Photo from the Grinnell Collection, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley Gold Found on the Kobuk! read a letter from prospector John Ross to the San Francisco Chronicle, claiming to have found $50,000 worth of gold on the Kobuk River. The year was 1898, and the gold rush at Klondike was beginning to wane. The rich goldfields at Nome were still a year away from being discovered, and disillusioned prospectors, tired of depleted claims in the Yukon and steep royalties levied by the Canadian government, were eager for an easier and less crowded score. Stories like Ross’s soon sparked the Kobuk River Stampede and a flood of would-be prospectors hoping to get lucky and strike it rich poured into what would later become Kobuk Valley National Park.

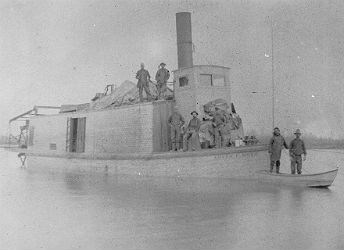

Photo courtesy of the Carrington Swete Collection Rumors of GoldDuring the spring of 1989, whispers of gold were everywhere. Stories of arctic rivers glistening with gold nuggets made news on both coasts. Captain Cogan of the whaling ship Alaska convinced 40 prospectors to buy passage to Kotzebue, Alaska with a fictitious story of a prospector who found $15,000 worth of gold in just two hours of panning on the Kobuk River, and the lure of the reputed riches on the Kobuk River attracted the interest of investors as well. The Kotzebue Commercial and Mining Company, founded in early 1898 before the claims of gold had been verified or any of the company members had set foot in the Kobuk Valley, raised a million dollars to fund mining operations in Arctic Alaska and purchased a steamer named the Agnes. E. Boyd, one of the largest boats to ever navigate the Kobuk River. During that heady spring, the rumors of gold and endless riches convinced some 2,000 would-be prospectors to make the trip to Kotzebue, Alaska with dreams of striking it rich in the remote Kobuk Valley.

Photo courtesy of the Carrington Swete Collection The Long WinterMore than half of the 2,000 prospectors that arrived in Kotzebue in July of 1898 turned back when local Friends’ missionaries and Inupiaq Eskimos swore that no gold had ever been found in Kobuk Valley, but the rumor of riches proved to be too strong a lure for some. Eight hundred men made their way up the Kobuk River and established thirty two camps where they waited out the long winter. During the cold, dark months, the men didn’t stray far from their camps. Little prospecting took place, and even less gold was actually found. Instead, the miners focused on recreational pursuits. Camps organized lecture series and discussion groups, and ice skating became so popular that extra skates were made from saw blades. Most of the prospectors, many of whom were from Southern California, survived the harsh winter, but others lost their supplies or their lives to the elements, the river and disease.

Photo courtesy of the Carrington Swete Collection A Lucky BreakWhen the ice thawed in the spring of 1899, the prospectors learned that gold had been discovered at Nome, and most of the men abandoned the Kobuk empty-handed. Proving how much of prospecting depended on luck, Erik O. Lindblom, one of the “Three Lucky Swedes” who discovered the first gold at Nome, had been a passenger on the Alaska’s voyage north to Kotzebue the previous spring. During a stop at Port Clarence, he learned that no gold had been found on the Kobuk River and abandoned the Alaska before it sailed through the Bering Straits. While his former shipmates wintered along the frozen Kobuk River, Lindblom found the first gold nuggets in what would become the Nome mining district and made a vast fortune in the ensuring gold rush. A Lasting LegacyTrace amounts of gold were eventually discovered on tributaries of the Kobuk River and small mining districts were established in the nearby Cosmos Hills and along the Squirrel River years later, but only small amounts of mineral were ever extracted. Perhaps a more lasting legacy of the Kobuk River Stampede was the large numbers of outsiders it brought to Northwest Alaska for the first time. The arrival of the miners had a profound impact on the native Inupiat, who had still been living the semi-nomadic subsistence lifestyle of their ancestors. The miners hired the Inupiat as guides and assistants, introducing them to western goods, tools and wage labor. Missionaries, teachers and trades followed in the miners’ wake and soon the Inupiat had settled into permanent villages, disrupting a millennia-old way of life. Real WealthThe Kobuk River Stampede also attracted the attention of the US Geological Survey. The failed gold booms along the Kobuk and other rivers in northern Alaska drew attention to the need for better maps and more knowledge of the terrain. A fleet of government scientists were dispatched to Alaska’s uncharted north to create maps and discover its economic potential, and USGS surveyors mapping the Brooks Range in the early 20th century were among the first to document the existence of Alaska’s black gold – oil. |

Last updated: July 20, 2020