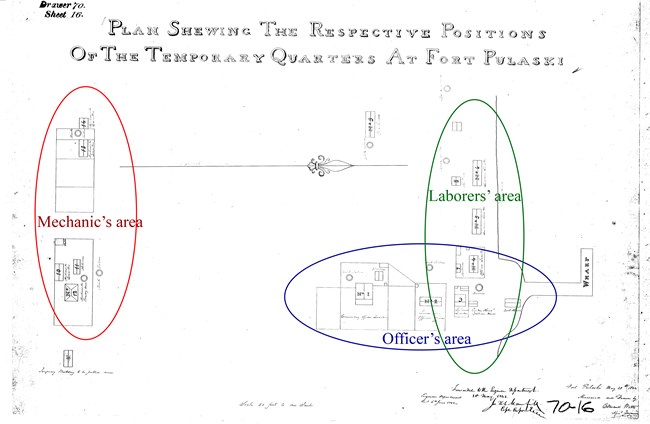

NPS/FOPU Archives Brick by Brick: The People Who Built Fort PulaskiFort Pulaski has guarded the entrance to the Savannah River for nearly 200 years. It is most famous for its 30-hour battle during the Civil War. However, Fort Pulaski only exists because of the civilian workers who built it. The Workers’ Village is the place where the people who built, maintained, and garrisoned Fort Pulaski lived. Occupied in varying degrees from 1829 until an 1881 hurricane destroyed every building on the island except the fort itself, the Workers’ Village is a crucial but under-examined part of Cockspur Island’s history. The Workers’ Village had three main clusters of buildings and was constructed in a way that divided workers. This is seen in the physical landscape as well as the material culture found through archeology. The officers’ houses, customs house, workshops, and laborers’ quarters (occupied by white and enslaved laborers) were situated on the northern part of Cockspur Island, around where Battery Hambright is today. The laborers' quarters were within sight of the officers’ and overseers, perhaps to exert more control over workers. The mechanics’ quarters, boarding house, and kitchen were grouped closest to the fort, adjacent to the modern-day parking lot. Mechanics refers to craftspeople such as masons, carpenters, and blacksmiths. The third grouping of buildings were built on the south coast of the island, but little is known about these because the area is difficult to access. This third section is not on the map above, which shows most of the Workers’ Village as it looked in 1842. The tiny circles show the locations of cisterns, which collected rainwater. The small, un-named buildings next to some of the quarters are privies (toilets). Types of Workers in the VillageEnslaved and free laborers created the ditch and dike system that keeps Cockspur Island mostly dry and allowed for Fort Pulaski to be built. They also transported materials around the island, worked in offices, helped on boats, cooked, and assisted the masons and other mechanics. These laborers were referred to as “unskilled” because they did not perform the supposedly more technical jobs of masonry and carpentry. However, the work they did, like building the ditch and dike system, required a tremendous amount of engineering knowledge and understanding of local tides. Many enslaved peoples on Cockspur Island had this knowledge due to their experience growing rice in Africa and from their forced labor on local rice plantations. The other main category of workers were the “skilled” laborers called mechanics. These laborers consisted of carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons, almost all of whom were white. There were a few enslaved Black masons and carpenters in the Workers’ Village, and their enslavers were paid less than the white masons and carpenters, demonstrating one of the many ways racial inequalities created a divide in the workforce and society. Overall, the “skilled” white workers made about twice as much as their “unskilled” counterparts, even as the “skilled” laborers relied on the “unskilled” labor to succeed in their work. Corps of Engineers officers were in charge of the construction site. They had their own kitchens and cisterns, a privilege of their higher status while they directed the construction. Other crucial jobs on Cockspur Island included boatmen, bakers, and cooks. The boatmen were responsible for moving supply ships between Savannah and Cockspur Island. One professional baker was employed on Cockspur Island during the 1830s. He supplied the bread for the workers during this period. Cooks made all the other meals. While the job of cook does not appear in Cockspur Island records until the 1870s, documents indicate that the laborers were cooking in the 1840s. This could mean that the laborers switched off cooking duties instead of having a dedicated chef. The cooks in the 1870s were all African American women, showing their general confinement to low-paying, service-type professions.

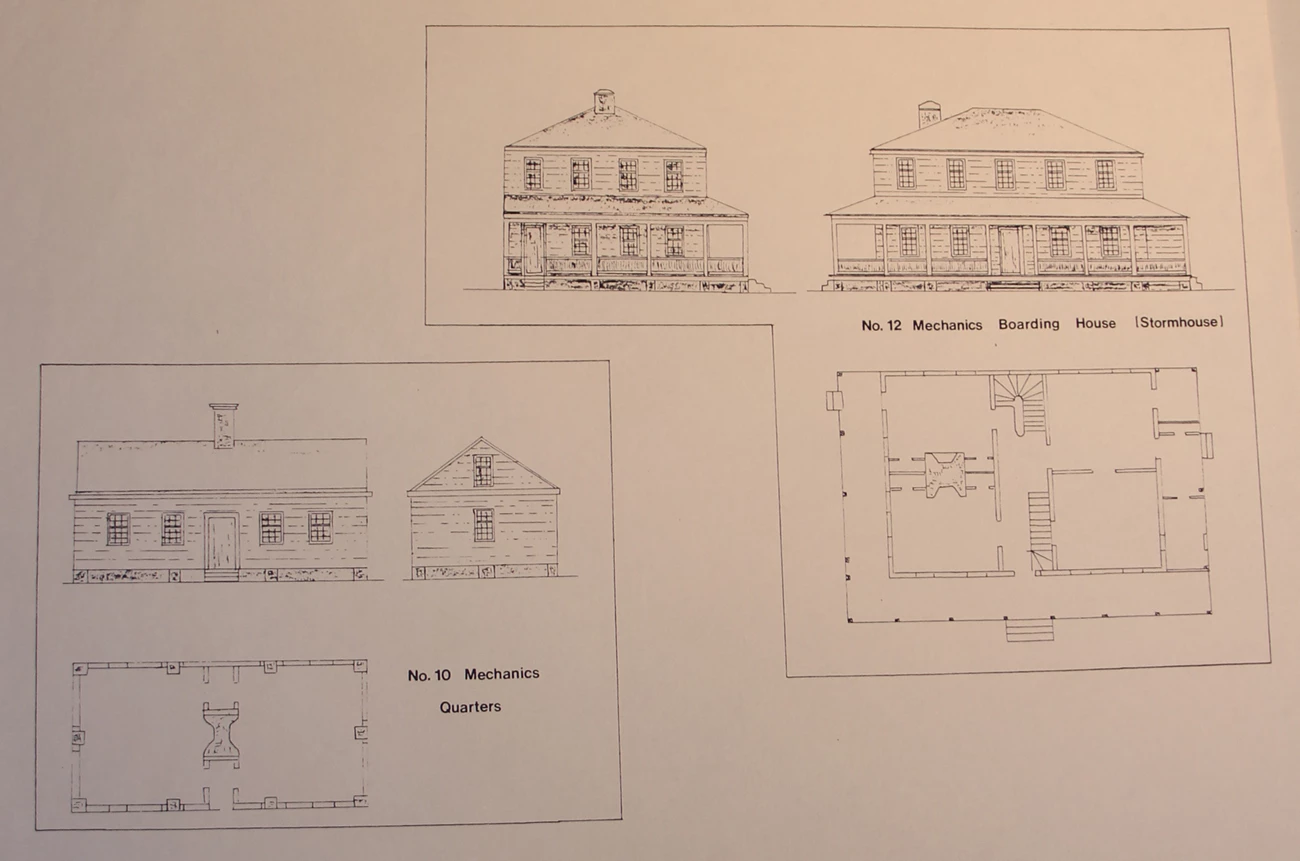

NPS/FOPU Archives Life in the Workers' VillageConstruction on Fort Pulaski and the Workers’ Village began in 1829. Though the Workers’ Village was originally intended to be temporary accommodations for the workers, intermittent lapses in funding ballooned Fort Pulaski’s construction to 17 years. During the height of construction, there were hundreds of workers on Cockspur Island including mechanics, free and enslaved laborers, officers, boatmen, and more. The Corps of Engineers often rented enslaved workers from local plantations throughout the construction period. Local runaway ads are evidence that some of these laborers tried to self-emancipate while on Cockspur Island.Life on Cockspur Island during the construction years was difficult. The work was incredibly hard and dangerous, the living quarters were not built for comfort, and workers were isolated from their families and other communities for extended periods of time. The weather was not ideal with high temperatures, humidity, and storms. Disease and sickness were common. From the completion of Fort Pulaski in 1847 until the Confederates took the fort in 1861, only a few workers remained on Cockspur Island to maintain the fort. Life on the island was relatively quiet during this period, except in September of 1854 when a massive hurricane battered Cockspur Island, damaging most of the buildings in the Workers’ Village. Fortunately, everyone on the island survived, taking refuge in the two-story Mechanics’ Boarding House (also known as the Storm House). During the Civil War era, the Workers’ Village transformed to fulfill several functions. The officer’s quarters in the Workers’ Village also functioned as a hospital during the war. The laborers’ quarters were also most likely used to house laborers or soldiers. Confederates forced approximately 300 enslaved workers to repair the ditch and dike system on Cockspur Island, in preparation of battle. These African American laborers likely lived in the Workers’ Village. An additional 55 free Black men volunteered their service to the Confederates in preparing the fort for battle. They arrived in June and July 1861, and were put to work cleaning cisterns and other general work. Many of them were mechanics with a variety of skills. This was a strategic move which guaranteed a job and income during the uncertain time. It also protected them against accusations of Union or abolitionist sympathies, which were very dangerous to have and could risk the safety of themselves and their families. These men may have been housed in laborers’ quarter or mechanics quarters.

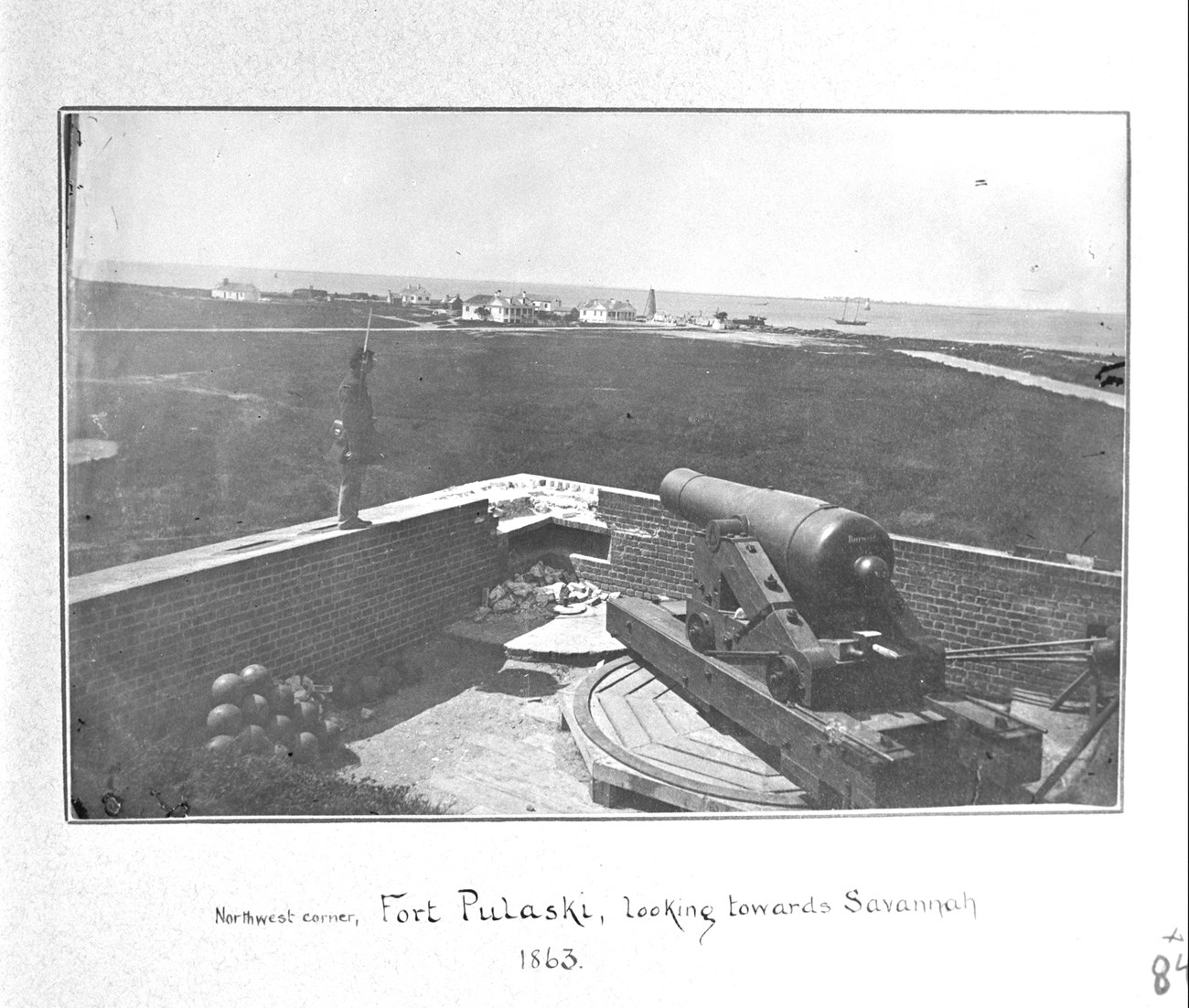

NPS/FOPU Archives Curiously, there appears to be a collection of pitched tents at the photo’s top right. The people living in these tents are likely either enlisted men or laborers who were maintaining Fort Pulaski and its ditch and dike system. According to the 1842 map, one of the laborers’ quarters should have been near that spot. Archeologists excavated the area and found evidence that a laborers’ quarter was present but was demolished before the Civil War.

NPS/Matera

NPS/FOPU Archives The difference, in terms of function, between the Mechanics’ Boarding House and the mechanics’ quarters, and why the Workers’ Village had both, is unclear. Boarding houses typically provided a room, three meals, and housekeeping services. Quarters, by contrast, only provided a place to sleep. One hypothesis is that the boarding house may have allowed wealthier or higher-paid mechanics to pay for their own private room, while also receiving higher quality meals. The boardinghouse may have thus functioned as a further class distinction on Cockspur Island. It is telling that the laborers did not have a boardinghouse as well, perhaps signifying their lower pay and status.

NPS

NPS/Seifert End of Workers’ VillageBetween 1869 and 1873, Cockspur Island had a large population of close to 200 people. A garrison was stationed at Fort Pulaski to enact improvements and upgrades to the fort. Enlisted men and non-commissioned officers lived in the “barracks,” which are probably the casemates inside the fort. They also lived in buildings outside the fort. The officers lived in the Workers’ Village officer’s quarters and other quarters with their wives and children, as well as African American cooks. African Americans farmers also lived on the island during this time, but it is not known where.After 1873, Fort Pulaski closed, having become obsolete due to advancements in rifled artillery despite the completed upgrades. By 1880, the island’s residents were its multiple lighthouse keepers and their families as well as Dr. J.P. Huger, the widowed, 60-year-old Quarantine Officer. Ordnance Sergeant John Martus was present with his family; his son George was also an assistant lighthouse keeper. Charles Poland, Lighthouse Keeper, had his wife Ellen with him. Lighthouse Keeper Thaddeus Morel lived with his wife Eliza, their daughter Josephine, and his sister Virginia. The Morels were the only African American family on the island in 1880. The younger Martus girls (Mary and Florence) and Josephine Morel (ages 14, 12, and 10 respectively) attended school somehow, probably tutored by their parents. Finally, John Grant, a 33-year-old Massachusetts native was the Fort Pulaski Keeper. The Workers’ Village continued to fall into disarray until 1881, when a massive hurricane demolished every building on the island except for Fort Pulaski. The island’s residents survived by taking refuge in the fort’s spiral stairwells. The history of the Workers’ Village ends there, but its importance lives on. There is no Fort Pulaski without the Workers’ Village. It provided workers a place to eat, sleep, and live their lives. Its importance to the history of Cockspur Island and to telling the stories of people who have since been forgotten cannot be understated. Next Section: The Benefits of Archeology |

Last updated: February 12, 2024