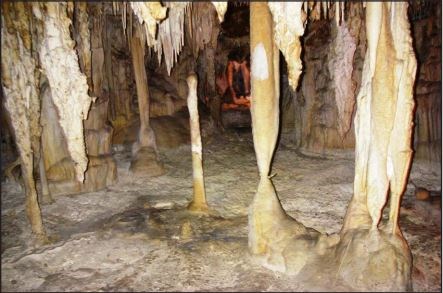

NPS Photo Gretchen Baker International Year of Caves and Karst 2021By Gretchen Baker, EcologistGreat Basin National Park is participating in the International Year of Caves and Karst 2021, a celebration of our natural underground spaces. This year we also prepare to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the designation of Lehman Caves National Monument on January 24, 2022. A public ceremony will be held at the Park on August 6, 2022. Some fun stats about caves and karst at Great Basin National Park: -Lehman Caves was rediscovered in 1885 by Absalom Lehman and opened as Nevada’s first show cave -Thirty-nine other caves in the Park have since been explored -The Park is home to the longest cave in Nevada: Lehman Caves, at slightly over 2 miles long -The Park is home to the deepest cave in Nevada: Long Cold Cave, at over 400 feet deep -The Park is home to the highest elevation cave in Nevada: High Pit, at over 11,000 feet elevation -The Park has annual cave rescue practices to ensure visitor and staff safety. -Numerous measures in Lehman Caves have been enacted to make the cave safer, such as an electrical lighting system, non-slip surfaces on the pathways, handrails, and more headspace in passages that were previously crawlways. -Annual lint and restoration camps (Covid permitting) help reduce human impacts to Lehman Caves -Bat gates on several caves help protect the bat populations within them -Cave management plans outline several other conservation measures, such as fire retardant drops near caves and a wild cave permit system. -Lehman Caves has 504 cave shields, perhaps the most of any cave in the world -The condensation corrosion in Lehman Caves (where carbon dioxide has dissolved away rock and speleothems) has recently been recognized as one of the best examples in the world. The NPS has monthly themes and highlights. The next page shows an image for each of the monthly themes.

NPS photo Bryan Hamilton 2021 Reptile BioBlitzBy Bryan Hamilton, Wildlife BiologistReptiles are a diverse group that includes nearly 10,000 species. The vast majority of reptiles (~95%) are snakes and lizards. Nevada supports over 50 species of snakes and lizards, where the desert climate and large, undeveloped, open spaces are ideal habitat. However, reptiles are declining worldwide. Reptiles are ectothermic or cold blooded. Some species lay eggs and other species have live birth. Most reptiles are both predators and prey. Climate change is interacting with these life history traits and affecting the distribution of reptiles across the globe. Invasive plants like cheatgrass are also impacting species such as horned lizards which depend on open habitat to avoid predators. Other reptiles such as Burmese pythons have been introduced outside their native range, causing dramatic changes to ecosystems.Surveys are important to understand the role of reptiles in ecosystems. However, reptiles can be difficult to find. Many species are rare, well camouflaged, or live underground. This makes it challenging to quantify distribution, population trends, and habitat associations. A BioBlitz is a short-term event to learn about the biodiversity of an area. In Great Basin National Park, we focus on one specific taxa, either plant or animal, each year over 48 hours. This snapshot view helps us look at a variety of habitats over the same time period and helps us better understand what lives in the park. This year the BioBlitz will focus on reptiles. Join Dr. Bryan Hamilton, Dr. Chuck Peterson, Jason Jones, Meg Horner, Jeremy Westerman, other herpetologists, and Park staff to learn more about snakes and lizards June 11-13, 2021. We will use iNaturalist to document our sightings, which can be in the Park or where you live. One of our main goals is to encourage an appreciation of reptiles all over. Data collected from this year’s BioBlitz will be compared to survey data over the last 20 years. These data will be compared with survey data over the last 20 years. This comparison can help us see if reptiles are changing in response to climate or habitat conditions. Check the Park website for more information. If you would like to be added to the BioBlitz email list e-mail us.

application. NPS photo Julie Long Short Recap on Strawberry Creek CanyonBy Julie Long, Biological Science TechnicianIn 2016, a lightning-ignited fire burned over 2,700 acres of the Strawberry Creek watershed in Great Basin National Park. Park biologists have partnered with the Nevada Department of Wildlife, the Bureau of Land Management, and other agencies to treat, restore, and monitor the area post-fire.Over the past four years, park staff have performed vegetation surveys along with fish population and habitat surveys, completed aerial and hand seeding using a native seed mix, and monitored and treated invasive plant species. Implementing restoration strategies not only prevents the establishment of invasive plant species and limits soil erosion, but it also supports the establishment and persistence of native vegetation, wildlife, and fish populations. Strawberry Creek Restoration

Left image

Right image

NPS photo Julie Long Learning More about WeedsPre-fire there was: musk thistle, bull thistle, Canada thistle, whitetop, spotted knapweed, horehound, and cheatgrass. After the fire we found new invasive plant infestations that were not recorded before the fire. Those species are sow thistle and houndstongue (AKA gypsy flower). What is the most common weed in the rest of the Park? Bull thistle What is the first line of defense against weeds? Early detection and rapid response are essential when preventing the establishment of nonnative populations.

NPS photo Bryan Hamilton Nevada Bat PlanBy Bryan Hamilton, Wildlife BiologistOn warm summer nights, vast numbers of bats fly above our heads. Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight and use high frequency echolocation calls to detect and capture insect prey. Because we can’t see or hear them, we are largely unaware of the incredible abundance of bats.All of the 23 species of bats found in Nevada feed on insects. Bat predation on insects in the United States is valued at $53 billion each year through reduced food costs, need for harmful pesticides, and disease risk from insect vectors such as mosquitoes! Therefore, protecting and conserving bats is extremely important for human health and the economy. The Nevada Bat Conservation Plan was published in 2006 to guide bat conservation in Nevada. Since then we’ve gained new knowledge about bats and new threats to bat populations have emerged. White-nose syndrome (WNS), a fungal disease, has spread across North America in the last decade, killing millions of bats in its wake. Wind energy development has proved deadly to bats, threatening the population viability of migratory species such as hoary bats. It is time for a new Nevada Bat Conservation Plan. An interagency group representing the Nevada Department of Wildlife, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and Nevada Division of Natural Heritage are currently revising and rewriting the Nevada Bat Conservation Plan. A newly revised Nevada Bat Conservation Plan will include information on habitat, public health, species accounts, threats, and survey methods. This document will help protect bats in Nevada for the next decade.

Glacier. NPS photo Gretchen Baker A Peek Inside the Wheeler Cirque GlacierBy Gretchen Baker, EcologistI’ve trekked on glaciers in Alaska, Mt. Rainier, New Zealand, and Argentina, but had never gotten a really good look at Great Basin’s Wheeler Cirque Glacier. I was able to remedy that in September 2020. I received an email in the spring of 2020 from some glacier enthusiasts who are trying to bring more awareness of glaciers retreating. They came to the Park in September. That happens to be a good time to get a look at the glacier, so I invited them along as I re-photographed the ice glacier from about the same vantage point it was photographed in 1958.As we looked at the old photo and tried to find the same place, we realized just how much the glacier had shrunk. The dark line on the rock was much higher, and more rock was visible. Even more telling was that the people who were walking on some rocks on the glacier in 1958 were walking on a gentle slope, while in 2020 the slope is quite steep. We estimated that the ice level was about 40-60 feet lower in 2020 than in 1958. After getting the photo, I wanted to take a look inside the crevasse. I secured my crampons, grabbed my ice axe, and climbed up to the crevasse. Upon arriving, I took out the DistoX, a laser we use for cave surveying, and measured the deepest spot in the crevasse, which was about 20 feet deep. The back side of the crevasse consisted of rock, and the front side was all ice, some of which was melting. It was strange reflecting on how much of the cirque the glacier used to cover. During the last Ice Age, it flowed down the Lehman Creek drainage to about the distance of Mather Overlook. During a previous Ice Age, it flowed even farther, stopping just short of Upper Lehman Campground. Today we have lots of evidence of these past glaciers, with moraines, cirques, and more. The glacial ice, both exposed and in the rock glacier, helps provide a water source in late summer, when many other water sources have dried up. The cool ice supports a flock of gray-crowned and black rosy finches, who fly from one spot to another to eat insects that have fallen into the snow and ice. For the moment, we still have a tiny alpine glacier above the rock glacier, but based on the rapid warming the Park is experiencing, it is likely to disappear in the near future.

with night sky viewing. Gretchen Baker Changes in the Park-New Astronomy Amphitheater opens in 2021, with programs on Thursday and Saturday nights throughout the summer. -A Bronze sculpture of Wheeler cirque and rock glacier was installed in August 2020 and provides a new way to view the high elevations. A video of the artist, Bridget Keimel, explaining her creative process is also available to watch. -Lehman Caves Visitor Center exhibits are open. These fantastic exhibits focus on Discover the Dark, with cave and night sky sections. -Wheeler Peak Campground is closed for renovations this summer. Grey Cliffs, Upper Lehman, and Lower Lehman Campgrounds are open by reservation only. Much of June and July are already full, so plan ahead! First-come first-served camping at Baker Creek Campground and along Snake Creek. -Lehman Cave tours resume in 2021! Tours are limited and it’s highly recommended to book ahead on recreation. gov. Tours enter and exit through the Exit Tunnel. If you can’t visit in person (or want to get a different perspective), the Virtual Cave Tour is available for free. Selected Publications about the Park

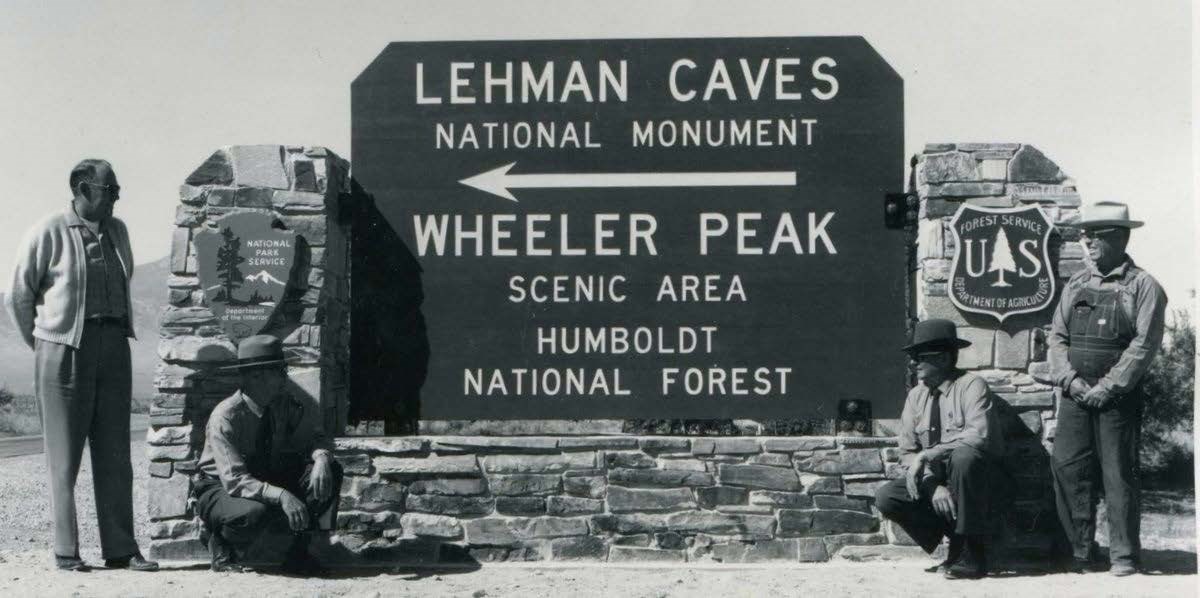

National Forest until its inclusion in Great Basin National Park in 1986. NPS photo Can You Match the Important Dates in Great Basin National Park History?(Answers below in upcoming events)

Upcoming Events

More informationThe Midden is the Resource Management newsletter for Great Basin National Park. A spring/summer and fall/winter issue are printed each year. The Midden is also available on the Park’s website at www.nps.gov/grba. We welcome submissions of articles or drawings relating to natural and cultural resource management and research in the park. They can be sent to: Resource Management, Great Basin National Park, Baker, NV 89311 Or call us at: (775) 234-7331Superintendent James Woolsey Natural Resource Program Manager Ben Roberts Cultural Resource Program Manager Eva Jensen Editor & Layout Gretchen Baker The Midden National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior What’s a midden?A midden is a fancy name for a pile of trash, often left by pack rats. Pack rats leave middens near their nests, which may be continuously occupied for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. Each layer of trash contains twigs, seeds, animal bones and other material, which is cemented together by urine. Over time, the midden becomes a treasure trove of information for plant ecologists, climate change scientists, and others who want to learn about past climatic conditions and vegetation patterns dating back as far as 25,000 years. Great Basin National Park contains many middens. |

Last updated: November 20, 2021