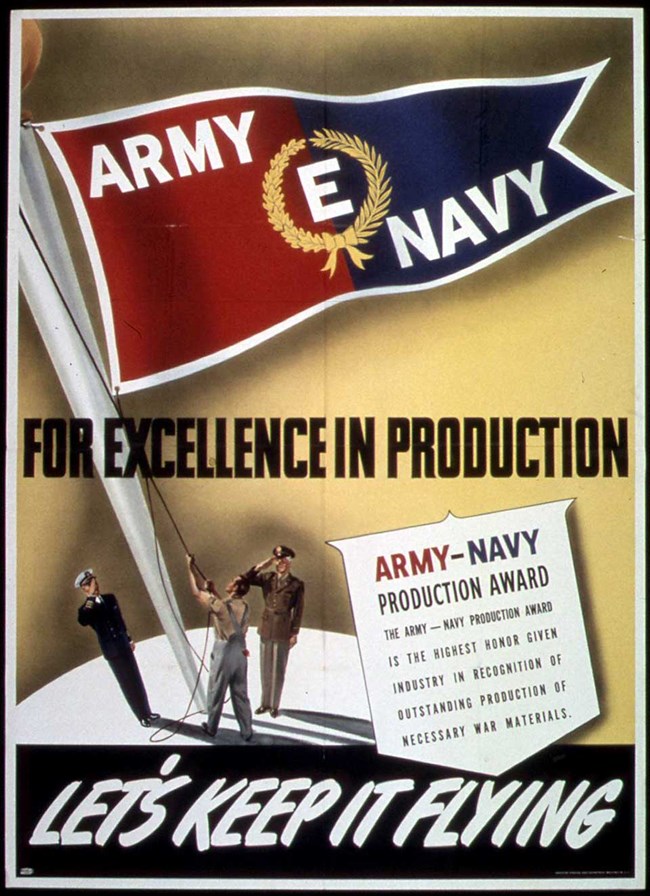

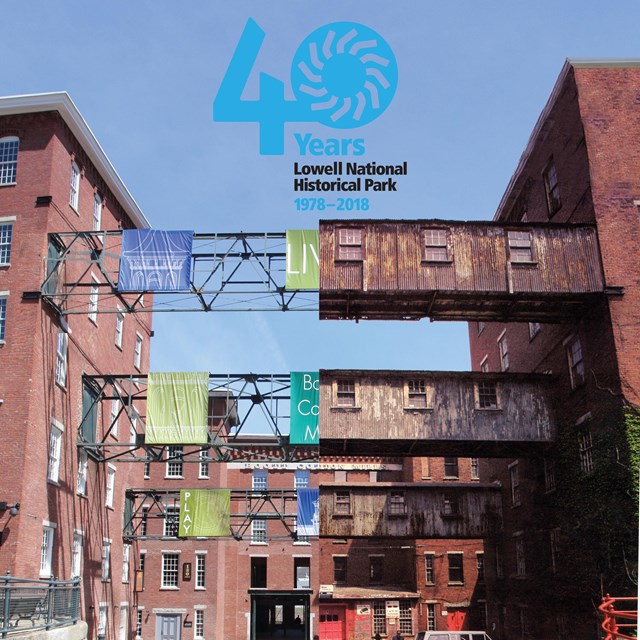

NPS In a few decades the population exploded from 300 to 30,000 residents. Newcomers, many of them immigrants, began to arrive in great numbers looking for work. For more than a century the identity and fortunes of the city that became Lowell were tied to the textile mills. Other industries, most notably patent medicine, came and went. All the while the textile mills dominated Lowell’s landscape and economy. The textile mills ebbed and flowed with the national economy. By the 1920s the mill economy was beginning to grind to a halt. A short-lived upswing during World War II was swiftly followed by a downturn for Lowell’s mills, and all of the original mills were out of business by 1958. Outdated technology, labor strife, and competition from other regions all led to the downward spiral of the mill corporations, and with them the economy, infrastructure, and morale of Lowell and its citizens. The 1960s brought urban renewal efforts to the struggling city. The sight of historic buildings being razed for new construction jarred many in Lowell. Forward-looking activists and city leaders fought to preserve Lowell’s heritage. The creation of Lowell National Historical Park in 1978 was a historic event in itself, showcasing the city’s industrial history and cultural heritage while spurring on the City of Lowell’s revitalization.

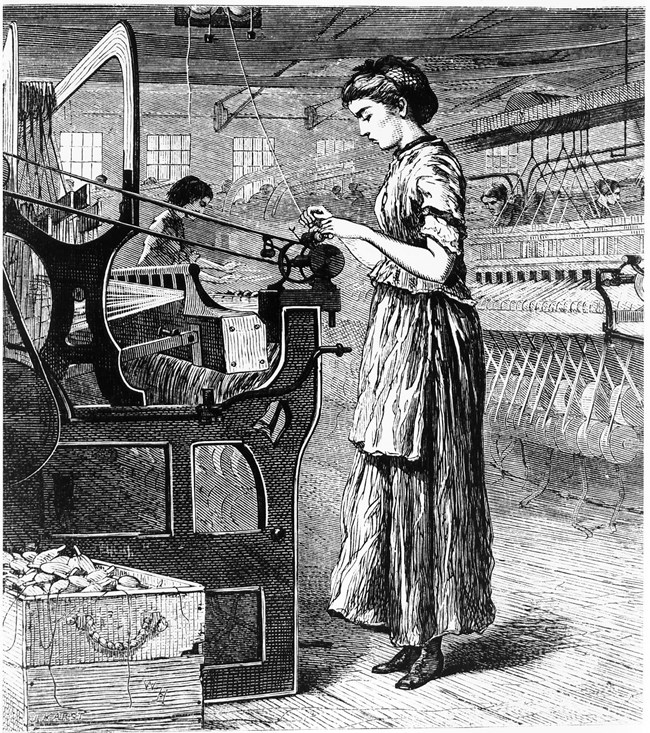

NPS Destination LowellWithin a decade of its founding, Lowell grew into a cosmopolitan city with a reputation and connections that reached around the world. Lowell was a destination for travelers interested in the novelty of the “mill girl” workforce; the visually arresting “Mile of Mills” along the Merrimack River; engineering marvels like the river wall and walkway. Visitors saw in Lowell a portent of the future of industry in America.

Made at Boott Cotton Mill. NPS Material ChangesAt first Lowell’s mills produced coarse cotton cloth. Marketplace competition pushed Lowell mills to produce finer and more specialized textiles. Towels were one of the Boott Mills most popular products. The handbill encourages customers to buy toweling by the bolt, with suggestions for how to make towels, aprons, and other items for the home.

Bain News Service

Lowell had seen “turn outs,” or strikes, since the 1830s. As corporations struggled to stay competitive, the divide between labor and management grew. Management used newer immigrants to fill lower-level jobs, intensifying labor tensions.

|

Last updated: August 16, 2019