|

From the early morning hours on September 14, Fort McHenry had withstood a sustained attack by the British fleet, commanded by Admiral Cochrane. Despite attempts to fire back, the British ships were just out of range of the Fort’s cannons, and so by 11:00 a.m., General Armistead gave orders to slow things down to save ammunition. For the next two hours the British bombs and rockets kept up the firing on the fort with little effective fire returned by the fort.

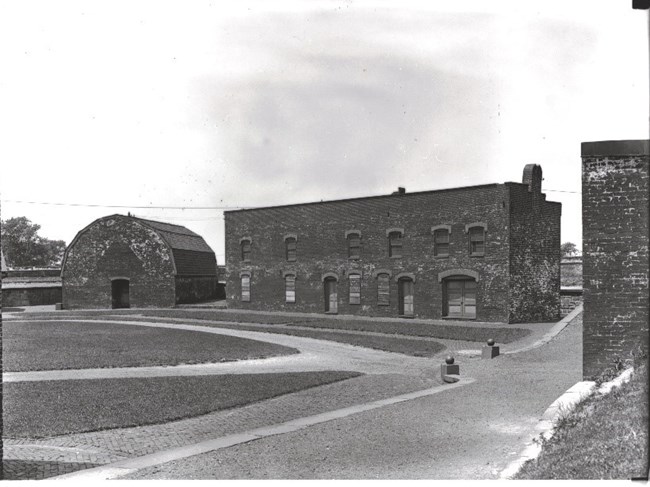

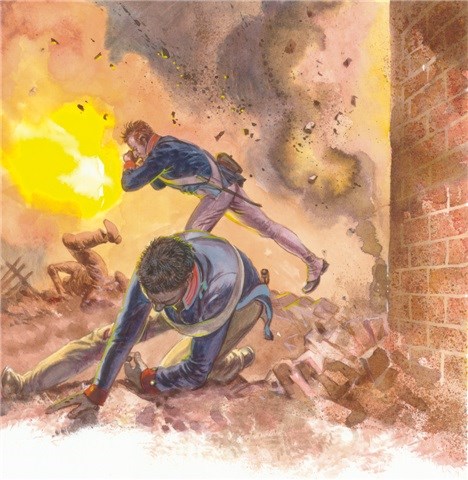

NPS The Tide Begins to TurnOne bomb achieved a direct hit on the fort’s powder magazine. The bomb glanced off the arch shaped roof, leaving a hole and caving in a portion of the ceiling of the powder room, which contained close to 200 barrels of powder. Had the bomb gone into the magazine it would have destroyed the fort with a catastrophic explosion. The only person who knew the powder magazine was not bombproof was Armistead. Not wanting to press his luck, he ordered the powder barrels removed from the magazine and distributed along the outer of the walls of the fort. One soldier, tired and needing to rest a minute, sat down on one of the powder barrels before realizing that was not a good idea.

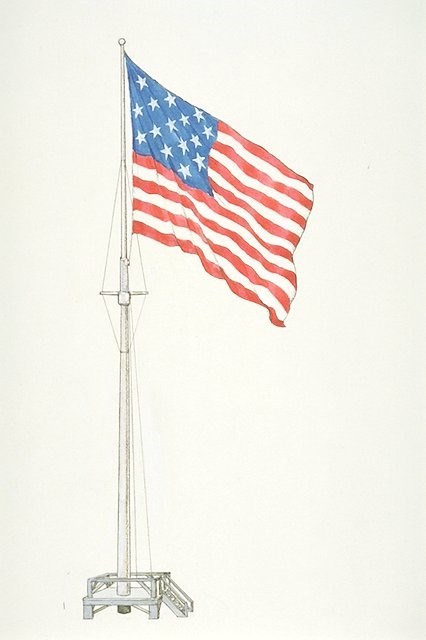

Excerpt from "In Full Glory Reflected" The bomb ships were only about 102 feet from bow to stern. When the mortars were fired the force of the recoil sent the ship downward into the water two feet. To keep the ships steady while firing, each bomb ship had anchors at the bow and stern. As the ships came closer to the fort, Armistead ordered the men back to their guns. The ships moved from two miles to within a mile and half or closer, which now put them within range of the fort’s cannons. Armistead waited until the bomb ships dropped their anchors, and then ordered all the guns in the fort and outer battery to open fire. For the next hour the fort’s cannon kept a brisk fire at the British ships. The VOLCANO and DEVASTATION were hit several times, with water pouring into the DEVASTATION. The rocket ship was also hit several times. From his command ship, Cochrane could see the damage that the fort’s guns were inflicting on his ships, and sent signals ordering them to move back out of range from Fort McHenry. The captain of the EREBUS either didn’t see the signal or chose to ignore it, so Cochrane ordered other ships to tow the rocket ship out of the forts range. With light rain and clouds during the rest of the afternoon, the British ships kept up a heavy rate of fire while the fort’s guns returned fire intermittently. During the bombardment the residents of Baltimore city, many on their rooftops or watching from the top floor windows, could see and hear the explosions and feel the earth shake as each bomb burst over the fort. During the midafternoon Cochrane received a note from Brooke and Cockburn, sent earlier that morning, asking for the Navy’s support for the planned land attack on the defenses at Hampstead Hill. Cochrane could not be sure if his earlier message, saying he would be unable to support the army’s attack, had been received. He felt he had to come up with a plan in case Brooke still attacked Hampstead Hill. His plan was to stage an attack on the smaller forts along the Ferry Branch of the Patapsco, to the west of Fort McHenry, and possibly an attack on the fort itself. This would act as a diversion and hopefully draw defenders from Hampstead Hill to reinforce the forts, allowing Brooke’s army to break through the defenses and take the city. The attack was to begin at 2:00 a.m. Cochrane signaled officers to meet on the temporary command ship SURPRIZE to help formulate a plan. Around 8:00 p.m., shortly before Cochrane’s meeting, the message he had sent earlier informing Brooke and Cockburn that the navy would not be able to assist in the attack on the defenses of Hampstead Hill, was received. They both were surprised, since they had been counting on the support of Cochrane’s guns to reduce the defenses and take the city. Brooke, encouraged by Cockburn, still hoped to take Baltimore. Consulting with his officers at a council of war, some still supported an attack on Baltimore. But due to the strength of the town’s defenses, and without naval support, Brooke believed it would be too costly to continue the attack. After consulting with his officers, they decided the movement back to the ships would begin in the morning. Meanwhile, Cochrane’s new plan of attack along the Ferry Branch would be led by Captain Charlie Napier. About midnight, under heavy rain to hide the attack from the defenders, about 1,000 men in 20 barges of various sizes began rowing towards the Ferry Branch. Some of the barges had small bow guns, others had rockets, and one was armed with an 18-pounder cannon. To support Napier’s attack, Cochrane ordered the EREBUS and bomb ships to begin a sustained fire on the fort. Rowing with muffled oars towards the Ferry Branch, half of the barges took a wrong turn and headed into the Northeast Branch, straight towards the sunken ships and the boats manned by the Chesapeake Flotilla. Realizing their mistake, the barges returned to the fleet before they could be discovered by the defenders. About 30 minutes after starting, Napier noticed that half of his force was missing. He waited for a while, then with only nine barges and 128 men, he continued past Fort McHenry into the Ferry Branch. About 1:00 a.m. on September 14, the blue light of a flare was fired into the night sky. It was a signal to the British soldiers at the defenses on Hampstead Hill that a diversion was under way. Since it was raining heavily, the British east of the city might not have seen it. At Battery Babcock, the six-gun earthwork about a mile and half west of Fort McHenry, Sailing Master John Webster was trying to get a quick nap during an interlude in the firing from the British ships. An experienced sailor, Webster thought he heard some strange sounds over the bombardment of the fort and a heavy thunderstorm,. Listening closer, he recognized the sounds of muffled oars. Looking out across the Ferry Branch, probably with the help of lightning, he saw shapes of small boats in the darkness. Alerting his men, and with the guns already loaded, Webster gave the order to open fire. The first shot sent an 18-pound cannon ball into one of the barges. Hearing the discharges of Babcock’s guns and the screams of the men in the barges, the sailors in Fort Covington, a half mile upstream, opened fire. Fort Lookout, another mile inland from both Babcock and Covington, also began firing. The defenders at Fort McHenry added their firepower against the barges as well. The barges returned fire. Napier had been told the British attack on the defenses of Hampstead Hill would begin about 2:00 a.m. Despite the heavy fire on his barges, he was waiting for some sign that Brooke’s attack had started. Napier waited nearly an hour to see if the British Army was attacking Baltimore. With no sign of an attack seen to the east of the city, he ordered a return to the fleet. The British soldiers who faced the entrenchments surrounding Baltimore were watching Napier’s attack and the supporting fire of the bomb ships. The sight and sounds of the battle and the storm were later described by some of the British soldiers as thrilling and terrifying. By 3:00 a.m., realizing there would be no naval support, Brooke sent out the order for his men to march back to the fleet. To their surprise, and with mixed emotions, the men retreated from Baltimore. As Napier’s barges returned to the fleet, they remained within range of the guns at Fort McHenry for close to an hour. One barge was hit, throwing the men into the Patapsco as it overturned. Men in the fort could hear a British voice say, “By God they’ll blow us out of the water!” The guns of Forts McHenry, Babcock, and Covington fired on Napier’s barges for the next two hours. Bodies of British sailors would be found floating in the river for the next two weeks. Once the barges were out of range of the American guns, the firing stopped. The British ships still fired occasionally. By 4:00 a.m., all the barges had returned to their ships.

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center The British RetreatBy now Admiral Cochrane had decided it was time to leave Baltimore and the Patapsco River. For close to twenty hours the British navy had kept up what should have been an overwhelming bombardment of Fort McHenry without achieving any results. The British army had failed to capture Baltimore, and its commander, Major General Robert Ross, had been killed. |

Last updated: August 27, 2023