In Their Own WordsThe National Park Service is dedicated to telling all Americans' stories. Some history hurts and some heals, but all of it can surprise and inspire us. Castillo de San Marcos National Monument is working closely with the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, the Comanche Nation, and the Caddo Nation to bring Tribal members to Fort Marion for annual gatherings.

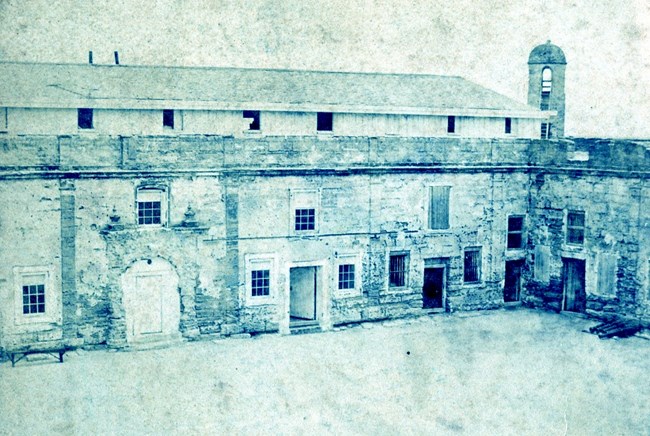

Imprisoned 1875 - 1878As western expansion increased in the mid 1800's, tensions and violence between the Native Americans and white settlers began to escalate. These rising tensions were the origins of the Red River War fought in the year 1874. This war essentially ended the traditional way of life for the people of the Great Plains, and at the conclusion of this war, many Native Americans in the southwestern territories had been forced onto reservations. One such reservation was Fort Sill in current day Oklahoma. It was from this reservation that 74 prisoners, mostly male warriors, were chosen for confinement. Many were survivors of the brutal Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. They came from five different tribes; there were 33 Cheyenne, 27 Kiowa, 11 Comanche, 2 Arapaho, and 1 Caddo. Included among the prisoners were 10 Mexicans who had been assimilated into these tribes. Conditions at Fort MarionConditions at the fort were bleak. Many of the prisoners were uncertain whether their lives were in danger or just how long the imprisonment would last. They wore chains and shackles, were kept under lock and key, and were confined to the casemates (rooms) and courtyard. The gundeck was blockaded and access was only allowed when accompanied by a guard. The prisoners slept on the room floors, most of which were dirt; albeit some wooden floors were added later to make the conditions more sanitary. Still, disease was a constant concern, and the continuous presence of guards from the St. Francis Barracks made the Native Americans incredibly anxious.The commanding officer at St. Francis Barracks was initially responsible for the care of the Native Americans in St. Augustine, but after six months of incarceration, Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt was given command of the prisoners at Fort Marion. Under his direction conditions at the fort would drastically change.

Pratt Arrives

Richard Henry Pratt was a Lieutenant in the 10th Cavalry. He was assigned to duty in the District of the Indian Territory, comprising most of present-day Oklahoma, as early as 1867. In 1875, Pratt went east to Fort Marion and served as the jailer at the fort until the prisoners were released to the Indian Bureau in 1878. Pratt was the driving force behind the 1879 founding of the Carlisle Industrial School in Carlisle Pennsylvania, and served as the school's superintendent until his dismissal in 1904. When Pratt was given charge of the prisoners, he initiated many changes. First, all the chains and shackles were removed, the blockade to the gundeck was taken down, the guards from St. Francis Barracks were relieved, and the rooms ceased to be used as living facilities. The prisoners were given wood to build housing accommodations on the north gundeck, a structure described as being 100 feet long and the width of the gundeck, with rough board bunks on each side. Pratt also organized a guard unit composed of the prisoners themselves and he furnished these guards with army uniforms and weapons. For the duration of their confinement, the prisoners carried out daily drills, performed all guard duties, were subject to daily inspections, engaged in morning exercise routines, went camping on Anastasia Island, learned how to sail and fish, learned agricultural skills, and made periodic trips to Fort Matanzas. Pratt also organized or approved many special events at the fort or in St. Augustine, such as a dance at the fort, the production of stage performances for profit, a buffalo chase in downtown St. Augustine, and a circus inside the old fort.

Education & Industry

Although Pratt bettered the Plains prisoners’ living conditions; they were still prisoners. This life was very different from their ones back home. During the imprisonment, the young men received a western education. They learned how to speak and write in English along with other elementary level western skills. Many of the casemates were converted into classrooms, and lessons were conducted during the morning hours. The teachers were mostly local women who volunteered their time. These women included Sarah Mather, Anna Pratt, Rebecca Perrit, Nannie Burt, Julia and Laura Gibbs, and Amy Carruthers. In addition to receiving an education, the prisoners were encouraged to earn money by producing items to sell and engaging in jobs in town. Bows and arrows, polished alligator teeth, canes, and paper toys were all sold for profit. Popular souvenir items at the time were sea beans.Sea beans could be collected on Anastasia island, and those found here are called MacKay beans, which are seeds found in the tropics and deposited on the coastlines of Florida. These beans were collected, polished, and sold to tourists. In addition, the prisoners periodically had odd jobs such as clearing land, and one prisoner worked at a local rail depot.

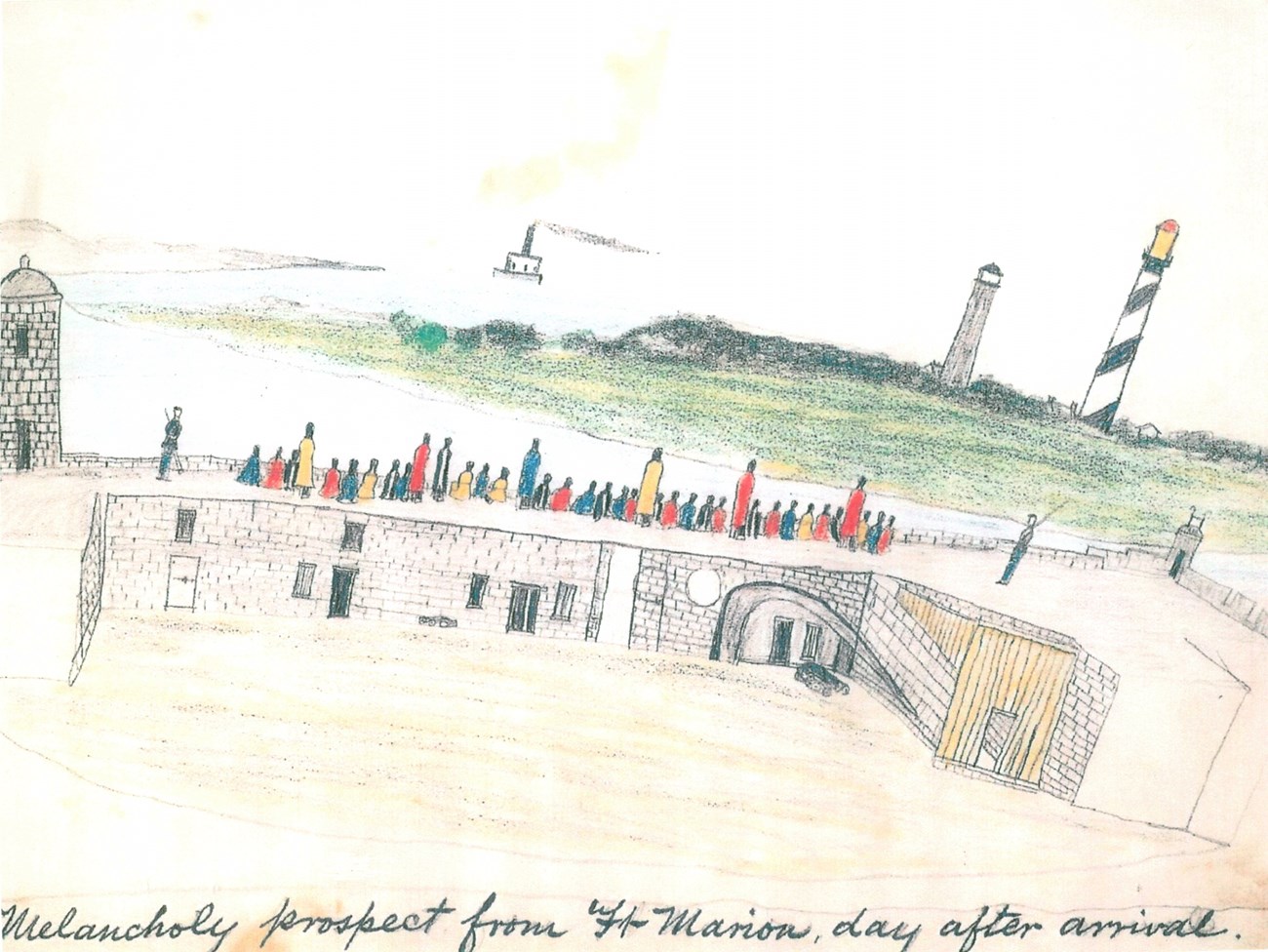

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution Ledger DrawingsMany of the young men confined at Fort Marion created artwork known as ledger drawings. This term refers to the artists' use of paper, usually from an accountant's ledger book, as opposed to the more traditional buffalo hide. As buffalo were systematically hunted to near-extinction by the U.S. Army and European settlers on the Great Plains, paper became a more common medium for Native artwork. Ledger drawings were created with lead pencils, ink, colored pencils, oil pastels, and watercolors. Today, modern Native American artists continue this tradition through modern ledger art. Many examples of ledger drawings from this period of imprisonment still exist today. The surviving sketches from Fort Marion indicate the prisoners had access to blank or partly used ledgers, army rosters, day books, memorandums books, and various pieces of paper. These works illustrate a close connection between ledger drawings and traditional Native American hide painting. Common characteristics of ledger drawings include faces usually in profile and near and far objects generally placed on top of one another to show distance. The focus of this artwork is typically not on shading, backgrounds, or color variations, but rather on documenting situations and stories. Common themes included scenes of life on the plains, the journey to Florida, and the prisoners' experiences at the fort. Life after Fort MarionIn 1878, the prisoners at Fort Marion were released to the care of the Indian Bureau.Twenty-two formerly incarcerated expressed a desire to stay in the east and continue their education. Pratt then made arrangements for these men to have their education funded by white citizens. Pratt convinced the superintendent of the Hampton School, a school in Virginia started for freed slaves after the Civil War, to accept seventeen of these men as students. The remaining five went to live with families in the northeast. However, most prisoners made their way back west.

A Painful LegacyPratt worked at the fort to assimilate the prisoners. He instructed them to give up their cultural identity and accept a new way of life. As evidenced by the small number of the original seventy-two incarcerated that chose to stay in the east and assimilate into the white ways Pratt preached, most prisoners were less than eager to change their identity. One such Plains prisoner, in an act of resistance, chose to etch a traditional Kiowa Sundance Camp scene on the walls of the prison. Despite their best efforts, the U.S. government could never fully erase the culture and traditions of these Native peoples. |

Last updated: September 19, 2025