______________________________

Moores Creek National Battlefield Park

CULTURAL OVERVIEW

By Lou Groh (1998)

______________________________

NATIVE AMERICAN ARCHEOLOGY AND CULTURE HISTORY

Unfortunately, little attention has been paid to the history of Precolumbian Native American cultures in the park and in the immediate surrounding area. As a result, cultural chronologies based on archeological work conducted in adjacent areas have been extended to provide an interim framework for those past Native American cultures expected to occur within the local area. The chronological framework employed here has been largely adopted from information obtained from Phelps (1983), Anderson et al. (1996), and Trinkley et al. (1996).

PALEOINDIAN (10,500 - 8000 B.C.)

The earliest known human inhabitants in the New World are referred to as the Paleoindians. They are believed to have migrated across the Bering Strait land bridge to North America during the last glacial age. Archeological evidence confirms Paleoindian occupation in the southeastern United States between 10,500 and 8000 B.C. Current interpretations of the archeological record portray Paleoindian peoples as nomadic, egalitarian bands composed of several nuclear or extended families (Anderson 1990; Morse and Morse 1983). The Paleoindian period climate and environment were in transition and consid-erably different than at present, with sea levels seventy or more meters lower than they are today (Anderson et al. 1996:4). The available global water was taken up by massive polar ice sheets, which exposed much of what is now the North American continental shelf in the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Coastal shorelines were frequented by the Paleoindians, and this is evidenced by submerged sites found on the continental shelf today (Dunbar and Webb 1996:351-354).

With the generally colder temperatures of the time period, the Southeast was a scene of vastly different floral and faunal communities, including now extinct Pleistocene megafauna such as mastodons and giant ground sloths.

Until relatively recently, the amount of contact between megafauna and Paleoindian hunters was hotly debated. However, the discoveries of a speared giant tortoise from Little Salt Springs (Clausen et al. 1979) and the skull of a Bison antiquus with a projectile point embedded in its forehead from the Wacissa River (Webb et al. 1984) provide direct association of Pleistocene fauna and Paleoindians in the lower Southeast (Anderson et al. 1996:3).

Whether Paleoindian hunters only contributed to or actually caused the extinction of North America's megafauna is still a matter of debate. Changing environmental factors also appear to have played a role in their demise. Controversy also exists concerning the role of megafauna in the subsistence strategy of Paleoindian populations. Although it is commonly assumed that Paleoindians were big-game hunting specialists, there is actually little direct evidence to support this generally accepted theory.

As the last glacial age came to a close, the Southeast experienced rapid environmental change. The sea levels rose to within a few meters of present levels, and the patchy boreal forest that covered much of the landscape was eventually transformed to mesic oak-hickory forest. "The best evidence suggests this transition was complete over much of the lower Southeast by shortly after 10,000 B.P. [8000 B.C.], and almost certainly by 9000 B.P. [7000 B.C.]"(Anderson et al. 1996:4).

The Paleoindians of the North Carolina Coastal Plain are poorly represented in the archeological record, as fewer than fifty Paleoindian sites in this area have been recorded (Phelps 1983:18). Recently, it has been suggested that few Paleoindian sites should be expected in the lower southeastern Coastal Plain (except in Florida where environmental conditions differed considerably) "since the initial founding populations were apparently not technologically and organizationally adapted to such an environment" until late in the Paleoindian period (Anderson et al. 1996:7).

The Paleoindian period has been subdivided into three sequential temporal groupings: Early, Middle, and Late Paleoindian (Anderson 1990; O'Steen et al. 1986:9). These correspond with changes in lithic technology and, presumably, changes in subsistence patterns and other lifeways.

Early Paleoindian (10,500 - 9000 B.C.)

Clovis projectile points are temporally diagnostic artifacts from the Early Paleoindian period. Sellards (1952) and Wormington (1957) describe the points as being relatively large lanceolate forms with nearly parallel sides, ground haft margins, slightly concave bases, and single or multiple flutes that rarely extend more than a third of the way up the body (Anderson et al. 1996:9). Often points that resemble the classic Clovis are also attributed to the Early Paleoindian period. Other names sometimes used to describe these forms are Eastern Clovis and Gainey (Anderson et al. 1996:9; MacDonald 1983; Mason 1962; Shott 1986; Simons et al. 1984).

Middle Paleoindian (9000 - 8500 B.C.)

The Middle Paleoindian period is characterized by smaller fluted points, unfluted lanceolate points, and fluted or unfluted points with broad blades and constricted haft elements. Common Southeastern forms include Suwannee, Simpson, Clovis Variant, and Cumberland types (Anderson et al. 1996:11). The Clovis Variant (Anderson et al. 1992; Michie 1977:62-65) are smaller fluted forms, some of which appear to be extensively resharpened Clovis points. Clovis Variant points occur mostly in the South Appalachian Piedmont (Anderson et al. 1996:11). Cumberland types are the most common types recovered in the mid-South. They are characterized by Lewis (1954) as being narrow, deeply fluted, slightly waisted lanceolates with faint ears and a slightly concave base (Anderson et al. 1996:11). Beaver Lake and Quad types are sometimes assigned to the Late or transitional Middle/Late Paleoindian period (Anderson et al.1996:12)

Late Paleoindian (8500 - 8000 B.C.)

Hardaway-Dalton projectile points are assigned to the Late Paleoindian period. Related point styles including Quad, San Patrice, and Beaver Lake types (Anderson et al. 1996:12; Coe 1964; Goodyear 1974, 1982:390; Justice 1987:35-44; Morse 1971a, 1971b, 1973; Webb et al. 1971). Dalton-Hardaway points are described as having a lanceolate blade outline and a concave base that is sometimes thinned and ground on the lateral and basal margins. The edges of the blade may be incurvate, straight, or excurvate and are frequently serrated (Cambron and Hulse 1975; DeJarnette et al. 1962:47, 84; Justice 1987:35-36). Beaver Lake points are characterized as small, slightly waisted lanceolates with very faint ears, a weakly concave base, and moderate basal thinning (Cambron and Hulse 1975; DeJarnette et al. 1962:47, 84; Justice 1987:35-36). Quad points are small lanceolates with distinct ears, concave bases, and pronounced basal thinning, sometimes to the point of appearing fluted (Anderson et al. 1996:12; Cambron and Hulse 1975; DeJarnette et al. 1962:47, 84; Justice 1987:35-36; Soday 1954:9).

Another sequence for the Paleoindian period of the Piedmont area (Oliver 1981a:16, 1985:199-200) recognizes four developmental phases of projectile points as follows: (1) the Hardaway Blade, considered a regional variant of the Clovis, which evolves into (2) the Hardaway-Dalton semi-lanceolate, which in turn evolves into (3) the Hardaway Side Notched, and in turn gives rise to (4) the Palmer Corner Notched. Phelps (1983:19) acknowledges that the final phase, Palmer Corner Notched, is often defined as Early Archaic rather than Late Paleoindian period, and personally defines the type as transitional. Trinkley discusses Oliver's typology in the following paragraph.

Oliver (1981b, 1985) has proposed to extend the Paleoindian dating in the North Carolina Piedmont to perhaps as early as 14,000 B.P. [12,000 B.C.], incorporating the Hardaway Side-Notched and Palmer Corner-Notched types, usually accepted as Early Archaic, as representatives of the terminal phase. This view, verbally suggested by Coe for a number of years, has considerable technological appeal. Oliver suggests a continuity from the Hardaway Blade through the Hardaway-Dalton to the Hardaway Side-Notched, eventually to the Palmer Side-Notched [Oliver 1985:199-200]. While convincingly argued, this approach is not universally accepted. [Trinkley et al. 1996:25]

ARCHAIC (8000 - 1000 B.C.)

Archaic cultures in the Southeast are recognized as very successful adaptations to the new forest communities and related animal populations that followed the end of the last ice age. Like the preceding Paleoindian period, the Archaic period has been typically divided by Southeastern archeologists into three subdivisions: Early, Middle, and Late Archaic.

Early Archaic (8000 - 6000 B.C.)

The temporally diagnostic artifact assemblage of Early Archaic culture (8000-6000 B.C.) on the North Carolina Coastal Plain includes the following projectile points: Palmer, a corner-notched point that is considered by some to be transitional from Late Paleoindian to Early Archaic; Kirk Corner Notched, which is generally attributed solely to the Early Archaic period; and Kirk Stemmed, which gradually replaces the Kirk Corner Notched and often exhibits a serrated blade. Toward the end of the Early Archaic, bifurcate stemmed points, such as LeCroy and Kanawha (Justice 1987:85-96) are also sporadically found. The Early Archaic tool kit also includes end- and sidescrapers, blades, and drills that exhibit manufacturing techniques similar to those used during the Paleoindian period.

Middle Archaic (6000 - 3000 B.C.)

The Middle Archaic period coincides with a period of warmer and drier climate referred to as the Hypsithermal Interval (Delcourt and Delcourt 1981:150). During this period, the oak and hickory forests that had come to dominate the Atlantic Coastal Plain following the last ice age were replaced by southern pine forest. Since the close of the Hypsithermal (3000 B.C.), southern pine has remained the dominant forest type of the North Carolina Coastal Plain except for the cypress-gum forests inhabiting the Green Swamp just west of Cape Fear and the Dismal Swamp regions of Albemarle Sound.

Changes in the tool assemblages used by Middle Archaic peoples accompanied the changes in climate and forest communities. The new artifact assemblage included Stanly Stemmed (ca. 6000-5000 B.C.) projectile points, polished stone artifacts, and semilunar spearthrower weights. Other new point types, including Morrow Mountain (ca. 5500-3500 B.C.) and Guilford (ca. 4500-3500 B.C.), are thought to have been introduced into North Carolina from western Piedmont sources (Coe 1964:123; Phelps 1983:23).

Late Archaic (3000 - 1000 B.C.)

The Late Archaic (3000-1000 B.C.) was a period of major technological and economic change for North Carolina's native peoples. With increasing population levels and concomitantly shrinking territories, native populations experienced reduced residential mobility, but still continued their seasonal movements in order to exploit natural resources as these became seasonally available. Perhaps as a compensation for reduced territorial size, Late Archaic peoples participated in long-distance exchange networks to obtain nonlocal resources. And, although evidence is currently lacking, it is possible that Late Archaic peoples along the North Carolina Coastal Plain were experimenting with plant husbandry-a change in subsistence practices that other Late Archaic groups in the Southeast are now known to have adopted.

Projectile point styles also continued to change, although the exact time range of certain types remains somewhat ambiguous. Large Savannah River Stemmed points, which began to appear near the close of the Middle Archaic, were probably made throughout the Late Archaic and were predominant in the Middle and South Atlantic Coastal Plain (House and Ballenger 1976:24). Other innovations of the period included the manufacture and use of steatite (soapstone) vessels for cooking and perforated soapstone disks that were apparently used in the stone-boiling cooking method. By the end of the period (1000 B.C.), Late Archaic groups over much of the state had, to some extent, adopted the manufacture and use of pottery.

WOODLAND PERIOD OF THE SOUTH COASTAL REGION (1000 B.C. - CONTACT)

The temporal division drawn between the Archaic period and the succeeding Woodland period on the Coastal Plain is somewhat blurred and a point of continuing discussion among members of the archeological community. It is debated because the introduction and use of pottery, a primary trait for assigning Woodland cultural affiliation, developed rapidly in some areas of the Southeast but was slow to advance in others. Determining the temporal division is additionally complicated in the Moores Creek area because Moores Creek lies near the fluctuating boundary between two distinct cultural traditions, which later witnessed the development of relatively independent ceramic traditions (Herbert and Mathis 1996:141-142; Phelps 1983:27). It is further complicated by the lack of well-documented and well-dated ceramic assemblages (Anderson, ed. 1996).

The initial introduction of pottery is viewed by many archeologists as an inappropriate time marker for distinguishing Archaic from Woodland cultures in the Georgia-Carolina region because pottery was not widely used during the first millennium, or more, after its introduction around 2500 B.C. People living on the Georgia-Carolina coast, along with those living in the Savannah River Valley, peninsular Florida, and small portions of the mid-South, developed early pottery traditions that were not matched in surrounding and intervening areas. As Sassaman and Anderson explain:

Pottery seems to have been grafted onto an existing Late Archaic technology with little change in settlement and subsistence…. What is more, the development of pots for use over fire was a slow and uneven process, with coastal populations quick to adopt innovations and riverine populations lag-ging behind for reasons that may have little to do with pottery function or efficiency....It was not until about 3,000 B.P. [1000 B.C.] that pottery was widely employed across the Southeast....Given these developments, 3,000 B.P. [1000 B.C.] represents a meaningful turning point in Southeastern prehistory, and a rational place to draw the temporal line between Archaic and Woodland periods. [1995:30]

Toward the end of the Late Archaic period, approximately 2000 B.C. (Phelps 1983:26), the region encompassing the Cape Fear River drainage saw the first introduction of pottery-the Stallings Island fiber-tempered series (Sears and Griffin 1950). However, of the thirty-eight sites with Stallings Island pottery that were studied by Phelps (1983) in the North Carolina south coastal region, the only type represented in the collections is Stallings Island Plain (Sears and Griffin 1950). This implies that the full-fledged ceramic series with its decorative types did not extended into the south coastal region of North Carolina (Phelps 1983:26). Phelps describes the limited distribution of fiber-tempered pottery in North Carolina at the end of the Late Archaic and the distinct ceramic traditions that evolved between the north coastal and south coastal regions of North Carolina following its introduction.

Sites with Stallings Plain sherds are concentrated from the Neuse River system southward….It appears that the distribution of fiber-tempered pottery north of the Neuse river is rare, representing a minor influx….In succeeding centuries the boundary moved southward, but the two regions it defined within the North Carolina Coastal Plain remained distinct and by about 1000 B.C. had developed their own characteristic traits. [Phelps 1983:26-27]

Sand-tempered Thom's Creek pottery was also added to the ceramic assemblage near the end of the Late Archaic period. In the currently accepted ceramic cultural sequence for the Cape Fear River area (Phelps 1968; Trinkley et al. 1996), Stallings Island fiber-tempered ware precedes, is later contemporaneous with, and, around 1500 b.c., is eventually replaced by Thom's Creek sand-tempered pottery as the result of the introduction of new technological traits in ceramic production. Thom's Creek, in turn, is followed by the coarse sand-tempered New River series, which dates roughly to between 1000 and 300 B.C. (Herbert and Mathis 1996; Trinkley et al. 1996). Toward the later half of the Early Woodland period, minor numbers of Deptford series ceramics appear and signal the immanent arrival of Middle Woodland cultures in the area.

The introduction of coarse sand and grit (rock) tempered pottery types, such as New River and Deep Creek, is a defining hallmark of Early Woodland culture in the North Carolina Coastal Plain. Small, stemmed, triangular bladed projectile points, such as the Gypsy and Roanoke points, are also typical of the Early Woodland culture in this area.

Somewhat different ceramic sequences occur within the Coastal Plain immediately to the south (Anderson et al. 1982; Ledbetter 1995; Steen and Braley 1994). The existence of this ceramic sequence is considered the result of a "ripple effect" in the area of the Pee Dee River drainage in South Carolina. This probably represents the most northerly extent of the complete Stallings Island ceramic series, with Stallings Island Plain rarely found north of the Neuse River. Thom's Creek ware appears to reach its northernmost extent at the Neuse River, and Refuge (ca. 1000-500 B.C.) and Deptford (ca. 600 B.C.-A.D. 500) types are only rarely found north of the Cape Fear River (Anderson, ed. 1996; Herbert and Mathis 1996; Lilly and Gunn 1996; South 1976; Wilde-Ramsing 1978).

Early Woodland (1000 - 200 B.C.)

The dominant Early Woodland period pottery type for the south coastal region is a coarse sand-tempered ware that Loftfield (1976:149-154) terms New River. The attributes of New River pottery closely resemble the Deep Creek pottery types identified by Phelps (1983:29-31) for the north coastal area of North Carolina, and have been subsumed in Phelps's (1983:31) Deep Creek typology in his attempt to standardize the Coastal Plain ceramic chronology. This unification of types has apparently not attracted much support, however, with Loftfield's New River series still being used in the archeological literature (e.g., Herbert and Mathis 1996:145; Trinkley et al. 1996:32) when referring to the south coastal region.

Essentially identical to Deep Creek pottery, New River pottery is tempered with coarse sand. New River pottery may be "thong marked" (i.e., simple stamped), cord marked, net impressed, fabric impressed, and plain (often smoothed). Although there are few radiocarbon dated assemblages for either Deep Creek or New River (Herbert and Mathis 1996:140-145), both are assumed to be roughly contemporaneous.

Three phases have been suggested for the Deep Creek series tentatively dated from roughly 1000 to 200 B.C. Deep Creek I (ca. 1000-800 B.C.) is characterized by coarse sand-tempered wares dominated by cordmarking with some simple stamping and the first evidence of net/fabric impressing. Phelps is of the opinion that "the origin of this simple stamping lies somewhere within the Stallings Island-Thom's Creek continuum but is reinforced by the paddle-stamped type that is typical of the later Deptford phase" (1983:30-31). Deep Creek II (800-500 B.C.?) has an increased emphasis on simple stamping and net- and fabric-impressed surface treatments (Herbert and Mathis 1996:144). Concomitantly, there is a decrease in the use of cordmarking on vessel exteriors. Deep Creek III (500-200 B.C.) is characterized by decreasing popularity in the use of simple stamping with a continuance of cord-, net-, and fabric-impressed decorative motifs.

Although New River and Deep Creek pottery decorative techniques are virtually identical, the occurrence of net- and fabric-impressed surface treatments is more prevalent in the coastal area north of the Neuse River.

Not enough data is available to speak definitively about the subsistence and settlement patterns exhibited by the Early Woodland peoples in the North Carolina Coastal Plain. Settlement patterns similar to the Late Archaic have been suggested (Phelps 1976), with base campsites being located in riverine settings where major streams are accessible. However, this hypothesis is based primarily on surface collected materials (Phelps 1983:32). Sassaman and Anderson (1995:151) suggest that applying Milanich's (1971, 1972) transhumance model of seasonal movements between the coast and the interior lower Coastal Plain produces anomalous data. Widmer's (1976) model, on the other hand, depicts two discrete adaptive systems-one on the coast and the other in the interior. According to this model, the coastal adaptation was sedentary whereas the interior groups were semi-nomadic, moving up and down rivers in a seasonal manner (Sassaman and Anderson 1995:151).

Middle Woodland (200 B.C. - A.D. 800)

The Middle Woodland period, typically dated from 200 B.C. to A.D. 800, is more clearly understood than the Early Woodland period because more information is available. Trinkley and his associates (1996) suggest that the best data currently available is represented by Phelps's (1983) Mount Pleasant series developed for the north coastal region. However, for the south coastal region, medium-sized sand-tempered Cape Fear and grog-tempered Hanover ceramics are considered hallmarks of the Middle Woodland period (Herbert and Mathis 1996:147).

The Mount Pleasant phase ceramic complex appears to be a traditional continuity from the earlier Deep Creek ware, varying from the latter in a possibly higher frequency of net-impressed surface finish, a trend toward larger clastic temper, and the addition of incised decoration. The size of the tempering material varies widely, a fact noted by Haag (1958:71) in the analysis of his "Middle Period" grit-tempered ware (Phelps 1983:33).

South (1976:18) originally defined Middle Woodland south coastal region ceramics as the Cape Fear and Hanover series. Phelps (1983), however, subsumes the Cape Fear pottery into his north coastal Mount Pleasant series. Similarly, Loftfield (1976) has subsumed South's Hanover series within his Carteret series. Loftfield (1976) also offers a type description for a poorly understood Onslow series-a crushed quartz-tempered ware with cord-marked and fabric-impressed surfaces-which he places between Carteret and White Oak (a Late Woodland phase).

Trinkley and his co-writers (1996) admit that very little is known about the people who produced the Cape Fear and Hanover ceramics found by South (1976) in the south coastal region, but they can describe the various attributes of these people's pottery. Cape Fear pottery is sand-tempered, the sand particles being of medium size (0.25-0.50 mm) using the Wentworth scale (Herbert and Mathis 1996). Surface decorations include cord marked, fabric marked, net impressed, and plain. Hanover pottery is distin-guished on the basis of clay- and sherd-tempering with some suggestion that the majority of the temper is composed of crushed sherds. Hanover wares surface decorations include fabric impressed, cord marked, and plain.

The presence of small, low, sand burial mounds during the Cape Fear phase is a unique trait of the Middle Woodland period in the south coastal region. The geographical boundaries of these mounds appear to be confined from the Cape Fear River drainage northward to the Neuse River. The contents of the mounds include secondary cremations and platform pipes, many of which are similar to those recovered from mounds of the Middle Woodland period from other regions of the Southeast. Phelps dis-cusses Brose and Greber's (1979) suggestion that the similarities in the contents of mounds and their placement away from the habitation areas may have resulted from contact with other groups participating in the Hopewell Interaction Sphere (Phelps 1983:35).

Late Woodland (A.D. 800 - Contact)

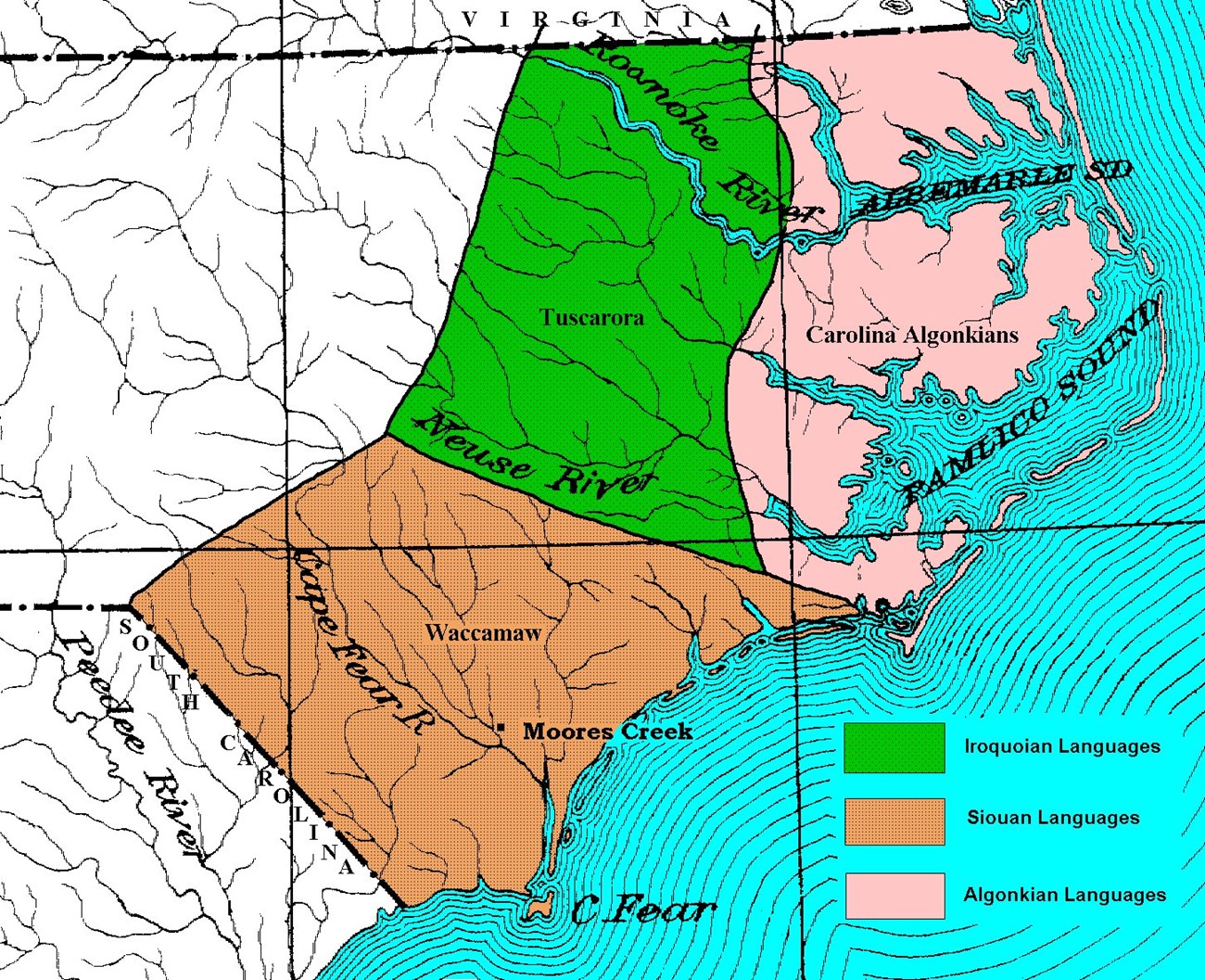

Archeological and related ethnohistorical research of the Carolina Coastal Plain has shown that the area was occupied by peoples of several language groups during the Late Woodland period. The Carolina Algonkians occupied the coast from north of the Virginia border to roughly south of the Neuse River. Tuscarora speakers occupied the inland area to the west. Siouan language groups (including the Cape Fear and Waccamaw) inhabited the south coastal region south of the Neuse River and east of the fall line (Image 1).

South (1976:5-8) has voiced the opinion that the shell-tempered Oak Island ceramic series is a Siouan cultural indicator for the Late Woodland period in the south coast region based on summarized ethnographic documents and archeological evidence. Oak Island decorative attributes include cord-marked and net- or fabric-impressed surface decorations. South's Oak Island series is virtually the same as Loftfield's (1976) shell-tempered White Oak series, a fact that led Phelps (1983:48) to suggest that White Oak be subsumed under Oak Island and, likewise, has led to the classification of the region's Late Woodland shell-tempered ceramics by some archeologists as "Oak Island/White Oak" (Herbert and Mathis 1996:151).

Other artifacts typically associated with the Late Woodland period include small varieties of triangular points, shell beads, bone pins, bone fishhooks, small polished stone celts, copper adornments, and pipes. Perhaps the best evidence associating the Oak Island wares with a specific ethnic group is the research conducted at a New Hanover County ossuary where the skeletal population was identified as having Siouan physical traits (Coe et al. 1982).

The association of Oak Island wares with Late Woodland peoples has been muddied somewhat by the recent realization that some of the pottery previously identified as shell tempered Oak Island is actually limestone- and marl-tempered Hamp's Landing ware, which dates several centuries earlier to the Middle Woodland period. As a result, Herbert and Mathis (1996:154) have voiced the opinion that the term "White Oak" be used to denote the shell-tempered series.

AGRICULTURAL CHIEFDOMS OF THE SOUTH COASTAL REGION (A.D. 1000 - CONTACT)

The agricultural chiefdoms that arose during the last few centuries (A.D. 1000-1500) of southeastern North America Precolumbian history are most commonly known by the term "Mississippian" or "Mississippian-like." The rise of Mississippian chiefdoms is usually characterized as the period when Native American cultures reached their greatest cultural complexity (Bense 1994; Griffin 1967, 1985; Jennings 1974; Muller 1983; Peebles and Kus 1977; Smith 1978, 1986). This complexity is reflected in a hierarchy of site types ranging from single family habitations or "farmsteads" to multi-mound ceremonial centers, a stratified sociopolitical organization that has been broadly compared to chiefdom-level societies, endemic warfare, specialization in the production of various traded commodities (shell, copper, salt), and a heavy reliance on maize (corn) horticulture for subsistence. Earlier subsistence strategies, such as hunting, fishing, and gathering, were used to supplement the agricultural crops.

The rise of Mississippian cultures was also intimately tied to the development of chiefdoms. Chiefdoms were organized hereditarily and were highly structured, socially and economically, which permitted larger numbers of people to share the greater productive potential (and risks) of maize agriculture. The political and economic nature of chiefdoms, however, resulted in continual intragroup competition as many individuals vied for the few highest positions. To be among the ruling elite provided them with greater affluence and prestige. Continual attempts to expand the influence of the chiefdom and bring neighboring groups under economic and political control, increases in population, and a preference for farming floodplain areas, which were limited, led to regular armed conflict.

The Mississippian period (A.D. 1000-1500) is also characterized by the presence of shell-tempered ceramics, although not all areas adapted shell as the preferred pottery tempering agent. This is especially true on the eastern coastal plain where the absence of shell-tempered pottery and the continued use of grit- and sand-tempering has resulted in the description of chiefdom-level societies in the region as "Mississippian-like."

While the powerful Mississippian tradition was widespread in the Southeast, measuring the Mississippian influence on North Carolina Native Americans is difficult. Some evidence of influence exists in the form of pottery types and ornaments connected with the religious and political symbolism of the Mississippian cultural traditions. However, the temple mounds so common to the tradition are absent in the Coastal Plain of North Carolina (except at Town Creek). The cultural alliances between the po-litically and economically powerful groups in North Carolina seem to have been based more on the spoken language than on the forms of tribute and trade networks associated with the Mississippian tradition, to the extent that the Mississippian influence was overshadowed in this area (North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office 1990).

CONTACT PERIOD (A.D. 1524 - 1650)

The first recorded European contact with Native Americans in what is now North Carolina was during the Atlantic coastal voyage of Verrazzano in 1524. Spain, France and England later sent expeditions to North Carolina to explore the area, but it was not until 1585 that the English established a colony on Roanoke Island under the sponsorship of Sir Walter Raleigh. After this venture failed, English settlers entered the Albemarle region from Virginia and, by the middle of the seventeenth century, were well established in North Carolina.

The native populations of North Carolina were largely displaced from the area as the European colonists arrived. Some native groups from the coastal area and the Piedmont voluntarily relocated as the settlers advanced. Other groups were forced to relocate to a few small reservations following bitter conflicts, such as the Tuscarora (1711 and 1712) and Yamassee (1715) Wars. The Native Americans who avoided direct contact with the colonists were, nevertheless, subject to drastically altered political and economic systems. Their cultural traditions were threatened as they became involved in the fur trade. The introduction of European diseases also contributed to the devastation of their former lifeways (North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office 1990).

The largest native groups known to inhabit the region of the Cape Fear River drainage were the Pee Dee, the Cape Fear, and the Waccamaw. All were Siouian language speakers.

In 1715, the Pee Dee lived on the middle course of the Pee Dee River near the present state boundary with South Carolina. "Black River, a lower tributary of the Pee Dee from the west, was formerly called Wenee River, probably another form of the same word, and Winyah Bay still preserves their memory" (Mooney 1970:76 [1894]).

The Cape Fear Indians lived along the river of the same name, which is the next major river north of the Pee Dee. Mooney explained:

The proper name of the Cape Fear Indians is unknown. This local term was applied by the early colonists to the tribe formerly living about the lower part of Cape Fear river in the southeastern corner of North Carolina….The tribe seemed to be populous, with numerous villages along the river. [1970:66 (1894)]

After the Yamasee War, the Cape Fear Indians were removed to South Carolina where they apparently settled in the vicinity of Williamsburg County (Swanton 1946:103). Some South Carolina documents, dated 1808, state that only one mixed-blood woman of the tribe remained by that year, although some of the tribe may have joined the Lumbee or the Catawba (Swanton 1946).

The ancestral Waccamaw were a relatively small tribe of Siouian speakers that lived on the river of that name and on the lower course of the Pee Dee River in close proximity to the Winyah and Pee Dee tribes when the English established themselves in South Carolina in 1670 (Swanton 1946:203). The Waccamaw are among the several modern Native American groups who are recognized today as direct descendants of their prehistoric and early historic ancestors in North Carolina. Another large North Carolinian Indian group of greatly mixed tribal ancestry and racial background are the Lumbee (Paredes 1992:2). Other Native American groups also continue to reside within the boundaries of the state, includ-ing the Eastern Cherokee, the Coharie, and the Haliwa-Saponi (Lerch 1992:45).

THE BATTLE OF MOORES CREEK

BACKGROUND

As the economic and political controversy with Great Britain progressed into open rebellion in the mid-1770s, North Carolina became sharply divided. The legislature, which was popularly elected, openly opposed the royal governor Josiah Martin. By the summer of 1775, the split into two vying groups affected the entire population, with approximately half belonging to the Patriots and the balance composed of Crown officials, wealthy merchants, planters, and other conservatives. Among these conservatives were the Highlanders, a sizable number of people who had immigrated directly from Scotland into North Carolina in the preceding decades (Hatch 1969:1-30).

When the news of the April 1775 skirmishes at Lexington and Concord reached North Carolina a month later, royal authority was further undermined. Governor Martin fled the capital of New Bern and arrived at Fort Johnson on the lower Cape Fear River in June 1775. Only six weeks later, the North Carolina militia forced Loyalists to abandon the fort and escape to the British warship, Cruizer, waiting offshore. The furious governor laid plans for raising an army of 10,000 Loyalists to be made up of Regulators described as "the officers of this county [who are] under a better and honester regulation than any have been for some time" (Hatch 1969:3) and Highlanders of North Carolina. Martin's plans called for this makeshift army to march to the coast and rendezvous with the powerful expeditionary force under Lord Cornwallis, Sir Henry Clinton, and Sir Peter Parker. Their combined forces would, it was firmly believed, reestablish royal authority in the Carolinas (Hatch 1969:3-12).

As soon as the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Dartmouth, approved the plans, Governor Martin began recruiting his army, which was to muster under Brigadier General Donald MacDonald and Lieutenant Colonel Donald McLeod near Cross Creek (Fayetteville). From there, they would march to the coast, provision the British troops arriving by sea, and finally re-conquer the colony. By February 15, 1776, approximately 1,600 men had been assembled (Hatch 1969:11-12).

The Patriots learned of the mass assembly and began gathering their own forces. The militia was mustered under Colonel Richard Caswell and joined the 1st N.C. Continentals under the command of Colonel James Moore. When Tory General MacDonald began marching his Highlanders toward the coast, Moore blocked the movement at Rockfish Creek. MacDonald then rerouted eastward, crossed the Cape Fear River, and proceeded toward the Negro Head Point Road, also called Stage Road, where he believed he would encounter little opposition (Hatch 1969:21-24).

In a counter move, Caswell withdrew from Corbett's Ferry on the Black River in order to "take possession of the Bridge upon Widow Moore's Creek" (King 1937:3). Moore issued orders for Colonel Alexander Lillington to join Caswell, then fell back toward Wilmington, hoping to attack the rear of MacDonald's column as Caswell blocked his forward movement (Hatch: 1969:26-30).

THE BATTLE

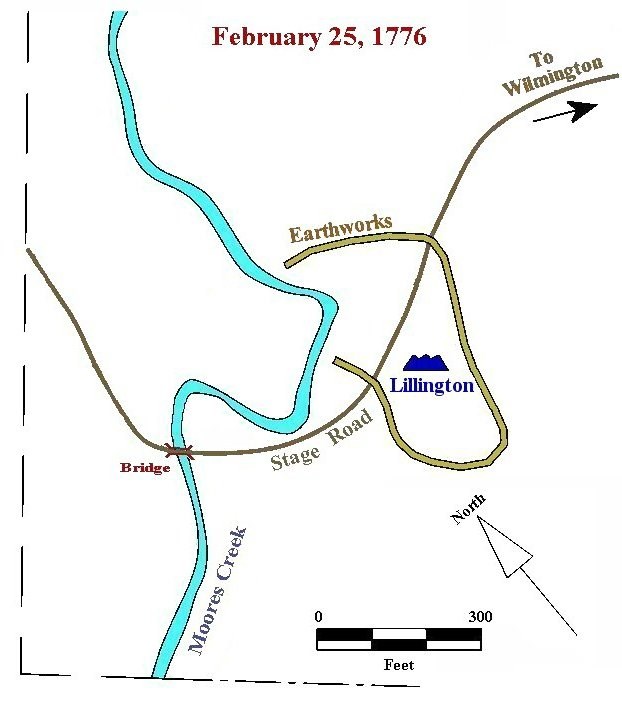

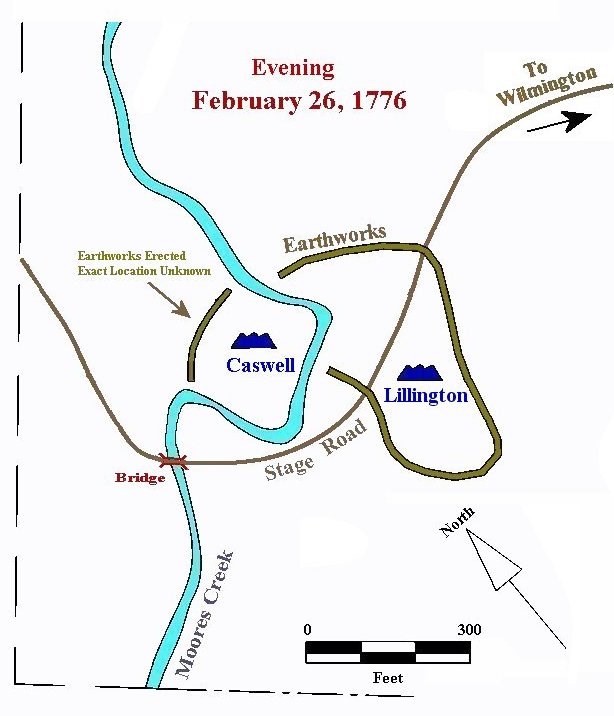

On February 25, 1776, Lillington arrived at Moores Creek Bridge with 150 Wilmington District Minutemen. The murky, silty stream measured more than fifty feet wide. Approximately five to fifteen feet deep, it was subject to tidal fluctuations of several feet. The dark waters wound through swampy land. The creek bottom mixed heavy accumulations of mud and debris and made crossing difficult anywhere in the vicinity except over the narrow bridge. Lillington immediately built a low earthwork on the east side, on a slight rise overlooking the bridge and its approach from the west (Image 2). The next day, Caswell arrived with 850 men, whom he sent across the bridge to throw up entrenchments on the east side (Image 3) (Hatch 1969:34-35).

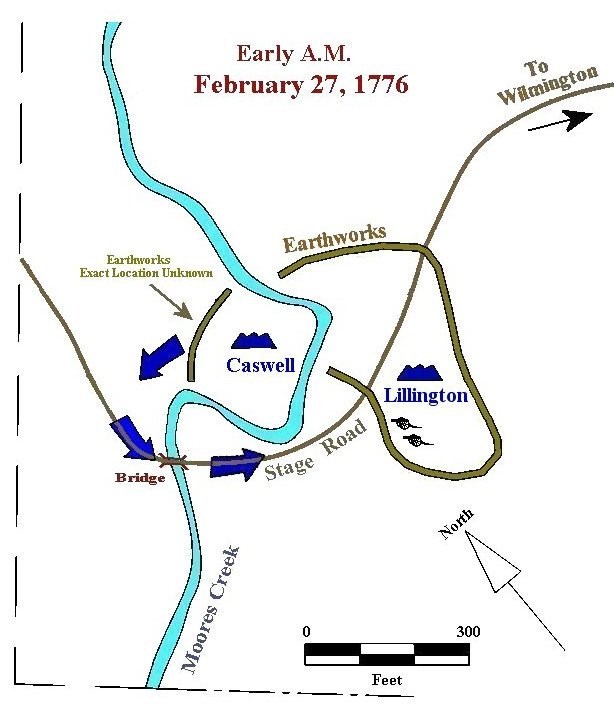

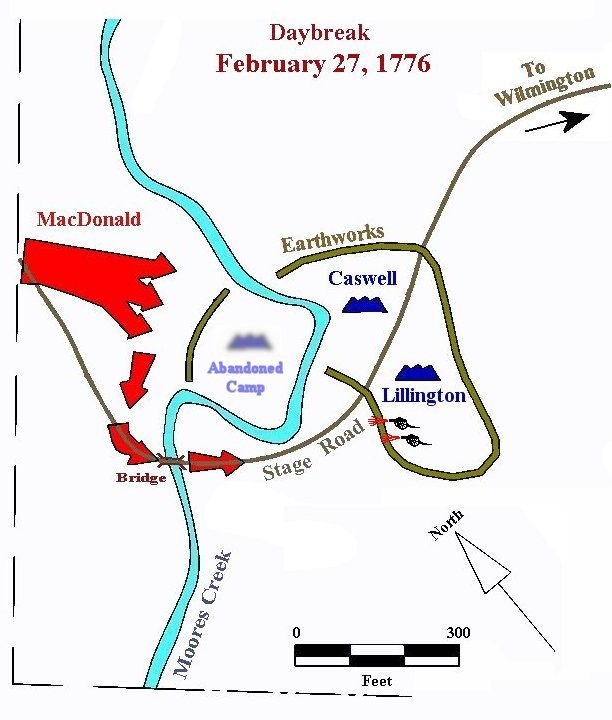

During the night of February 26, 1776, Lillington and his men were camped on the east side of the bridge, Caswell and his men on the west side. MacDonald and his 1,600 Loyalists were camped six miles away, west of the Patriots. MacDonald, aging and ill, advised his council of officers against attack, but the eager McLeod insisted that the reports of the Patriot camp on the near (to their position) side of the creek, or west side, made the campsite a practicable if not an easy target. The younger officers won the debate. McLeod and his Highlanders began their march at one o'clock in the morning on February 27. They quickly became so lost in the swamps that it was close to dawn before they reached the creek in the vicinity of where Caswell had been camped (Hatch 1969:35).

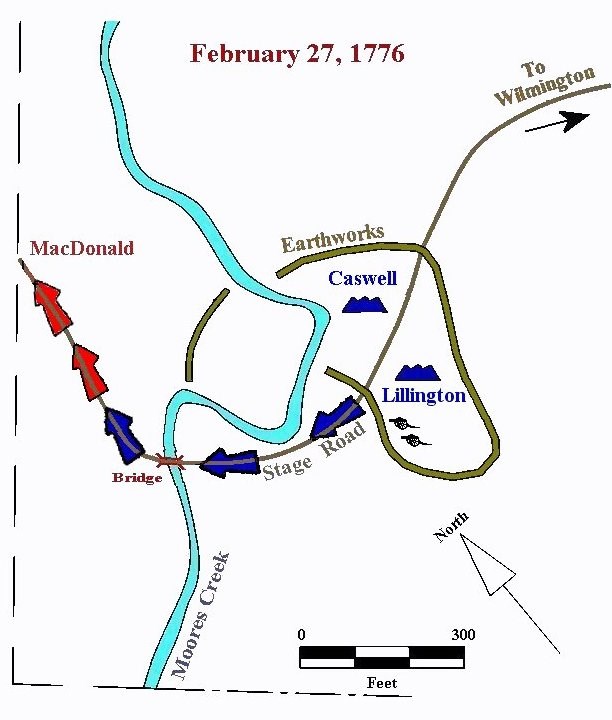

While the Highlanders were lost in the swamps, Caswell and his men had left their camp on the west side position and joined Lillington on the east side behind the better constructed breastworks (Image 4). All that McLeod's men found at daybreak on the west side of the creek were unattended camp fires and empty trenches, which led them to believe the Patriots had fled from the area. A Loyalist patrol leader, Alexander McLean, located the bridge and saw men on the opposite bank but believed they were Highlanders who had already managed to cross the creek during the night. When he loudly called out that he was a friend to the King, the figures frantically scrambled behind the breastworks. At last realizing that the Patriots had not fled the area, he ordered his men to take cover and open fire at the opposite bank (Hatch 1969:35).

When the first shots rang out, McLeod and a company commander, John Campbell, ran southward to McLean's position just west of the bridge. They found that the bridge planking had been removed and the remaining two sleepers greased with soft soap and tallow. To make matters worse, the Patriots were well protected behind their entrenchments on the east side. McLeod and Campbell, nonetheless, led an ill-planned charge across the bridge (Image 5), the men stabbing their swords into the wooden sleepers to retain their footing. The first group got within thirty paces of the Patriot Earthworks and "Old Mother Covington and Her Daughter" (Hatch 1969:40), the trusty artillery pieces of Caswell, before both leaders were hit with musket balls and mortally wounded. McLeod continued shouting encouragement to his men until the hail of bullets ended his life. This first volley by the Patriots swept the bridge clean. Many of the Highlanders, wounded, tumbled into the creek and drowned. Others, thrown into the water by the shock of the sudden volley, were pulled below the water's surface by the weight of their heavy clothing. Those who managed to cross the bridge were shot down. John Grady, who died on March 2, several days after the battle, was the only Patriot to be mortally wounded.

The Highlanders remained on the west side of the creek took cover, but many of the Regulators and other Loyalists fled. The Patriots replaced the bridge planks, began a pursuit (Image 6), eventually rounded up suspected Loyalists, disarmed all the Highlanders and Regulators, and captured valuable spoils, including 1,500 rifles, 350 guns and shot-bags, 150 swords and dirks, and 15,000 British pounds sterling (Hatch 1969:41-45).

However, an account written in part by British General Howe and published with the British Records Colonial Office (1776 C.O. 5, Volume 93:297) describes the battle from the Regulators point of view. A transcription of this correspondence is also kept with the North Carolina Department of Archives and History. In this letter dated April 25, 1776, General Howe and Colonel McLean recount the proceed-ings of a "Body of Loyalist." During these proceedings McLean gave a narrative of events from the Loyalist perspective:

Monday 26th [February] Marched Ten miles, the Army and their Baggage crossed Black River, marched forward and joined the detached parties about eight o-clock in the morning when it was unanimously agreed that Casswell should be attacked immediately the Army being in motion for that Purpose. Intelligence was brought that Casswell had Marched at 8 o'clock the Night before [from a position on the Black River] and had taken possession of the Bridge upon widow Moore's Creek. A party went to examine his abandoned Camp [on the Black River] and found there some horses and Provisions which the Precipitancy of their March made them leave behind them. That evening Mr. Hepburn was sent to the Enemy's Camp with offers of Reconciliation upon their returning to their duty and laying down their Arms, who upon his return to Camp informed us that Casswell had taken up his Ground 6 miles from us upon our side of the Bridge upon widow Moore's Creek and that it was very Practicable to attack them.

A Concel of War being immediately called, it was unanimously agreed that the Enemy's Camp should directly be attacked. The Army was immediately order'd under arms and about one o'clock Tuesday morning the 27th We march'd Six miles with 800 men. In the Front of our Encampment was a very bad Swamp, which took us a good deal of time to pass so that it was within an hour of Daylight before we could get to their Camp. Upon our entering the Ground of their Encampment, we found their fires beginning to turn weak and Concluded that the Enemy were marched. Our Army entered their Camp in three Columns but upon finding that they left their ground, orders were directly given to reduce the Columns and form the Line of Battle within the verge of the Wood (it not being yet day) and the Army should retire a little from the Rear in order to have the Wood to cover us from the sight of the Enemy, the word of Rallement being King George and Broad Swords. Upon hearing a shot on the plain in our front betwixt us and the bridge the whole Army made a Halt and soon thereafter a firing began at the end of the Bridge, it being still dark. The Signals for an Attack was given, which was Three cheers the Drum to beat, the Pipes to play. The Bridge lying above a Cannon Shot in our front upon a deep miry creek Mr. McLean with a party of about 40 men came Accidently to the Bridge, he being a Stranger and it being still dark. He was challenged by the Enemies' Centinels they observing him sooner than he observed them. He answered that he was a friend: they asked to whom. He being a stranger he replyed to the King. Upon his making this reply they squatted down upon their faces to the Ground. Mr. McLean uncertain but they might be some of our own people that had crossed the Bridge, challenged them in Gallic to which they made to Answer. Upon which he fired his own piece and ordered his part to fire. Upon the fireing turning more general in that place Capt. Donald McLeod and Capt. Jno Campbell repaired to the Bridge and endeavored to cross they were both Killed and most of the men that followed them. [McLean's narrative in Howe, 25 April 1776, as cited in Hatch 1969:68-70].

THE OUTCOME

The British sea-borne expedition, which finally arrived in May, was forced to move into an area adjacent to Charleston, South Carolina. In late June of 1776, local Patriot troops were able to successfully repel Sir Peter Parker's land and naval attack at Fort Moultrie, Sullivans Island.

These two encounters-the brief but violent battle at Moores Creek and the repulsion of Parker's attack-were decisive in the final outcome of the Southern campaign of the Revolutionary War. Victory at Moores Creek prevented the Highlanders from joining forces with the British who where gathering along the coast, thus averting a full-scale invasion of the South. Perhaps more importantly, the victory at Moores Creek demonstrated the surprising Patriot strength in the countryside, discouraged the growth of Loyalist sentiment in the Carolinas, and, together with the defeat of Parker, secured the region for the American forces until the British embarked on their second campaign to conquer the South in late 1778.

CREATION OF MOORES CREEK NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD

The first public celebration of the anniversary of the battle at Moores Creek was held in 1856. Public sentiments were thus roused and, in 1857, a monument was erected and dedicated to John Grady, the Patriot who died from wounds received in the battle. In February 1876, Richard P. Paddison purchased two acres of land containing the "Battleground of Moores Creek on which stands the monument of said battle and the old entrenchments" (Maze 1976). Seventeen years later, Paddison lost the property due to delinquent tax payments. On September 4, 1893, Bruce Williams bought the Monument Grounds, which included the battleground and entrenchments, from the Sheriff of Pender County (Walker and Lee 1988).

The purchase of up to twenty acres to be set aside as a public state park in commemoration of the Battle of Moores Creek was authorized by the General Assembly of North Carolina on March 9, 1897. On June 13, 1898, the state of North Carolina purchased the two-acre earthworks from Bruce and Flora Williams. The adjacent eight-acre tract was purchased June 25, 1898, from Peter and Valie Simpson (Walker and Lee 1988). The Moores Creek Monumental Association was incorporated by an act of the North Carolina General Assembly in 1899. Its purpose was to oversee the battlefield and the commemorative celebrations held there. In 1905, the state granted the association an appropriation of $200 to use for clearing the grounds and erecting a pavilion to protect visitors from inclement weather.

In 1907, a series of roads, circular drives, and several buildings were constructed within the area. Two of these roads cut through the remains of the Patriot Earthworks. One corner of the entrenchment was also leveled when a pavilion was constructed there. This structure was built just inside the southeastern corner of the earthworks (King 1937). In addition, a formal garden was placed in the same corner next to the pavilion. A latrine was placed several hundred feet to the rear of the pavilion, which caused a small section of the redoubt to be leveled. A path across the parapet at this point was made over time by visitors walking back and forth. Also, "two sales booths, a jail, a keeper's house, and a stable were constructed" (Maze 1976:3). The state of North Carolina also purchased a twenty-acre tract of land from Peter and Valie Simpson, which adjoined the Monument Grounds on the north and east (Colvin 1907). The Moores Creek Monumental Association administered the park for the next two decades and made numerous other improvements, including clearing land, erecting new buildings, and planting shade trees, flowers, and shrubbery (Maze 1976).

Following a fire that burned the pavilion in 1919, an attempt was made to restore the area in the vicinity of the earthworks to its former appearance (King 1937). The remains of the large pavilion were removed, the circular drive was obliterated, and a footpath was constructed following the old original road (Negro Head Point Road). A new pavilion was built just outside the breastworks in the southeast corner (King 1937).

North Carolina offered to donate the thirty-acre park to the federal government in 1925. On June 2, 1926, Congress authorized the establishment of Moores Creek National Military Park (44 Stat. 684) under War Department administration (Hatch 1969). The War Department administered all National Parks until 1933 when administrative authority was transferred to the Department of the Interior. By Executive Orders 6166 and 6228 of August 10, 1933, the park was transferred to the Department of the Interior and made a unit of the National Park System.

North Carolina conveyed an additional 12.23 acres of land for park use to the United States on November 5, 1951, but the addition was not accepted until February 20, 1953.

Moores Creek National Battlefield was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 (NPS 1976). The archeological remains of the battle and a number of monuments that had been erected by the Moores Creek Monumental Association in the early part of the twentieth-century were classified as "Historic Structures" in the National Register Bulletin 16A (NPS 1991:15).

The following list briefly identifies these sites:

HS-1: Patriot Earthworks.

HS-2: Forward Earthworks or Lillington's Earthworks.

HS-3: Negro Head Point Road (originally Colonial Road or Old Stage Road). This site consists of traces of a roadway that dates from about 1743.

HS-4: Patriot or Grady Monument. Erected to commemorate John Grady, the only Patriot to die of wounds received in the Battle of Moores Creek. The foundation for this monument was laid in 1857, and the entire monument was relocated in 1974 within the Patriot Earthworks.

HS-5: Heroic Women Monument, also known as the Slocumb Monument. Erected in 1907, this white marble statue of a female form honors both the heroic women of Lower Cape Fear and Mary Slocumb. In 1929, Mary (Molly or Polly as she was sometimes called) and her husband Ezekiel were exhumed and reinterred near the monument.

HS-6: Monument commemorating the Loyalist army. This large granite monument was erected in 1909 and relocated some four hundred feet south in 1974.

HS-7: Stage Road Monument. Erected in 1911, this granite structure has an inscription describing the battle and a bas-relief cannon. It was moved from within to outside the earthworks in 1942.

HS-8: The James F. Moore monument. In honor of the first president of the Moores Creek Battleground Association, this monument was erected in 1912. It is made of dressed granite in the shape of an obelisk. Damage caused by high winds in 1944 was repaired in January 1945.

HS-9: Bridge Monument. This granite structure erected in 1931 stands beside the Colonial Road near the location of the original bridge over Moores Creek.

HS-10: The entrenchments of Caswell's Camp.

Newly acquired lands were added to the park once more in 1986, including lands west of Moores Creek, a strip of land north of Patriots Hall, and another strip of land east of the park. These lands increased the park property from 42.23 to 86.52 acres. The additions were nominated and accepted by amendment to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 (NPS 1986). The small entrenchments of Caswell's Camp on the west bank of Moores Creek (Historic Structure 10) were also accepted to the Register at this time, although no trace of the camp or the entrenchments has ever been located archeologically.

In 1996, another amendment to the National Register of Historic Places was added for Moores Creek National Battlefield. Two boundary markers erected by Moores Creek Monumental Association between 1897 and 1910 were nominated and accepted. "The markers are two granite slabs (6" x 5" x 6" high and 6" x 5" x 1' high) with rock-faced sides and smooth-faced tops. MCMA is inscrbed on the tops. The markers are located along the park's southern boundary off a fire trail" (NPS 1996:3).

References

Anderson, David G.

1990 The Paleoindian Colonization of Eastern North America: A View from the Southeastern United States. In Early Paleoindian Economies of Eastern North America, edited by Kenneth B. Tankersley and Barry L. Isaac, pp. 163-216. Research in Economic Anthropology, Supple-ment 5. JAI Press, Greenwich, Connecticut.

Anderson, David G. (editor)

1996 Indian Pottery of the Carolinas: Observations from the March 1995 Ceramic Workshop at Hobcaw Barony. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

Anderson, David G., Charles E. Cantley, and A. Lee Novick

1982 The Mattassee Lake Sites: Archeological Investigations along the Lower Santee River in the Coastal Plain of South Carolina. Interagency Archeological Services Division, National Park Service, Atlanta.

Anderson, David G., Lisa D. O'Steen, and Kenneth Sassaman

1996 Environmental and Chronological Considerations. In The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman, pp. 3-15. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Anderson, David G., Kenneth E. Sassaman, and Christopher Judge

1992 A History of Paleoindian and Early Archaic Research in the South Carolina Area. In Paleoin-dian and Early Archaic Period Research in the Lower Southeast: A South Carolina Perspective, edited by David G. Anderson, Kenneth E. Sassaman, and Christopher Judge, pp. 7-18. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

Bense, Judith A.

1994 Archaeology of the Southeastern United States: Paleoindian to World War I. Academic Press, New York.

Brose, David S., and N'omi Greber (editors)

1979 Hopewell Archaeology: The Chilicothe Conference. Kent State University Press, Kent.

Cambron, James W., and David C. Hulse

1975 Handbook of Alabama Archaeology, Part 1, Point Types (revised). Archaeological Research Association of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Clausen, C. J., A. D. Cohen, C. Emeliani, J. A. Holman, and J. J. Stipp

1979 Little Salt Spring, Florida: A Unique Underwater Site. Science 203:609-614.

Coe, Joffre L.

1964 The Formative Cultures of the Carolina Piedmont. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54(5). Philadelphia.

Coe, Joffre L., H. Trawick Ward, Martha Graham, Liane Navey, S. Homes Hogue, and Jack H. Wilson Jr.

1982 Archaeological and Paleo-osteological Investigations at the Cold Morning Site, New Hanover County, North Carolina. Submitted to Interagency Archeological Services (Atlanta). Research Laboratories of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Colvin, Henry A.

1907 A Plan of Three Tracts of Land at the Moores Creek Battle Ground. On file, Moores Creek National Battlefield, Currie, North Carolina.

DeJarnette, David L., Edward B. Kurjack, and James W. Cambron

1962 Excavations at the Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 8(1-2):1-124.

Delcourt, Paul A., and Hazel R. Delcourt

1981 Vegetation Maps for Eastern North America: 40,000 Years b.p. to the Present. In Geobotany II, edited by Robert C. Romans, pp. 123-166. Plenum Press, New York.

Dunbar, James S., and S. David Webb

1996 Bone and Ivory Tools from Submerged Paleoindian Sites in Florida. In The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman, pp. 331-353. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Goodyear, Albert C., III

1974 The Brand Site: A Techno-functional Study of a Dalton Site in Northwest Arkansas. Research Series 7, Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

1982 The Chronological Position of the Dalton Horizon in the Southeastern United States. American Antiquity 47:382-395.

Griffin, James B.

1967 Eastern North American Archaeology: A Summary. Science 156(3772):175-191.

1985 Changing Concepts of the Prehistoric Mississippian Cultures of the Eastern United States. In Alabama and the Borderlands: From Prehistory to Statehood, edited by R. Reid Badger and Lawrence A. Clayton, pp. 40-63. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Haag, William C.

1958 The Archeology of Coastal North Carolina. Coastal Studies Series 2, Louisiana State Univer-sity, Baton Rouge.

Hatch, Charles E., Jr.

1969 The Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. Office of History and Historic Architecture, Eastern Ser-vice Center, National Park Service, Washington.

Herbert, Joseph M., and Mark A Mathis

1996 An Appraisal and Re-Evaluation of the Prehistoric Pottery Sequence of Southern Coastal North Carolina. In Indian Pottery of the Carolinas: Observation from the March 1995 Ce-ramic Workshop at Hobcaw Barony, edited by David G. Anderson, pp. 136-189. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

House, John H., and David L. Ballenger

1976 An Archaeological Survey of the Interstate 77 Route in the South Carolina Piedmont. Research Manuscript Series 104, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Jennings, Jesse

1974 Prehistory of North America. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Justice, Noel D.

1987 Stone Age Spear and Arrow Points of the Midcontinental and Eastern United States. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

King, Clyde B.

1937 Special Report on the Breastworks at the Moores Creek National Military Park. National Park Service, Washington.

Ledbetter, R. Jerald

1995 Archaeological Investigations at Mill Branch Sites 9WR4 and 9WR11, Warren County, Geor-gia. Interagency Archeological Services, National Park Service, Atlanta.

Lerch, Patricia Barker

1992 State-Recognized Indians of North Carolina, Including a History of the Waccamaw Sioux. In Indians of the Southeastern United States in the Late 20th Century, edited by J. Anthony Pare-des, pp. 44-71. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Lewis, Thomas M. N.

1954 The Cumberland Point. Bulletin of the Oklahoma Anthropological Society 11:7-8.

Lilly, Thomas G., and Joel D. Gunn

1996 An Analysis of Woodland and Mississippian Period Ceramics from Osprey Marsh, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. In Indian Pottery of the Carolinas: Observation from the March 1995 Ceramic Workshop at Hobcaw Barony, edited by David G. Anderson, pp. 63-115. Council of South Carolina Professional Archaeologists, Columbia.

Loftfield, Thomas C.

1976 "A Brief and True Report." An Archaeological Interpretation of the Southern North Carolina Coast. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

MacDonald, George F.

1983 Eastern North America. In Early Man in the New World, edited by R. Shutler, pp. 97-108. Sage, Beverly Hills.

Mason, Ronald J.

1962 The Paleo-Indian Tradition in Eastern North America. Current Anthropology 3:227-283.

Maze, Terry E.

1976 History of Earthworks: Moores Creek National Military Park. Ms. on file, Southeast Archeo-logical Center, National Park Service, Tallahassee.

Michie, James L.

1977 Early Man in South Carolina. Ms. on file, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and An-thropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Milanich, Jerald T.

1971 The Alachua Tradition of North-central Florida. Contributions of the Florida State Museum, Anthropology and History 17, University of Florida, Gainesville.

1972 Excavations at the Richardson Site, Alachua County, Florida: An Early 17th Century Potano Indian Village (with notes on Potano culture change). Bureau of Historic Sites and Properties, Division of Archives, History and Records Management, Bulletin 2, pp. 35-61. Florida De-partment of State, Tallahassee.

Mooney, James

1970 The Siouan Tribes of the East. Johnson Reprint, New York. Originally published, GPO, Wash-ington, 1894.

Morse, Dan F.

1971a Recent Indications of Dalton Settlement Pattern in Northeast Arkansas. Southeastern Archaeo-logical Conference Bulletin 13:5-10.

1971b The Hawkins Cache: A Significant Dalton Find in Northeast Arkansas. Arkansas Archaeolo-gist 12(1):9-20.

1973 Dalton Culture in Northeast Arkansas. Florida Anthropologist 26(1):23-38.

Morse, Dan F., and Phyllis A. Morse

1983 Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. Academic Press, New York.

Muller, Jon

1983 The Southeast. In Ancient North Americans, edited by Jesse D. Jennings, pp. 373-419. W. H. Freeman, New York.

National Park Service (NPS)

1976 National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form (for Moores Creek National Battlefield). National Park Service, Washington,

1986 Amendment to the National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form (for Moores Creek National Battlefield). National Park Service, Washington.

1991 How to Complete the National Register Registration Form. National Register Bulletin 16A, National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division, Washington.

1996 Amendment to the National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form (for Moores Creek National Battlefield). National Park Service, Washington.

North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

1990 Legacy: A Preservation Guide into the Twenty-First Century for North Carolinians, North Carolina Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan for the 1990's. Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh.

Oliver, Billy L.

1981a The Point, the Pendulum, and Perception: Extracting Meaning from the Cold Stones of Real-ity. Paper presented at the 38th annual meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Asheville, North Carolina.

1981b The Piedmont Tradition: Refinement of the Savannah River Stemmed Point Type. Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

1985 Tradition and Typology: Basic Elements of the Carolina Projectile Point Sequence. In Struc-ture and Process in Southeastern Archaeology, edited by Roy S. Dickens and H. Trawick Ward, pp. 195-211. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

O'Steen, Lisa D., R. Jerald Ledbetter, Daniel T. Elliott, and William W. Barker

1986 Paleoindian Sites of the Inner Piedmont of Georgia: Observations of Settlement in the Oconee Watershed. Early Georgia 13:1-63.

Paredes, J. Anthony (editor)

1992 Indians of the Southeastern United States in the Late 20th Century. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Peebles, Christopher S., and Susan M. Kus

1977 Some Archaeological Correlates of Ranked Societies. American Antiquity 42:421-448.

Phelps, David Sutton

1968 Thom's Creek Ceramics in the Central Savannah River Locality. Florida Anthropologist 21(1):17-30.

1976 Archaeological Survey of the Swift Creek Watershed. In An Environmental Assessment and Impact Analysis for the Swift Creek Watershed, Pitt, Beaufort, and Craven Counties, North Carolina. Wm. F. Freeman, High Point, North Carolina.

1983 Archaeology of the North Carolina Coast and Coastal Plain: Problems and Hypotheses. In The Prehistory of North Carolina: An Archaeological Symposium, edited by Mark A. Mathis and Jeffrey J. Crow, pp. 1-49. North Carolina Division of Archives and History, Raleigh.

Sassaman, Kenneth E., and David G. Anderson

1995 Middle and Late Archaic Archaeological Records of South Carolina: A Synthesis for Research and Resource Management. Savannah River Archaeological Research Papers 6, South Caro-lina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Sears, William H., and J. B. Griffin

1950 Fiber-Tempered Pottery of the Southeast. In Prehistoric Pottery of the Eastern United States, edited by James B. Griffin, pp. 1-12. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Sellards, E. H.

1952 Early Man in America. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Shott, Michael J.

1986 Settlement Mobility and Technological Organization among Great Lakes Paleo-Indian Fora-gers. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Simons, Donald B., Michael J. Shott, and Henry T. Wright

1984 The Gainey Site: Variability in a Great Lakes Paleo-Indian Assemblage. Archaeology of Eastern North America 12:266-279.

Smith, Bruce D.

1978 Variation in Mississippian Settlement Patterns. In Mississippian Settlement Patterns, edited by Bruce Smith, pp. 479-503. Academic Press, New York.

1986 The Archaeology of the Southeastern United States: From Dalton to de Soto, 10,500-500 b.p. In Advances in World Archaeology 5, edited by Fred Wendorf and Angela Close, pp. 1-92. Academic Press, New York.

Soday, Frank J.

1954 The Quad Site: A Paleo-Indian Village in North Alabama. Tennessee Archaeologist 10:1-20.

South, Stanley

1976 An Archaeological Survey of Southeastern North Carolina. Notebook 8, South Carolina Insti-tute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Steen, Carl, and Chad Braley

1994 A Cultural Resources Survey of Selected (FY92) Timber Harvesting Areas on Fort Jackson, Richland County, South Carolina. Gulf Engineers and Consultants, Baton Rouge, and South-eastern Archeological Services, Athens. Submitted to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Savannah District, and The Directorate of Engineering and Housing, Fort Jackson.

Swanton, John R.

1946 The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bulletin 137, Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

Trinkley, Michael, William B. Barr, and Debi Hacker

1996 An Archaeological Survey of the 230 HA Camp Mackall Drop Zone and 70 HA Manchester Road Tract, Fort Bragg, Scotland and Cumberland Counties. Chicora Research Contribution 187, Chicora Foundation, Columbia, South Carolina.

Walker, John W., and Jerry W. Lee

1988 A Study of Historic, Topographic, and Archeological Data Pertaining to the Revolutionary War Period Earthworks at Moores Creek National Battlefield, North Carolina. Ms. on file, Southeast Archeological Center, National Park Service, Tallahassee.

Webb, Clarence H., J. L. Shiner, and E. W. Roberts

1971 The John Pearce Site (16CD56): A San Patrice Site in Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Bulletin of the Texas Archaeological Society 42:1-49.

Webb, S. David, Jerald T. Milanich, Roger Alexon, and James S. Dunbar

1984 A Bison antiquus Kill Site, Wacissa River, Jefferson County, Florida. American Antiquity 49:384-392.

Widmer, Randolph J.

1976 Archaeological Investigations at the Palm Tree Site, Berkeley County, S.C. Research Manu-script Series 103, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Wilde-Ramsing, Mark

1978 A Report on the New Hanover Archaeological Survey: A CETA Project. Ms. on file, Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh.

Wormington, H. Marie

1957 Ancient Man in North America. Popular Series 4, Denver Museum of Natural History. Peer-less, Denver.

Last updated: February 12, 2020