Denver Public Library

Denver Public Library The Old Army was the army that existed before the Second World War. Women and children were an important part of its story. They shared many of the experiences of garrison life. The tribute to the “Ladies of the Army” in the popular ballad of the day Benny Havens O!! was often heard among West Point cadets and young officers of the army. Along with the lilting tune of The Girl I Left behind Me these were musical salutes that women were in the thoughts of soldiers and that they went with the men no matter how far or dangerous the journey was. As one of the young brides put it, “I had gone for a soldier and a soldier I determined to be.” What kind of woman was an army wife? She has been described “as a kind of tough, weather proof, India rubber woman, serene and unruffled in all situations.” What attracted them to the military life? Daughters of officers had the advantages of proximity and an ample choice of husbands among young officers. For others who knew nothing of the army the appearance of an officer was a glamorous event. Military glory charmed and dazzled many young women who soon learned the difference of real life from fancy. Once married soldiers and wives had few romantic sentiments. The hard realities of army life eradicated such nicetie. There were the upheavals of the frequent changes of station. It was a fact of army life that as soon as one was comfortable, orders for another station were received. The army provided transportation for officer’s families. An alternative to these frequent upheavals was for an officer to go alone to his next posting while his family stayed in more pleasant circumstances and a baggage allowance dependent on rank. An alternative to these frequent upheavals was for an officer to go alone to his next posting while his family stayed in more pleasant circumstances. His wife avoided the discomfort and danger of a hard journey and the difficulties of making a home on a frontier post. The children had the benefits of a school and a more civilized environment. After a year he usually obtained leave to spend time with his family and there was always hope that his next assignment would allow his family to join him For most army wives marriage meant a long journey that could prove arduous. One such trip was described by Alice Dryer. It consisted of a three week sea voyage to California marked by storms and sea sickness. This was followed by three more weeks of travel in mule drawn wagons across the desert to Fort Yuma Arizona. Even trips east of the Mississippi were rigorous. It took two months via stage coach, Lake Schooner, and canoe from Hartford Connecticut to Fort Crawford on the Mississippi River. These trips were often fraught with danger. The most tragic was the voyage of the Third Artillery Regiment on the steamer San Francisco. In 1853, 520 men, women, and children sailed from Governors Island in New York City bound for California. The ship was caught in a storm off Cape Hatteras North Carolina with over 250 lost in its sinking. The eight week journey of the 700 strong Fourth Infantry and their dependents from New York City to California via Panama was recorded by Captain U.S. Grant in his memoirs. In Panama over 100 soldiers and seventeen out of twenty children died of a cholera outbreak. These journeys were tinctured with both fear and curiosity. Travelling to and living in strange places, army wives absorbed the sights and sensations of new country and different people. The beauty of the forests, the grandeur of the mountains and the sea, the beautiful flowered prairies in the spring evoked comments as did the harshness of the deserts.

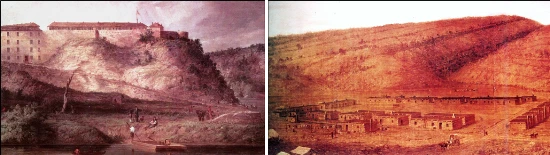

Architect of the US Capitol

American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming When the journey was over, army wives often faced bleak prospects of life at a crudely thrown-together post. Fifth Infantry wives lived in shelters created out the boats that transported them to Fort Snelling for five weeks. Tumble down log cabins were common. In Texas and Arizona, backyards often contained tarantulas, scorpions, centipedes and an occasional rattlesnake. Desert posts were harsh environments with summer temperatures often reaching 110-120 degrees inside the adobe quarters that were common at posts like Fort Defiance New Mexico. At army posts there were usually children and their presence was a comfort but also a worry. Death was a frequent worry in the primitive environment of frontier posts and the many small graves in post cemeteries were a doleful reminder of their fate. If their children survived infancy the parents had to face the anxieties of frontier life and the problem of education. Most parents wanted their children to learn the fundamentals of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Some solved the problem by children with family or friends in more civilized locations when they were of school age. Some posts established schools and others taught their children themselves. The Army, however, eventually accepted some responsibility for education. Post councils of administration provided funds for hiring teachers to provide instruction. In 1838, Congress authorized Chaplains. One of the reasons for this step was to furnish teachers to frontier posts. These post schools seemed to provide a solid dose of educational fundamentals. As army wives looked back on this time before the Civil War, they described army life as “days of small things”. The Army was small and the posts tiny. The combination of small size and isolation could mean a pleasant intimacy. Many army wives characterized the relationship between officer’s families as family. Their experiences bound them together. The Army was their home and women and children became part of the Army and the Army part of them. After the Civil War, army life returned to its peacetime ways. One of the changes in army life was new larger posts within easy reach of railroads. This helped eliminate many of the hardships of travel and frontier life. However army officer’s wives and families still led a nomadic existence on the frontier that was both bleak and dangerous. After the infrequent interlude of duty on quiet Eastern posts, they faced flash floods, scorpions, wild animals and Native Americans of uncertain disposition.

NPS/Fort Davis National Historic Site Women who followed the army endured both boredom and danger. They had no particular duties because soldiers and servants cared for the household needs including childcare. Also absent was a social life outside the post, and an economic role in the community. They had to be ready to move to a new post or give up their home to a newly arrived senior officer’s family at very short notice. Boredom was broken by intense periods of worry when the regiment was on campaign and danger when hostile Native Americans attacked the post. On those occasions, women and children were ordered to their homes, and one officer was given the difficult duty of shooting them if the post was overrun and in danger of being taken captive. This extreme measure was never necessary. Officer’s wives had no official position according to Army regulations. Women created their own closed society on Army posts, bonding across rank and class to aid a woman in childbirth, or to organize some brief and irregular schooling for the post’s children. Otherwise, society and official duties overlapped and rank prevailed among wives as among officers and enlisted men. Each woman had to make her own decisions about whether or not to live at the post, travel with her husband, or return to her parents house to see to her children’s education. If a wife stayed, her husband’s career became her own. This choice was easily justified in light of the nineteenth century concept of True Womanhood, which applauded subordinate and pious women. They supported their husband’s careers through social networks and attending to his personal and social needs. She had a vital public role that was often mutually beneficial and many wives wrote of “our promotion.” Army life wasn’t all duty and hardship however. Officer’s wives had servants (often enlisted men called “strikers”), fine horses, and military escorts when rode or walked off post. When not engaged in military affairs, couples and single officers attended “hops” and balls, hunts, picnics, card parties or masquerades several times a week. During the last three decades of the nineteenth century on the frontier, army women and children continued to share the isolation, hardship and fears of army life. The women brought amenities to an otherwise unbearably bleak barren life, while children provided a poignant mix of pleasure and worry. These army wives were very much part of frontier army life that disappeared so rapidly hat it made many conscious that they played a role in army history. |

Last updated: February 26, 2015