In 1772, Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the British Government, and the wealthiest man in the Mohawk Valley, was looking to consolidate and strengthen his power. He convinced Governor William Tryon to turn the Mohawk Valley into a separate county. He also pushed to have the county seat located in his growing settlement of Johnstown by offering to pay for the construction of the courthouse and jail. Johnson learned in March that the new county was to be created, and later that spring, that Johnstown would become the county seat. As the county officials would be appointed by the governor, Johnson had a list of names ready to send to the governor to ensure men loyal to him would oversee the county government. It probably came as quite a shock to him then when he received a letter on March 20, from an Alexander White. In the letter, White informed Johnson that that Governor Tryon had appointed him to be the Sheriff of Tryon County.

Whatever qualifications White may or may not have had, one thing he was not lacking in was confidence. Confidence with a healthy dose of ego mixed in. In his letter to Johnson, White stated that he was “not doubting his…Appointment will meet with your Approbation; especially as I am well acquainted with a great Number of the Inhabitants of the said county, having commanded at Fort Harkaman (Herkimer) in the Year 1764.”

If Sir William had any initial misgivings about White, they were apparently put to rest as White was still serving as sheriff when Johnson died in July of 1774. White proved himself to be a staunch supporter of royal authority. That may have strongly influenced Johnson’s continued backing of the sheriff as strife between Great Britian and her colonies mounted in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War. Unfortunately for Sheriff White, Johnson’s death loosened the total control over Tryon County that he and his extended family had enjoyed for so long.

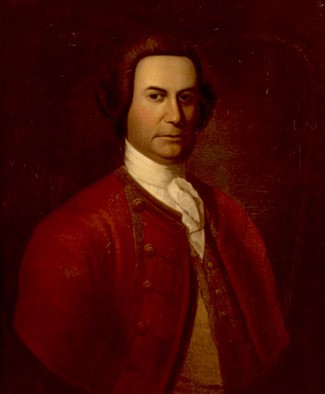

BELOW: Portrait of Sir William Johnson.

This, coupled with White’s overconfidence and rather conceited and antagonistic manner, would prove to be his undoing. As rebel activity in the Mohawk Valley intensified, White became very outspoken concerning his feelings for his rebel neighbors. County Committee of Safety members would later testify to White’s haughty manner:

Major Jelles Fonda: “…he heard the Sheriff say oftentimes, that he would fight for his King and Country with his association and the party on the King’s Side like a brave Man, and swore to be Sure, that they would conquer, but the party on the Country’s side do fight with halters on their Necks-He also heard him many times declare, that he hopes to have the pleasure of hanging a good Many yet for their Resistance against the Acts of Parliament…”

William Seeber: White had come to Seeber’s house on business on a day that men had been signing an “association” pledging to support the resolves of the First Continental Congress. In the course of conversation the sheriff said “…with many Curses, that if he had been this day by signing the Association he would have shot some of ’em through their hearts and the Rest he would have carried away to the Westward, to be hanged there…” Seeber’s son remonstrated against the sheriff: “Whereupon the Sheriff got his pistol, cocked it and presented it to the Breast of said Jacob, saying: You d…d Rebell, if you say one Word more, I’ll blow your Brains out…”

There is no know description or portrait of Sheriff White. Below is modern depiction of a New York Sheriff comes from the description of aFrench prisoner in 1760. According to theprisoner, a white staff or rod was the only “badge” carried by an English sheriff.

Sheriff White also seemed to have a flair for theatrics as well. In a later report to the Albany County Committee of Safety, the Tryon Committee reported that “on a Sunday, he spread a long Rope across the Road leading to Church and hung Sticks to it, told People as they came to Church that the Sticks represented Committee People and named some,” inferring he’d soon hang them.

It appears that Sheriff White also saw no issue with attempted extortion against those of a rebel leaning. Dr. William Petry testified that he was in Johnstown searching for a runaway servant and:

“…the Sheriff White stopped the Deponent in the Street, and told him, that he must go to goal (jail). Whereupon the Deponent enquired for the Writ against him, or any other Reason, Why he should go to Goal, but the said Sheriff replied shortly to him that it is to late to give this prisoner close…” The next day White wrote a bail notice for 60 pounds, ($81 per the modern exchange rate) promising Petry he would be immediately released once he signed it. Petry refused to sign, and ended his testimony thus: “…after some hours past, the Jailkeeper ordered the Deponent out of the Goal again, without any Bail or Recognizance…”

It was William Wallace’s testimony, however, that would point to the two families that became Sheriff White’s particular nemeses: “that Sheriff White did one day…publickly say-The Estates of the Country here are all forfeited. Especially pointing upon Adam Fonda and Sampson Simons (Sammons), and the people will be hanged…”

The Fondas and the Sammons had come to the forefront in leading open radical activity against royal authority in the Mohawk Valley so it is no surprise that Sheriff White would single them out for particular abuse. It was, in fact, an altercation with another Fonda that brought about the above quoted testimonies as well as the sheriff’s fall from power. Perhaps it was the fact that both White and the Fonda’s lived in the Caugnawaga (modern Fonda, NY) area that made the Fondas a convenient target for White’s ire. If one had no knowledge of the underlying reasons for their mutual dislike however, the incident started out looking more like a neighborhood feud than anything to do with politics.

On June 25th of 1775, a servant of Sheriff White, Thomas Hunt, crossed over one of John Fonda’s fields newly sown with meadow grass and peas. It appears that Hunt did it intentionally as there was a path around the field which he ignored and directed abusive language at Fonda when told to use the path. Hunt was carrying a brush hook and threatened to strike Fonda with it, upon which Fonda knocked him down with the hoe he was using. What was no doubt an underlying cause for Hunts actions, however, was the Fonda family’s standing as ardent rebels.

Sheriff White eventually arrested Fonda and put him in the county jail in Johnstown. It appears that by this point the rebels had finally had enough of White’s obnoxious and antagonistic ways. On July 20, a group of around 50 valley residents under Sampson Sammons marched to the jail and released Fonda. White was in Johnstown at the time, and the mob then went to the tavern of Gilbert Tice (later accounts turn the name into Mattice), where White was staying, intent on capturing the sheriff. According to valley history, White, looking out a second-floor window, spotted Sammons at the front of the mob and fired a pistol at him. The ball whizzed past Sammons’s head, and the mob returned fire, slightly wounding White. Valley historians consider this the “first shots of the revolution” fired in Tryon County. The mob then broke in the tavern door and began searching for White, who it’s said, was attempting to delay his capture by hiding in a chimney. At this point, however, the mob heard the alarm guns sounding at Johnson Hall and knowing that Sir John Johnson could soon be there with a large number of men, the mob scattered. Sheriff White then took shelter at Johnson Hall.

We shall for now leave Sheriff White in safety at Johnson Hall and finish his story in the next installment.

BELOW:

The original Tryon County jail built by Sir William Johnson. The 1763 date on the image is incorrect, as Tryon County was not created until 1772. It is made of cut stone with a brick chimney on each end of the building.