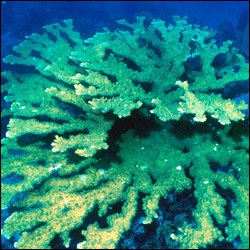

Paige Gill, FKNMS Named for its resemblance to elk antlers, elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) is structurally complex with many large, thick branches. As with staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), the dominant reproduction mode of elkhorn coral is asexual fragmentation. New colonies form when branches break off of a colony and reattach themselves to the substrate. In addition, sexual reproduction through spawning each year in August or September also occurs. Individual colonies are concurrently male and female — a condition called simultaneous hermaphrodites. Although millions of eggs and sperm, called gametes, are released, few coral larvae survive to settle and grow into new colonies. Because so little sexual reproduction takes place, genetic diversity may be very low in remnant populations. Low genetic diversity makes coral populations more susceptible to being decimated by disease. Like staghorn coral, elkhorn coral has been listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Colonies of elkhorn coral are relatively fast growing, with branch length increasing about 2 to 4 inches per year. Colonies reach maximum size in about 10 to 12 years. Coral age can be determined by counting coral growth rings the same way that tree rings are counted to determine tree age. Elkhorn colonies typically grow in water depths of less than 20 feet but may be present down to a depth of about 65 feet. The species ranges geographically from its northern limit in Biscayne National Park to its southern limit in Venezuela. Large, continuous elkhorn thickets once extended along the front side of most coral reefs and supported a diverse assemblage of other invertebrates and fish. Once the most common coral in the Caribbean and known as the “giant redwoods of the reef,” today it is more common to see rubble fields made up of dead elkhorn coral and only a few isolated living colonies.

E. Weil, NOAA Since 1980, elkhorn populations have collapsed throughout their range from disease outbreaks, with losses compounded locally by hurricanes, predation, bleaching, elevated temperatures, and damage from sedimentation. In 1996, researchers documented the first case of white pox disease in a reef off the shore of Key West. Within four years after the white pox was found, the population of elkhorn coral in that reef had decreased by 82 percent. Further research determined that the cause of white pox is a jellybean-shaped bacterium called Serratioa marcescens that is common in human intestines but is not known to be typical in healthy reefs. In addition, other coral diseases discovered since the mid-1990s have been traced to bacteria found in human waste. The rapidly increasing trend in coral die-offs may be partially explained by the growing populations of people living along and visiting tropical coasts and the resulting greater volumes of human waste spilling into coastal waters. Coral is destroyed by white pox disease more quickly in late summer, when seawater is the warmest. Global warming may also be a factor in the loss of coral because it lengthens the disease season. Although recovery from physical disturbances such as hurricanes can be relatively rapid thanks to asexual fragmentation, the process does not occur in cases of disease or bleaching, making recovery very difficult. Research continues today in an effort to understand why intestinal bacteria attack coral and how water temperature and other factors contribute to coral diseases. |

Last updated: July 16, 2015