|

During summer 2018 the National Park Service began a project with the objectives of using repeat photography techniques to document changes in the physical, biological, and cultural landscape of Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve (GAAR), Alaska and to better understand the history of geologic exploration of the park and surrounding area. It is critical for effective park management to understand how the natural resources of GAAR have changed during the past century and how the ecosystems and landscape of the park are responding to stressors such as climate change and human visitation and development. Repeat photography was selected as the investigation method for this project because it is an efficient tool for documenting landscape changes and communicating the complex effects of climate change to diverse audiences including park visitors, resource managers, and scientists.

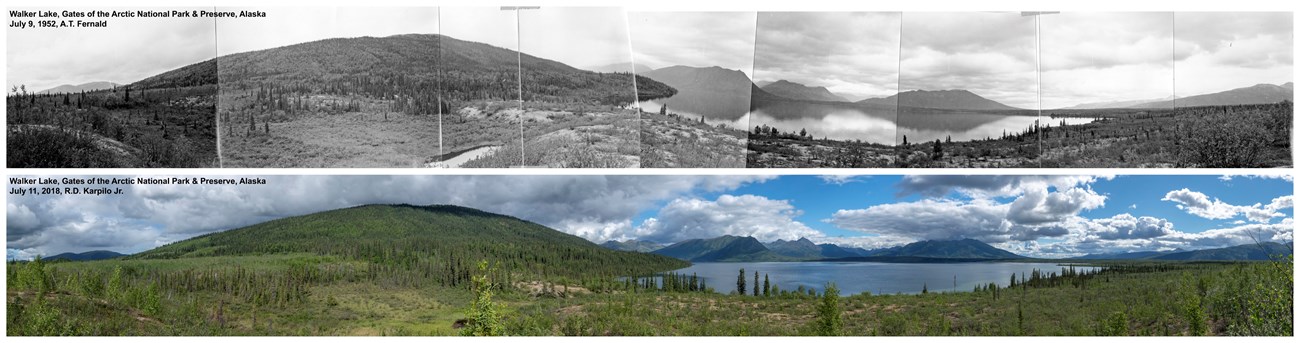

What is Repeat Photography?Repeat photography is a cost-effective tool used by scientists and researchers monitoring landscape changes. It has also become a valuable tool in communicating the effects of climate change such as glacial recession. The concept of repeat photography is similar to that of marking a child's growth on a door frame. One returns to the same location at a later date to record the change that has occurred during the intervening period of time. Modern photos of a subject are taken from the same vantage point at different points in time.On the following images, move the center slider to compare the changesView north from Swan Island, Walker Lake

Left image

Right image

Study AreaGAAR, the second largest and least visited National Park in the U.S., is a remote, roadless wilderness park located above the Arctic Circle in the Brooks Range in Alaska. The isolated nature and lack of infrastructure present significant challenges for studying and managing park resources. Walker Lake was selected as the focus for the 2018 field season because of the concentration of high quality historical photos, access to the area by float plane from Bettles, AK, and the fact that Walker Lake serves as a starting point for many Kobuk River float trips and accordingly is one of the most visited locations in the park. Walker Lake is almost 14 miles long and averages more than 1 mile wide, with elevations ranging from 600 feet at the lake to over 4,000 feet on many of the surrounding peaks. The lake was designated a National Natural Landmark in April 1968. The Walker Lake Natural Landmark Brief describes the significance of the area as:This lake provides a striking example of the geological and biological relationships of a mountain lake at the northern limit of forest growth on the south slope of the Brooks Range. A full range of ecological communities from the dense white spruce forest of its shores to the barren talus slopes 2,000 feet above the lake document the rapid biological change in a markedly compressed linear distance. Some of the dominant habitat forms are open spruce forest, tall shrub, dry tundra, bluffs-slides outcrops, and standing waters. Other types presented in small amounts include low shrub, tussock-heath tundra, sedge-grass marsh, and flowing waters. Animal life here is well representative of that of northern Alaska (National Park Service, 2010).

View northeast from the terminal moraine on the southern shore of Walker Lake

Left image

Right image

USGS ExpeditionsThe U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) conducted numerous expeditions and surveys in Alaska during the past 125 years. The authors evaluated several USGS expeditions in the GAAR area and decided to focus on the trips by USGS geologists Walter C. Mendenhall in 1901 and Arthur T. Fernald in 1952 because they both made high-quality photographs during their fieldwork and the dates of the expeditions provide nicely spaced snapshots of GAAR resources 117 and 66 years ago respectively. Mendenhall’s 1901 reconnaissance expedition “was carried out in pursuance of a plan which has been followed for some years by the United States Geological Survey in the topographic and geologic exploration of the little-known parts of Alaska and in the collection of such information as will be of value not only to the scientific world, but to the prospector, the miner, and the trader (Mendenhall, 1902).”The expedition also investigated the known and probable locations of gold and other economically desirable minerals, made observations about the distribution of fish, game, and plants (including the collection of numerous botanical specimens), collected meteorological data, and provided notes about the local native populations they encountered. The field party was led by Mendenhall (geologist) and the topographic work was conducted by Dewitt L. Reaburn (topographer), camp hands and assistants included: R.C. Applegate, W.B. Reaburn, W.W. Von Canon, George Revine, and W.L. Poto. The expedition left Fort Yukon on the Yukon River on June 8th and arrived at the newly formed mining town of Deering on the south shore of Kotzebue Sound on September 15th. The party covered a total of 1,169 miles traveling in lightweight Peterboro canoes, which they rowed, paddled, poled, sailed, tracked, or carried up and downstream several rivers and over two portages (totaling 23.5 miles and 2,800 feet of vertical elevation gain). Fernald’s 1952 fieldwork was conducted in connection with the study of Alaskan terrain and permafrost and was financed in part by the Engineer Intelligence Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army. The field party included: R.S. Sigafoos (botanist), M.D. Sigafoos (botanist), D.R. Nichols (geologist), and Sam White (bush pilot). The expedition was based near the village of Shungnak and used a float plane to visit several lakes near the Kobuk River and made canoe traverses down the Ambler, Mauneluk, and Kobuk Rivers. View east from the terminal moraine on the southern shore of Walker Lake

Left image

Right image

MethodsThe authors conducted literature searches and visited the USGS Denver Library Photographic Collection in Denver, Colorado to identify and scan historical images taken in the GAAR area. The photographs, publications, and maps from the Mendenhall and Fernald expeditions were used along with consultation with GAAR staff familiar with the area to map the photographers’ probable locations. Twelve sites were identified near Walker Lake. During July 2018, a three-person NPS team flew from Bettles, AK via float plane and spent a week at Walker Lake locating and repeating images at six of the twelve sites. The photographs were repeated using a Nikon D850 45.7 megapixel DSLR camera with Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 or 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom lenses. For panoramic images, a specialized panning clamp and nodal slide were mounted on the tripod to create a series of individual images without parallax that could be digitally stitched together into a high-resolution seamless single-row panoramic image. In addition to repeating the historical photo, a 360º panorama was made at each site. Reference shots of each photo point were taken to aid in precisely relocating the sites in the future. The coordinates, elevation, camera direction, location description, camera setting, and all other relevant metadata were recorded for each site.GAAR, the second largest and least visited National Park in the U.S., is a remote, roadless wilderness park located above the Arctic Circle in the Brooks Range in Alaska. The isolated nature and lack of infrastructure present significant challenges for studying and managing park resources. Walker Lake was selected as the focus for the 2018 field season because of the concentration of high quality historical photos, access to the area by float plane from Bettles, AK, and the fact that Walker Lake serves as a starting point for many Kobuk River float trips and accordingly is one of the most visited locations in the park. Walker Lake is almost 14 miles long and averages more than 1 mile wide, with elevations ranging from 600 feet at the lake to over 4,000 feet on many of the surrounding peaks. The lake was designated a National Natural Landmark in April 1968. The Walker Lake Natural Landmark Brief describes the significance of the area as: This lake provides a striking example of the geological and biological relationships of a mountain lake at the northern limit of forest growth on the south slope of the Brooks Range. A full range of ecological communities from the dense white spruce forest of its shores to the barren talus slopes 2,000 feet above the lake document the rapid biological change in a markedly compressed linear distance. Some of the dominant habitat forms are open spruce forest, tall shrub, dry tundra, bluffs-slides outcrops, and standing waters. Other types presented in small amounts include low shrub, tussock-heath tundra, sedge-grass marsh, and flowing waters. Animal life here is well representative of that of northern Alaska (National Park Service, 2010). View south from the southeast shore of Walker Lake

Left image

Right image

View south from the southeast shore of Walker Lake

Left image

Right image

Study Area ResultsPreliminary analysis of the photo pairs show that overall there has been relatively little change in the Walker Lake area over the past century. The primary discernable changes in all the pairs are variations in density, distribution, and size of vegetation such as white spruce (Picea glauca), black spruce (Picea mariana), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), and willows (Salix spp.). Specifically, the trees have increased in size and number and there is a general increase in shrub density (visible in all photo pairs). Shrubs have filled many of the previously open areas and thickened along the lakeshore and in stream channels. Additionally there is a slight upslope advance of tree line. These findings are likely a result of warming climate and are consistent with the results of other arctic studies (Myers-Smith et al. 2011; Swanson, 2013; and Tape et al. 2006). The increase in shrubs may have altered local hydrologic regimes by changing stream morphology, increasing summer transpiration, and collecting and stabilizing winter snow (Sturm et al. 2001). A better understanding of the wildfire history of the area is necessary to determine if any of the observed vegetation changes can be attributed to fire-related recovery.Also notable is the almost complete absence of visible anthropogenic disturbance or development. The only exception is a small cabin on the east shore of the lake that is noticeable under extreme magnification in the 2018 image. The overall intact ecosystem and pristine and untrammeled character of the study area is likely a result of the combination of the remote nature of the park and successful NPS management policy and practices that support the founding purpose of GAAR; which is “to preserve the vast, wild, undeveloped character and environmental integrity of Alaska’s central Brooks Range and to provide opportunities for wilderness recreation and traditional subsistence uses (National Park Service, 2009).” This project contributes to the understanding of the history of scientific exploration in GAAR and provides information about how park resources in the study area have changed or remained stable over the past century. The photo pairs produced by this project will aid in identifying specific features or processes that may require more intensive monitoring and research and will be a useful tool for education, outreach, and resource management. At this point, only a cursory examination of the pairs has been completed. At a later date, a more comprehensive analysis of the photo pairs should be conducted; including: identification of individual species present, delineation of vegetative communities, study of the wildland fire history of the area, and further analysis of the changes observed. There were several additional photo sites in the upper portion of Walker Lake and along the Kobuk River that the authors were not able to visit due to limited field time. These sites could be completed on a future trip. The authors focused on only a very small subset of Mendenhall and Fernald’s images. There are many additional historical photos from these expeditions and others that should be evaluated for their potential repeat value. Future repeat photography work could expand to additional portions of GAAR and other parks. This webpage content was adapted from: Karpilo Jr., Ronald D., Allan, Chris, Rasic, Jeffrey T. and Heise, Bruce A. (2018) Repeat Photography of Historical U.S. Geological Survey Expedition Photographs in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, Alaska. Poster presented at the 2018 GSA Annual Meeting, Indianapolis, Indiana. Download the poster Special thanks to the USGS Denver Library Photographic Collection staff for providing research assistance for this project. ReferencesFernald, A.T., 1964, Surficial geology of the central Kobuk River valley, northwestern Alaska: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1181-K, p. K1-K31, 1 sheet, scale 1:250,000.Mendenhall, W.C., 1902, Reconnaissance from Fort Hamlin to Kotzebue Sound, Alaska, by way of Dall, Kanuti, Allen, and Kowak rivers: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 10, 68 p., 2 sheets. Myers-Smith, I.H., B.C. Forbes, M. Wilmking, M. Hallinger, T. Lantz, D. Blok, K.D. Tape, M. Macias-Fauria, U. Sass-Klaassen, E. Lévesque, S. Boudreau, P. Ropars, L. Hermanutz, A. Trant, L. Siegwart Collier, S. Weijers, J. Rozema, S. A. Rayback, N.M. Schmidt, G. Schaepman-Strub, S. Wipf, C. Rixen, C.B. Ménard, S. Venn, S. Goetz, L. Andreu-Hayles, S. Elmendorf, V. Ravolainen, J. Welker, P. Grogan, H.E. Epstein and D.S. Hik, 2011, Shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems: dynamics, impacts and research priorities. Environmental Research Letters 6: 045509 doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/045509. National Park Service, 2009, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve Foundation Statement. Retrieved October 28, 2018: https://www.nps.gov/gaar/learn/management/upload/a-GAAR-Foundation-Statement.pdf. National Park Service, 2010, Walker Lake Natural Landmark Brief, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Natural Landmarks Program. Sturm M., C. Racine, and K. Tape, 2001, Increasing shrub abundance in the Arctic. Nature, 411, 546–547. Swanson, D.K., 2013, Three decades of landscape change in Alaska’s Arctic National Parks: Analysis of aerial photographs, c. 1980-2010. Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/ARCN/NRT—2013/668. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Tape, K., M. Sturm, and C. Racine, 2006. The evidence for shrub expansion in northern Alaska and the pan-arctic. Global Change Biology 12:686–702. |

Last updated: August 23, 2019