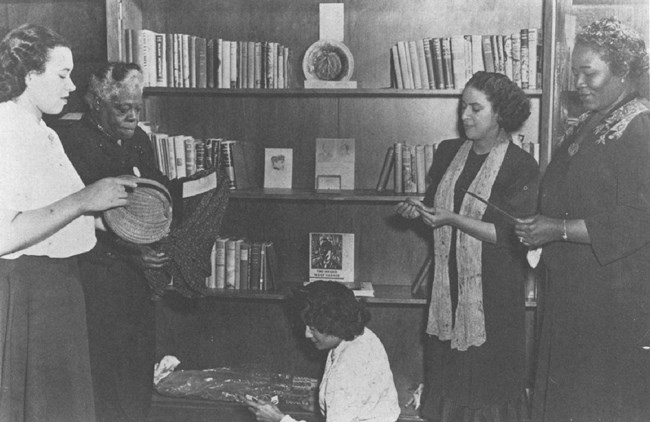

NPS / NABWH The first act of the Negro Women’s Committee was the establishment of an exhibit at the Washington, D.C. location of the WCWA. The 1939 exhibit consisted of materials on loan from the Howard University Library, where Porter served as the supervisor of what is now the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. Porter also worked hard to ensure that Black women were represented at the 1940 American Negro Exposition in Chicago. She made requests to many Black women around the country for materials that could be displayed in an exhibit on “Negro Women’s Archives”. During the Exposition, Thurman was responsible for traveling to Chicago and setting up the exhibit.4 While the dedication of this committee to the preservation of Black women’s history was apparent, it was not as successful as its later iterations would be. This can be credited to difficulty Porter faced in collecting materials for the Chicago exhibit from some of the women she contacted. After the Chicago Exposition, those who loaned materials for the exhibit were not willing to donate them to the WCWA. This can be attributed to the WCWA’s lack of inclusion of Black women in its organization.5 By 1941, the WCWA disbanded due to lack of funds.6 Despite this, the NCNW continued their preservation activities.

NPS / NABWH After a few years, the NCNW expanded their archives program. In 1944, Thurman was appointed chairwoman of the Archives Committee. In 1945, they hosted a series of programs called “Negro Women in History” to highlight the contributions of Black women through book reviews and exhibits.11 The popularity of these programs led the NCNW to declare a National Archives Day for June 30, 1946. The event was meant to “honor the memory and achievements of millions of Negro women of the past and to-day.”12 The NCNW proposed a series of events that were meant to bring local communities together in honoring the history of Black women and emphasize the importance of collecting that history. In January 1946, Thurman’s mother, Susie Ford Bailey, donated $1,000 to the NCNW for the purpose of establishing a “National Negro Women’s Museum.” Bailey’s donation enabled the NCNW to begin their National Archives Project, which aimed to establish the aforementioned museum, as well as to collect archival material and publish information related to those objects.13 To commemorate and promote the new Archives and Museum department, the NCNW created a radio presentation titled “On This We Stand.” This program, presented by Thurman and Lucy Schulte, highlighted the history of Phyllis Wheatley, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman.14

NPS / NABWH After Dorothy I. Height became president, the NCNW ushered in a new era in their preservation work. Under Height, the NCNW established the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial Museum and the National Archives for Black Women's History on November 11, 1979. In 1995, the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site became the 287th unit of the national park system. Until 2014, the National Archives for Black Women’s History, which is the only repository dedicated solely to Black Women’s History, was located in the carriage house behind the main building. Now, it is located at the Museum Resource Center in Landover, Maryland, but the commitment to the preservation of Black Women’s History remains the same. All of this would not be possible without the groundwork of the early Archives Committee of the NCNW. written by Sydney Coleman [1] National Council of Negro Women brochure, 1946, Henry P. Whitehead collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. [2] Bettye Collier-Thomas, “Towards Black Feminism: The Creation of the Bethune Museum-Archives,” in Women's Collections : Libraries, Archives, and Consciousness, ed. Suzanne Hildenbrand, (New York: Haworth Press, 1986), 44 [3] Correspondence from Dorothy Porter to Mrs. Emil Hurja, 11 January 1940, Box 1, Folder 1, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [4] Correspondence and Exposition Records, 1939-1940, Box 1, Folder 1, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [5] Collier-Thomas, “Towards Black Feminism”, 52-53 [6] Newspaper Article, “Women’s Archives Given to Colleges”, 24 November 1940, Box 1, Folder 1, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [7] Collier-Thomas, “Towards Black Feminism”, 52 [8] Report of the Archives Committee of the National Council of Negro Women, 17 October 1941, Box 1, Folder 1, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [9] Ibid. [10] Linda J. Henry, "Promoting Historical Consciousness: The Early Archives Committee of the National Council of Negro Women." Signs 7, no. 1 (1981), 255 [11] Collier-Thomas, “Towards Black Feminism”, 56 [12] NCNW Archives Project, 1946, 1946, Mary McLeod Bethune Papers, Bethune-Cookman College Archives, Daytona Beach, Florida [13] National Archives Project, 1946?, Box 4, Folder 2, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [14] On This We Stand radio script, 29 June 1946, Box 4, Folder 2, Series 5, SUBJECT FILES, 1936-1949, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Landover, Maryland [15] Collier-Thomas, “Towards Black Feminism”, 58; Dorothy I. Height, Open Wide the Freedom Gates : A Memoir. (New York: Public Affairs, 2003) 262 |

Last updated: September 28, 2024