Last updated: August 21, 2025

Article

Jean Lafitte: A Pirate's Life

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem MA

Who was Jean Lafitte?

Mystery and legend surround the life of Jean Lafitte. Was he a pirate, a patriot, or both? What became of the infamous smuggler? Even the date and place of his birth and death are unknown.

Lafitte was likely born in the early 1780s in either France or the French colony of St. Domingue, now Haiti. By 1810, he lived in Louisiana with his older brother Pierre. They might have been businessmen in New Orleans or independent privateers once. But undeniably, Lafitte was a smuggler known for his work in the Barataria wetlands.

/National Archives

Pirates, Smugglers, and Privateers

Lafitte always insisted that if he committed any crime, it was smuggling. He blamed American laws for forcing him into illegal activities. In 1807, the United States outlawed trade with Great Britain and France.

The U.S. plan was to remain neutral in the war against the French leader, Napoleon. This plan created other problems for U.S. merchants. With no imports from French or British merchants or colonies, U.S. merchants struggled. In New Orleans, traders began to run out of goods to sell.

Bans such as this created criminal opportunity. Smugglers were busy avoiding tariffs and taxes and finding rare or regulated goods. This benefited the sellers and buyers. Neither paid fees, taxes, or tariffs, lowering prices of imported or regulated goods.

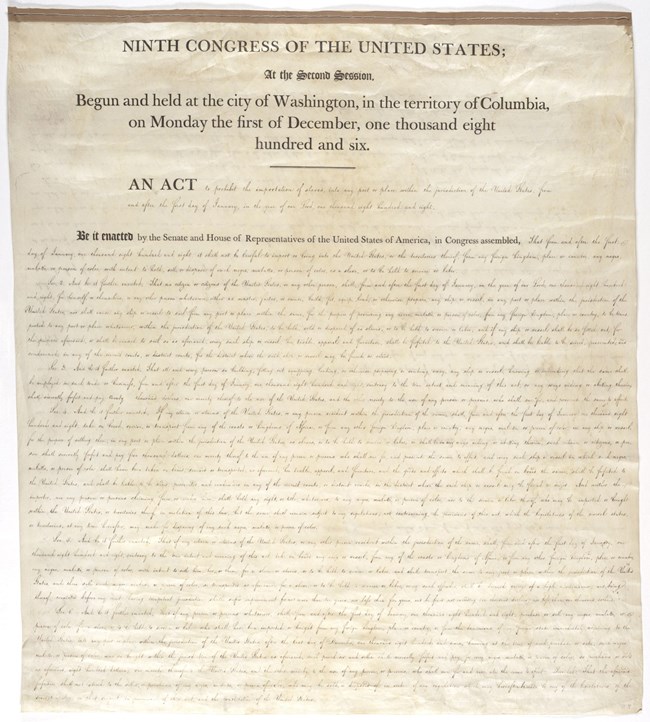

Not long after this in 1808, the U.S. passed the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves. This new law banned the U.S. from the international human slave trade. Enslavers could no longer source forced labor from Africa any more than they already had. This had many effects on the enslaved people of the United States.

Enslaved people born in the U.S. were considered less likely to seek freedom or "run away." Enslavers placed higher prices on these individuals because of this belief. Without the international trade, enslavers forced higher birthrates on enslaved women. This placed their lives at higher risk more often than ever before.

For Jean Lafitte, the 1808 prohibition created a business opportunity. Louisiana enslavers experienced a sharp rise in the cost of labor as American-born enslaved people became the only source of forced labor.

Lafitte used the ban in his favor in a step-by-step process in partnership with the infamous Jim Bowie and his brothers.

-

The Bowie brother would report Lafitte’s smuggled and trafficked goods to Louisiana officials. Louisiana law in the early 1800s gave informants half the value smuggled “contraband” or enslaved people brought to public auction.

-

Customs officials auctioned the enslaved people and contraband wares.

-

Before the auction, the Bowies would threaten other enslavers with violence. These threats kept any others from bidding in the auction. With no other bidders, prices for enslaved people stayed low at the auction.

-

Lafitte or the Bowies could then purchase the "contraband" back at a very low price. Then they would turn around and sell the individuals again for a much higher price.

Statue, Sculptor William M. McVey, 1936, Bronze, Texarkana, TX.

Photograph, Photographer Carol M. Highsmith, 2014, Library of Congress.

Lafitte and the Bowie brothers ensured both smuggling parties received a profit. If anyone knew the two allies were abusing the legal system this way, enslavers were eager to buy the enslaved people Lafitte trafficked into south Louisiana.

Lafitte also always insisted that he was a privateer, not a pirate. More of his operation was on land that at sea, and he was certainly more organized than some pirates. But it is clear Lafitte knew the law of the land and knew how to break it and exploit it for his profit.

A privateer also broke laws for profit. Unlike pirates, privateers had permission from the government to capture enemy ships.

But how did Lafitte argue for his privateer status?

The city of Cartagena in present-day Colombia had rebelled against Spain. The city gave "letters of marque" to multiple captains, including Jean Lafitte. This allowed privateers to capture Spanish ships and cargo. However, the United States did not formally recognize the government of Cartagena. U.S. officials also accused Lafitte’s men of attacking any ships they saw, not just Spanish. So, the U.S. government charged Lafitte and his crew with piracy.

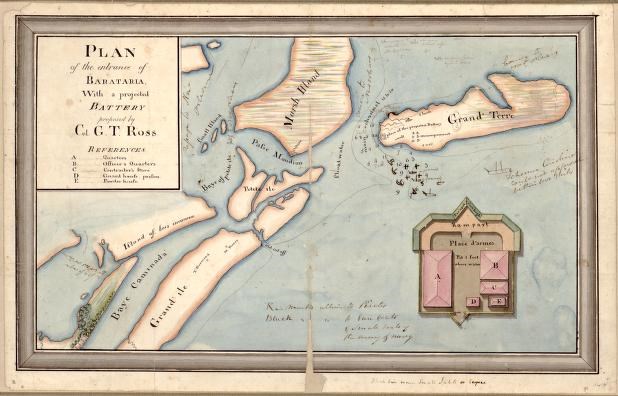

Map, G.T. Ross /Library of Congress

The Baratarians

The men working for Lafitte were called Baratarians. The name came from the waterways they used for smuggling. Today the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve is in this area.

Barataria’s swamps and bayous stretch south of New Orleans to the Gulf Coast. This area was famous for smuggling due to the deep-water harbor of Barataria Bay. The smuggling reputation grew and by 1810 the Baratarians established themselves in the region as a force to reckon with.

By 1812, Lafitte became the leader of the Baratarians. Their headquarters was on Grand Terre, a barrier island in the Gulf near Grand Isle. Lafitte may have had as many as 1000 people working for him. This force included free people of color and freedom seekers escaping enslavement.

Throughout Barataria, Lafitte built warehouses for goods and to hold enslaved people captive. Merchants, planters, and enslavers came to Barataria for auctions. Lafitte held his own auctions outside New Orleans to avoid the law. His knowledge of the swamps helped him to make quick getaways.

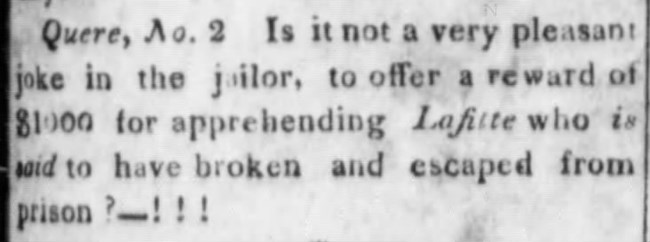

Several times customs officials and soldiers tried to capture Lafitte in the swamps, but they were usually captured, wounded, or killed first. In 1812, several Baratarians, including Lafitte and his brother Pierre, were captured but made bail and ran. In the summer of 1814, Pierre was arrested and jailed in New Orleans, but he escaped from jail under mysterious circumstances in September.

Brother, Businessman, Pirate, Patriot

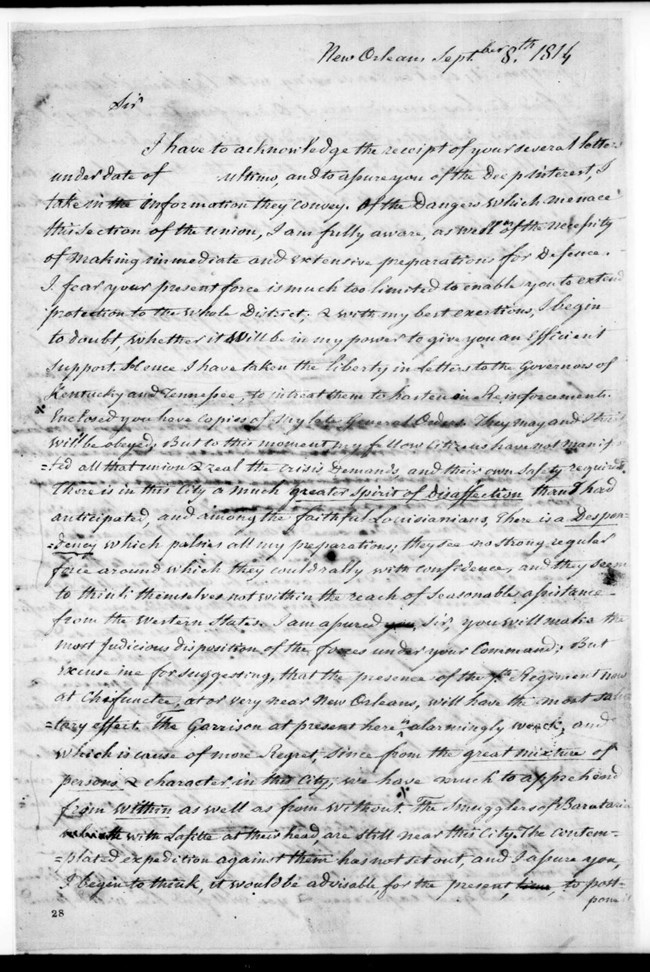

Britain and the United States declared war in June 1812. Until 1814, most of the fighting took place on the east coast or northern border of the United States.Jean Lafitte’s role in the War of 1812 undeniably influenced the outcome of the New Orleans campaign. The supplies, skills, and manpower of the Baratarians gave insight and advantage to the U.S. forces.

Why did Lafitte take such an active role in this military effort? Surely a wanted pirate had more to lose working with a government that wanted them arrested. Or so one might think.

Jean Lafitte and the Baratarians likely considered many points when deciding if they would join the battle. If they would join, then which side would they choose, the British or the U.S.? These questions required careful consideration.

/Library of Congress

/Maunsel White, 1783-1863, Cartographer.

/Library of Congress, Published in: Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical profile portrait in America / Ellen G. Miles. Washington, D.C. : National Portrait Gallery, 1994, no. 165.

One consideration might be the strength of the Royal British Navy. The "privateers" had been driven from bases in the British West Indies by this military force before. This history left the pirates with firm anti-British sentiments. This experience also taught that a government with a strong navy, like the British, would be bad for business.

Another reason not to ally with the British at the time, was Jean's brother Pierre Lafitte. The two brothers, close and well established in business together, both played roles in the New Orleans campaign. When the British spoke to Jean on Grande Terre Island in September, Pierre was in a U.S. prison.

Before the War of 1812, many in New Orleans condemned the pirates only passively. But in the summer 1814, Pierre and a few Baratarians were arrested in the streets of New Orleans. They were held without bail and indicted successfully.

Similar attempts made before had allowed the arrested parties to post bail and run away. So many profited from doing business with the pirates, few made real effort to stop the criminal activity. As the British threat loomed, local opinion shifted against the pirates.

Before summer's end, Pierre Lafitte was a convicted prisoner in the Cabildo of New Orleans. Pierre's prisoner status in the city may have motivated Jean Lafitte. Sending warning of the British plans to the U.S. forces might have aimed to buy favor for his brother's sake.

Lafitte was also cornered in his choice according to British records. When on the island, many Baratarians expressed anger at the arrival of the British. Some Baratarians wanted to arrest the British and send them to New Orleans for spying. When Lafitte had to leave the negotiations at one point, three men seized the British convoy and held them overnight in a confined building. Lafitte offered apologies for the treatment in the morning.

Lafitte requested two weeks to answer the British and deal with the agitators among his men. For Lafitte, this bought time and convinced the British to leave without inspiring an attack. The British, however, saw their poor reception and captivity to be the answer it was. They had no plans of returning to work with Lafitte or the Baratarians in the New Orleans campaign.

/Louisiana Gazette, September 6, 1814. /LSU Libraries

With tensions rising and U.S. military leaders planning to control the Barataria Bay, more trouble was on the way for Lafitte. September 16th, U.S. forces attacked Grand Terre, capturing pirates and vessels alike. The Laffites and a few Baratarians escaped the attack but were forced into hiding in the swamps. But the raid was successful in its goals, the bay was no longer open to the British or to pirates.

/Library of Congress

From the safety of the swamp, the Lafitte brothers pressed for a deal for themselves and the captured Baratarians. They offered aide to the U.S. during the coming conflict in exchange for pardons. Talking with state leaders, legislators, and Governor Claiborne, the Lafittes lobbied for months.

On December 17, 1814, Gov. Claiborne announced a pardon for Baratarians who volunteered their service. Pierre and Jean Lafitte, multiple Baratarian captains, and 300-400 others took the deal.

Historians have argued how much or how little Lafitte and the Baratarians influenced the Battle of New Orleans. Whether they made victory possible or not might never be fully agreed on. But the lives of Jean Lafitte, Pierre Lafitte, and the Baratarians reached far and wide.

Trade, local government, national history, myths and legends, arts and culture. The name Lafitte has touched so many different parts of south Louisiana and the U.S.

Without these histories, south Louisiana and the nation would not look the same today. From privateer to pirate, from businessman to brother, the history of Jean Lafitte evokes a myriad of feelings. Jean Lafitte in life and death has been praised and condemned for his actions. His actions caused great harm to some and great good for others. Neither part of Lafitte’s story can be true without the other. His impact was far reaching and long-lasting for people, nations, and legends. His is a history filled with the good and the bad, the bold and the resourceful. It is the history of a person whose life is as dynamic as the story of not only Louisiana, but also the nation.

What Happened to Jean Lafitte and the Baratarians?

After the war, President James Madison granted the promised pardons in February 1815. This created an interesting business opportunity for Lafitte and the Baratarians. With Presidential pardons, they were able to reclaim nearly half a million dollars in goods from the U.S. Navy.The ships and goods captured during the 1814 September attack on Grande Terre were meant to be prizes. The strategic victory of the Barataria Bay turned into a financial let down.

Many of the Baratarians settled in New Orleans or in the Barataria area. Some of their descendants still live there today. Lafitte later went back to smuggling on Galveston Island in Spanish Texas. His business there continued until he was kicked out by the U.S. Navy in 1820.

Jean Lafitte's exact whereabouts after that are unknown. His life and death remain as mysterious as any myth from the swamps and bayous of South Louisiana.

Myths and Mysteries

As the years passed, Lafitte became a legendary figure in south Louisiana. Are the stories true?

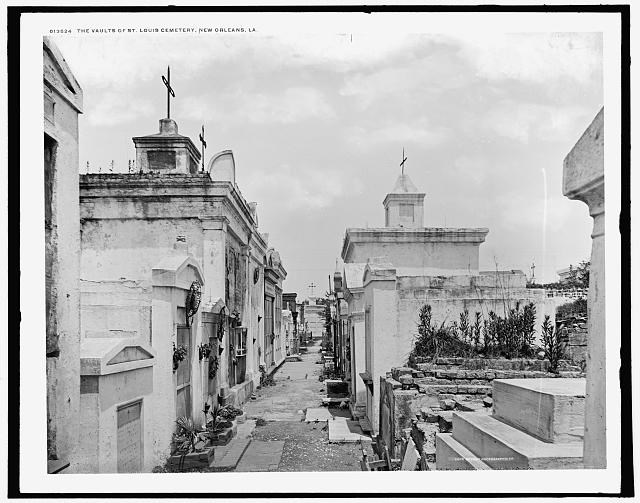

/LOC Highsmith, Carol M., 1946-, photographer.

Did the Lafitte brothers own a blacksmith shop in New Orleans’ French Quarter?

The story may have begun because Pierre Lafitte was often in the neighborhood. His long-time romantic partner, Marie Louise Villard, owned a building cross the street from today’s Blacksmith Shop. The building was on the northeast corner of St. Phillip and Bourbon Streets. It is likely that Pierre provided some of the money for Marie to buy the house from Claude Tremé on August 17, 1816.In New Orleans at that time, it was not unusual for a woman to own property in her own name. According to the 1795 New Orleans census, nearly 35% of houses were owned by women. Free women of color owned more than half of the women-owned buildings.

Villard was a free, multi-racial woman who moved a family of ten, into that property. This did not include enslaved people or the Lafitte brothers. Her free, multi-racial family had been in Louisiana since the 1760. For most of the years before the Civil War, about one-third of the New Orleans population was free people of color.

/Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection (Library of Congress)

We do know that she remained in that house at the corner of St. Philip and Bourbon Streets until Pierre Lafitte left New Orleans for good. When he did, he moved her and their children downriver to a house in the Faubourg Marigny neighborhood. She would live there until she passed away in the 1830s. Marie Louis Villard is buried in New Orleans’s St. Louis Cemetery No. 2.

Did Lafitte write a memoir?

In the 1950s, a man claimed to be a descendant of Lafitte and published “The Journal of Jean Laffite.” The journal was republished in the 1990s as “The Memoirs of Jean Laffite.” A major theme in the journal is Lafitte’s change of heart from enslaver to abolitionist.The self-claimed descendant also had documents claiming Lafitte lived until the 1850s. The documents also claimed the pirate was buried in Alton, Illinois. Historians doubt the authenticity of these claims.

/IMDb

Did Lafitte always respect the United States flag?

In the 1938 and 1958 films The Buccaneer, the character Jean Lafitte claims he never attacked an American ship. Outside of Hollywood, this is not true of Jean Lafitte's history.His men attacked several U.S. ships but apparently did not kill any crewmen. This might be because the targets did not fight back. Lafitte’s men did resist arrest by American forces, wounding, murdering, and capturing several in the encounters.

Is Lafitte buried in the town of Lafitte, Louisiana?

This story first appeared in a local newspaper in the 1920s from an unnamed source. There is no factual basis for this story. The story goes that the American Revolutionary War hero John Paul Jones was the uncle of Jean Lafitte and Napoleon Bonaparte. Claiming the pirate and emperor were cousins.After Napoleon’s exile to St. Helena by the English in 1815, Lafitte put a body double in his place. His cousin intended to smuggle Napoleon into the U.S., but Napoleon died on the trip. Then Lafitte supposedly buried Napoleon in the town of Lafitte’s Perrin Cemetery. Later, the story continues, John Paul Jones and Lafitte were also buried there.

Napoleon Bonaparte is buried in Paris and John Paul Jones, who died in 1792, is buried at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Lafitte’s final resting place remains unknown.

Why is a National Park named for Jean Lafitte?

In 1966, Louisiana authorized a state park to be established at the present site of the Barataria Preserve. The park was named after Lafitte because of the history of his smuggling operations in the region.In 1978, Congress created Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. This combined Chalmette National Historical Park (est. in 1938) with the Barataria state park and authorized a visitor center in the French Quarter. The park's mission is to preserve the natural, historical and cultural resources of Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta region.

- n.d. "An Act of March 2, 1807, 9th Congress, 2nd Session, 2 STAT 426, to Prohibit the Importation of Slaves." Accessed 2025. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/act-prohibit-importation-slaves.

- National Archives. 2022. The Slave Trade. January 7. Accessed 2025. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/slave-trade.html#toc-the-act-prohibiting-the-importation-of-slaves-1808.

- Brown, Everett S. 1925. "Letters From Louisiana, 1813-1814." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 11 (4): 570-579. Accessed 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1895914.

- Davis, Williams C. 2005. The Pirates Laffite: The Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf. Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- Frank, Dobie J. 1959. "Fabulous Frontiersman: Jim Bowie." Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 43-55. Accessed 2025. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4516292.

- Neidenbach, Elizabeth Clark. 2011. "Free People of Color." 64 Parishes, April 28. Accessed 2025. https://64parishes.org/entry/free-people-of-color.

- Owens, Deirdre Cooper. 2017. "Black Women’s Experiences In Slavery And Medicine." Chap. 2 in In Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, 42-72. University of Georgia Press. Accessed 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt69x.7.

- Sugden, John. 1979. "Jean Lafitte and the British Offer of 1814." Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 20 (2): 159-167. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4231887.

- Ulentin, Anne. 2007. "Free women of color and slaveholding in New Orleans, 1810-1830." Masters Thesis, LSU. Accessed 2025. https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3013/.

- Unknown. 1814. "Lafitte Escapes, $1000 Reward." Louisiana Gazette, September 6. Accessed 2025.

- Vogel, Robert C. 2000. "Jean Laffite, the Baratarians, and the Battle of New Orleans: A Reappraisal." Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 41 (3): 261-276. Accessed 2025. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4233673.