1876, and for the first time, settlers on the east slope of Colorado realized that there were great possibilities for development in the west.

One of the innovative features of the Hayden project was the fact that they were among the first to use photography as a recording medium. William Henry Jackson, official photographer of the Hayden expeditions, recorded a number of major geographic and historic sites. Among them was the legendary Mount of the Holy Cross, photographed for the first time in August, 1873. [54]

The Hayden surveys were of considerable importance because they provided information that helped open the Grand Valley and its lateral valleys to settlement. These efforts not only provided detailed geographic information, along with careful survey work, but they also showed that western Colorado was ready for Anglo-American development.

From the end of Hayden's great reconnaissance until 1920, west-central Colorado was extensively explored by both private and public expeditions, most of which were interested in enlarging knowledge of the area. These adventurers encountered many of the same problems, especially the rugged, isolated nature of the land, that the earliest Spaniards and mountain men had met.

Cadastral survey of the land was a prerequisite for settlement. This process was contracted out by the General Land Office (GLO). Many of the surveyors covered only the easily accessible areas so that in later years the government had to re-survey the land to resolve numerous conflicts between landholders regarding property lines. [55]

Often following on the heels of the contractors came the first "tourists." These travellers were in search of minerals, science, or simply pleasure. Mining engineers such as B. Clark Wheeler, William Weston, or R. C. Hills were sent out by entrepreneurs to search for new sources of minerals such as coal or silver. [56] Scientific exploration took a step forward in 1900, when Elmer S. Riggs of the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History discovered fossilized remains of dinosaurs in the Morrison formation around Fruita, Colorado. His excavations revealed that a large number of these creatures had once lived in the area. Riggs' finds were considered major discoveries at the time. As early as 1885, local residents took up fossil hunting and searching for old Indian relics so that by 1890 the majority of the known, easily accessible, sites already were plundered. [57] These weekend archaeologists were antedated by campers and other sportsmen who travelled to the mountains near the Continental Divide and recorded experiences for use by later generations. By 1900, much of the region had been examined by these amateur explorers. [58]

At the turn of the century, the Federal government began a new program of geologic survey in western Colorado. This was carried out for three reasons. First, the government sought to establish patterns of geologic relations between formations. Secondly, to legally classify lands as coal or non-coal after reservation of the mineral estate started in 1906; and finally to estimate the potential market value of the various resources, especially coal and oil shale, within the area. At the same time, the U.S. Geologic Survey examined the Grand River for potential reservoir sites. [59] This work was all but finished by 1920.

West-central Colorado was thoroughly explored and mapped by Americans long before the first Euro-American settlers moved into the area. Thanks to the efforts of men like Hayden, farmers and miners on the eastern slope, or indeed any part of the nation, could consider the natural wonders and vast potential of the region. The explorers offered a blueprint for the use of the land and only the Utes barred the way of "civilization" on this frontier.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

co/12/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 31-Oct-2008