______________________________

Fort Pulaski National Monument

CULTURAL OVERVIEW

By Lou Groh (2000)

______________________________

NATIVE AMERICAN ARCHEOLOGY AND CULTURE HISTORY

Although Native American populations have occupied Georgia from the Paleoindian period to the present, Fort Pulaski National Monument has not yet been archeological surveyed for evidence of past Native American activities that may have occurred within its boundaries. It is therefore necessary to rely on cultural chronologies that have been developed from archeological investigations conducted elsewhere in the Savannah River Valley to provide a framework for discussing those Native American cultures that might be present at Fort Pulaski National Monument.

Paleoindian (ca. 10,000 - 8000 B.C.)

The earliest known Native American populations to inhabit the Americas are generally referred to as the Paleoindians. During the late Altonian Subage of the Wisconsinan Age, forty thousand years ago, the Laurentide Ice sheet extended south into what is today the Great Lakes Region. Global water was taken up by the massive ice sheets, exposing portions of the continental shelf which are now under several hundred feet of water (Delcourt and Delcourt 1981:141). Periodically, during extreme intervals of glacial freezing, a submerged land bridge connecting Siberia to Alaska was exposed in the Bering Sea. It is generally believed that Paleoindians migrated across the Bering Straits land bridge during these low water intervals.

The climate and environment during the Paleoindian period was in transition and generally colder than today. Along the southern Atlantic Coastal Plain from South Carolina to northern Florida, the terrain was covered by the Oak-Hickory-Southern Pine Forest. The period of Late Wisconsinan Continental Glaciation peaked at approximately 18,000 years ago. At that time, water was stored in the massive continental ice sheets, resulting in sea levels approximately 100 meters lower than today. Around 12,000 years ago, a period of warming occurred in eastern North America that resulted in a minor retreat of the polar ice sheets. During the retreat, ice-free corridors were exposed along the edges of some of the major ice sheets. It is expected that Paleoindians spread across North America by using the ice-free corridors.

Based on archeological evidence recovered in the Southeastern United States, Paleoindians are described as nomadic, egalitarian bands composed of several nuclear or extended families (Anderson 1990a; Morse and Morse 1983). Archeologists have on many occasions described Paleoindians as big game hunting specialists. Extinct Pleistocene megafauna such as the giant ground sloth, mastodon, and bison were presumably among the big game sought after by Paleoindian hunters in the Southeast. Although direct evidence is meager, there are two instances in Florida where Paleoindians have been linked to the hunting of megafauna. The first consists of a speared giant tortoise from Little Salt Springs, Florida (Clausen et al. 1979), and the second is a Bison antiquus skull with a projectile point embedded in its forehead from the Wacissa River, Florida (Webb et al. 1984). Controversy still exists, however, among the archeological community regarding the degree to which megafauna played a role in the subsistence strategies of Paleoindian populations. Pleistocene megafauna were nearing extinction during the Early Paleoindian period throughout North America, and major exploitation of megafauna is not documented in the archeological record of Southeastern United States as it is in other areas of the North America such as the Great Plains and Canada. Current research regarding subsistence strategies of the Paleoindians has, therefore, shifted focus from the big game hunter theory to a more generalized and developed synthesis of Paleoindian adaptation to local resources such as the white tailed deer, other smaller mammals, and local plants for the Southeastern United States (Bense 1994:44; Martin and Klein 1984; Mead and Meltzer 1984; Meltzer and Smith 1986).

While most Paleoindian sites in the Southeastern United States are located on the floodplains of major rivers, some sites occurring at upland edges. Anderson (1995a:148) states that large areas of the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plain appear to have been only minimally utilized. Submerged sites found on the continental shelf and coastal shorelines of Southeastern United States, however, confirm that Paleoindians frequented these exposed landforms (Dunbar and Webb 1996:351-354).

Unlike the Atlantic continental shelf where submerged Paleoindian sites are found, evidence for the use of the Sea Islands during the Paleoindian period is sparse. Fluted points are rarely found on or near the Sea Islands of Georgia, even though these areas would have been well inland 12,000 years ago, since sea levels were 70 or more meters lower than present. Several surveys conducted during the 1970s and 1980s (Braley et al. 1985:8, 94; DePratter 1978; Kirkland 1979; Pearson 1977) of the Sea Islands of Georgia found that none of the sites dated earlier than the Late Archaic period (Anderson et al. 1990:25). It is, therefore, unlikely that Paleoindian sites will be found within Fort Pulaski National Monument.

The Paleoindian period has been subdivided into three broad temporal groupings: Early (10,500 to 9000 B.C.), Middle (9000 to 8500 B.C.), and Late Paleoindian (8500 to 8000 B.C.) (Anderson 1990a; Anderson and Sassaman 1996; O'Steen et al. 1986:9). The divisions are based on changes in lithic technology and presumably changes in subsistence strategies. The earliest evidence of Paleoindian occupation in the Savannah River Valley, however, is 9500 B.C. (David Anderson, personal communication 1997).

Early Paleoindian (ca. 10,000-9000 B.C.)

The temporally diagnostic stone tool associated with the Early Paleoindians is called the Clovis projectile point. In the Southeast, subtle variations to the standard western lanceolate Clovis have been labeled “Clovis-like” including Eastern Clovis and Gainey (Anderson et al. 1996:9; MacDonald 1983; Mason 1962; Shott 1986; Simons et al. 1984). The size may vary by several inches, but Clovis points all share a distinct lanceolate-shape that is narrow-bladed, has a concave base, and a groove or flute which rarely extends more than one third up the center of the bifacial tool (Justice 1995:17).

Roughly fifty Clovis projectile points have been found along the approximately 250 miles of the Savannah River drainage (Anderson 1990a; Goodyear et al. 1990). The Taylor Hill site, located in the Savannah River Valley near Augusta, has produced the highest density of Paleoindian cultural materials to date (Elliott and Doyon 1981). A total of 565 tools were recovered during the fieldwork which included a controlled surface collection over a 18,000 m2 area and twelve test units consisting of eleven 2 x 2 m test units and one 1 x 1 m unit. Only one of the 565 tools was a “Clovis like” point (Anderson et al. 1990:29).

Smaller fluted points that appear to be extensively resharpened Clovis points, are sometimes referred to as Clovis Variants (Michie 1977:62-65). They probably represent a transitional stage of lithic technology between the Early and Middle Paleoindian periods (Anderson et al. 1990:6).

Middle Paleoindian (ca. 9000-8500 B. C.)

Temporal indicators of the Middle Paleoindian period consists of smaller fluted points, unfluted lanceolate points, and fluted or unfluted points with broad blades and constricted haft elements (Anderson et al. 1990:6; Anderson et al. 1996:11-12). These point types include Cumberland, Suwannee, and Simpson types and Clovis Variants. Cumberland points are the most common types recovered in the Mid South. They are characterized by Lewis (1954) as being narrow, deeply fluted, slightly waisted lanceolates with faint ears and a slightly concave base. Beaver Lake and Quad types are sometimes assigned to the Late or transitional Middle/Late Paleoindian period.

Some evidence for Middle to Late Paleoindian occupation along the Savannah River is also found at the Taylor Hill site. During excavations there in 1981, Elliott and Doyon recovered one fluted preform and two Dalton points. Other lithic tools recovered include spokeshaves, gravers, hafted end scrapers, side scrapers, and a range of multi-functional tools. Large quantities of lithic debitage recovered at the site were interpreted to be evidence of tool manufacturing and maintenance (Anderson et al. 1990:29).

Late Paleoindian (ca. 8500-8000 B.C.)

The projectile points associated with the Late Paleoindian period in eastern Georgia are assignable to the Dalton cluster (Justice 1995:35). The Dalton cluster includes Beaver Lake, Quad and Dalton projectile points, examples of which have been recovered from the Savannah River drainage. Beaver Lake projectile points exhibit recurved blade edges, concave bases, and basal ears (Cambron and Hulse 1960; 1969; DeJarnette et al. 1962:47). They compare with the Cumberland style but totally lack fluting and exhibit only moderate basal thinning (Justice 1995:35). Quad projectile points were first recovered from the Quad site in northern Alabama (Soday 1954:9). They are short lanceolate forms with distinct basal ear projections, pronounced basal thinning, and are sometimes fluted (Cambron and Hulse 1969:98; Cambron and Waters 1959:79; Justice 1995:36). These forms are similar to Beaver Lake overall, although Quad points are shorter relative to width and have wide ears and an abrupt stubby appearance at the tip of the blade (Bell 1960:80; Justice 1995:36). Dalton projectile points are characterized by their lanceolate or trianguloid-blade with serrated edges and concave bases (Chapman 1948:13; Justice 1995:40). Dalton points can also be recognized by the parallel to slightly incurvate lateral margins that are smoothed by heavy grinding. The basal concavity is deep and thinned with one or more thinning flakes detached from a beveled striking platform (Morse 1971:13; Justice 1995:40). Greenbrier and Hardaway side notched projectile points appear to be transitional between the Late Paleoindian and the Early Archaic periods.

Archaic (ca. 8000-1000 B.C.)

The 7000 year interval following the Paleoindian period is referred to by archeologists as the Archaic period. Cultural innovations introduced by Archaic populations include the first construction of mounds and earthworks, the formation of large settlements and sites, the adoption of horticulture, and the establishment of long-distance trade. The major technological changes attributed to the Archaic period include the use of notched and stemmed triangular projectile points, containers of stone or pottery, and ground and polished stone tools (Bense 1994:62). The Archaic period has also been subdivided into Early (8000 to 6000 B.C.), Middle (6000 to 3000 B.C.), and Late Archaic (3000 to 1000 B.C.) time periods.

Early Archaic (ca. 8000-6000 B.C.)

The lithic technology of the Early Archaic period changed dramatically from that of the preceding Paleoindian period. The large lanceolate points that dominated the Paleoindian period were replaced by smaller triangular-shaped projectile points with notched bases. Some archeologists attribute the reduction in the size of the points to the introduction of the spear thrower or atlatl. The atlatl functions as an extension to the human arm, which when used increases the velocity, accuracy, and distance that the projectile can be thrown. A more common interpretation for the reduction in size of the Early Archaic points is simply the activity of reshaping larger points. The temporally diagnostic projectile point of the Early Archaic period in Georgia is the Kirk Corner Notched, although the Big Sandy Side Notched proceeds the Kirk Corner Notched in many areas of the Southeast (Bense 1994:65-66). The Kirk Corner Notched points are characterized as being large triangular blades with straight or slightly rounded bases and bifacially serrated blade edges. The blade edges are occasionally beveled (Broyles 1971:65; Coe 1964; Justice 1995:71).

Early Archaic populations are generally portrayed as having band or macroband forms of organization. For most of the year, they probably lived in small camps scattered along a single river drainage. This appears to be the case for the Early Archaic sites located along the middle and upper Savannah River Valley where extended families hunted and gathered foods from the river valley. During the fall, when food was more plentiful, it is theorized that larger groups congregated for a short time near the intersection of the Coastal Plain and the Piedmont, or what is commonly called the Fall Line. Archeological evidence suggests that the Fall Line camps were used for preparing hides, heavy-duty woodworking, tool manufacturing and building structures. These annual congregations were presumably very important social events and may have included groups from neighboring river valleys. It is further suggested that the annual gatherings may also have functioned as a time to find and exchange mates (Anderson and Hanson 1988; Anderson et al. 1992).

Middle Archaic (ca. 6000-3000 B.C.)

During the mid-Holocene Hypsithermal Interval from 6,000 to 2,000 B.C. a major vegetation change occurred in the Midwestern and Southeastern United States. Increased strength in the prevailing westerly winds resulted in warmer and dryer conditions during the Hypsithermal Interval. At approximately 3000 B.C. the sea level returned to its modern position. On the sandy uplands of the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plains the oak and hickory forests were replaced by southern pine with the Oak-Hickory-Southern Pine Forest restricted to the Piedmont and the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains. Along the present coasts extensive swamps and marshes developed (Delcourt and Delcourt 1981:150).

The mid-Holocene climatic change resulting in recognizable and successful cultural adaptations to the new forest communities and related animal populations. Six new types of projectile points Eva, White Springs, Stanly, Morrow Mountain, Benton, and Guilford types were introduced into the Mid-South during the Middle Archaic. Because the normal geographical range of the Eva, White Springs, and Stanly points does not extend into the Coastal Plain of Georgia, they are rarely recovered from the local area. Morrow Mountain, Benton, and Guilford points, however, are well represented.

Morrow Mountain points are subdivided into Morrow Mountain I and II, based mostly on stem to base ratio. Morrow Mountain I is described as a small point with a broad triangular blade and a short, pointed, contracting stem. Excurvate blades are typical, although straight and incurvate blade edges also occur. Serration is sometimes exhibited on the blade edges. Maximum width occurs at the shoulder. The stem of Morrow Mountain I is shorter and tapers inward from a wide and sloping shoulder. Infrequently, grinding may occur on the shoulder and stem. The blade of the Morrow Mountain II is long and narrow with straight or slightly rounded sides. Some specimens tend to flare or curve outward at the shoulder. Shortened blades are a result of blade reworking. Stems of these points are long and tapered with a more definite break at the shoulder and haft juncture than is described for Morrow Mountain I (Coe 1964:37-43; Justice 1995:105).

Benton Stemmed points are described as being large points with the presence of oblique parallel flaking occurring on the blade. Edge beveling of the base and notch, and sometimes of the blade is also a distinctive feature of these points. The edge bevel is bifacially flaked so that the cross section of the haft exhibits a flattened hexagon shape. This contrasts with the rhomboidal blade shapes characteristic of certain Early Archaic projectile points (Justice 1995:111).

Although Justice (1995:111) described the normal distribution of the Benton Stemmed Cluster as being confined to northern Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky, projectile points very similar to but somewhat larger than Benton Stemmed, called “Benton like”, are recovered from the Savannah River Valley (David Anderson, personal communication 1997). The “Benton like” points blade morphology is apparently less variable than the haft elements. Blade length varies considerably, but overall Benton represents a lanceolate blade tradition. This variation probably relates to lateral resharpening of blade margins, with the thickest, most narrow blades reflecting late stages of edge retouch (Sassaman et al. 1990:156). Sassaman (1990) suggests that some Benton Stemmed points from Tennessee and Mississippi were no longer used as subsistence tools. They were recovered from mortuary contexts and ceremonial cashes. These points are very similar to those recovered from the Savannah River Valley and may be the result of exchange between the groups.

Sassaman (1985) has also defined a point type recovered from the Pen Point site, which is located in the Middle Savannah River drainage, as “MALA” (Middle Archaic-Late Archaic) points. MALA’s are described as being relatively thick in proportion to width with straight blade edges and broad, straight, expanding or notched stems. Haft areas are steeply flaked producing a bevel-like appearance on some examples (Ledbetter 1995:54-55). The points are described as similar to the Guilford types that are recovered from the Piedmont. Guilford and Halifax projectile points seem to be transitional between the Middle and Late Archaic (Justice 1995:163).

Several technological advancements were made during the Middle Archaic in the manufacture of ground and polished stone tools. Grooved axes, atlatl weights, and hooks were added to the Archaic tool kit, and ornaments such as shell, bone and stone beads and pendants became increasingly popular (Bense 1994:78). Unfortunately, as is the case with earlier sites, the organic components of the Middle Archaic artifact assemblages are seldom preserved in the archeological record. Exceptions to this are wet sites such as Hontoon Island (Purdy 1979,1980,1981) and Windover (Doran and Dickel 1988) and shell middens (Schwadron 1997). These types of sites are more likely to occur at Fort Pulaski National Monument and are known to provide excellent preservation of friable artifacts.

During the first portion of the Middle Archaic, the settlement patterns in the Southeast appear to have remained much the same as in the Early Archaic. After approximately 5000 B.C. in at least three areas of the Southeast, the lower Tennessee River Valley, the upper Tombigbee Valley, and the eastern Florida Peninsula, settlement patterns changed considerably. Long term occupations referred to by some as base camps are evidenced for the first time. The camps are recognized by the presence of thick deposits of midden containing abundant plant and animal remains. Domestic features such as pits and hearths were also recovered during archeological investigations of the midden areas. In some instances, the midden heaps were also used for burials (Bense 1994:82). In the lower Savannah River drainage low earthen mounds are seen for the first time during the Middle Archaic period (David Anderson, personal communication 1997).

Late Archaic (ca. 3000-1000 B.C.)

By the beginning of the Late Archaic period, environmental conditions in Georgia were stabilizing, which resulted in sea level and climatic conditions much as they are today. The modern barrier islands emerged along much of the coastline and modern coastal ecosystems developed in many areas. Sediments were swept down river which formed mud flats and marshes at the mouths of many rivers (Bense 1994:85; DePratter 1991). It is likely that the islands that form Fort Pulaski National Monument were sufficiently developed to support small human populations during this time period.

Archeological evidence is sufficient for the Late Archaic to suggest that large base camps located on the flood plains and along the coastal strip were more common than during the Middle Archaic. The higher degree of sedentism is attributed to the change in the climate that brought about a change in available food sources. The coastal base camps in the area of the Savannah River drainage were generally ring-shaped shell middens. Over thirty shell rings have been recorded along the eastern seaboard from Cape Fear, North Carolina to northeast Florida.

The projectile points most synonymous with the Late Archaic in the Savannah River area, are the Savannah River Stemmed and Small Savannah River Stemmed types. Savannah River Stemmed points are described as being large trianguloid-blade forms with broad stems (Cambron and Hulse 1969:104; Claflin 1931:31-39; Coe 1964:44-45; Oliver 1981). The blade is often fairly long relative to stem length and exhibits straight to excurvate edges and wide thinning flake scars. The shoulders tend to be angular, placed at a right angle to the stem, and are never barbed. A straight sided stem is typical, although stem characteristics vary from slightly expanding to mildly contracting. The basal edge is typically concave, although straight to slightly rounded basal edges also occur. The raw materials used for Savannah River Stemmed projectile points include chert, quartzite, quartz, argillite, rhyolite and andesite, which are available in the Appalachian area (Justice 1995:163). Small Savannah River Stemmed points are usually manufactured of local chert or quartz (Justice 1995:163).

On the Atlantic Coastal Plain, the Stallings Island site, which was excavated by Cosgrove in 1929 (Claflin 1931) and the Thom’s Creek site (Phelps 1968) exhibit many cultural traits normally associated with Late Archaic shell mounds located in the interior. The stone tool assemblages recovered are typical of the Late Archaic, but the development of cooking tools was distinctly different between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain. At Stallings Island, located near the Fall Line, over 2500 steatite slabs and many steatite containers were recovered. It is theorized that the slabs were used as cooking stones (Sassaman et al. 1990:12). The distribution of recovered steatite is uneven in the Savannah River Valley and almost nonexistent at archeological sites located on the Coastal Plain. Pottery containers were also used at Stallings Island. The fiber-tempered plain pottery recovered at Stallings Island was dated at 1700 B.C. This is one of the earliest known uses of fiber-tempered pottery in North America (Stoltman 1966). Soon after the development of the Stallings Island fiber-tempered pottery, a similar sand-tempered pottery was developed along the South Carolina coast called Thom’s Creek. Both types developed similar decorative patterns of rows of punctations and pinches in geometric patterns (Phelps 1968; Sassaman 1993). Stallings Island fiber-tempered is the most common on the coast and in river valleys to the Fall Line in the Georgia-South Carolina area. The Savannah River Valley was at or near the center of the Stallings Island fiber-tempered pottery distribution with Thom’s Creek sand-tempered pottery being most common on the South Carolina Coastal Plain.

In 1979, Chester DePratter refined the lower Savannah River Valley ceramic sequence developed by Caldwell and Waring in 1939. The refinement was based on a reanalysis of the materials excavated by Caldwell and Waring in Chatham County during the Works Project Administration (WPA) era. DePratter prepared a second report published in 1991, which also contains the pottery descriptions from the 1979 synthesis. The earliest pottery described by DePratter is called St. Simons. Based on uncorrected radiocarbon dates, the St. Simons 1 ceramic series dates from 2200 B.C. to 1700 B.C. (DePratter 1991:8). The ceramics are described as fiber-tempered plain pottery usually formed as simple bowls with rounded to flattened bases (DePratter 1991:159). St. Simons 2 ceramic series dates from 1800 B.C. to 1700 B.C. and includes fiber-tempered plain, as well as punctated, incised and punctated and incised surface decorations.

The introduction and use Refuge I ceramic series temporally overlaps the period when the St. Simons ceramics were made and utilized at the mouth of the Savannah River. DePratter (1979) describes Refuge I ceramic assemblage as being sand and grit-tempered coiled ceramics, which were first encountered at the stratified Refuge site (DePratter 1976; Sassaman et al. 1990:12). The most common vessel shapes include conical jars or hemispherical bowls with conical, rounded, and tetrapodal bases. The surface treatments include plain, punctated, incised, and simple stamped designs (DePratter 1991:163).

Woodland (ca. 1000 B.C.- A.D. 1150)

The Woodland period is typically characterized as being a time when settlement patterns were expanded and technological innovations introduced during the preceding Archaic period were refined. The manufacture and wide spread use of ceramic vessels, mound building, and horticulture activities are among the most noteworthy manifestations of the Woodland period. The Woodland period can be subdivided into Early (1000 B.C. to 500 B.C); Middle (500 B.C. to A.D. 500); and Late (A.D. 500 to 1150) time periods.

Early Woodland 1000 B.C.- 500 B.C.

Until approximately 1000 B.C., settlements on the Georgia Coastal Plain consisted mainly of small inland sites located on well-drained soils and large sites along rivers and bays (Bense 1994:130). Soon afterward, however, the large shell middens and rings on the coast and floodplain were suddenly abandoned. Although the temperature and precipitation patterns of the Atlantic Coastal Plain resembled those of current weather patterns by approximately 800 B.C., the sea level suddenly dropped six to twelve feet which resulted in the degradation of the coastal and lower riverine habitats of that time. The sudden drop in sea level may explain why there was a noticeable shift in subsistence patterns recorded during this period on St. Simons Island from predominantly shellfish and fish to more reptiles and mammals (Marrinan 1975). The adaptive change in subsistence strategies necessitated by environmental change would logically require a change in settlement patterns as well.

During the Early Woodland period, St. Simons ceramics were gradually replaced by the Refuge II and III ceramic series. The vessel shapes remained generally the same as Refuge I series, but the incised and punctated decorative techniques were used less often. A new decorative technique called dentate stamped was introduced (DePratter 1991:166).

The small stemmed projectile point forms of the Late Archaic period continue to be used during the Early Woodland period. The raw materials used to form the stemmed and notched points recovered from the Savannah River area vary considerably as do the core designs. Evidence also exists that some Early Woodland period points from the area may be the result of retouching or recycling Late Archaic period points. These factors have led to difficulty in attempts to arrange the assemblages into typological order. The Early Woodland forms, however, when compared to Late Archaic forms are generally smaller, exhibit a wider range of haft element designs, are made on local raw materials, and are less frequently thermally-altered (Sassaman et al. 1990:161-162).

Middle Woodland (ca. 500 B.C.- A.D. 500)

During the Middle Woodland period, influences from the Hopewellian ceremonial complex and its associated burial practices spread from the Midwest into much of the Southeast. Hopewellian burial practices included the use of crypts or charnel structures to house the remains of the dead until they were buried in and under mounds. Most burial mounds were low domes with dimensions of approximately five feet in height and fifty feet in diameter at the base. Hopewellian ceremonial complex artifacts recovered in the Southeast include: earspools, mica cutouts, shell cups, greenstone celts, ornaments of shell and stone, and lumps of galena and ocher (Bense 1994:142). Although the Hopewellian influence dominated many areas of the Southeast, very little evidence of Hopewellian burial practices has been recovered along the Savannah River drainage (David Anderson, personal communication 1997).

A new type of mound, the rectangular-shaped platform mound, was also developed during the Middle Woodland period. Platform mounds were once thought to be manifestations belonging only to the Mississippian period, but mound excavations at sites like Pinson in Tennessee; Marksville in Louisiana; and Leake and Mandeville in Georgia have demonstrated the association of this mound type with the Middle Woodland period (Bense 1994:142).

During the Middle Woodland period, the stemmed bifaces that dominated the Early Woodland period were replaced by triangular points which have been variously referred to as Copena, Copena Triangular (Justice 1995), Candy Creek, and Greenville (Cambron and Hulse 1969). They have been recovered from sites in the Piedmont and Appalachian provinces with dates as early as 500 B.C. Oliver (1985) and Coe (1964) suggest that in North Carolina the introduction of triangular points accompanied the onset of pottery manufacture. Although, this is not the case on Georgia’s Coastal Plain where pottery was being manufactured and used prior to the introduction of triangular points. Evidence for the co-existence of stemmed bifaces and triangular points on the Coastal Plain suggest that when both components are present, stemmed bifaces vastly outnumber triangular forms. From this evidence alone, it is suggested that the triangular biface tradition was a late arrival in the Savannah area (Sassaman et al. 1990:161-162).

Although there is some temporal overlapping of Refuge III and Deptford I pottery at the beginning of the Middle Woodland period in the lower Savannah River drainage, toward the end of the Middle Woodland period the Deptford I series was predominant. Waring first identified Deptford ceramics in 1947, during the excavation of that site. The Deptford site is located on the south shore of the lower Savannah River, near Savannah, approximately fifteen miles east-northeast of Fort Pulaski National Monument. DePratter describes Deptford ceramics as being fine to medium quartz grit-tempered, coil manufactured vessels with straight to slightly flaring rims on cylindrical vessels with conical or occasionally rounded bases. The surface decorations associated with the Deptford I series pottery are cord marked, check stamped, and linear check stamped. Deptford I ceramics are dated from 400 B.C. to A.D. 300 (DePratter 1991:11).

Late Woodland (ca. A.D. 500-A.D. 1150)

It has been suggested that the Savannah River cultures of the Late Woodland period are an extension of the Middle Woodland period with a continuation of the cultural developments and technological advancements of the previous era (Trinkley 1990:21-22). However, the first evidence of intensive utilization of the floodplain settings appears during the Late Woodland. Along the upper Savannah River Valley, evidence of more intensive occupations is expressed in the form of pits, hearths, posts and scatters of shell (Anderson and Schuldenrein 1985:720).

Deptford series ceramics continued to be used well into the Late Woodland period with the addition of complicated stamped surface decoration. A rare and infrequently occurring pottery type was first identified as Oemler ceramics by Waring in 1930. Waring described the ceramics as a “floating complex”, which was thought to be related to the Deptford II series (Waring 1968:220). DePratter describes the Oemler ceramic assemblage as being fine sand-tempered, coil manufactured, complicated or check stamped cylindrical jars with straight to slightly flaring rims (DePratter 1991:174). Around 500 A.D., two new pottery types, Walthour and Wilmington, were introduced in the Savannah area (DePratter 1991:11). The pottery is described as being sherd or grog-tempered, coil manufactured, cylindrical vessels with round to slightly conical bases (DePratter 1991:174-176). The surface decorations found on the extremely rare Walthour ceramics included complicated and check-stamped designs, while the surface decorations associated with the frequently recovered Wilmington ceramics include plain, cord marked, fabric marked, and brushed patterns (DePratter 1991:177-180).

New small projectile points appearing in the Late Woodland period signal the invention of the bow and arrow sometime around A.D. 600. Jack’s Reef Pentagonal, Hamilton, and Madison points are known point types commonly recovered from Late Woodland sites in the Southeast (Justice 1995).

The Woodland to Mississippian transition in the Savannah River drainage is marked by a shift from small, widely dispersed sites to fewer, larger villages in or near floodplains (Anderson et al. 1986:45). By the time this settlement change was made (A.D. 1150), corn agriculture was clearly being practiced in the Savannah River Valley (Sassaman 1990:15).

Mississippian (ca. A.D. 1150 to contact)

The Mississippian period is commonly viewed as the period in which Native American cultures reached their greatest cultural complexity. This complexity is reflected in a hierarchy of site types ranging from single family habitations or “farmsteads” to multi-mound ceremonial centers, a stratified socio-political organization that has been broadly compared to chiefdom level societies, endemic warfare, specialization in the production of various traded commodities (shell, copper, and salt), and a heavy reliance on maize agriculture for subsistence (Anderson 1994; Bense 1994; Griffin 1967, 1985; Jennings 1974; Muller 1983; Pebbles and Kus 1977; Smith 1978, 1986). Earlier subsistence strategies such as hunting, fishing and gathering were used to supplement the agricultural crops. The Mississippian period has been subdivided into Early (A.D. 1150 to 1200), Middle (A.D. 1200 to 1400), and Late (A.D. 1400 to contact) time periods.

Mississippian cultures were intimately tied to the development of chiefdoms. Mississippian chiefdoms were organized on the basis of lineal descent through the female line, and are characterized by vast inequalities between persons and groups in the society. The chiefs were ranked above all others and members of his family were ranked according to their genealogical nearness to him. A complex set of cultural laws governing marriage rules, and customs, genealogical conceptions and etiquette in general combined to create and perpetuate this sociopolitical ordering. Continual attempts to expand the influence of the chiefdom and bring neighboring groups under economic and political control, increases in population, and preference for limited floodplain areas for farming led to regular armed conflict. Signs of warfare between chiefdoms is evidenced in the Savannah River Valley by the defensive fortifications documented at the Irene Mound site (Caldwell and McCann 1941:11). Based on research conducted by Larsen (1982) and more recent findings by Anderson (1994), fourteen Mississippian mound centers have been identified in the Savannah River basin (Anderson 1994:171; Larsen 1982).

The introduction and widespread use of shell as a tempering agent characterizes Mississippian ceramics in most of the Southeast. Not all areas adopted shell tempering, however, and this is especially true on the southeastern Coastal Plain. The term “Mississippian-like” has been used to describe areas of the Southeast that continued to use sand, grit, or grog tempered ceramics while adopting other manifestations of Mississippian tradition.

Early Mississippian (ca. A.D. 1150 to 1200)

The early Mississippian settlement pattern in the Savannah River Valley differed considerably from the earlier Woodland period. Large settlements with ceremonial centers surrounded by smaller settlements and scattered farmsteads were the most common site types during the Early Mississippian period. Ceremonial centers with various numbers of mounds functioned as the political and religious centers of the chiefdoms.

In 1928 and 1929, Antonio J. Waring excavated the Haven Home or Indian King’s Tomb which is located at the mouth of the Savannah River. The Early to Middle Mississippian burial mound excavated was circular and slightly conical in shape and measured roughly 2.4 meters in height and 23 meters in diameter. Two ceramic series, St. Catherines and Savannah, were recovered from the Haven Home site. St. Catherines ceramics are dated from A.D. 1000 to 1200. DePratter describes St. Catherines ceramics as being grog-tempered, coil manufactured, hemispherical bowls and deep cylindrical jars with rounded bases. The surface decorations include cord marked, net marked and burnished plain. Savannah I and II ceramics were also recovered from the site and appear to be associated with the second phase of mound construction. The only appreciable difference between St. Catherines and Savannah series ceramics is that Savannah uses sand rather than grog as the tempering agent. Savannah I ceramics have been dated from A.D. 1150 TO 1200 (Anderson 1994:171, 367).

Although in other areas of the Southeast maize agriculture is a key factor in defining Mississippian cultural traits, no evidence of maize has been recovered from the Early Mississippian sites excavated in the lower Savannah River Valley (Anderson 1994:318). This suggests that its role in the local Mississippian economy may not have been as great as in other contemporary societies in the Southeast.

Middle Mississippian (ca. A.D. 1200 to 1400)

The history of Southeastern archeology is marked by the excavation of a number of significant sites which have had a lasting effect on how the past is interpreted. The Irene Mound site is one of these milestone sites. Located on the south bank of the Savannah River just upstream of the city of Savannah, Caldwell and McCann began excavations there in 1937. The Irene mound complex consisted of two mounds, a rotunda or council house, and an associated fortified village that was occupied from approximately A.D. 1200 to 1450 (Caldwell and McCann 1941).

The largest mound measured approximately five meters high and forty nine meters in diameter at the base when it was excavated in 1937 (Anderson 1994:174-186). Eight construction episodes were identified at the large mound. The first three episodes were earth-embankment structures, and the next four were truncated pyramidal platform mounds. The ceramics recovered in the first seven episodes were Savannah I, II, and III, which date from A.D. 1150 to 1300. The last episode was a circular earthen mound with a rounded summit dated to the succeeding Irene I phase, A.D. 1300 to 1400 (DePratter 1991:11).

The smaller burial mound, located south of the large mound measured approximately sixty-one centimeters high and five and one half meters in diameter, also belongs to both Savannah I and II as well as the Irene I phase dated at A.D. 1324 to 1425 (DePratter 1991:11). The Irene rotunda or council house belongs to the Irene period and measures approximately thirty-six meters in diameter at the base.

The village area was fortified by a palisade wall. The earliest wall was constructed during the Savannah phase (A.D. 1200 to 1300) but was enlarged during the Irene phase before the entire complex was abandoned by approximately A.D. 1450 (Anderson 1994:174-186).

Savannah I and II phase ceramics are described as being sand or grit-tempered, coil manufactured, globular vessels with a short throat and a well-defined shoulder. The surface treatments include cord marked, burnished plain, and complicated stamped (DePratter 1991:183-188). The Irene ceramics consist of grit to gravel tempering, coil manufactured vessels. The most common vessel shape is a wide-mouthed bowl, but hemispherical bowls and elongate globular vessels with marked rim flare frequently occur. The surface treatments include plain, complicated stamped, incised and burnished plain (DePratter 1991:189-193).

Late Mississippian (ca. A.D. 1450 to contact)

During the Late Mississippian period, the Native American populations largely abandoned the area of the lower Savannah River Valley. Anderson (1994) concluded that the inability of the ruling elite to protect their subservient settlements plus the pressure of drought and harvest shortfalls eroded their political and economic support. Without sufficient protection or support from the ruling elite, the populace of the Savannah River Valley simply moved into the neighboring chiefdoms. This theory is supported by an increased number of Savannah River ceramics being recovered in the neighboring chiefdom of Ocute, which is located along the Oconee River (Anderson 1994:329).

The first recorded European contact with the Native Americans of the Southeast was in 1513 when Spain sent Ponce de L’eon to explore the region. Many subsequent attempts to colonize the south Atlantic Coastal Plain were made by Spain and France following initial contact. It is unlikely, however, that the first European explorers had direct contact with Native American populations in the lower Savannah River. Anderson’s (1990b) research has demonstrated that “the central and lower Savannah River basin was largely depopulated at the time of the De Soto entrada [1539]” (Anderson 1994:71).

The early Spanish settlers arriving to colonize America’s south Atlantic coast, known as La Florida, were often accompanied by Catholic priests who built small churches in the settlements for the benefit of the colonists. Priests of the Jesuit Order were among the first to reach the Atlantic Coast, but after numerous failed attempts to convert Native Americans to Catholicism and several massacres, they abandoned their efforts in 1572 and returned to Europe. The Franciscan missionaries, however, had achieved great success in Mexico and pressed the Spanish Crown for control of the new lands. Subsequently, Spain issued the Royal Orders for New Discoveries of 1573, which gave missionaries the central role in the exploration and pacification of the New World. Under the Royal Order, friars wages and expenses were paid by the Crown. In return, converted Native Americans were to become tax-paying citizens whose labor could be more easily exploited by the Crown than when they had been under the care of the friars (Weber 1992:94-96).

Franciscan missionaries soon began a new mission system along the north Florida and Georgia coast, which met with rebellion and destruction in 1597 by the native Guale Indians. The Franciscans once again established new missions along the north Florida and Georgia coasts. The northern leg of these mission extended into the Province of Orista, South Carolina. By 1660, the missions had been forced out of the Province of Orista to approximately twenty five miles south of the Savannah River. Mission Santa Catalina de Guale, located on St. Catherine’s Island, Georgia was then the largest (140 members) and the northern most of the missions (Weber 1992:101-103).

Located approximately thirty miles south of FOPU, Santa Catalina de Guale was built in 1604 and used until 1680. Archeological investigations by Thomas and Larsen beginning in 1987 found the mission church consisted of a rectangular-shaped wattle and daub building with a prepared clay floor, raised alter, sacristy and a peaked thatch roof (Thomas 1987).

The English colonization efforts along the Atlantic Coast were more intense than Spain’s. Between 1600 and 1700 over 500,000 English citizens crossed the Atlantic (Harris 1964). The English colonies depended on European material goods, and colonists readily traded imported items such as cloth, firearms, and West Indian rum in exchange for furs, deerskins and Indian slaves. The Native American’s desire for valued European goods prompted slave raids between neighboring aboriginal groups (Swanton 1946).

In 1715, the Yamassee War erupted and spread across South Carolina and the territory that would later be Georgia. By 1717, the colonists had battled back and caused a mass migration of Native Americans westward to the lower Chattahoochee River valley of Georgia and Alabama (Swanton 1979). From this point on, the history of eastern Georgia is one of European colonization, American Independence and the growth and conflicts of a new nation.

HISTORIC OVERVIEW

The history of Cockspur Island is rich and diverse. The island has served as the site of three military forts, lighthouses and beacons for navigating the Savannah River, a U. S. Quarantine Station, and a World War II Navy Base. It was briefly the capital of Provincial Georgia in 1776, when the Royal Governor took refuge there with the Great Seal of Georgia. The first Methodist sermon delivered in the New World was offered by Reverend John Wesley on Cockspur Island in the spring of 1736. In 1829, Robert E. Lee received his first military assignment at Fort Pulaski (NPS 1971:1).

Cockspur Island 1732 to Civil War

The original charter establishing the Province of Georgia as an independent trustee colony, under the British Crown, was awarded to General James Edward Oglethorpe in 1732. The east-west boundaries of the Province were from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean and the north-south boundaries were the Savannah and the Altamaha Rivers (DeVorsey 1970:63). Internal geographical boundaries were developed between the Native American Creeks or Muscogees, Cherokees and Choctaws and the European colonists. During the first month of Georgia’s existence, Oglethorpe met with a number of Lower Creek Indians led by the famous Yamacraw Chief Tomochichi. At the meeting between the Creeks and the Georgia colonists a “Treaty of Friendship and Commerce,” was signed. The treaty acknowledged Native American ownership of all lands “as high up as the tide flows” between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers and allowed the Europeans free right and title to the lands they occupied. The Creeks reserved the rights to use the barrier islands of Ossebaw, Sapelo and St. Catherines for hunting, bathing and fishing. They also reserved a tract of land to serve as the New Yamacraw village site at Pipe Makers Bluff, which was located upstream from the developing colonial city of Savannah. It was clearly understood by the Europeans that the boundaries served as limits to their development and expansion. The importance of this sentiment was demonstrated by the first law enacted in the Province by the Trustees for the Colony of Georgia on March 21, 1733, entitled An Act for Maintaining the Peace with the Indians in the Province of Georgia. Apparently, the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce was also respected and upheld, for in 1736, Oglethorpe mentioned that he was forced to give the Creeks large presents to obtain ownership to the Sea Islands other than Ossebaw, Sapelo and St. Catherines. Oglethorpe also mentioned that the Creeks had refused to allow Colonial settlements above tidewater on the Altamaha River (DeVorsey 1970:63-65).

During his governorship, Oglethorpe supervised the construction of the city of Savannah and its suburbs, the wharves, and a harbor lighthouse, which was located on Little Tybee Island. By 1752, Oglethorpe’s term had expired, and the once large Native American village of New Yamacraw located on Pipe Makers Bluff stood vacant (DeVorsey 1970:68).

Oglethorpe was not the only man with a pioneering spirit attempting to tame the new province. Reverend John Wesley gave the first Methodist sermon in the New World on the soils of Cockspur Island in 1736. Rev. Wesley and his brother, Charles, had traveled with other colonists from England aboard the Symond to the Province of Georgia. The group spent two weeks, February 5-19, on Cockspur Island recuperating from the journey (Wesley 1739).

In 1759, King George II granted ownership of approximately 150 acres at the western portion of Cockspur Island to Johnathan Bryan, Esquire. A small portion of the island, 4 to 20 acres, at the southeastern end was reserved by the Crown for public use (Lattimore 1961:6).

Spanish land holdings in La Florida were ceded to the Crown of England in 1763 after both countries signed the Treaty of Paris. The boundaries of Georgia were effected by the addition of new land holdings outlined in the treaty. The southern extent of the Colony was shifted south from the Altamaha to the St. Mary River and the Mississippi River now defined the western extent of the Colony.

In 1761, King George commissioned John Gerar William DeBrahm, later called William Gerard de Brahm, to survey the Province of Georgia and prepare a report for the Crown. The report was published in 1772. Well known for his expertise as a engineer as well as a cartographer, de Brahm was also employed to construct two fortifications. The first was a low sand embankment built around the perimeter of Savannah that had a reinforced talus of pine planks. de Brahm described the need for the fortifications in his report to the King in the passage that reads:

The City being open to South Carolina by the Communications which the Navigation of the Stream afforded, so that from that Province Supplies of Ammunition and Victuals might be had in time of Emergency; the Indians would never have it in their Power to do more Mischief than to burn the Houses in the Country, kill some Cattle and steal Horses; but the Colonists are able at any time to go out in Parties to attak and worst the Indians, and thereby would oblige the Remnant to return to their Country without having left them a single Chance of a Scalp buy sculking and surprising solitary Plantations, as they use to do, that every Colonist would be more ready to fight the Enemy when he knows that his Family and Property are safe and secure behind good Intremchment under the Auspice and Protection of the Governor, Council, Representatives, and all the Forces of the Province, surrounded with necessary Stores and Magazines; also be at Liberty to go or Send to Sea, or the Neighboring Province, from with Benefit they could dread no Probability to be cut off [de Brahm quoted in DeVorsey 1971:154]

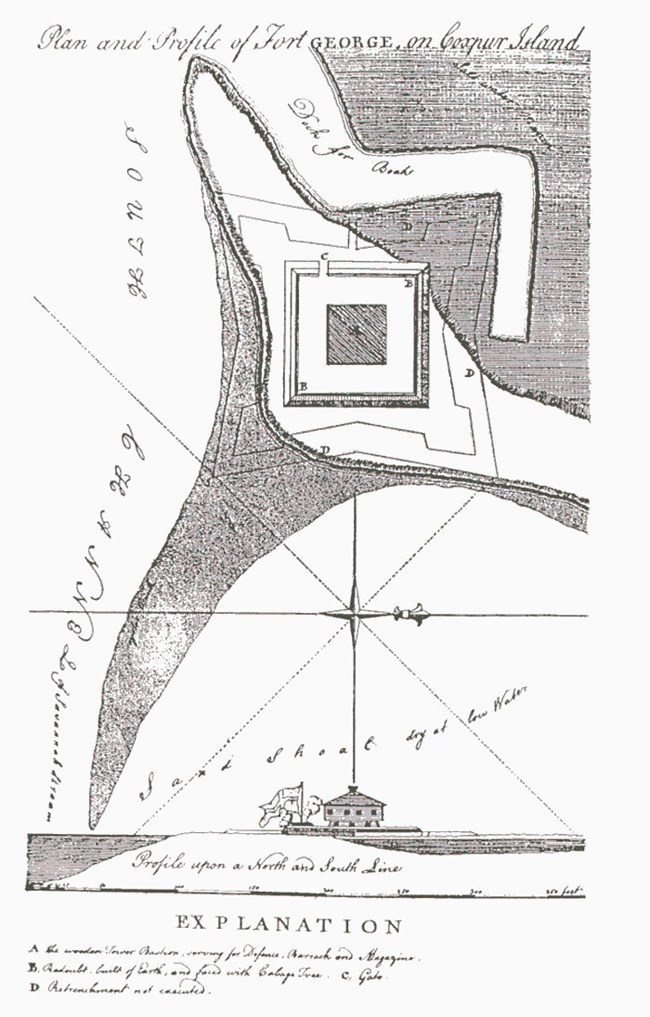

Fort George

The second fortification built by de Brahm in the Savannah River area was a small fort, named Fort George, in honor of the King of England (Cumming 1962:55). It was built at Cockspur Point, on the small plot of land, 4 to 20 acres, located on the southeastern portion of Cockspur Island which was reserved by the Crown for public use (Lattimore 1961:6) (Image 1). The fort was accompanied by a battery located on Tybee Island. de Brahm explained that the fortifications were more for stopping vessels in times of peace than for repelling hostile vessels. de Brahm laid out and supervised construction of Fort George in 1761. It consisted of a small redoubt, 100 feet square with a blockhouse, or wooden “tour bastionee” 40 feet square in the center. The blockhouse served as defense and barracks for the men, magazine, and storage house. The construction of the fort was funded by a tax levied against deerskins shipped from Savannah to Charleston by the Georgia Assembly (Coleman 1976:197). de Brahm apologized for the small size of the fort and explained that the Province of Georgia Legislature had allocated only 2,000 pounds sterling for the construction (de Brahm, cited in DeVorsey 1971:160).

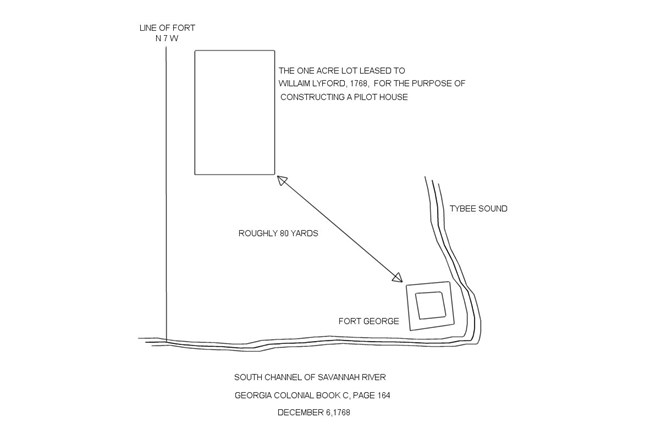

Savannah became an extremely busy seaport as the fledgling colony grew. The vessels entering the Savannah River often required a river pilot to help navigate the outer sandbars. The pilot of the river in 1768, William Lyford, requested permission to lease one acre of land on Cockspur Island to erect a pilot house. The pilot house was built diagonally from the north-west corner of Fort George at a distance of approximately 80 yards (Image 2). The lease was for 21 years unless Lyford ceased being the river pilot or he died. If either event occurred the pilot house and lease were to be transferred to the new pilot (Wallace 1924:186-187). The pilot house was burned by slaves during Lyford's term as river pilot in 1774 (Davis 1976:40).

By 1773, an account states that Fort George was almost in ruins. However, the fort was still manned by one officer and three enlisted men to issue signals to boats entering the Savannah River (Candler and Evans 1906:59-60). Shortly afterward, when revolutionary activities began, Fort George was dismantled and abandoned by the Patriots (Lattimore 1961:2).

In 1776, two British warships accompanied by a transport arrived at the mouth of the Savannah River, or Tybee Roads as it was sometimes called, to secure fresh provisions and information regarding the uprising in Georgia. Under the protection of the warship guns, Cockspur Island served as a haven for Loyalists fleeing from Savannah. Among the refugees was the Royal Governor, Sir James Wright, who escaped to the island on the night of February 11, 1776. He carried the Great Seal of the Province with him and thus briefly made Cockspur Island the capital of colonial Georgia.

The next month, the British ships sailed up the river to Savannah and engaged the Patriots in a brief battle and took provisions on board the vessels from the city. In 1778, the British returned and took control of the city. On October 8, 1779, patriots and allied French failed in their attempt to recapture Savannah in the Battle of Savannah. After the fall of Savannah in 1776, Cockspur Island was deserted and undisturbed. After independence was won, ownership of Cockspur Island automatically became the property of the State of Georgia by right of conquest (Lattimore 1961:2-3).

Fort Greene

In accord with the National Defense Policy established by President George Washington, a second fort was built on Cockspur Island. Fort Greene was built by the State of Georgia in 1794-1795 and named in honor of General Nathanael Greene. The fortification was constructed of timbers and earth that were enclosed behind pickets. The fort consisted of a battery designed for six guns, and a guardhouse constructed for the protection of the fifty man garrison (Lattimore 1961:3). It was located very near or at the same location as the previous fort, Fort George, on the southeast portion of Cockspur Island, along the South Channel of the Savannah River (Candler and Evans 1906:64). In 1804, nine years after the fort was constructed, a hurricane hit the coast of Georgia and huge waves swept over Cockspur Island. Several members of the garrison were drowned during the storm, and the fort was completely destroyed (Krakow 1975:82). For the next 25 years, Cockspur Island sat vacant, lacking any form of coastal defense.

Cockspur Island Lighthouse

The need for aids to coastal navigation along the Savannah River was addressed by erecting a beacon on Grass Island located at the tip of Cockspur Island. A congressional appropriation of $1,500 was allocated on May 16, 1826, to construct the beacon. Aids to navigation, at this time, were owned by the United States, administered by the Treasury Department, and overseen by the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury (NPS 1997a). A study of the harbor conducted by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1827, yields evidence of this early beacon (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 1827).

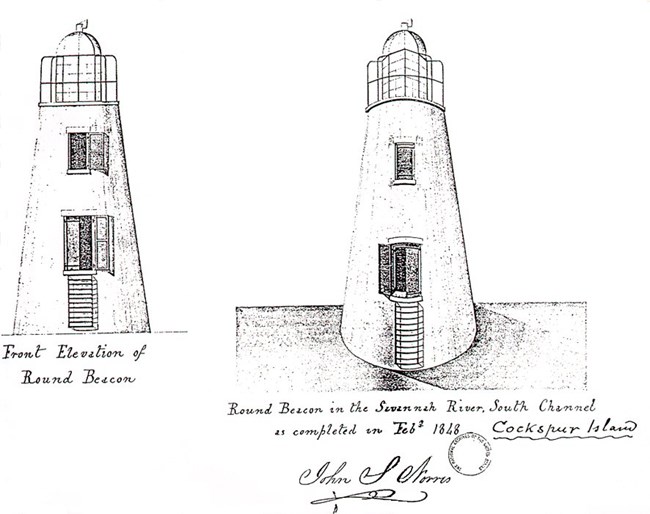

Early in the history of the Savannah area Cockspur Island was called “The Peeper”, because it was the first island seen as vessels entered the Savannah River (Urlsperger 1968). Its location made it the logical place for a navigational beacon. In 1834, a congressional appropriation of $4,000 was secured for the construction of the first bricked tower lighthouse on Cockspur Island. Congress made a re-appropriation of $3,000 in March 1837, allocated for the same construction. Construction actually began in 1837 and it was completed in 1839. A severe storm damaged the light in 1839, and in November of that year, Lieutenant Whiting, Engineer of the Sixth Lighthouse District for the Savannah area wrote a letter concerning rebuilding the damaged light (NPS 1997a). From 1848 to 1849, John S. Norris built a new Cockspur Island lighthouse and light keeper’s quarters on the southeast point of Cockspur Island (Lattimore 1961:2) (Image 3). Whale oil was used to illuminate the light, and approximately 90 gallons of fuel was used per year. The light was reportedly visible for nine and three quarters miles.

In 1856, the lighthouse was rebuilt and enlarged by the United States Lighthouse Service, and it is the same tower that stands today. The 46 feet tall conical lighthouse is constructed of brick and mortar. The base of the tower is 16 feet in diameter. A spiral brick staircase leads to the first landing, which is constructed of wood. A hatch and ladder provide access to the second floor where the lantern is mounted. A small iron door leads to an exterior catwalk encircled by an iron guardrail. During the reconstruction, a fourth order fresnel lens replaced the oil lamp (National Register of Historic Places 1972). The total cost of the tower and the keeper’s quarters was $2,670.

A second Lighthouse, located on what is known today as Oyster Bed Island was also constructed in 1856. The tower was constructed of brick and mortar but was square rather than conical. The two lighthouses were part of a system of lights to aid navigation of the Savannah Harbor known as the Jones Island System.

Fort Pulaski

During the War of 1812, British forces conducted a series of seaboard attacks that showed the weakness of the American coastal defense system. Consequently in 1815, President James Madison commissioned French military engineer, General Simon Bernard, to design an invincible system of defense for the Atlantic coast. Eighteen defensive works were listed for immediate construction, while 32 other projects were listed for future construction. The fortification to be constructed on Cockspur Island was designed by Bernard as a result of his commission and was to serve as a link in the coastal defensive system (NPS 1971:1). The Federal Government took control of the western portion of Cockspur Island on March 15, 1830, when it purchased the 150 acres that had been originally granted to Jonathan Bryan, Esquire in 1759 from the State of Georgia (Lattimore 1961:6).

President James Monroe, who succeeded Madison, took an active role in the completion of the coastal defense system. Cockspur Island was chosen as the site for the new fort in March 1821. The fort was a link in the Third System of United States Coastal Defense. Simon Bernard completed the design for Fort Pulaski in 1827. The design called for a massive two-story structure mounting three tiers of guns, but the deep mud of Cockspur Island was incapable of supporting the weight of such a heavy structure. Bernard’s revised design was approved in 1831. The revised design reduced the height of the fort to one-story and required the placement of wooden piling and grillage as foundation materials to support the brick masonry (Lattimore 1961:6-7).

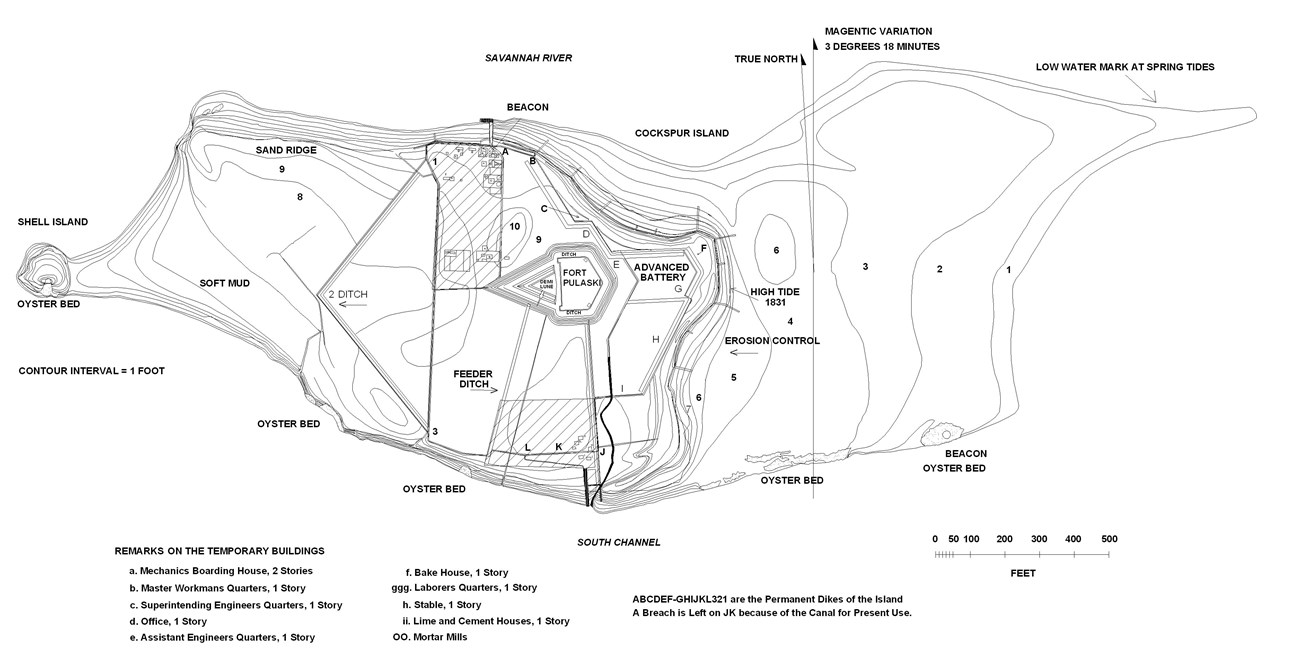

Major Samuel Babcock, of the Corps of Engineers, was placed in charge of building the fort in December 1828, although actual construction began in the early part of 1829. Robert E. Lee, a new graduate from West Point Military Academy, was assigned to duty under Babcock. This was Lee’s first military assignment, and Lee supervised construction because of Babcock’s ill health. Lee is credited with overseeing construction of the main drainage ditch, an earthen embankments or dikes that enclosed the acreage of the fort, the principal wharf or north pier, and temporary wood frame buildings to serve as work buildings and quarters. The system of dikes and ditches effectively drained and dried the muddy soils of Cockspur Island at the site of the new fort. Local weather often impeded the slow progress being made at the site. In the summer of 1830, a severe gale struck the Georgia coast, which damaged the dikes, swept away portions of the main ditch as well as the wharf. Lee rebuilt the dikes, cleaned the main ditch, repaired the wharf, and began excavating the foundation of the fort before he was transferred to Old Point Comfort, Virginia in 1831. Following Babcock’s death in 1831, Lt. Joseph K. F. Mansfield was assigned to Fort Pulaski. Mansfield’s tour of duty at Cockspur Island ended in 1845, but by then construction of the fort was nearly finished (Lattimore 1961:7) (Image 4).

On December 27, 1845, the State of Georgia transferred title to the small plot of land at the eastern end of Cockspur Island, the remaining 4 to 20 acres that had been reserved for public use by the Crown, to the Federal Government

(Lattimore 1961:6). The entire island was now under Federal control.

Completion of the fort had proved a difficult task for Mansfield; not only because the soils of Cockspur Island were of such poor quality that the fort had to be redesigned, but also from the immense size of the structure. The workmen consisted of military men assigned to duty at Fort Pulaski, skilled and unskilled laborers as well as enslaved Africans rented from local plantation owners. All were endangered by several infectious diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, typhoid and dysentery. Despite the hardships and obstacles, the fort was basically completed in 1847, after twenty one years of construction. The new fortification was named Fort Pulaski in honor of the fallen hero, Count Casmir Pulaski, who was killed at the battle of Savannah in 1779 and buried at sea near the mouth of the Savannah River (Lattimore 1961:7).

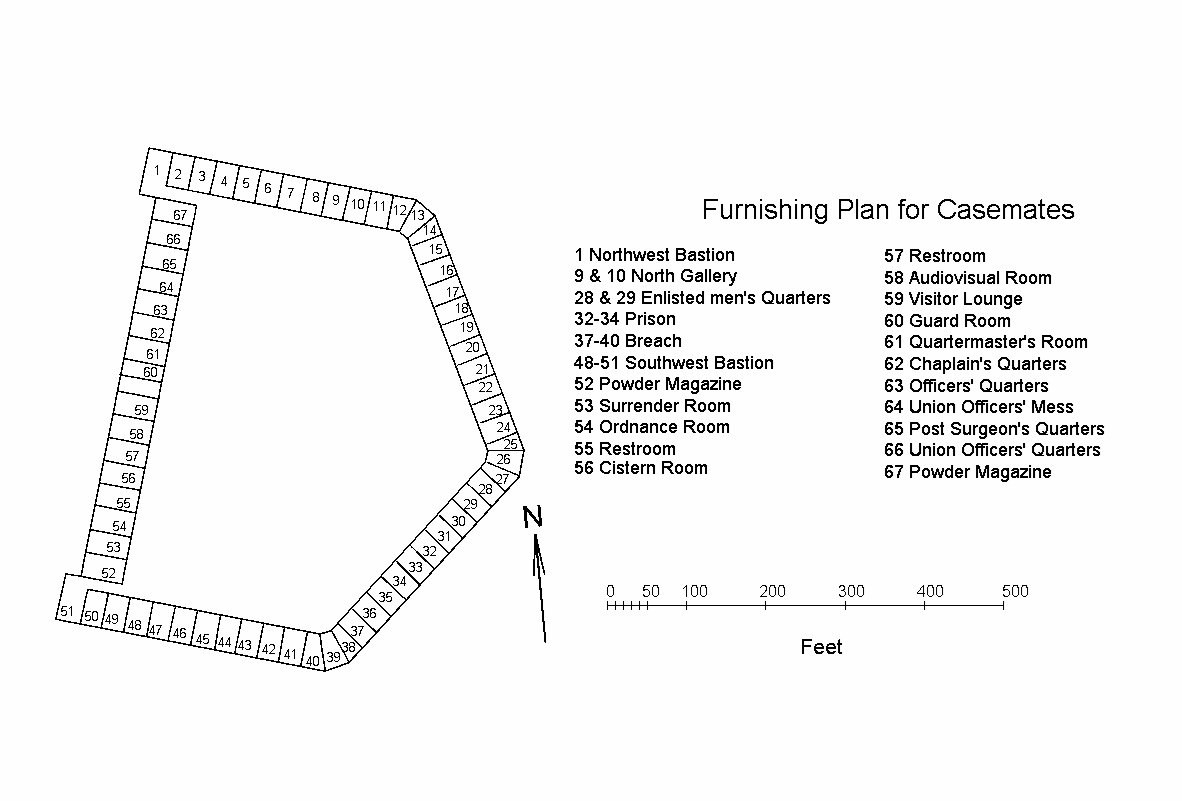

The completed fort is a five sided, one-story masonry structure and demilune enclosed by a wet moat. It covers approximately 9 acres and has a circumference of 1,580 feet. The total height of the fort is 32 feet (NPS 1971:2). The brick walls, ranging from 7 to 11 feet thick, form the casemates. The 67 casemates form the base of the terreplein and some casemates served as gun galleries while others provided housing for officers and enlisted men as well as storage for powder and ammunition (Image 5). The terreplein is approximately 30 feet wide. It is lined with lead and covered with sod to collect rainwater for the fort’s internal water system. Bricks brought to Cockspur Island came in lots of one to seven million at a time. It is estimated that as many as 25 million bricks were used during construction. The rose-brown bricks were manufactured at Hermitage Plantation two miles west of Savannah. The harder rose-red bricks used in the embrasures, arches and walls facing the parade ground were purchased from Baltimore, Maryland and Alexandria, Virginia. Granite and brown sandstone were quarried from New York and Connecticut, respectively (Lattimore 1961:6-7).

By the end of 1860 nearly one million dollars had been spent on Fort Pulaski. Originally the armament was to include 146 guns but prior to the Civil War only 20 guns were mounted, and the fort had not been garrisoned. The entire staff consisted of a caretaker and an ordnance sergeant (Lattimore 1961:7-10).

The volatile political situation in the United States prior to the Civil War prompted Georgia’s Governor Joseph E. Brown to prepare for the defense of the State. An appropriation of one million dollars was authorized on his recommendation to fund the formation of military troops and to purchase infantry and cavalry equipment. When the news of South Carolina’s secession from the Union on December 20, 1860, reached Savannah, the citizenry rejoiced. Meanwhile, Major Robert Anderson in command of the Union forces in the Charleston harbor secretly moved the garrison from the insecure position of Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island to Fort Sumter, which was a large secure fort in the middle of Charleston harbor. The citizens of Savannah were outraged by the move and feared that if no action were taken that Union forces would control all the major harbors of the south. Immediate plans were made to seize Fort Pulaski before Union forces could garrison the fort. On January 3, 1861, Colonel Lawton and fifty men each from the Savannah Volunteer Guards and the Oglethorpe Light Infantry, and thirty-four men from the Chatham Artillery took Fort Pulaski (Lattimore 1961:10-14).

Following construction, Fort Pulaski had been ill equipped and maintained by the Federal Government. Marsh grass grew over the site, the moat was full of mud and none of the twenty 32-pounder naval guns that had been mounted in 1840 by the Federal Government were functioning. Consequently, when Confederate Captain Francis S. Bartow took command of the fort, his compliment of men hurriedly worked to prepare the fort. Not only did the Georgia troops install two 12-pounder howitzers and four 6-pounder field guns, but the marsh grass was cut, the moat was cleaned and the 32-pound naval guns were repaired (Lattimore 1961:14-16).

By the summer of 1861, the Federal Government had devised a plan to recapture the seacoast fortifications. The three component strategy consisted of naval blockades at harbors held by the Confederates, a system of batteries built to bombard the forts, and a massive land invasion was initiated. On October 29, 1861 a convoy composed of 51 vessels left Hampton Roads to begin reclamation (Lattimore 1961:17-18).

Robert E. Lee, who was now commissioned as Brigadier General, was assigned as commanding officer of the Confederate forces of South Carolina, Georgia and East Florida. After the fall of Hilton Head and Bay Point, South Carolina in November 1861 to Union forces, the citizens of Savannah became concerned for their safety and those that could fled to the interior of the State. Lee ordered abandonment of the Sea Islands of Georgia and by November 10, 1861, Tybee Island was vacant. The Tybee Island batteries built by the Chatham Artillery were leveled, and the heavy guns were ferried across the South Channel of the Savannah River to Fort Pulaski. Two companies of the Tybee garrisons were transferred to the fort, and the remaining men were withdrawn to Savannah. Lee thought Fort Pulaski was safe even if the Union forces took Tybee Island, because the effective range of standard military smoothbore cannons was 700 yards. This is considerably less than one mile, which is the distance between Tybee Island and Fort Pulaski (Lattimore 1961:20-25). After inspecting the fort in November 1860, Lee made recommendations for the defense of the fort. Colonel Charles H. Olmstead, commander at Fort Pulaski supervised the alterations which included building traverses on the ramparts between the guns, digging ditches in the parade to catch shells, removing the light colonnade in front of the officers quarters, erecting heavy timber blindages in front of the casemate doors and covering them with several feet of soil (Young 1941:20).

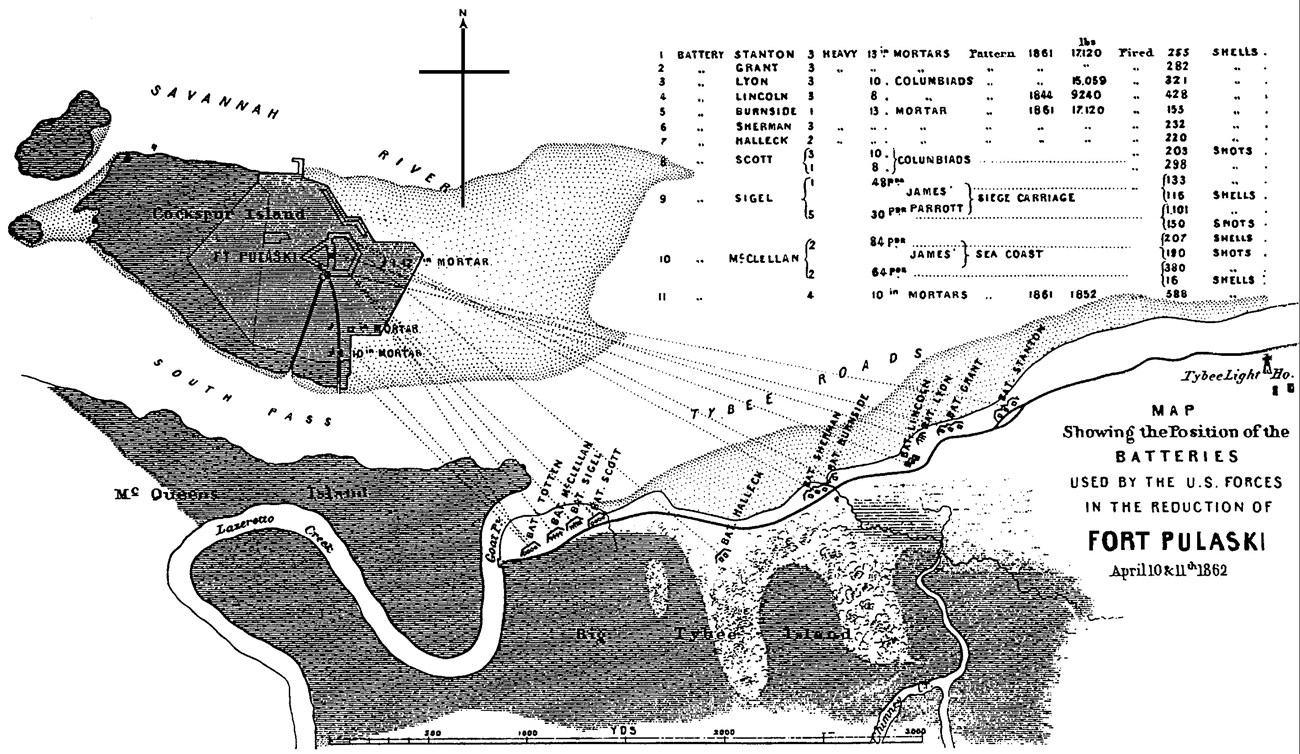

Part of the reclamation plan of the Federal forces included the installation of batteries on Tybee Island. Tybee Island is located one mile south-southeast of Fort Pulaski across the South Channel of the Savannah River, a perfect location for artillery attack on Fort Pulaski. Commanded by Captain Quincy A. Gillmore, Acting Brigadier General, Federal troops secretly installed eleven batteries along the northern shore of Tybee Island under the cloak of darkness in the early part of 1862. Materials and armaments including rifled cannons, the newest item in military technology, were unloaded at the eastern end of Tybee Island near the Tybee Lighthouse and transported overland to the installation sites. Hundreds of men moved the huge cannons and mortars with nothing but crude skids and sling-carts. They worked in hushed whispers and communicated with signal whistles for more than two months before the batteries were completed. Before dawn each morning the evidence of the night’s work was concealed by camouflage (Anderson 1995b:10; Gillmore 1988) (Image 6).

The Battle for Fort Pulaski

At 8:15 A.M on April 10,1862, the first Federal shots were fired from the right mortar of Tybee Island’s Battery Halleck. After thirty hours of nearly continuous bombardment, the fort was breached and the Confederate forces surrendered. During the battle, a flying brick fragment damaged the Confederate’s guard book. The fragment penetrated the book, punctured several pages and spilled ink so that many pages were soaked. The last Confederate entry in the guard book was written on April 11, 1862. It was penciled in and gives a first hand account of the battle from the perspective of a survivor.

Yesterday at 6 1\2 00 P.M. Hunter notified commandant to surrender the fort—he refused—at 8:00 A. M. Bombardment commenced—the first was heavy and without intermission until 7:00 P.M.—then firing ceased on both sides—the south face of ft. is badly breached—8 of our Guns disabled—8 men wounded none killed at 11:00 P. M.—The Federals opened fire and kept up during the night—at short intervals. Heavy firing renewed on both side this morning at seven 00—1100 A.M. the fort fast-giving away—Moulton of GW badly wounded—Armes of the OSS several wounded—The bombardment continued until 2 1\2 00 P.M.—Then surrendered [Entry was signed by Corporal Patrict Gurrey of the German Volunteers, Servent Jacob Fleck G.V. 1862].

Prior to April 11th, Fort Pulaski was considered invincible. The solid brick walls were backed with massive piers of masonry. All previous military experience had proven that the smoothbore guns and mortars in standard use at the time had little effect beyond 700 yards and past 1,000 yards had no chance at all of breaching a masonry fort. General Lee, himself, standing on the parapet of the fort with Colonel Olmstead, pointed to Tybee Island and remarked “Colonel, they will make it very warm for you with shell from that point but they cannot breach at that distance” (Young 1941:20). Union forces made it very warm indeed. Two hundred and twenty shots were fired from the 36 pieces on Tybee Island, which were placed at various distances from the fort. The southeast flank of the fort had given way and the ammunition magazine was in danger of exploding, forcing Colonel Olmstead to surrender. The terms of surrender were unconditional (Lattimore 1961:35).

The siege and reduction of Fort Pulaski surprised the military commanders of the south because the Bernard designed forts, which were thought to be impenetrable, proved to be no match for the new rifled cannons. The strategy that had guided military experts had to be revised to meet the threat of a new weapon of war. Fort Pulaski was now considered a relic of an age gone by (Lattimore 1961:36).

After the surrender, Federal troops occupied the fort and effected repairs to the damaged flank. Union troops, now in control of Fort Pulaski, commanded the entrance to the principal port of Georgia which effectively strangled the economic life of Savannah and the satellite communities (Lattimore 1961:35).

An article that appeared in the Savannah News Press after the battle stated that the Cockspur Lighthouse was in the direct line of fire during the reduction of Fort Pulaski, but the Lighthouse was not damaged. The angle necessary to send the projectiles the proper distance sent them over the top of the tower (Savannah News Press April 11, 1862).

The Immortal Six Hundred

Although the Civil War raged on, by 1863, the situation at Fort Pulaski was relatively quiet, and the Union garrison at Fort Pulaski had been reduced to a minimal holding force. In September 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman took Atlanta and prepared to march on Savannah. Ports all through the south were under pressure. In Charleston, South Carolina, Fort Sumter was held by Union forces under the command of General J. G. Foster. The city of Charleston was under the Confederate command of General Samuel Jones. General Jones agreed to quarter Federal prisoners of war from Andersonville Prison in Georgia to relieve the severe overcrowding at that facility. The prisoners brought to Charleston were placed at the Roper Hospital, the racecourse and the old jail (Joslyn 1996a:36). General Jones informed General Foster that Federal prisoners, 5 generals and 45 field officers, were being held within the city in hopes that General Foster would cease bombardment. According to principles agreed upon by the United States and Confederate States governments, prisoners were expected to be provided with safe quarters. General Jones had clearly breached this agreement. When General Foster received news of General Jones’ activity, his reaction was harsh and retaliatory. He immediately requested 55 Confederate officers of equal rank as those held in Charleston be transferred from Fort Delaware to Fort Sumter. When the Confederates arrived, they were quartered on the beach of Morris Island in front of the guns of Fort Sumter. A crude stockade was built of palmetto logs to contain them. The fifteen foot high stockade wall extended about nine feet into the ground to prevent prisoners from digging out. The entire enclosure was approximately one to one and one half acres in size. Tents were laid out in rows in the stockade to quarter the prisoners (Joslyn 1996a:38).

On August 3, 1864, Generals Jones and Foster exchanged officers. This should have put an end to the tactic of using prisoners as human shields, but on the same day, General Jones provided quarters in Charleston for 600 more Federal prisoners from Andersonville Prison. General Foster retaliated with a request for 600 more prisoners, all officers of the Confederacy, from Fort Delaware. There is some evidence that General Jones soon regretted the game he was playing. He repeatedly requested the removal of the prisoners, but without success. As General Sherman readied for his march across Georgia, the Confederates became concerned for the vulnerability of the prison at Andersonville. Consequently, General Jones received hundreds of new Federal prisoners daily. In late October fate intervened. Yellow fever became epidemic in Charleston and Jones was able to send the Union prisoners out of Charleston without the authority of his superiors. He sent the officers to Columbia, Georgia and the enlisted men to Florence, Georgia. When General Foster learned that General Jones had moved the Union prisoners, Foster sent the Confederate prisoners from Morris Island to Fort Pulaski (Lattimore 1961:38-40).

The Confederate prisoners or the “Immortal Six Hundred” as they later called themselves (Murray 1905), were suffering from the months of imprisonment at Morris Island when they arrived at Fort Pulaski. Their uniforms were in tatters, most were barefooted, and many were suffering from diarrhea and hacking coughs. Their numbers had been reduced from 600 to 520. Of the eighty missing, forty nine were hospitalized, four had escaped, two had been exchanged, two took the oath of allegiance with the Federal Government, six were in a convict prison on Hilton Head Island for attempted escape, thirteen were unaccounted for, and four were buried in the sands of Morris Island (Lattimore 1961:40).

The Federal commanding officer at Fort Pulaski, Colonel Philip P. Brown, promised the Confederate prisoners better treatment. However, requisitions to provide blankets, clothing and food were ignored; consequently neither blankets nor clothing were available. Food supplied to the Federal forces stationed at Fort Pulaski was not easily procured, but Colonel Brown split the garrison rations so the Immortal Six Hundred were fed. The supply of wood and coal was so low that only one cook fire per day was allowed. Colonel Brown was censured by his commanding General for his humane treatment of the prisoners. When Savannah surrendered to General Sherman in December of 1864, the prisoners were inspected by a Federal medical officer and put back on full rations. On March 5, 1865, the surviving prisoners, which numbered 465, were sent back to Fort Delaware (Lattimore 1961:40).

After the War

After the Civil War, General Gillmore, under the direction of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, modernized and strengthened Fort Pulaski. During 1869, and again in 1872, the demilune was remodeled with underground magazines, passageways, and emplacements for heavy guns. Several feet of soil was added to reinforce the underground fortifications. Major changes were also planned for the main fort, but after preparing the north end of the parade ground for huge concrete piers, the job was abandoned. On October 25, 1873, the last official record of the remaining garrison, the 1st U. S. Artillery, was penned. Meanwhile, proposals were under consideration for a new coastal artillery post on Tybee Island to replace Fort Pulaski (Lattimore 1961:42).

Fort Pulaski officially ceased being a military post in 1880. After that time, often the only inhabitants of Cockspur Island were the lighthouse keepers and their families, who were quartered in the casemates of Fort Pulaski. George W. Martus was the lighthouse keeper during the hurricane of 1881(Snow 1955:198). The island was completely covered by water during the storm. The water was reported to have been five feet deep inside the parade grounds. Twenty one years later, the U.S. House of Representatives responded to the hurricane threat by preparing an estimate of $4,000 to build a two-story lighthouse keeper’s house on top of the terreplein (U.S. House Document No. 231 Vol. 70. 57th Congress 1st Session, 1901-1902).

On June 27, 1884, the fort and the military reservation on which it stood, was turned over to the U.S. Engineer Corps. Around 1886, plans were made to establish a U. S. Quarantine Station at the western end of Cockspur Island. A revocable license was given on May 8, 1889, by the War Department to the City of Savannah to occupy and use a portion of the northwestern end of Cockspur Island for quarantine purposes (Young 1934:3). Construction of the United States Quarantine Station began in 1891. The West Indian Island type bungalow architectural style was used in constructing the raised one story frame buildings. The style was introduced to the area in the early1700s from Barbados, Guadeloupe, and other islands. The buildings were raised approximately 9 feet above ground surface on wooden pilings, which proved an effective measure against extreme high tides and storms as well as dampness, mosquitoes and gnats (Fort Pulaski National Monument 1952:8). The quarantine station adjoined the west boundary of what would later be National Monument property on Cockspur Island. The property, consisting of about 100 acres, was operated by the Public Health Service of the Treasury Department until March 1937, when the station was abandoned and entrusted to the National Park Service (Fort Pulaski National Monument 1952:8-9).