|

Summer 2022 Volume 22 Issue 1

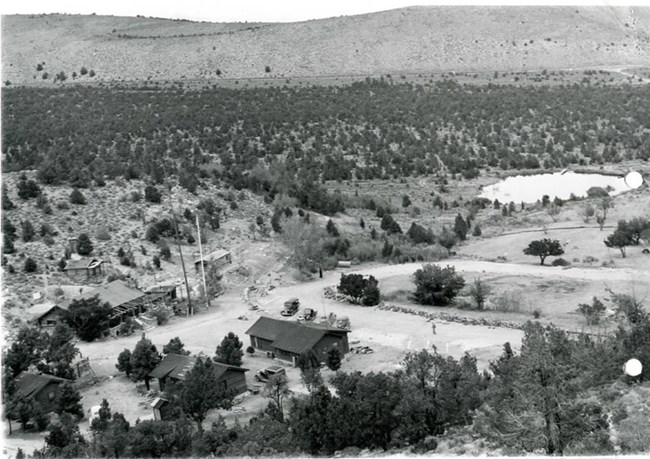

NPS Photo Thinning Project OutreachBy Julie Long, Supervisory Biological Science Technician and Bryan Hamilton, acting Integrated Resource Management Program ManagerIn October 2021, fire crews began work on the 65-acre Boundary Thin. This is one of several projects the park is working on to reduce fuels, protect life and property, and restore plants and animals. Based on questions and comments from the community and visitors, we wanted to provide more information on this project.

NPS Photo Why Should You Care? Tree removal is good for plants and animals. Pinyon and juniper trees compete with grass and sagebrush for water and sunlight. Without fires, trees crowd out sagebrush and grasses. Sage grouse depend on sagebrush habitat and are also declining due to tree encroachment. Tree removal projects like the Boundary Thin are used by biologists to restore native plants and animals, like sage grouse and pygmy rabbits. Historically, low intensity fires burned frequently, holding back tree encroachment, and favoring sagebrush and grasses. These fires, ignited by lightning or Native Americans, are sometimes called good fires. Tree removal is an important first step in reintroducing natural, good fires to the park. Let’s Keep the Conversation Going! If you have other questions, please contact Bryan Hamilton, acting Integrated Resource Management Program Manager email: e-mail us; phone: 775.234.7563 Additional Information https://www.sagestep.org/ ttps://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2018/1034/ofr20181034.pdf https://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/

Photo by Joey Danielson Results of 2021 Christmas Bird CountBy Gretchen Baker, EcologistIt was another year of dancing with ‘rona, but we managed to have an excellent turn out at the Snake Valley Christmas Bird Count on December 15, 2021 with 18 participants.This year we had the added challenge of a huge snowstorm the day before, which closed roads and made for difficult travel. Nonetheless, all the Ely and St. George participants showed up and helped with the effort. We even had enough people to duplicate parts of routes, which always yields more birds. The grand total was 55 species and 2538 birds seen on count day. Another 5 species were seen during count week. A couple standout bird species were 1) American Pipits—one team spotted 26 of them! They had only been counted on one count day and one count week previously and 2) a Snow Goose, previously a one-time count week bird, seen on a local pond north of the Great Basin Visitor Center, observed by another team. Every route (except one) had at least one species that was not seen on any other route. The most counted birds were mallards (211), pinyon jays (184), dark eyed juncos (184), European starling (158), and common raven (97). The Snake Valley Christmas Bird Count is an example of great volunteer involvement and interagency cooperation. Thanks to Utah Division of Natural Resources, Nevada Department of Wildlife, Ely Bureau of Land Management, Nevada Department of Conservation & Natural Resources, local volunteers, University of Nevada-Reno, and park staff for combining forces to get such good results.

Photo by Joey Danielson Bats in Spring ValleyBy Bryan Hamilton, acting Integrated Resource Management Program ManagerJoey Danielson, Kelsey Ekholm, and I recently had a paper published in the peer reviewed journal Population Ecology on Mexican free-tailed bats. These bats are one of the most abundant mammals on earth. They consume vast quantities of insects and provide $23 billion dollars annually in economic benefits to agriculture in the United States. A single colony in Texas was valued at over $3,000,000 in annual pest insect suppression services. But like many common species, Mexican free-tailed bats are often ignored by conservationists and biologists. A major emerging threat to Mexican free tailed bats is wind energy development.Millions of bats are killed worldwide by wind energy facilities each year. Migratory, high flying, open foraging bat species, such as Mexican free-tailed bats, are at high risk for wind turbine strikes and barotrauma. Two studies quantifying bat mortality at wind energy facilities near large roosts or in greater concentrations of this species found most fatalities (85% and 94%) were Mexican free-tailed bats (Miller, 2008; Piorkowski & O'Connell, 2010). Mitigating wind energy mortality requires data on biology of the affected populations. But often these data are not available, especially for common species like Mexican free-tailed bats. To address this, we collected data on Mexican free-tailed bats at a large roost in eastern Nevada. Two million bats use this roost. Did I mention the roost is 6 km from a 152-MW industrial wind energy facility? We used a harp trap to capture 46,353 Mexican free-tailed bats over 5 years. Although just over half of the bats were nonreproductive adult males (53.6%), 826 pregnant, 892 lactating, 10,101 post-lactating, and 4,327 nonreproductive adult females were captured. Juveniles comprised 11.5% of captures. Roost use by reproductive females and juvenile bats demonstrates this site is a maternity roost, with significant ecological and conservation value. To our knowledge, no other industrial scale wind energy facilities exist in such proximity to a heavily used bat roost in North America. Given the susceptibility of Mexican free-tailed bats to wind turbine mortality and the proximity of this roost to a wind energy facility, we need to continue work at this site. We need more information on bat mortality and the effects of mitigation. Pattern energy has been an excellent partner and works hard to protect bats at their facility. I hope we can publish the results of this work soon. Surprisingly, we have almost no information on migration patterns of Mexican free-tailed bats in the southwest and California in particular. We hope to use the MOTUS network to understand these migration patterns. This information would allow much more precise siting of wind energy facilities and help with local mortality mitigation. Read the paper here: https://esj-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/1438-390X.12119

NPS photo Gretchen Baker Lint Camp RecapBy Gretchen Baker, EcologistWho likes spring cleaning? Fifteen volunteers came from Baker, Ely, Reno, Salt Lake City and the Wasatch Front, Bend, Oregon and southern California to spend two days helping restore Lehman Caves during the annual lint camp on March 2 & 3, 2022. About half of the attendees were returning lint camp pickers, while the remaining half were new. In addition, about half were cavers from grottos, while the other half were general public. Final Thoughts As a thank you to attendees, we showed the National Geographic movie The Rescue about the 2018 Thai Cave rescue and also did a tour through the Talus Room and West Room. Many attendees say they don’t need a thank you, just knowing that they are helping make the cave a better place is thanks enough. We are so lucky to have such dedicated volunteers! We suspect that we’ll be able to continue to fill lint camps quickly, especially if we adopt what one participant suggested as the new lint camp motto, “You missed a spot.”

NPS photo Mountain Lions are Keystone SpeciesBy Bryan Hamilton, acting Integrated Resource Management Program ManagerMountain lions are keystone species. Through interactions with their prey, mountain lions create “top down” effects that regulate prey abundance and behavior, reduce herbivory, invasive species, and disease transmission, while increasing soil fertility and biodiversity (Beschta and Ripple, 2009). These predator induced trophic cascades can restore and maintain healthy ecosystems (Fraser et al., 2015).However, predator management is a polarizing issue. Despite the positive effects of predators on ecosystems, mountain lions can be viewed unfavorably, particularly in rural areas. Further complicating predator management is the rural urban divide. Mountain lion conservation is widely supported in cities and suburbs, but mountain lion habitat is mostly in rural areas on federally managed lands in Nevada. Rural communities that co-exist directly with mountain lions often hold fundamentally different views on wildlife management and unlike urban dwellers, may not support predator conservation (Manfredo et al., 2021). National Parks find themselves in the middle of this controversy. The mission of Great Basin National Park is to protect its resources and ecosystem processes “unimpaired for future generations”. Apex predators are valued as an integral component of the faunal community but most national parks are not large enough to protect intact predator populations. Large-bodied obligate carnivores like mountain lions must leave the sanctuary of parks, where conflicts between lions may arise. Cooperative conservation is the only effective management strategy for large animals, like mountain lions, which must be managed at landscape scales, across administrative boundaries (Elbroch, 2020). Cooperative conservation recognizes that wildlife management is a human endeavor. Without community support, dialogue, and engagement, conservation falls flat and difficult problems become more difficult. Despite this reality, most agencies and conservation biologists fail to acknowledge the importance of social differences and human behavior in managing predators. To improve mountain lion management, Great Basin National Park has applied for Southern Nevada Land Management Act funding to implement the cooperative conservation model. This project will use mountain lion research and management as tools for outreach and community engagement. Mountain lions will be captured and fitted with satellite linked GPS collars. When the GPS locations become tightly clustered, this often means the lion is feeding on prey. After the lion leaves the kill, citizen scientists and school groups will investigate those kills and collect information about patterns of mountain lion predation. The project will also hold regular meetings in Baker and Ely, connect students from urban areas with landowners and livestock producers around the park, and provide training in wildlife techniques. Using these data, scientists can determine the home ranges, abundance, diet, and habitat use of mountain lions. Ultimately this project will improve predator management, ecosystem health, and human well-being through mountain lion research and community engagement. References: Beschta, R. L., and W. J. Ripple. 2009. Large predators and trophic cascades in terrestrial ecosystems of the western United States. Biological Conservation. 142:2401-2414. Elbroch, M. 2020. The Cougar Conundrum: Sharing the World with a Successful Predator. Island Press, Washington.Fraser, L. H., W. L. Harrower, H. W. Garris, S. Davidson, P. D. N. Hebert, R. Howie, A. Moody, D. Polster, O. J. Schmitz, A. R. E. Sinclair, B. M. Starzomski, T. P. Sullivan, R. Turkington, and D. Wilson. 2015. A call for applying trophic structure in ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology. 23:503-507. Manfredo, M. J., R. E. Berl, T. L. Teel, and J. T. Bruskotter. 2021. Bringing social values to wildlife conservation decisions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 19:355-362. Rominger, E. M., H. A. Whitlaw, D. L. Weybright, W. C. Dunn, and W. B. Ballard. 2004. The Influence of Mountain Lion Predation on Bighorn Sheep Translocations. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 68:993-999.

NPS photo Gretchen Baker Changing Faces: A Recent History of Snow Surveys in GRBABy Gretchen Baker, Ecologist and Meg Horner, BiologistOne of the oldest datasets in the Park is the Baker Creek Snow Survey, with three snow courses located in the Baker Creek watershed. Since 1941, the snow has been measured in late February and late March every year (and in some years also late January and late April).Snow survey data is managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). When I (Gretchen) started at GRBA in 2001, the surveys were run by two NRCS employees, including Curt Leet, with help from Rob Ewing (GRBA LE) and volunteers Jeff Woodruff and John Woodyard. I heard stories of how hard it was and was a bit intimidated. The 300% snowpack in 2005 resulted in them being dropped off by helicopter high up in the Baker watershed and skiing downhill so they wouldn’t have to break trail uphill through such deep snow. That sounded super cool, but also beyond my rudimentary cross-country ski level. Around 2010, Law Enforcement staff changed, and Jacob Wahler was sent out to assist. He had never even been cross-country skiing. He survived, so I decided I would give it a try in 2011. It wasn’t easy, but with skins to help me get extra traction on the snow, I had enough control to make it doable and fun. Jacob left the park, and no other law enforcement staff wanted to continue, so park resource management stepped in to assist , particularly Meg Horner and Ben Roberts. NRCS staff retired and moved, and a few years later Nicole Bolton started working for the NRCS in Ely. She quickly learned to cross-country ski and started helping with surveys. The Baker Creek snow course has three sites: one just above the trailhead at about 8,200 feet elevation, another about 2 miles up the trail, and a third about 3 miles up the trail at 9,500 feet elevation. If we can get to the trailhead by driving or UTV, that means we can do the snow survey in about 8 hours. Otherwise, it is a long day lasting 10 or more hours. The best conditions are when we have good snowpack and recent snowfall. In years with minimal snowpack, we must take off our skis multiple times to avoid lots of obstacles. When we get to each of the three snow courses, we assemble the three snow tubes, measure the distance to each of the five sites where we sample the snow, and drive the tube into the snow. We read snow depth, the length of the snow core in the tube, and then weigh the tube and snow in the tube to get the Snow Water Equivalent, or SWE. The SWE basically represents how much water would be covering the area if all the snow melted. Thanks to all who have helped with snow surveys. Over the past 15 years that includes (in alphabetical order): Gretchen Baker, Joanie Bernardi, Nicole Bolton, Chandra Conrad, Joey Danielson, Meg Horner, Nancy Herms, Bryan Hamilton, Jenny Johnson, Curt Leet, Julie Long, Greg Moore, Mark Pepper, Ben Roberts, Brooke Safford, Peter Super, Andrea Wagner, Jacob Wahler, Jeff Woodruff, Liz Woolsey, and John Woodyard. If you’d like to learn more about the science behind snow surveys, plus great tips for staying safe in the backcountry in the winter, you can check out the online snow survey training: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLWioilqNQcrHpmDl8kFZpchn5QlDVU-ze Selected Publications about the Park

Upcoming Events

Illustration by Emily Hale More informationThe Midden is the Resource Management newsletter for Great Basin National Park. A spring/summer and fall/winter issue are posted each year. We welcome submissions of articles or drawings relating to natural and cultural resource management and research in the park. They can be sent to: Resource Management, Great Basin National Park, Baker, NV 89311 Or call us at: (775) 234-7331Superintendent: James Woolsey Acting Integrated Resource Management Program Manager: Bryan Hamilton Editor & Layout: Gretchen Baker What’s a midden?A midden is a fancy name for a pile of trash, often left by pack rats. Pack rats leave middens near their nests, which may be continuously occupied for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. Each layer of trash contains twigs, seeds, animal bones and other material, which is cemented together by urine. Over time, the midden becomes a treasure trove of information for plant ecologists, climate change scientists, and others who want to learn about past climatic conditions and vegetation patterns dating back as far as 25,000 years. Great Basin National Park contains many middens. |

Last updated: November 2, 2022