______________________________

Ninety Six National Historic Site

CULTURAL OVERVIEW

By Guy Prentice (2003)

______________________________

NATIVE AMERICAN ARCHEOLOGY AND CULTURE HISTORY

Unfortunately, at the time of this writing there is little in the way of readily available published material that summarizes the current state of archeological knowledge on Native American sites found in the

Paleoindian (ca. 9500-8000 B.C.)

The first well-dated evidence of human occupation in the southeastern

Low human population densities and vast lands and resources allowed Paleoindian peoples to be selective in the areas they frequented and the faunal resources they exploited. It is commonly assumed that Paleoindians were specialized, highly mobile foragers that hunted late Pleistocene fauna such as bison, mastodons, caribou, and mammoths (e.g., Chapman 1985), although direct evidence along these lines is meager in the Southeast (cf. Meltzer and Smith 1986;

Current interpretations of the archeological record portray Paleoindian peoples as nomadic, egalitarian bands composed of several nuclear or extended families. Loose social affiliations were probably maintained with other bands (forming larger macrobands) as a means of obtaining mates and exchanging information. Artifacts and sites dating to this period are relatively rare compared to later periods, apparently because of the generally low population densities, and post-depositional processes that have buried or eroded away sites, but also because lithic tool use focused on the utilization of curated, formal tools (Anderson 1990a:180).

At the close of the Pleistocene, the climate became warmer, the glaciers retreated in eastern

Anderson and his colleagues (Anderson 1990a; Anderson and Joseph 1988; Anderson and Sassaman 1996) note that there are, relatively speaking, concentratio

ns of Paleoindian diagnostics (i.e., Clovis, Clovis-like, and Dalton points) in western South Carolina, but Paleoindian sites in Greenville County are rare. Most Paleoindian sites in South Carolina are located within or directly adjacent to major river valleys during the Early and Middle Paleoindian periods with slightly greater numbers of Late Paleoindian (i.e., Dalton) sites occurring in the inter-riverine zones, suggesting a shift in settlement and resource exploitation as a result of changing environments associated with the onset of the Holocene and the replacement of patchy boreal forests and grasslands with a closed canopy oak-hickory forest.

Archaic (ca. 8000 -1000 B.C.)

The Archaic stage in the Southeast is typically interpreted as a period during which: 1) the environment changed from a mixed forest to a closed canopy hardwood forest habitat, and 2) the population of hunter/gatherer bands grew, and 3) the hunting territories of the bands shrank in size (Watson and Carstens 1982; Caldwell 1958; Fowler 1959; Griffin 1967; Jefferies 1990). These changes formed the basis for regional specialization in subsistence, resource utilization, and artifact manufacture.

The Archaic stage has generally been dated from ca. 8000 to 1000 B.C. Within the Archaic stage, three substages are generally recognized: Early Archaic (ca. 8000-6000 B.C.), Middle Archaic (ca. 6000-3000 B.C.), and Late Archaic (ca. 3000-1000 B.C.) which are usually identified on the basis of projectile point styles. The changes in different projectile point styles during the Archaic stage are usually interpreted as reflecting increasing numbers of socially distinct groups and changing subsistence modes. Archaic lifeways have generally been thought of as consisting of semi-nomadic bands that occupied separate territories in which they moved seasonally to take advantage of different natural resources as they ripened or became more easily exploitable within a generally woodland environment.

The Early Archaic (ca. 8000-6000 B.C.) in western South Carolina is characterized by changes in lithic technology where fluted lanceolate forms gave way to side and corner notched forms, including Big Sandy/Taylor (ca. 8000-7000 B.C.) and Palmer/Kirk Corner Notched (ca. 7500-7000 B.C.) types (Michie 1996; Sassaman 1996). In addition, the subsistence base was adjusted with a greater focus on plant foods and small game (with white-tail deer being a favorite prey). The Archaic toolkit was modified accordingly to include tools for plant food preparation and processing (House and Ballenger 1976). Research has shown that Early Archaic sites in the region occur in a wide range of microenvironmental zones, and nonlocal lithic raw materials are common in assemblages (Anderson et al. 1979; Goodyear et al. 1979; Hanson et al. 1978; O’Steen 1983; Anderson and Hanson 1988).

Sometime around 7000 B.C., a number of new projectile point styles exhibiting bifurcate stems appeared in the region. These include MacCorkle (ca. 7000-5800 B.C.),

Corresponding roughly in time with the Hypsithermal (6000-3000 B.C.), the Middle Archaic stage is generally viewed by most archeologists as a period of increased cultural regionalization as a result of growing populations and reduced territorial boundaries. As a result, there was a greater reliance on local raw materials in the manufacture of stone tools, a pattern that is reflected in the South Carolina Piedmont by the contrasting use of crystal quartz and quartzite (more precisely, orthoquartzite) in the manufacture of projectile points and other lithic implements in the Plateau and cherts in the Coastal Plain (Wetmore and Goodyear 1986:20; Blanton and Sassaman 1989; Benson 1995; Sassaman and Anderson 1995). Ground stone implements including atlatl (spearthrower) and axes appear for the first time during this period as do a number of plant processing tools—nutting stones and manos. These, along with the occurrence of storage pits and large quantities of fire-crack rock at some sites suggests there was a greater degree of sedentism and reliance on plant foods compared to previous Early Archaic practices, but a seasonal cycle and frequent movements in search of wild game and plants was still a way of life which has left behind an array of Middle Archaic sites in virtually every environmental setting within South Carolina, a pattern that have been characterized as fluctuating somewhere between short-term specialized extractive sites and longer-term base camps (Coe 1964; House and Ballenger 1976; Elliot 1987). Frequent movement and settlement in a wide array of environmental settings including the inter-riverine hinterlands characterizes the Middle Archaic period in the South Carolina Piedmont.

The Late Archaic (3000-1000 B.C.) was a period of major technological and economic change for

Looking to the adjacent upper Savannah River valley (Anderson and Joseph 1988; Anderson 1994; Ledbetter 1995) and lower Broad River valley regions (Steen and Braley 1994; Benson 1995), (where there are better documented archeological records) for patterns of cultural development that one might expect to see replicated in the Ninety Six area, it is evident that Late Archaic lifestyles in northwestern South Carolina, in many respects, were simply a continuation of previous cultural processes. With increasing population levels and concomitantly shrinking territories, Late Archaic peoples experienced reduced residential mobility with riverine and upland base camps occupied for longer periods of time, but still continued a pattern of intraregional movements which accommodated the exploitation of natural resources as they became seasonally available at outlying temporary extractive camps (Sassaman and Anderson 1995; Sassaman et al. 1990).

Projectile point styles continued to change over time, although the exact timing of certain types remains somewhat ambiguous. Large Savannah River Stemmed points that began to appear near the close of the Middle Archaic were probably made throughout the Late Archaic (Sassaman and Anderson 1995:110; House and Ballenger 1976). By the end of the Late Archaic, quartz was no longer the nearly exclusive material of choice in manufacturing stone tools; locally available metavolcanics (e.g., argillite, rhyolite, and slate) now comprised a noticeable portion of the lithic assemblage (Novick 1980). Smaller varieties of Savannah River Stemmed, Ledbetter Stemmed, and Otarre Stemmed (Keel 1976; Sassaman and Anderson 1995) are common projectile point types for the period (3000-1000 B.C.).

Fiber-tempered Stallings and sand-tempered Thom's Creek ceramics are firmly dated to the latter three-quarters (i.e., 2500-1000 B.C.) of the Late Archaic, with a beginning date of 2200 B.C., currently being the best estimate for the introduction of pottery use in the Carolinas (Anderson et al. 1996:31). Their use, however, is largely confined to the Coastal Plain and the major river valleys of the lower

One of the more interesting practices that appeared during the Late Archaic period in

Perhaps what would become the most significant change in the lifestyles of some Archaic stage peoples was the adoption of plant horticulture starting sometime near the beginning of the Late Archaic period in some areas of the Southeast. The earliest planted crops included cucurbits (squashes and gourds), sunflower, sumpweed, and chenopod (Crites 1991; Smith 1989; Gremillion 1993). Currently, there is no direct evidence to support the proposition that Late Archaic peoples in the Ninety Six area were horticulturalists; but there is good evidence that peoples in nearby eastern Tennessee were planting gardens using native plant species (Chapman and Shea 1981; Gremillion 1993; Wetmore and Goodyear 1986) and it has been suggested that the adoption of pottery may have been commonly associated with the adoption of plant husbandry. Although the arrival of horticulture signals the beginning of new human/plant relationships in the Southeast, it appears that horticulture did not contribute a significant portion of the diet until well into Woodland times.

The Woodland period in South Carolina has also be divided into Early (ca. 1000-500 B.C. ), Middle (ca. 500 B.C.-A.D. 500), and Late (A.D. 500-1000) periods with certain ceramic types and projectile point forms used as general time markers for each of these periods. Overall, this major time period has been characterized by the establishment of semi-permanent or permanent villages occupied much if not all of the year, widespread adoption of pottery use, construction of mounds, and elaboration of an incipient system of horticulture (Struever and Vickery 1973; Smith 1986, 1989).

Again, with respect to the Woodland period, the Ninety Six area lies between better known cultural regions of South Carolina—the South Carolina Midlands, the Upper Savannah River Valley, and the South Carolina upper Piedmont. Near the South Carolina Fall Line,

Early

Various sources (e.g., Anderson et al. 1979; Wood et al. 1986; Hanson and DePratter 1985; Sassaman 1993; Steen and Braley 1994; Ledbetter 1995) identify Thom’s Creek, Refuge, and Deptford wares as forming a basically successional Woodland ceramic sequence for the Georgia-South Carolina Coastal Plain region as a whole with each pottery series slowly evolving into the other during a roughly 700 year time span (ca. 1000-300 B.C.). Currently recognized types included in the three major ceramic series include: Thom’s Creek Plain, Thom's Creek Punctate, Thom's Creek Simple Stamped, Thom's Creek Incised, Refuge Plain, Refuge Simple Stamped, Refuge Punctate, Refuge Dentate Stamped, Refuge Incised, Deptford Plain, Deptford Simple Stamped, Deptford Check Stamped, Deptford Linear Check Stamped, and Deptford Bold Check Stamped (Caldwell and Waring 1968; Waring and Holder 1968; Waring 1968). These types are apparently rare, however, for the middle to upper South Carolina Piedmont (Benson 1995:19) wherein the Ninety Six National Historic Site is situated, and it appears that fabric impressed and cordmarked sand-tempered wares similar to the Swannanoa series may be more characteristic of Early Woodland sites in the Ninety Six area. Nevertheless, a recounting of the Refuge ceramic sequence is provided below in the remote possibility that such wares are found within the vicinity of the park, since Thom’s Creek Punctate pottery has been reported by Rodeffer et al. (1979:332-333) for two sites in Greenwood County.

In the

Refuge Simple Stamped are primarily distinguished from Deptford Simple Stamped on the basis of execution; the former is generally randomly and sloppily decorated with sharp and broad edged implements that produced V- and U-shaped impressions while the latter is neatly applied in parallel or crossed lines. Refuge pottery is also typically thicker and tempered with coarser sand/grit than Deptford pottery (Waring 1968:200).

According to Anderson and Joseph (1988:208-209), the Early Woodland period in the upper Savannah River drainage is primarily marked by the appearance of sand-tempered fabric marked ceramics which they viewed comparable to Dunlap Fabric Marked and as a fairly “unambiguous marker of an Early Woodland component” (Anderson and Joseph 1988:209) for the eastern Georgia/western South Carolina Piedmont. Early Woodland sites, however, are apparently rare in the mid to upper South Carolina Piedmont (cf. Benson 1995:20), making any generalizations regarding Early Woodland cultural patterns tenuous at best, although Rodeffer and his associates (Rodeffer et al. 1979:50-51, 332-333) variously report having found somewhere between 19 and 23 Early Woodland sites in Greenwood County based on the recovery of a total of about 40 sherds (plain, simple stamped, and fabric impressed) that they assigned to the Swannanoa series. An additional four dozen or so

Dating of the Swannanoa phase was originally thought to be sometime around 700-200 B.C. (Keel 1976:17) but more recently the beginning date has been pushed back to ca. 1000 B.C. based on radiocarbon dates obtained at the Phipps Bend site (Eastman 1994; Ward and Davis 1999:142). The earlier appearance of cordmarked and fabric marked wares during the Swannanoa phase in western North Carolina is in accordance with Anderson and Joseph’s (1988) hypothesis that these are the earliest decorative modes among Early Woodland pottery types (Dunlap Fabric Marked and Deptford Cord Marked) in the upper Savannah River drainage, and that the introduction of check stamping and simple stamping as decorative techniques occurred sometime just before the Middle Woodland period.

Rucker’s Bottom, the only extensively excavated site in the upper Savannah River drainage containing a sizeable Early Woodland component, has also produced numerous small-stemmed points similar to terminal Archaic/Early Woodland stemmed types (i.e., Otarre, Plott, Swannanoa, and Gypsy Stemmed types) found elsewhere in the Carolina Piedmont region. Early Woodland Dunlap Fabric Marked pottery was also found in association with a large quartz “Yadkin-like” triangular point at the Big Generostee Creek (38ABN126) site (Anderson and Joseph 1988:213). The presence of medium-large triangular points (Badin, Yadkin) points in the upper Piedmont probably occurs during the later portion of the Early Woodland period (Benson 1995:20), however, as these point types appear roughly comparable to the Transylvania and Garden Creek Triangular points associated with Keel’s (1976) original Swannanoa (ca. 600-200 B.C.) and Pigeon (ca. 200 B.C. -A.D. 200) phases, respectively, in western North Carolina (Keel 1976:17, 130, 224; Anderson and Joseph 1988:219). Surprisingly, there were few instances of sand-tempered cordmarked ceramics represented among the tested

Middle

The initial Middle Woodland ceramic assemblages found in the upper Savannah River drainage appear to consist of combinations of sand and grit tempered Dunlap and Deptford series wares that eventually give way to the finer tempered and smoother finished Cartersville series sometime around 300-200 B.C. (Anderson and Joseph 1988:230). While the appearance of Deptford check stamped, linear check stamped and simple stamped pottery sometime around 600-500 B.C. (Anderson [editor] 1996) is generally viewed as signaling the arrival of Middle Woodland times in much of the Carolinas, these pottery types appear to have carried over into the Late Woodland and perhaps Mississippian times as well (Anderson 1985:52) making them somewhat less reliable for assigning temporal affiliations to sites based on their presence alone. Earlier (ca. 200 B.C.-A.D. 400) and later (A.D. 400-600) Cartersville ceramic assemblages are now recognized for the upper Savannah River region, the former characterized by plain, simple stamped, check stamped, and linear check stamped surface treatments, the latter by plain, simple stamped and brushed finishes (Anderson and Joseph 1988:230). According to Anderson and Joseph (1988), large triangular points with indented bases known as Yadkin Large Triangular (or more simply Yadkin) points are viewed as a good Middle Woodland indicator for the entire length of the period.

Sites with light Cartersville/Deptford components have been found at a few locations in the South Carolina Piedmont, including Abbeville and

The Pigeon phase (ca. 200 B.C.-A.D. 200) in western

The following Connestee phase (ca. A.D. 200-600) assemblage is characterized by Keel (1976) as being dominated by Connestee Brushed, Connestee Cordmarked, Connestee Simple Stamped, and Connestee Plain, with minor amounts of Connestee Check Stamped and Connestee Fabric Impressed, all of which were tempered with fine- to medium-sized sand and occasionally small amounts of crushed quartz. Decorated wares sometimes had plain surfaces on the necks of the vessels, which were generally in the form of conoidal jars, hemispherical bowls and flat-bottomed jars with tetrapodal supports (Keel 1976:247-254). A date range of A.D. 200-600 was originally given for the phase (Keel 1976:19), with the caveat that an hypothesized transitional phase presumably followed that eventually evolved into the Pisgah phase sometime around A.D. 1000. Since then, the proposed terminal date for Connestee has been pushed forward to ca. A.D. 800 (Ward and Davis 1999:146) and a tentative Late Connestee period has since been inserted into the chronological framework of western

Connestee series ceramics have been reported at a number of sites in

According to Chapman (2000), Pigeon (check stamped, simple stamped, and brushed types) and Cartersville (cordmarked, simple stamped, and check stamped types) are the primary Middle Woodland pottery series found in the lower Enoree River drainage of adjacent Newberry County, with Connestee wares also appearing in relatively few numbers during the last half (ca. A.D. 50-600) of the period. Chapman (2000:23) is of the opinion that this represents “the periphery of its [Connestee] influence” (Chapman 2000:23).

Connestee sites appear to be somewhat larger and more numerous in riverine floodplain and terrace settings than their earlier counterparts, which has been interpreted by some as indicative of increased sedentism (Purrington 1983:139), but use of upland sites also persists, indicating a continued reliance on the natural resources (e.g., nuts, deer, turkey) found in these woodland settings. The Connestee phase is also marked by the first appearance of earthen mounds in the Appalachian Summit, a development that is probably linked to Connestee participation in the Hopewell Interaction Sphere and the provisioning of mica from the Appalachian Summit region to Hopewellian cultures to the west (Chapman and Keel 1979).

Late

Any attempts at construing Late Woodland lifeways in Greenwood County and the upper South Carolina Piedmont at the present time are hampered by a lack of well understood cultural analogs in the adjacent culture areas. The Late Woodland time period is generally viewed by archeologists as the period in which the economic and social underpinnings that later led to the development of Mississippian culture were established by the appearance of fairly permanent village sites and the widespread adoption of maize agriculture, although it appears that it remained a minor contribution to the overall Late Woodland diet. The degree to which this characterization applies to the upper South Carolina Piedmont remains very much in doubt, however, because well documented Late Woodland occupations have yet to be identified in the immediate or surrounding areas. This conundrum is probably at least partially due to the proposition that locally produced Late Woodland pottery types in the upper South Carolina Piedmont are so similar to Middle Woodland types that Late Woodland components at many sites have simply not been recognized. For example, fine sand-tempered, simple stamped wares (e.g., Connestee Simple Stamped, Santee Simple Stamped, Camden Simple Stamped) long considered Middle Woodland pottery types have recently been recognized as also being Late Woodland/Mississippian (ca. A.D. 500-1400) pottery forms for a large area extending from central Georgia to northern coastal North Carolina (Anderson [editor] 1996:20; Ward and Davis 1999:157-158). Similarly, projectile point types of the period consist primarily of medium to small triangular forms (Haywood Triangular, Pisgah Triangular) comparable to Hamilton Incurvate and Madison types (Keel 1976:132-133; Justice 1987:224-229) which also span the entire Late Woodland to Mississippian time frame. The paucity of well dated ceramic trade wares has also hindered the recognition of Late Woodland occupations in the region.

The readily identifiable grog-tempered pottery of the

Mississippian Period (ca. A.D. 1000-1600)

During the first six centuries of the most recently concluded millenium, the upper South Carolina Piedmont was encompassed within a wide reaching cultural manifestation that has come to be referred to by archeologists as South Appalachian Mississippian (Ferguson 1971), which is a regional expression of the Mississippian cultural stage. The Mississippian stage is generally characterized as the time in

The adoption of an economic system with a major emphasis on horticulture for food production had great ramifications with respect to Mississippian settlement patterns. The majority of Mississippian villages were settled along the fertile river bottoms of major tributaries where light alluvial soils conducive to hoe tilling methods made horticulture most productive. Within these fertile valleys Mississippian peoples planted their gardens of maize, squash, sunflowers, and other domesticated plants. They also fished in the nearby river, lakes, and streams and made regular trips into the uplands to gather nuts and hunt deer, turkey, squirrel, and other small game.

The rise of Mississippian cultures was also intimately tied to the development of chiefdoms. Chiefdoms, with their highly structured social and economic relationships, permitted larger numbers of people to share the greater productive potential of maize agriculture while also disbursing the potential risks which a major crop failure would bring to any one portion of the larger society. The ability to redirect surpluses from one part of the chiefdom to another portion which had suffered lower productive success or crop loss was an economic advantage chiefdoms enjoyed over less regimented social organizations. The political and economic nature of chiefdoms, however, resulted in persistent competition as individuals vied for the few highest positions in the chiefdom in order to benefit from the greater affluence and prestige that were afforded to the elite. Continual attempts to expand the influence of the chiefdom and bring neighboring groups under economic and political subservience, rapid increases in population numbers, and a preference for limited floodplain areas for farming led to regular armed conflict, another major factor which also affected settlement placement and site plan.

Although the development of South Appalachian and other Mississippian cultures from their Late Woodland cultural forebearers clearly was a process that brought intertribal competition to the forefront, it was also a period of sharing and dissemination of new ideas and beliefs, new ways of cooperation, and new ways of coping with the uncertainties of everyday life. Archeologists, trying to understand this process have subdivided South Appalachian Mississippian history into three major substages that reflect the initial amalgamation of Mississippian cultures into simple chiefdoms (Early Mississippian), the rise of complex chiefdoms that exerted broad-reaching political influences (Middle Mississippian) and the full maturation of Mississippian lifestyles such as those encountered by the first European explorers (Late Mississippian). In the South Appalachian Mississippian cultural sphere, these three substages have been roughly equated with Etowah,

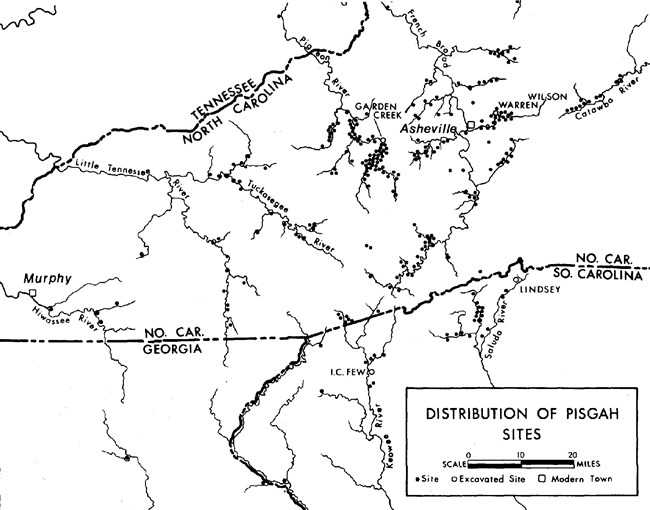

The archeological vestiges of these three successive Mississippian substages or cultures are most recognizable today by the distinctively made ceramics that were with the passage of time adopted by the peoples living in northeastern

The investigation of Mississippian culture in the area around Ninety Six National Historic Site has been made somewhat difficult by the relative paucity of documented Mississippian sites in

The paucity of a demonstrable Mississippian presence in the

The Mississippian mound centers located along the lower Broad River contain ceramics that show minor similarities with the Lamar (Irene) complexes of the Savannah River area but show greatest affinities to the Pee Dee and Pisgah culture areas to the east and north, respectively (Teague 1979:63; Benson 1995:12), and are believed to have been abandoned as political centers by sometime around A.D. 1400 (DePratter 1989; Hudson et al. 1990), thereby creating an even larger western buffer zone for the Mississippian chiefdoms occupying the Wateree/Catawba drainage during the remainder of the precolumbian and early contact era (i.e., A.D. 1400-1700). In addition,

This buffer zone was also apparently respected by the earlier Mississippian peoples that occupied sites like Lindsey Mound along the upper

In all likelihood then, the Ninety Six and

The appearance of Woodstock Complicated Stamped ceramics, which is currently viewed as the initial arrival of Mississippian traits in the Savannah River drainage of northwest Georgia and South Carolina (Anderson 1994:375), have been rarely encountered in the upper Savannah River area, suggesting that the first century of the second millenium A.D. may have been a time of protracted Mississippian cultural coalescence and/or perhaps lower population densities for the region. Each of the subsequent Mississippian phases are well documented, however, and are distinguished on the basis of changes in ceramic assemblages as well as shifts in settlement and mortuary patterns.

The Jarrett phase (ca. A.D. 1100-1200) is characterized by the appearance of Etowah Complicated Stamped, check stamped, and red filmed pottery (Anderson 1994:375). The complicated stamped designs during this phase consist primarily of nested diamond motifs with corncob impressions occurring in low numbers along the necks and upper shoulders of some vessels. The majority of sites dating to this period appear to be scattered homesteads, with perhaps the Clyde Gulley site representing a small village or large hamlet during this phase. Two single mound centers, Chauga and Tugalo, were also established near the headwaters of the

The Beaverdam phase (ca. A.D. 1200-1300) sees a decline in the numbers of Etowah Complicated Stamped ceramics and the disappearance of red filmed pottery. Check stamping increases and Savannah Complicated Stamped appears, with concentric circles being the most common motif. There is an abrupt shift in settlement patterns with the establishment of new ceremonial sites, hamlets, and farmsteads within the settlement hierarchy. The Chauga and Tugalo sites were apparently abandoned as ceremonial centers, and ceremonial activities were established downstream at the Beaverdam Creek, Tate and Rembert mound sites. It is possible that by the end of the Beaverdam phase Rembert was already established as a multiple mound center and that the single mound Beaverdam Creek and Tate sites were the residences of chieftains who were subservient to a paramount chief living at Rembert. Maize agriculture was also well-established by this time, although its contribution to the overall diet is still open to question.

By the Rembert phase (ca. A.D. 1350-1450), the Rembert Mound group with its five platform mounds had become the premier ceremonial center for the entire upper

During the ensuing Tugalo phase (ca. A.D. 1450-1600), the instabilities inherent within the socioeconomic structure of the Savannah River chiefdoms, made even more tenuous by an extended period of lower than normal rainfall within the region, coupled with competition from surrounding Mississippian polities resulted in the political collapse of the societies occupying the middle and lower Savannah River basin, which appears to have been largely unpopulated during this period. Only the upper reaches of the

Once again, changes in the ceramic assemblage are also evident within this final precolumbian phase. Lamar Complicated Stamped and Lamar Incised pottery retain their popularity during the Tugalo phase (ca. A.D. 1450-1600), but the stamping on the former is generally executed less carefully and the designs are more complicated while the designs on the latter ware are typically composed of a greater number of narrower lines than the preceding phase. Red filming appears once again as a minority ware (Anderson 1994:376).

Early Contact Period (ca. A.D. 1540-1700)

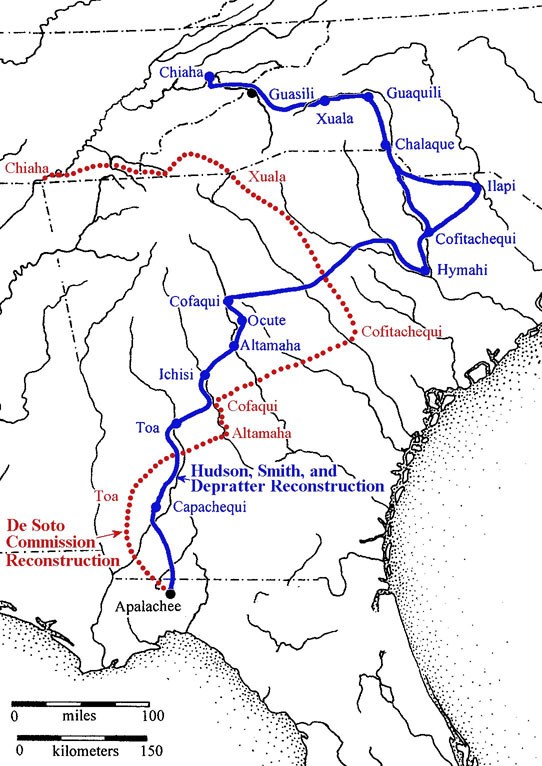

At the time of the

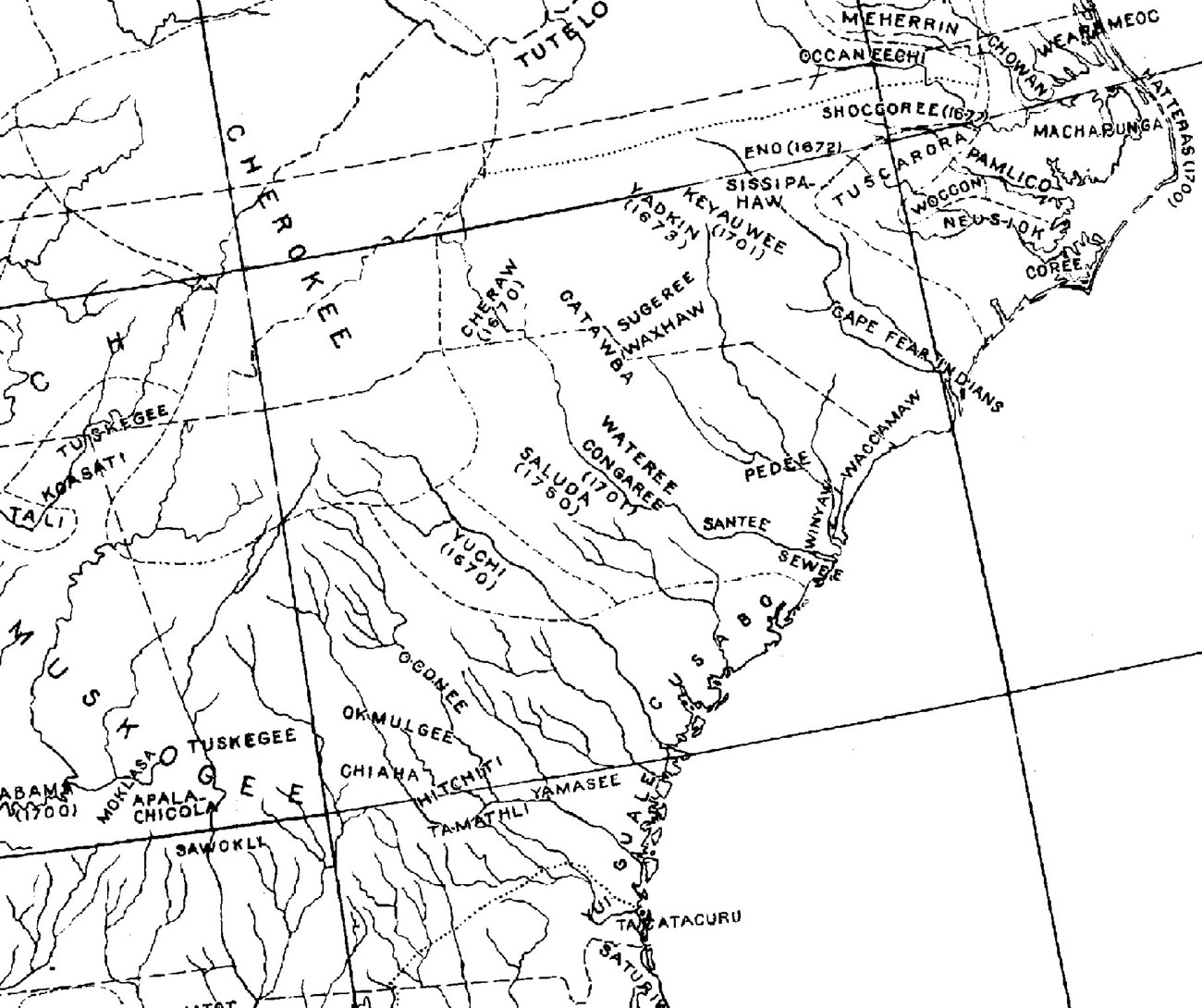

Although Cofitachequi and Ocute were powerful tribes at the time of the De Soto entrada, their political prominence and cultural existence were doomed along with those of their neighboring brethren with the arrival of the first Europeans. At the time of first European contact, South Carolina was inhabited by a number of Indian tribes that shared a Late Mississippian (Lamar) way of life, but were distinctive in terms of cultural and linguistic traits. Three major linguistic families were represented in 16th century South Carolina: Siouan, Muskhogean, and Iroquoian. The Piedmont and northern two-thirds of the Coastal Plain of South Carolina were occupied primarily by Siouan linguistic groups (Image 3) that included the Catawba, Iswa, Shakori, Wateree, Santee, Congaree, Pee Dee, Waccamaw and Winyaw (Swanton 1946, 1952), although if Swanton (1946:46), Milling (1969:66), and others are correct in their linguistic assessments, the Cofitachequi were apparently Muskhogean speakers. Muskhogean related peoples living in South Carolina during the 16th century consisted primarily of the Cusabo who occupied the Coastal Plain between Charleston Harbor and the Savannah River and were closely related to the Guale of coastal Georgia (Swanton 1952:94; Bushnell 1994:60). At the time of European contact, the Appalachian Summit or Blue Ridge Province of North and South Carolina was part of the territory inhabited by the Cherokee, a large Iroquoian-speaking group with principal settlements mainly distributed along the upper Savannah, Hiwassee, and Little Tennessee River drainages (Schroedl 2000; Ward and Davis 1999:266). Their somewhat distant relationship to other members of the Iroquoian language family and a Cherokee legend of migration from the northeast (Swanton 1952:221) has led some scholars to propose that the ancestors of the Cherokee moved to the Southern Appalachians from the Iroquoian heartland many centuries before early Spanish explorers entered the region and briefly encountered Cherokee peoples for the first time during the 16th and 17th centuries. The scant information available from these earliest encounters and the vagaries of the limited archeological evidence have left the prior history of the Cherokee people very much open to debate, and it is not until the English arrived on the continent in the mid-18th century, that an extensive record of Cherokee culture becomes available.

A Brief History of the Cherokee, 1674-1842

One of the earliest English accounts that unambiguously mention the Cherokee occurs in Henry Woodward’s description of his visit among the Westo (Chichimeco) in 1674 (Crane 1929:16; Swanton 1946:111). The “Chorakae” peoples Woodward referred to in his 1674 narrative were said to inhabit the headwaters region of the Savannah River and to be the enemies of the Westo who then occupied the middle Savannah drainage. The Cherokee peoples that were encountered by the English as they first began to settle and explore the Carolinas were found distributed in five geographically distinct areas, the largest geographic group being the Lower Towns settlements located along the upper drainages of the Chattahoochee and Savannah River in northwestern South Carolina and northeastern Georgia (Schroedl 2000). The inhabitants in this area spoke a distinct Cherokee dialect known as Elati (Mooney 1900), and lived in a dozen or so politically independent towns that include the archeologically investigated sites of Chattooga, Estatoe, Tugalo, Chauga, and Keowee. Contacts between the Cherokee and the earliest English colonists in coastal South Carolina were limited at first due to the intervening presence of the frequently warring Westo who had come to occupy the middle Savannah River area and counted the Cherokee among their many enemies. After the defeat of the Westo by the South Carolinians in 1681, English contacts with the Cherokee and other western tribes became a regular occurrence as the English pursued their policy of establishing trade relations with the interior tribes.Trade formed the primary basis for Cherokee-British relations during these early years with British traders frequently taking up residence in the Cherokee towns where they provided their hosts with guns, axes, hoes, knives, blankets, and other utilitarian items in exchange for deerskins and, more importantly, Indian slaves. While they benefited materially from their trading relationships with the British, the Cherokee also suffered greatly as a result of increased intertribal warfare directly attributable to the slave trade. In the century following the establishment of Charleston, S.C. in 1670, the Cherokee were involved in numerous conflicts with the Guale, Westo, Shawnee, Catawba, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Congaree, Creek, and Tuscarora, often with the encouragement of the British as a means of providing captives for the slave market (Crane 1929:24, 40, 109-120, 138-139; Swanton 1946:111-112; Swanton 1952:221-222). The casualties of intertribal warfare paled in comparison, however, to the losses suffered from deadly epidemics caused by the introduction of European diseases for which the Cherokee had little immunity. In 1738, for example, a smallpox epidemic devastated the Cherokee, reducing their population of some 20,000 people by nearly half. As a result, many of the Lower towns, particularly those in northwest

Cherokee relations with the British were not always on an entirely friendly basis either. Charges of thievery and unfair trading practices including the unlawful taking of slaves were frequently raised by the Cherokee before

At the outbreak of the American Revolution, the Cherokee again remained loyal to the British and suffered the consequences of numerous American military raids into Cherokee territory. In 1776, General Griffith Rutherford and Colonel William Moore led the North Carolina militia in attacks against the Middle, Valley, and Outer Towns while South Carolina forces led by Colonel Andrew Williamson attacked the Lower Towns (Schroedl 2000:221-222). Finally, in November of 1776, a

In the ensuing years some Cherokee tried to maintain their traditional ways of life but many chose instead to adopt Euroamerican ways and agrarian lifestyles with the encouragement of the new

A Brief History of the Catawba

The Catawba were one of the Siouan-speaking tribes that occupied the upper Piedmont area during the time of the early Spanish expeditions into South Carolina during the mid 16th century. They were apparently closely related to the Issa (Ysa, Iswa) that were encountered during Pardo’s expedition into the South Carolina interior in 1566-67. When John Lederer entered the North Carolina interior from Virginia in 1670, he too met the Catawba, referring to them as Ushery (Lederer 1672; Alvord and Bidgood 1912). What little is known regarding the Catawba way of life shortly after the arrival of the English to the Carolinas is derived largely from the writings of John Lawson (1709), who explored the Piedmont territory and visited the Catawba in 1701. When Lawson encountered the Catawba (“Kadapau”) at the beginning of the 18th century, they were described as a distinct group, living less than a day’s travel from the Iswa (“Esaws”) (Lawson 1709:43) shown on Lawson’s map of the Carolinas as being located at the headwaters of the “West Branch” of the “Clarendon River” (i.e., the Catawba River); but as native populations in the Carolinas rapidly declined as a result of war and epidemic disease, the Catawba later merged with the Iswa and with the remnants of many other Siouan-speaking groups in the region. The Catawba were quick to make friends with the English, and remained faithful allies during most of the 18th century, except for a brief period in 1715 in which they joined the Yamassee in their fight against the Carolinians. Their relationships with other neighboring tribes were not as friendly, however, as they alternately waged wars against the Shawnee , Delaware , Yuchi, Iroquois, Mobile , and Tuscarora Indians before they turned to join the Yamassee during their uprising in opposition to the slave-raiding of the Carolinians in 1715.The Yamassee, Catawba, and their other native allies (Congaree, Santee, Sugeree, Wateree, Waxhaw) enjoyed some early successes, capturing several British forts and taking the lives of an estimated 200-400 colonists (Swanton 1952:115; Steen and Braley 1994:26), but the Carolinians eventually prevailed, exacting a terrible revenge of death and enslavement that virtually eliminated many native groups. The Catawba had sued for peace earlier than the other participating tribes (Swanton 1952:91) and therefore survived to absorb many of the remaining refugees, including the Iswa, Congaree,

Almost immediately, the Catawba reservation suffered from the encroachment of the

After the Revolutionary War, the

EUROPEAN COLONIZATION OF

Prior to the settlement of the English colony at Charles Town (Charleston, S.C.) in 1670, the South Carolina coast had been claimed and defended by the Spanish against rival European powers for over one and a quarter centuries. During that time, they attempted to bring the lands and the native peoples who already occupied the country the Spaniards called “La

The earliest documented contact between the Spanish and the Indians of South Carolina apparently occurred in 1521 when two Spanish ships sailing along the Georgia/South Carolina coast stopped at the mouth of a major river, brought on board some 70 natives and carried them off to Santa Domingo. Among the 70 was a member of the Shakori tribe known as Francisco of Chicora who became a servant of the man who had initiated the 1521 Spanish expedition that led to his capture, Lucas Vasquez de Ayllón. During his stay on Santa Domingo, Francisco of Chicora meet the historian Peter Martyr de Anghierra, who obtained from him an account of the Siouan peoples who apparently inhabited portions of the

The first attempt by the Spanish to settle in

Spanish Defense Against the French and English, 1560-1670

Spanish claim to

Following the renewed colonization efforts initiated by Laudonnière, King Phillip II ordered Captain Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to find the colony and destroy it. Assembling a force of over 1000 men and ten ships, Menéndez immediately set forth to drive the French out of

Determined to prevent the Spanish from establishing a foothold in the area, Ribault decided to attack the Spanish with approximately 600 of his best men, using the ships just arrived from France—and not yet unloaded—leaving a nominal force of just over 200 behind to defend Fort Caroline. When Ribault and his fleet arrived off the bar at

On the morning of

That same year, Menéndez built Fort San Pedro on

Toward this end, Captain Francisco Fernandez de Ecija was dispatched from St. Augustine in 1605 and again in 1609 to search for an English colony that was said to be located somewhere along the coast of the Carolinas (Hann 1988), but failed in both instances to find any evidence of an English presence. Similar searches were conducted some years later under the command of Pedro de Torres, who led a small force of Spaniards and Indians in search of alleged European interlopers but failed on successive attempts in 1627 and 1628 to find any evidence of foreign intruders. Two decades earlier, of course, the English had already established a permanent foothold in the colony of

At first, many of the Indians of Virginia and

The Yamassee were a Muskhogean-speaking peoples who probably lived in the “Province of Altamaha” that was encountered by the members of the De Soto entrada as they passed through northeast Georgia in 1540 (Swanton 1952:115). They remained relatively unnoticed by the Spanish and English occupying the

Seven years earlier, in 1663, King Charles II granted a charter for a new colony south of Virginia to eight English noblemen¾Lord John Berkeley; Sir William Berkeley; Sir George Carteret; Sir John Colleton; Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper; Lord William Craven; Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon; and George Monck, Duke of Albemarle¾who had helped him to gain the throne of England. The eight “Lords Proprietors” were confident they could lure immigrants to settle their new colony not only from

The English Colonize

So it was with great expectation that three English ships¾the

Although the first few years in Charles Town were arduous for the early colony’s inhabitants, the community quickly prospered and grew as a important seaport. The nearby forests yielded rich timber and naval stores such as pitch and tar for the shipping industry. Wealthy colonists, many of them Barbadians, employed African and Indian slaves on their extensive plantations to grow indigo, cattle, tobacco and rice for export. Those involved in the lucrative fur and slave trades prospered. This general prosperity did not extend to the coffers of the Lord Proprietors, however, who profited little from the

As the English in

With the conclusion of the Westo War in 1681, the path was now open for the English to extend their influence westward by establishing trading relations with the Cherokee and the Creeks, thereby adding to the rancor of the Spanish who wished to keep the British out (Hann 1988:188-189). Large numbers of the Lower Creeks (Apalachicola) living along the Chattahoochee River began to relocate to the Fall Line region near the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers to take advantage of closer trade opportunities with the Charles Town colonists, and by the early 1690s many had settled near what is now Macon, Georgia and along the lower Savannah River (Worth 2000:279). The Charles Town traders welcomed the arrival of the Creek, who, according to one official report consumed a “great quantity of English Goods” (Colonial Office Papers 5:1264, cited in Crane 1929:37).

In the year prior to the conclusion of the Westo War, the prospering English community at Albemarle Point (Old Charles Town), now boasting a population of some 1200 people, moved across the river to the more defensible neck of land between the Ashley and Cooper rivers, where the new capitol of Charles Town had been laid out following a square grid. Persecution in

But this affront paled in comparison with an attack that was carried out in early spring of the same year by a fleet of English and French pirates led by Monsieur de Grammont. Denied his original goal of plundering

Meanwhile, the Scots led by Lord Cardross (Henry Erskine) had settled Stuart’s Town on

Reports of the Spanish attack on Stuart’s Town soon reached

This and other transgressions against the Indians, sparked the Yamassee War which ultimately had such disastrous consequences for those who chose to bear arms against the English colonists. Before they were crushed, the Yamassee and their other Indian allies (Creeks, etc.) killed hundreds of Carolinians before the English militia and their Indian allies (Cherokee, Cusabo, etc.) crushed the insurrection by massacring and capturing thousands of Yamassee, Congaree, Santee, Sewee, Wateree, Apalachee and others (Swanton 1952:91-104). The vanquished who were not killed or captured and sold into slavery either surrendered and pledged future loyalty to the English or sought protection by fleeing to western Georgia and Alabama and to what little remained of Spanish controlled Florida. The Yamassee were among those who chose the last option, and some 500 are said to have settled near

The Yamassee War and the routing of the Yamassee, Apalachee, Congaree, and other native groups that had previously occupied eastern Georgia and South Carolina prior to 1716 now left the English colony’s Indian trade disrupted and their southwestern frontier deserted with no Indian allies to act as a buffer between them and their not so distant European adversaries, the French in Alabama and the Spanish in Florida. In the geopolitical vacuum that was thus created, the confederation of native groups that made up the Upper and Lower Creek towns that occupied the Alabama and Chattahoochee River drainages now found themselves being courted on all sides by the English, French, and Spanish as the European powers attempted to bring the various remaining Indian tribes in the region under their sphere of influence. English attempts to draw the dispelled Indian groups, including Creek and Yamassee, back toward

The Yamassee War had another unforeseen consequence for the Lord Proprietors of

While the Carolinians worked toward strengthening their colony’s military preparedness following the Yamassee War, the Spanish did likewise. In their recruitment of refugee Indian groups, the Spanish were successful in getting some of the displaced Apalachee to relocate near the presidio of

Although they were referred to as the “Creek Indians” by the English, the use of this singular term greatly glossed over what was actually an amalgam of fairly autonomous Muskogean speaking peoples who politically and ethnically distinguished themselves from one another on the basis of the talwa (“town”) they belonged to (Paredes and Plante 1975; Waselkov and Smith 2000; Worth 2000). As the crises that affected the Creek Indians grew during the late 17th and early 18th century, the loosely aligned towns sometimes acted together in dealing with the competing European powers, but at other times they conducted their affairs quite independent of one another. In their various dealings with the Europeans, the Creek seem to have made little secret of the fact that obtaining European trade goods and ammunition were among their primary purposes in establishing political alliances (Hann 1988:312; Bushnell 1994), and in this regard the English traders soon proved most able to provide the requisite supplies. English relations with the Creeks were complicated, however, by the continued state of hostilities that existed between the Creeks and the Cherokee following the Yamassee War.

The Cherokees had fought on the side of the British against the Creeks during the Yamassee War, and the Creeks and the Cherokees remained bitter foes toward one another even after both groups has established relatively peaceful relations with the British. Although some English colonists welcomed the rivalry that existed between the Creek and Cherokee as a means of preventing their uniting together to form another Indian uprising against the colonists, ultimately, the English viewed the Creek and Cherokee rivalry as a threat to English interests and tried to establish peace between them, but were unable to get representatives of the Upper and Lower Creeks to smoke the peace pipe with the Cherokee until January 1727 (Crane 1929:269-270). Some factions of the Upper and Lower Creeks remained at odds with the English, however, particularly those who were being courted by the French operating out of

During the time the English colonists were trying to end the hostilities between the Cherokee and the Creek, English slave traders were pursuing friendly relations among the Chickasaw and Choctaw, who were also hostile toward one another. English overtures among the Chickasaw were more successful, which led to Chickasaw attacks on the

At the dawn of the third decade of the 1700s, the English colonists of

The Founding of Ninety Six, 1730-1760

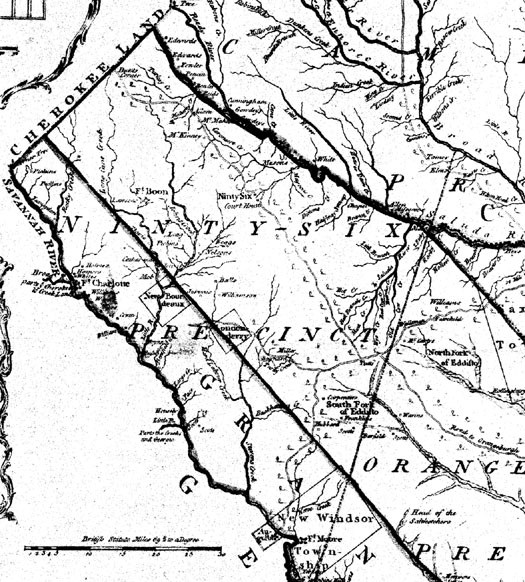

The Cherokee Path, the most direct route between

The people who first settled in the vicinity of Ninety Six in the 1730s initially had no formal claims to the land. Thomas Brown, a trader who had resided previously at the Congarees, was the first to seek formal title to a tract of land, 250 acres, at Ninety Six. However, his 1736 claim had not been settled by the time of his death in 1737 (Cann 1974:2).

Ten years after Thomas Brown submitted his claim at Ninety Six, agents made a request to the colonial assembly to encourage British subjects to settle near Ninety Six by offering all new immigrants an exemption from all provincial taxes, except those exacted on slaves. At Governor James Glen’s recommendation, the assembly voted to suspend the specified taxes to all northern frontier residents for a period of 15 years.

To preempt any negative reactions that the Cherokee might have to an influx of new settlers into the high country, Governor Glen met with 61 Cherokee headmen at Ninety Six on

With the promise of peace, there came an influx of land speculators to the Ninety Six area. Foremost among them was John Hamilton who in 1749 acquired title to 200,000 acres just south of the Ninety Six area, and commissioned a survey in 1751 in order to subdivide and sell it. The northern line of the survey, commonly known as Hamilton’s Great Survey Line (or the 1751 grant line) which ran in a northeast to southwest direction, is still a visible landmark (National Park Service 1979:9).

Among the first to arrive were Dr. John Murray from Charleston, John Turk from Virginia, James Francis from Saludy Old Town, Andrew Williamson from Scotland, and John Lewis Gervais, a German immigrant. By the summer of 1751, Robert Gouedy had purchased 250 acres at Ninety Six just south of the Great Survey Line and had constructed a trading post along the Cherokee Path (also referred to as

The influx of settlers into the South Carolina high country caused the relations between the settlers and the Cherokees to deteriorate, finally breaking down in the spring of 1751 when a theft of 331 deerskins from a Cherokee hunting camp by white raiders went unpunished by the magistrate at Ninety Six (Cann 1974:7). By summer, retaliatory Indian raids became a constant threat, so two militia units were dispatched to patrol the high country. And, at the request of the local populace, the militia built a small military outpost on Gouedy’s property.

Following the deaths of several white settlers along the frontier, peace was restored for a brief period in 1753 when the British agreed to pay for the stolen deerskins and to help protect the Cherokee from their Indian enemies by building

The previous war, the War of Austrian Succession (known as King George’s War in the American colonies) had begun in 1740 and ended in 1748 with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which restored to

To counter the threat of additional Cherokee attacks, William Henry Lyttelton, who had succeeded Glen as Governor of South Carolina in 1757, promptly proceeded with reinforcements of over 1300 men to

The Cherokee War, 1760-1762

By the end of January 1760, the threat of Indian attack had prompted many settlers and their families to gather at Fort Ninety Six for safety. On February 2, a patrol from the fort took two Cherokee warriors prisoner, and the following day approximately 40 Cherokees attacked the fort, ultimately suffering 2 casualties and burning all the buildings on the Gouedy plantation except the successfully defended fort before withdrawing. The fort was besieged again briefly one month later when about 250 Cherokee attacked the fort at Gouedy’s on March 3. Under near-constant gunfire for roughly 36 hours, the garrison inside the fort suffered only two wounded, while the Cherokee reportedly suffered six dead. Before they withdrew, the Cherokee destroyed as much as they could within two miles of Ninety Six, setting fire to buildings, ruining grain supplies, and killing livestock (Cann 1974:11, 1996:5).

Asking for assistance in the war against the Cherokee, the provincial government’s requests were answered with the arrival of over 1300 British regulars under the command of Colonel Archibald Montgomery in

Grant and his troops arrived at Ninety Six in mid-May and made final preparations for his campaign against the Cherokee. History repeated itself with only one minor engagement occurring early in the campaign near Cowhowee, when the Cherokee ambushed the British and inflicted a loss of 19 dead and 52 wounded upon Grant’s army before fleeing the scene of the battle. For the remainder of the campaign, Grant met virtually no opposition as he marched his troops from one abandoned village to the next, burning the houses and fields as they went. Deprived of their homes and crops, the Cherokee soon capitulated and sued for peace. The Cherokee were required to return all prisoners and property seized during the war, to allow the British to build forts on their territory, and were prohibited from journeying below Keowee without permission.

The victorious Carolinians were also able to force additional land concessions from the defeated Cherokee, who surrendered to the English all lands south of a straight line drawn between the Reedy and Savannah Rivers, a line which today serves as the boundary between nearby Abbeville and Anderson Counties (The Historic Group 1981:72). Now open to white settlement, the

Although the end of the Cherokee War and the subsequent land concessions made

The remoteness and relatively low economic status of the majority of high country settlers also left most of the settlers in the Ninety Six area in the early 1770s feeling disenfranchised from the system of colonial government, whose control rested primarily in the hands of the wealthier low land bureaucrats. Unaffected by many of the economic and political concerns that confronted the low country inhabitants, such as the recent taxes levied on luxury goods (e.g., Townshend Duty Act of 1767 and Tea Act of 1773), the high country was far less receptive to the calls for independence from British rule that were now being circulated in Charleston and the colonies to the north. The dumping of tea into the harbor at

The

William Henry Drayton and the Reverend William Tennent were among those sent to the high country to enlist support against the Crown. Traveling the backcountry in the summer of 1775, they were met with strong opposition from the high country Loyalists. When their reports of Loyalist opposition reached the provisional government, they granted Drayton full authority to take the necessary measures for “eradicating the opposition” (Cann 1974:31). By early September, Drayton had followed the council’s orders by setting up headquarters at Ninety Six and assembled a militia of 225 patriots. Learning that opposing forces were gathering against him under the leadership of staunch Loyalist, Colonel Fletchall, commander of the

Aware that if war with

Meanwhile, the Loyalists, nearly 1900 men strong and deciding to take advantage of their recent acquisition of ample ammunition, struck out to attack Ninety Six under the command of Captain Patrick Cunningham. When Major Williamson learned of the impending assault, he ordered the hasty construction of a rude fort approximately 250 yards west of the Ninety Six jail that incorporated a barn and some outbuildings located on Colonel John Savage’s plantation. The Loyalists arrived before the makeshift fort could be completed and surrounded the badly outnumbered Patriots who consisted of 562 officers and men (Cann 1974:37).

The Loyalists demanded the Patriots surrender, but Williamson refused. But apparently neither side was keen on beginning hostilities, and half a day passed before shooting broke out when the Loyalists seized two of Williamson’s men after they wandered from the fort, presumably to get a drink from the nearby stream, Spring Branch. The exchange in fire had little effect on both sides, but the Patriots were cut off from access to water in the fort. To solve this problem, a well was dug inside the fort, reaching water at a depth of 40 feet. Two days later, hostilities were suspended after it was agreed the Patriots would be allowed to go free if they dismantled the fort, filled in the well, and handed over the swivel guns in their possession to the Loyalists. The Loyalists also agreed to return the swivel guns to the Patriot forces in three days time. Thus ended the first Revolutionary War engagement south of

War in the Backcountry, 1776-1781

The overwhelming defeat of the Loyalists forces by

The colonists immediately responded by setting their militias in motion. Colonel Andrew Williamson summoned the Ninety Six militia, and eventually collected 1,860 troops in a 17 day march to destroy the Lower Cherokee villages while General Griffith Rutherford and Colonel William Moore led the

Frustrated by their inability to deliver a crushing blow to rebel forces in the north, the British decided to evacuate

To repel any serious Patriot attacks in the south, the British established a string of forts from

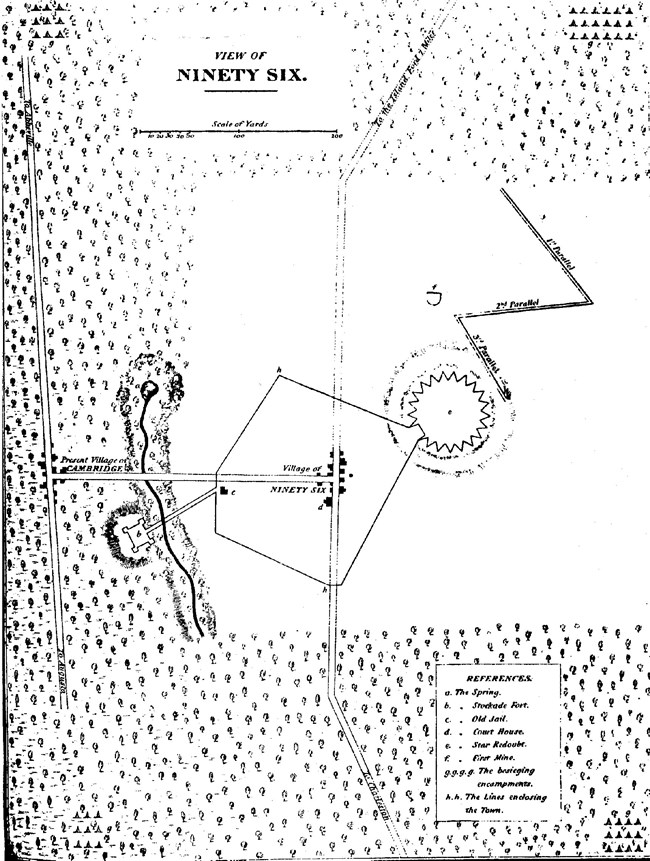

The construction of defensive works at Ninety Six were undertaken under the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel John Harris Cruger beginning in August of 1780. Later in December the same year, Lt. Henry Haldane, Aide de Camp to General Cormwallis, inspected the fortifications erected by Cruger and suggested several additions including an earthen fort in the shape of an eight-pointed star (Cann 1974:73-74). The defense works ultimately included a stockade with ditch around the village, two redoubts, a blockhouse, the star-shaped fort protected by a dry ditch and abatis, a hornwork (Holmes Fort) commanding the ravine west of the village, and a caponier that connected the hornwork to the town defenses. While he conducted his campaign in the South, Lord Cornwallis wrote repeatedly to his subordinate officers of the importance of holding Ninety Six.

Meanwhile, Cornwallis pressed his attacks northward into

Following the British successes in

His supplies exhausted, Cornwallis was unable to pursue the retreating American forces following the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, and was forced instead to withdraw to

The Siege of Ninety Six

After

With only 974 men at his disposal, Greene followed the advice of his military engineer, Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko, and concentrated his attack on the Star Fort (Image 5), the strongest point of the fortifications (Greene 1979:126-127). Initially, siege trenches to attack the fort were imprudently begun a mere 70 yards from the stronghold, but a barrage of cannon and musket fire followed by a Loyalist bayonet charge forced the Americans to abandon their trenches and begin again further back at a distance of some 200 yards. In support of the siege operations, Kosciuszko, directed the construction of two earthen cannon batteries approximately 350 yards north of the Star Redoubt “on the other side of a broad ravine” (Greene 1979:129). Slowed by the nearly rockhard soil, the first section or parallel of the siege trench was completed on May 27, and the second parallel on May 30. With only 70 yards to go to reach the Star Fort parapet, the construction of a third parallel was made more difficult by constant gunfire from the Star Fort. This impediment was soon silenced by the placing of snipers atop a log tower built near the third parallel. From their high vantage point, the American snipers pinned down the British defenders inside the Star Fort, immediately shooting anyone who attempted to raise their head above the parapet wall. With this advantage, Greene formally demanded the British surrender on June 3, but the commander of the fort, Lieutenant-Colonel John Cruger, having suffered few casualties was not disposed to accept.

To counter the vantage point provided by the tower, Cruger’s men added three feet to the Star Fort parapet using sandbags, leaving openings at intervals as portals for musket fire. Despite these measures, the sniper fire from the tower still made it perilous to man the cannon from the Star Fort, so they were dismounted and used only at night. Meanwhile, the Patriot forces continued to extend the siege trenches toward the Star Fort.

On June 8, Colonel Henry Lee arrived at Ninety Six from

While the Patriots patiently tunneled and dug closer to their respective objectives, the British responded by sending out sorties at night to destroy segments of the siegeworks and attack the guard parties located near the trenches. Despite these minor setbacks, the trenches were advanced to within a few feet of the Star Fort by June 12th, and Lee had succeeded in moving his cannon into a commanding position of Spring Branch from which the British got their water. With access cut off to their only water source, the British defenders attempted to dig a well within the Star Fort, but failed to reach water.

While Greene waited patiently for the siege trenches and the tunnel to reach their objectives, news of the siege of Ninety Six had reached

After Greene’s retreat, the British reasoned that keeping the isolated outpost garrisoned would be too difficult, and decided instead to evacuate Ninety Six. The fortifications were dismantled and the town was destroyed. The British then withdrew from the backcountry, back to

With Ninety Six destroyed, those returning to resettle the area following the Revolutionary War, decided to reestablish the former community in a different location. In August 1783, the new town was laid out near the former location of Holmes Fort on 180 acres that had been among the 400 acres confiscated by the South Carolina General Assembly from Loyalist James Holmes (Caldwell 1974:1). The land was vested to seven trustees who were responsible for laying out the town and establishing a public school.

Those who had held lots in Ninety Six prior to the war were given the opportunity to exchange their lots for ones in the new town, which was renamed Cambridge in 1787 (Holschlag and Rodeffer 1976b:4). The

In addition to the

Cambridge’s downfall began less than a decade after its founding, when the size of the Ninety Six Judicial District was reduced in 1791 and abolished altogether in 1800 (Baker 1972:42; Holschlag and Rodeffer 1977:12; Greene 1979:180). After the loss of the six county judicial district seat, merchants began to leave as well. By 1803, low attendance forced the trustees of the

REFERENCES

Alvord, Clarence W., and Lee Bidgood.

1912 First Explorations of the Trans-Allegheny Region by the Virginians, 1650-1674. Arthur H. Clark Co., Cleveland.

Anderson, David G.

1975 Inferences from Distributional Studies of Prehistoric Artifacts in the Coastal Plain of South Carolina. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 18:180-194.

1985 Middle Woodland Societies on the Lower South Atlantic Slope: A View from Georgia and South Carolina. Early Georgia 13 (1-2):29-66.

1989 The Mississippian in South Carolina. In Studies in South Carolina Archaeology: Papers in Honor of Robert L. Stephenson, edited by Albert C. Goodyear III and Glen T. Hanson, pp. 101-132. Anthroplogical Studies No. 9, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

1990a The Paleoindian Colonization of Eastern North America: A View From the Southeastern United States. In Research in Economic Anthropology, ed. by Kenneth B. Tankersley and Barry L Isaac. Supplement 5, pp. 163-216, JAI Press, Inc., Connecticut.

1990b Stability and Change in Chiefdom-Level Societies: An Examination of Mississippian Political Evolution on the South Atlantic Slope. In Lamar Archaeology: Mississippian Chiefdoms in the Deep South., edited by Mark Williams and Gary Shapiro, pp. 187-213. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

1994 The Savannah River Chiefdoms: Political Change in the Late Prehistoric Southeast. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

1996 Models of Paleoindian and Early Archaic Settlement in the Lower Southeast. In The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman, pp. 29-57. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Anderson, David G. (editor)

1996 Indian Pottery of the Carolinas: Observations from the March 1995 Ceramic Workshop at Hobcaw Barony. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

Anderson, David G., and Glen T. Hanson

1988 Early Archaic Settlement in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study from the Savannah River Valley. American Antiquity 53(2): 262-286.

Anderson, David G., and J. W. Joseph

1988 Prehistory and History Along the Upper Savannah River: Technical Synthesis of Cultural Resource Investigations, Richard B. Russell Multiple Resource Area. National Park Service, Interagency Archeological Services, Atlanta.

Anderson, David G., S. T. Lee, and A. R. Parler

1979 Cal Smoak: Archaeological Investigations along the Edisto River in the Coastal Plain of South Carolina. Occasional Papers 1. Archaeological Society of South Carolina, Columbia.

Anderson, David G., and Kenneth E. Sassaman

1996 Paleoindian and Early Archaic Research in the South Carolina Area. In The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman, pp. 222-237. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Anderson, Elaine

1984 Who's Who in the Pleistocene: A Mammalian Bestiary. In Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution, edited by Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein, pp. 40-89. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Aubry, Michele C., Dana C. Linck, Mark J. Lynott, Robert R. Mierendorf, and Kenneth M. Schoenberg

1992 National Park Service's Systemwide ArcheologicalInventory Program. National Park Service, Anthropology Division, Washington, D.C.

Baker, Steven G.

1972a A House on Cambridge Hill (38-GN-2); An Excavation Report. Research Manuscript Series #27, Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

1972b Colono-Indian Pottery from Cambridge, South Carolina with Comments on the Historic Catawba Pottery Trade. The Notebook 4(1):3-30. Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Benson, Donna L.

1983 A Taxonomy for Square Cut Nails. The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers 15:123-152.

Benson, Robert W.

1995 Survey of Selected Timber Stands in Enoree Ranger District Sumter National Forest Laurens and Newberry Counties South Carolina. Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests Cultural Resource Management Report #95-12. Southeastern Archeological Services, Athens, Georgia.

Blanton, Dennis B., and Kenneth E. Sassaman

1989 Pattern and Process in the Middle Archaic Period of South Carolina. In Studies in South Carolina Archaeology: Papers in Honor of Robert L. Stephenson, edited by Albert C. Goodyear III and Glen T. Hanson, pp. 53-72. Anthroplogical Studies No. 9, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Braun, Emma L.

1950 The Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. Hafner Publishing Co., New York.

Brewer, David

2000 Fort Caroline National Memorial Archeological Survey and Testing 1996 and 1997 Field Seasons. National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee.

Bushnell, Amy T.

1994 Situado and Sabana: Spain's Support System for the Presidio and Mission Provinces of Florida. Anthropological Papers No. 74, American Museum of natural History, New York.

Cable, John S., and James L. Michie

1977 Subsurface Tests of 38-GR-30 and 38-GR-66, Two Sites on the Reedy River, Greenville County, South Carolina. Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Research Manuscript Series 120.

Caldwell, Joseph R.

1958 Trend and Tradition in the Prehistory of the Eastern United States. Memoir 88, American Anthropological Association, Menasha, Wisconsin

Caldwell, Joseph R., and Antonio J. Waring, Jr.

1968 Some Chatham County Pottery Types and Their Sequence. In The Waring Papers: The Collected Works of Antonio J. Waring, Jr., edited by Stephen J. Williams, pp. 110-133. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology 58, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Caldwell, DeLane M.

1974 Cambridge, South Carolina, 1783 - 1850. Manuscript on file, National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida.

Cann, Marvin L.

1974 Ninety Six¾A History of the Backcountry 1700-1781. Department of History, Lander College, Greenwood, South Carolina.

1996 Ninety Six, A Historical Guide: Old Ninety Six in the South Carolina Backcountry 1700-1781. Sleepy Creek Publishing, Troy, South Carolina.

Cann, Marvin L., Michael J. Rodeffer and Louise M. Watson

1974 Master Plan of Development. Ninety Six National Historic Site, South Carolina.

Chapman, Ashley A., II

2000 An Archaeological Survey of Selected Timber Compartments in the Sumter National Forest, South Carolina. Technical Report 700, New South Associates, Stone Mountain, Georgia.

Chapman, Jefferson

1985 Archaeology and the Archaic Period in the Southern Ridge-and-Valley Province In Structure and Process in Southeastern Archaeology, edited by Roy S. Dickens and H. Trawick Ward, pp. 137-153. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Chapman, Jefferson, and Bennie C. Keel

1979 Candy Creek-Connestee Components in Eastern Tennessee and Western North Carolina and Their Relationship with Adena-Hopewell. In Hopewell Archaeology: The Chillicothe Conference., edited by David S. Brose and N'omi Greber, pp 157-161. Kent State University Press, Kent.

Chapman, Jefferson, and Andrea B. Shea

1981 The Archaeobotanical Record: Early Archaic Period to Contact in the Lower Little Tennessee River Valley. Tennessee Anthropologist 6:61-84.

Chevis, Langdon

1897 The Shaftsbury Papers and Other Records Relating to Carolina and the First Settlement on Ashley River Prior to the Year 1676. Collection of the South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston.

Coe, Joffre L.

1964 The Formative Cultures of the Carolina Piedmont. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 54, part 5, Philadelphia.

Cook, James

1773 A Map Of The Province Of South Carolina With All The River, Creeks, Bays, Inletts, Islands, Inland Navigation, Soundings, Time Of High Water On The Sea Coast, Roads, Marshes, Ferrys, Bridges, Swamps, Parishes, Churches, Towns, Townships; County Parish District And Province Lines. Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Cornelison, John

1996 Trip Report for Archeological Testing at Ninety Six National Historic Site (NISI) Prior to the Construction of a Septic Tank and Two Drainage Lines, September 7, 1995, SEAC Acc. 1192. Trip report on file, National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee.

Craddock, G.R., and C.M. Ellebe

1966 General Soil Map of Greenwood County. Extension Service, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina.

Crane, Vernon W.

1929 The Southern Frontier 1670-1732. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Crites, Gary D.

1991 Investigations into Early Plant Domestication and Food Production in Middle Tennessee: A Status Report. Tennessee Anthropologist 16:69-87.

Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr. (editor)

1990 The Travels of James Needham and Gabriel Arthur Through Virginia, North Carolina, and Beyond, 1673-1674. Southern Indian Studies 39:31-55.

Delcourt, Paul A., and Hazel R. Delcourt

1981 Vegetation Maps for Eastern North America: 40,000 Yr. B.P. to the Present. In Geobotany II, edited by Robert C. Romans, pp. 123-166. Plenum Press, New York.

DePratter, Chester B.

1989 Cofitachequi: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Evidence. In Studies in South Carolina Archaeology: Papers in Honor of Robert L. Stephenson, edited by Albert C. Goodyear III and Glen T. Hanson, pp. 133-156. Anthroplogical Studies No. 9, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

DePratter, Chester B., and Christopher Judge

1990 Wateree River. In Lamar Archaeology: Mississippian Chiefdoms in the Deep South., edited by Mark Williams and Gary Shairo, pp. 56-58. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

DePratter, Chester B., Stanley South, and James Legg

1996 The Discovery of Charlesfort. Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina 101:39-48.

Deagan, Kathleen, and Darcie MacMahon

1995 Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Dickens, Roy S.

1976 Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Eastman, Jane M.

1994 The North Carolina Radiocarbon Date Study. Southern Indian Studies 43.

Ehrenhard, Ellen B.

1978 The Utilization of Inorganic Phosphate Analysis for the location of General Nathanael Greene's Revolutionary War Camp. National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida.

1979a Cambridge 38-GN-2 Ninety Six National Historic Site, South Carolina, Waterline Investigation. National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida.

1979b Cultural Resource Inventory Ninety Six National Historic Site. National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida.

Ehrenhard Ellen B., and W. H. Wills

1980 Ninety Six National Historic Site South Carolina. In Cultural Resources Remote Sensing, edited by Thomas R. Lyons and Frances Joan Mathien, pp. 229-291. U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C.

Elliot, Daniel T.

1987 Archaeological Testing on 38FA188, Fairfield County, South Carolina. Prepared for Law Environmental, Inc. by Garrow and Associates, Inc., Atlanta.

Fenneman, Nevin M.

1930 Physical Divisions of the United States. 1:7,000,000 scale map, U.S. Geological Survey.

1938 Physiography of the Eastern United States. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Ferris, Robert G. (editor)

1968 Explorers and Settlers: Historical Places Commemorating the Early Exploration and Settlement of the United States. National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

Fontana, Bernard L., and J. Cameron Greenleaf

1962 Johnny Ward's Ranch: A Study in Historic Archaeology. The Kiva 28:1-115.

Fowler, Melvin L.

1959 Modock Rockshelter: An Early Archaic Site in Southern Illinois. American Antiquity 24:257-270.

Ferguson, Leland G.

1971 South Appalachian Mississippian. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Goodyear, Albert C., III

1982 The Chronological Position of the Dalton Horizon in the Southeastern United States. American Antiquity 47:382-395.

Goodyear, Albert C., III, J.H. House, and N.W. Ackerly

1979 Laurens-Anderson: An Archaeological Study of the Inter-Riverine Piedmont. Anthropological Studies 4. Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Goodyear, Albert C., III, James L. Michie, and Tommy Charles

1989 The Earliest South Carolinians. In Studies in South Carolina Archaeology: Papers in Honor of Robert L. Stephenson, edited by Albert C. Goodyear III and Glen T. Hanson, pp. 19-52. Anthroplogical Studies No. 9, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Greene, Jerome

1979 Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report Ninety Six: A Historical Narrative. National Park Service, Denver Service Center, Denver, Colorado.

Gremillion, Kristen J.

1993 Plant Husbandry at the Archaic/Woodland Transition: Evidence from Cold Oak Shelter, Kentucky. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 18(2):161-189.

Griffin, James B.

1967 Eastern North American Archaeology: A Summary. Science 156: 175-191.

1985 Changing Concepts of the Prehistoric Mississippian Cultures of the Eastern United States. In Alabama and the Borderlands; From Prehistory to Statehood, edited by R. Reid Badger and Lawrence A. Clayton, pp. 40-63, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

de Grummond, Elizabeth, and Christine Hamlin

2000 Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Archeological Overview and Assessment. National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center, Tallahassee.

Hanson, Glenn T., and Chester B. DePratter

1985 The Early and Middle Woodland Period in the Savannah River Valley. Paper presented at the 42nd Southeaster Archaeological Conference, Birmingham.

Hanson, Glenn T., R. Most, and David G. Anderson

1978 The Preliminary Archaeological Inventory of the Savannah River Plant, Aiken and Barnwell Counties, South Carolina. Research Manuscript Series 134. Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Hann, John

1988 Apalachee: The Land Between the Rivers. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Herbert, Joseph M. and Mark A. Mathis

1996 An Appraisal and Re-Evaluation of the Prehistoric Pottery Sequence of Southern Coastal North Carolina. In Indian Pottery of the Carolinas: Observations from the March 1995 Ceramic Workshop at Hobcaw Barony, edited by David G. Anderson, pp. 136-189. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

Hilton, William

1664 A True Relation Of A Voyage Upon Discovery Of Part Of The Coast Of Florida. Reproduced by the South Carolina Historical Society, Collections 5:18-28.

Historic Group, The