The following information is summarized from the Northern Colorado Plateau Network monitoring plan, published in 2004. Some details may have changed.

Park Legislative History

The establishment of Golden Spike National Historic Site followed a 20-year effort by local citizens who believed the spot where the transcontinental railroad was completed on May 10, 1869, had tremendous historical significance. The original site, which consisted of approximately three hectares (seven acres) around the Promontory town site, was designated a National Historic Site on April 2, 1957. However, initial designation was in nonfederal ownership. Thus, the site existed in name only and lacked a protected land base, staffing, and National Park Service (NPS) administration.

Subsequently, Public Law 89-102, signed into law July 30, 1965, set aside such lands as necessary "for the purpose of establishing a national historic site commemorating the completion of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States." This law provided for an authorized boundary, staffing, a development authorization, and oversight and management by the NPS. At this time, the historic site extended over 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) of original railroad grades and consisted of 892 hectares (2,203 acres).Following the completion of a general management plan for the Historic Site in 1978 (NPS 1978), boundaries were expanded by an Act of Congress on September 8, 1980. This public law expanded the boundary by 215 hectares (532 acres), though none of these additional lands have been acquired.

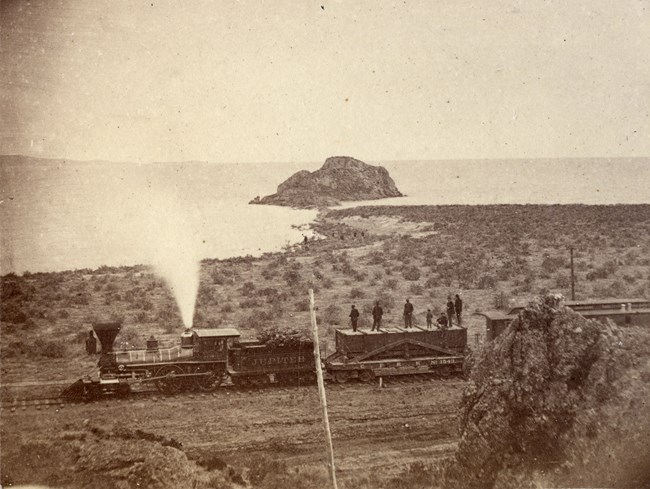

Left image

The Great Trestle near Promontory Summit, built by Union Pacific in 1869 and photographed by A. J. Russell. It stood for less than a year.

Credit: A. J. Russell photograph courtesy of Oakland Museum of California.

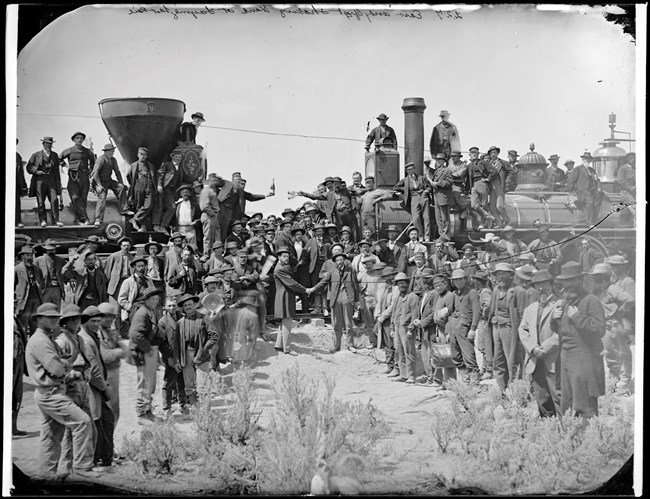

Right image

The former trestle site in 2020, where only the gravel grade and stone abutments remain in the landscape.

Credit: NPS

Park and Area Description

Presently, Golden Spike National Historic Site extends over 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) of original railroad grades and consists of 1,107 hectares (2,735 acres). Much of this acreage is contained within a 400-foot-wide right-of-way obtained from the Southern Pacific Railroad. Of the total acreage, 895 hectares (2,211 acres) are in federal ownership, and 212 hectares (525 acres) remain in private ownership. Annual visitation has ranged from 40,000 to 60.000 in recent years, with a spike in 2019 of over 100,000 visitors.The park can be divided into three major areas of historical interest: The Summit, the East Slope, and the West Slope.

NPS

The Summit

At Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, the final spike was driven to complete the nation's first transcontinental railroad. This is the point where the Central Pacific Railroad from Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, joined, making cross-country rail travel a reality. Only traces of these first railroad grades remain.

By May 1, 1869, anticipating the joining of the rails, the summit tent-village of Promontory was born. It subsequently survived as a small railroad-support town until 1942. Archeological investigation yielded many traces of Promontory's occupation and use. Sometime between 1916 and 1919, the Southern Pacific Railroad erected a monument in the area where the railroads first met. A plaque, added to the monument in 1958, indicates the area is a National Historic Site. After being moved on two occasions, this monument now stands just east of the visitor center.

The East Slope

Spectacular remains reflecting railroad building and maintenance stretch across the Promontory Range from its eastern base at Blue Creek to the summit. These consist of Union Pacific and Central Pacific parallel grades; parallel rock cuts, including the Union Pacific's "false cut" just west of the Big Trestle/Big Fill area; Union Pacific trestle footings; major Central Pacific earth fills; stone culverts; a number of former trestle locations; and two wooden trestles. The grades, cuts, fills, and trestle footings represent nearly every variety of the heavy work undertaken by the railroad workers except tunneling. Drill marks are visible in rock cuts, and borrow pits remain beside railroad grades.

The basal portions of telegraph poles march up the east slope of the promontories on the historic Union Pacific grade. Numerous stone foundations and rock walls, leveled tent platforms, remains of pit houses, dugouts and basements, fireplace chimneys, and hearth areas parallel the railroad grades on the east slope of the mountains. These indicate railroad construction worker camps, workshop areas (such as blacksmithing), and one of the "Hell-on-Wheels" towns associated with the final days of construction (Camp Deadfall).

The West Slope

From the summit area southwest, the parallel grades follow the gently sloping floor of Promontory Summit. This segment of the park includes a five-kilometer (3.2-mile) portion of the grade on which the Central Pacific laid its renowned "ten miles of track in one day" and those portions of the Union Pacific grade that were never completed or used. When the April 1869 order establishing Promontory Summit as the meeting point came, all Union Pacific work to the west stopped.

The incomplete rock cuts, partially built fills, uncovered culverts, and unfinished grade provide excellent examples of railroad construction processes, such as the stockpiling and reuse of size-graded stone material for grade foundation and the stair-step type of construction undertaken at the long rock cuts. Drill marks, stone culverts, and wooden box and stave culverts also occur along the west slope. Like the eastern slope of the mountains, the western slope contains spectacular evidence of construction worker campsites such as pit house remains, lean-to shelters, rock walls, trash pits, and rock chimneys perched against prominent limestone outcrops.

Location

Golden Spike National Historic Site is located in northern Utah, 52 kilometers (32 miles) west of Brigham City, 86 kilometers (55 miles) north of Ogden, and 145 kilometers (90 miles) north of Salt Lake City in Box Elder County.

Elevation

Elevations range from 1,329 meters (4,360 feet) to 1,609 meters (5,280 feet).

Size

1,107 hectares (2,735 acres)

NPS

General Description

Golden Spike National Historic Site contains hillsides, mountains, and plains at the summit of the Promontory Range in the northern basin of the Great Salt Lake and is in the Upper Sonoran Life Zone. The park lies in the northeastern reaches of the semi-arid Great Basin Desert.

The park lies between the North Promontory and the Promontory Mountains in the northern part of the Great Salt Lake basin. During glacial times, the summit was under ancient Lake Bonneville. As a result, old lake terraces form prominent features. Today's surface materials consist of fine-grained lake sediments and alluvial detritus. Subsurface deposits consist primarily of Pennsylvanian sandstone, shales, and limestones, and Tertiary extrusive materials. Numerous fault lines dating from the latter time run through the Promontory Range. Minor earth tremors (2.5–4.0 on the Richter scale) have been reported in the vicinity fairly often since 1965. No springs or travertine deposits occur, although such features are found at Rozel Point, 24 kilometers (15 miles) to the southwest of Promontory. Also at Rozel Point is an asphalt seep that was discovered before the first organized oil exploration in the early 1900s.

Annual precipitation averages 203–305 millimeters (8–12 inches), mostly as snow. Temperatures range from highs of 20°F in winter to an occasional 104°F in summer. July and August are the hot months, while the coldest weather is from late December through February. Winter nights are typically below 10°F. Spring and autumn months are generally mild but vary widely from day to day.

Snow depths vary considerably but average less than 305–356 millimeters (12–14 inches), with occasionally 152–203 millimeters (6–8 inches) falling per storm. Historical records for Promontory indicate that one snowfall in the late 1940s measured 94 centimeters (37 inches).Flash floods from occasional severe storms and spring runoff, aggravated by adjacent agricultural land use, cause erosion of historic grades, cuts, fills, and trestles. As a result, the Historic Grade and associated features have been damaged. Damage also occurs on a more gradual basis from natural erosion. Water erosion deterioration has been documented at Trestles 1 and 2. Water erosion has also impacted the east slope of the grade below a concrete box culvert west of these trestles. The loss of a segment of the Union Pacific grade two kilometers (1 mile) east of the visitor center was a serious preservation problem because of water erosion, but it seems to have been alleviated with the installation of water control gabions. Flooding between the visitor center and Kings Pass was a serious problem in 1983. Severe erosion occurred at the burned-out trestle, but this area has stabilized with the installation of water control gabions.Thunderstorms concentrate lightning strikes on the Promontory Mountains and salt flats near the west end, creating serious rangeland fire potential. Occasional prolonged, windy conditions in this semiarid rangeland hasten the weathering of facilities and equipment.

NPS

Plants and Animals

Visitors may encounter a wide range of native and nonnative plant and animal species throughout the site.

Flora

The region is semiarid to arid and is included in the shadscale–kangaroo rat–sagebrush biome of the northern Great Basin. The major flora consists of sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus spp.), broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), Indian ricegrass (Stipa hymenoides), and a variety of other grasses. A few Utah junipers and one historic boxelder tree grow on park lands. Non-native vegetation includes tumble mustard, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), crested wheatgrass (Agropyron desertorum), and other species.

Today’s vegetation is different from what existed at Promontory Summit 130 years ago. There is a much greater concentration of non-native species and noxious weeds. As a result, the vegetative landscape has changed in the park and on adjacent lands. However, the visual appearance of vegetative changes does not appear to have significantly altered the cultural landscape. The Passey onion (Allium passeyi) has been located on a rocky knoll on the east slope. It occurs only in Box Elder County and is a candidate species for future study and possible inclusion on the list of rare plants. There is no known plant or animal species listed as rare or endangered.

NPS

Fauna

Wildlife is varied and consists of larger mammals such as coyote, mule deer, bobcat, badger, and jackrabbit. There are also smaller mammals, reptiles, insects, and numerous bird species. Large numbers of raptors inhabit the area. Accipiters, falcons, buteos, and golden and bald eagles are particularly common during winter months.

Aquatic Features

Except for Blue Creek, which bisects the northeastern end, water is not available in stream or spring. The park receives water from a well (130 meters/427 feet deep) at the summit. Water is scarce in this semiarid region, which accounts for sparse population. The water scarcity has not affected operations at present visitation levels.

A. J. Russell, courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

Description of Cultural Resources

The park was administratively listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Additionally, in 1969, the historic railroad grade was designated as a National Civil Engineering Landmark. Cultural resources include historic structures, archeological resources, cultural landscapes, museum objects, and ethnographic resources. Several historic studies have been completed. More details are available in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network monitoring plan.

Interrelationship Between Management of Cultural and Natural Resources

Many resource management activities involve both cultural and natural resources:

- Management of the cultural landscape involves the cultural imprint on the natural landscape.

- A major objective of the fire management program is to reestablish natural vegetation regimens and reduce sagebrush, which covered less ground in 1869. Sagebrush is responsible for long-term degradation of cultural features. Aerial photographs from 1938 to the present also indicate vegetation changes.

- Preservation of grade resources is related to hydrologic runoff during storm events, effective erosion control, natural deterioration, and vegetation root systems.

- Many historic photographs show natural landscape features such as hillsides, mountain peaks, and vegetation, along with human-built features such as tracks, construction materials, trails, and structures.

- Location of archeological sites is highly related to geologic terrain.

Last updated: July 1, 2025