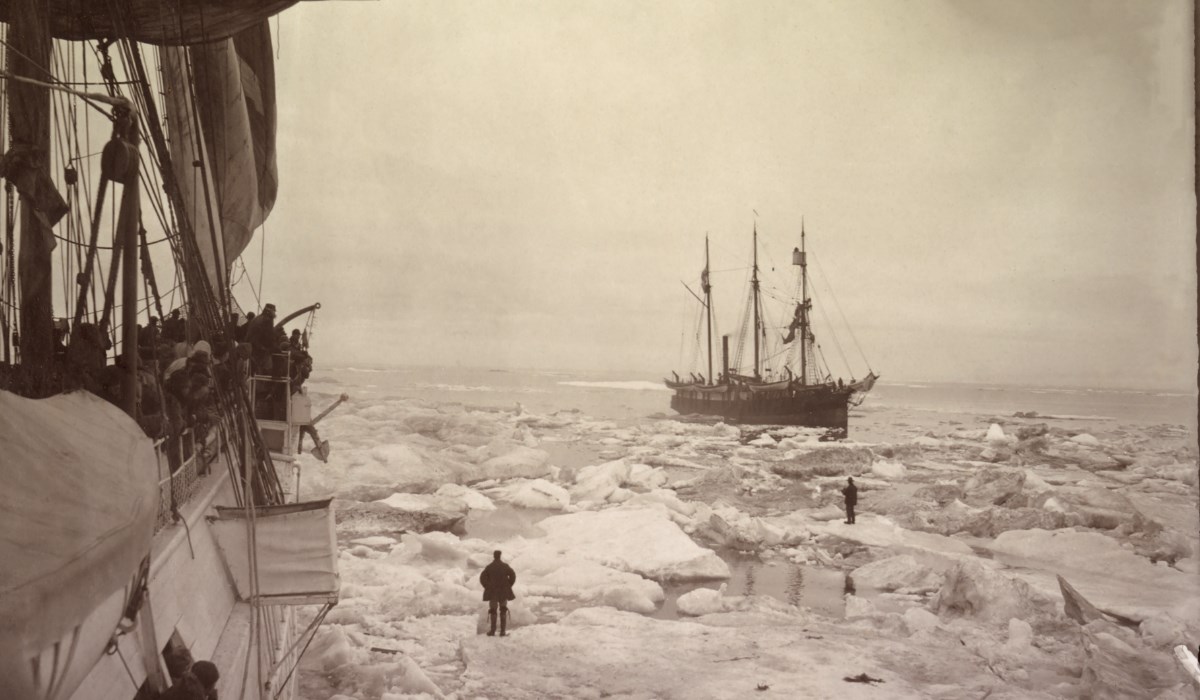

In September 1897, Actic ice closed in around the whaleships Orca, Jesse. H Freeman, Belvedere, Rosario, Newport, Navarch, Fearless, Jeanie, and Wanderer at Point Barrow, Alaska. The trapped ships only carried enough provisions to last them through January of 1898. In November, the United States Revenue Cutter Service (R.C.S.) — precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard — dispatched the cutter Bear on a daring relief mission to resupply the 275 stranded whalemen as quickly as possible. R.C.S. Captain Francis Tuttle, commander of the Bear, sailed as far north as he could. When it became clear that he could sail no further, he ordered 1st Lieutenant David H. Jarvis, R.C.S., ashore to command an overland relief expedition. The goal was to follow the frozen Alaskan coast, and bring food to the icebound whalers; 2nd Lieutenant Ellsworth P. Bertholf and Dr. Samuel J. Call joined Jarvis. Weather along the treacherous 1,500-mile journey was horrendous. Temperatures sank to 45 degrees below zero, making days when the mercury rose to 15 degrees below zero feel bearable.

Instead of sending a large group of the ship's crew on the relief expedition, Jarvis decided to hire natives that knew how to survive the difficult terrain. Their survival can be credited in part to the hospitality shown to Jarvis and his men by the many native peoples encountered along the way. Jarvis wrote: "It is so universal that it comes as a matter of course, and as a result does not seem to be properly recognized or appreciated. Often it is embarrassing, for the natives are so insistent and generous that it is hard to refuse to accept their offers.... Never in all our journey did we pass a house where the people did not extend a cordial welcome and urge us to go in.... What this means to a tired, cold, and hungry traveler can not be fully appreciated save by those who have experienced it, and my former good impressions of the Alaskan Eskimo were but intensified by this winter's journey. All that we ever gave in return for such hospitality, and all that was expected was a cup of tea and a cracker to the inmates of the house after we had finished our meal."

No one knew the condition of the stranded whalemen. Moving quickly was essential. The expedition pushed their dog teams hard and acquired new teams whenever prudent. Jarvis wrote in his diary: "The dogs which had brought us thus far had made with us a trip of 375 miles, and were completely worn out. They had been going constantly for twenty-one days with only one day's rest, and the hard, rough ice on the Yukon River and the crusty snow had worn their feet bare. Nothing short of a week's rest and good feeding would put them in condition to go on. I was loath to part with them, for they were the best dogs I saw in Alaska, but I could not wait for them to recuperate."

Reindeer, introduced to Alaska as a supplemental food source, were gathered from various herds along the expedition's path. Of the roughly 450 gathered, 133 came from Charlie Artistralock, a native Alaskan. He was hesitant to give up his source of livelihood. Jarvis explained that he had the authority to take the reindeer by force, but was happier to have the herd volunteered. Upon hearing this and the reason for the mission, Artistralock discussed the situation with his wife Mary. They determined that he would accompany the herd north as part of the relief effort. Missionary W. T. Lopp also offered his herd and services to Jarvis. The reindeer were critical, not only as a food supply, but as work animals pulling sleds packed with provisions. Starting a deer train was challenging. Everyone needed to be ready to move at the same time. "Just as the animals see the head team start, they were all off with a jump, and for a short time keep up a very high rate of speed. If one is not quick in jumping and holding on to his sled, he is likely either to lose his team or be dragged along the snow."

The relief expedition arrived at Point Barrow on March 29, 1898. Dr. Call quickly set to work attending the men, many of whom looked like ghosts, he later wrote. Jarvis allowed for additional rations and enforced standards of hygiene. Exercise was also imposed to give the idle men some physical activity. Shore whaling season soon arrived. Whalemen were eager to join the native hunting expeditions, but Jarvis forbid it. He believed that their desire to hunt with the natives was a ploy to get a share of their much-needed catch. He wrote: "The men could be of no use to the natives, and would only be a burden in the boats and make no end of confusion and trouble. The stranded whalemen were, however, allowed to go on their own hunts and returned with enough to supply their needs."

The Bear's arrival to Point Barrow in early July of 1898 led to thoughts of returning home among the stranded whalemen. Eager to depart, 97 of them boarded the Bear. Much to their disappointment, the ship was unable to sail south until mid-August. The Orca, Jesse H. Freeman, Rosario, and Navarch were lost, bu the mission to resupply the whalemen was a success. On January 17, 1899, President William McKinlye wrote in a message to Congress that the men who carried out th emission "reflect by their heroic and gallant struggles the highest credit upon themselves and the Government which they faithfully served. I commend this heroic crew to the grateful consideration of Congress and the American people." Jarvis, Bertholf, and Call were each rewarded Congressional Gold Medals to commemorate "their heroic struggles in aid of suffering fellow-men." Congress also approved $2,500 to be divided among Artistralock, Lopp, and the many native herders who "rendered material aid to the relief expedition." |

Last updated: August 30, 2018