|

While fault lines, volcanoes, and mountain ranges are more commonly associated with geologic activity, barrier islands are exceptionally active landforms. In fact, barrier islands are among the most dynamic geologic features in the world. These islands are in constant flux as winds, waves, and currents move sand and reshape the land.

Barrier Islands BasicsBarrier islands are migratory, slowly moving towards the mainland in a process called barrier island migration or island rollover. During storms, strong winds create a surge of water that can wash over the island. This storm surge picks up and carries sand from the ocean beach to the marshes and beach on the sound side of the island. Here, the sand spreads out, creating blooms of sand called overwash fans. These deposits may be quite thick, raising the marshes higher out of the water and extending them further out into the sound. This overwash is essential to the marshes and other sound side habitats because it is the primary source of new sand deposits in that area. Over 85% of the sand found on the beaches of Cape Lookout National Seashore is composed of quartz. Dark strips of sand, composed of biotite or magnetite as well as other minerals, can occasionally be found among the tan colored quartz sand. This heavy mineral sand is typically deposited on our beaches by storms which carry the sand from the mid-ocean rift valley.

Storms, Tides, and WindsBarrier islands were so named because of their ability to absorb the energy of a storm, effectively creating a barrier between the storm and the mainland. The impact of hurricanes and other storms on barrier islands can be significant. Storm-force winds and waves can cut inlets, destroy dunes, and push sand across the island from the ocean side beach to the sound side marshes. Ordinary winds and waves can have similar, though much less dramatic, effects. In low-lying areas, high tide waters can wash over top of the island, pushing sediment across the island to the sound side. In addition, stronger waves and increased wind and storms erode the beaches faster in the winter while softer summer waves allow the beach to grow. This results in a winter beach with a shorter, steeper beach face and a summer beach with a longer, more gently sloping beach face. This difference is part of the reason off-road vehicles are not permitted in the park during the winter: there is little or no room between the high tide and the dune line and the more quickly eroding winter beach cannot recover as easily.

Core and Shackleford BanksThere are two major sections of the barrier island chain within Cape Lookout National Seashore: Core Banks and Shackleford Banks. Shackleford Banks extends from Beaufort Inlet on the western side to Barden Inlet on the eastern side. Core Banks extends from the point of Cape Lookout and Barden Inlet up to Ocracoke Inlet, across from Ocracoke Village and Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The ocean beach on Shackleford Banks faces southwest while the ocean beaches on Core Banks are southeast facing. Because the prevailing winds are typically northeasterly or southwesterly, sand is often blown across Shackleford Banks from the ocean side to the sound side and blown up or down the beaches of Core Banks. This has allowed plants to trap more sand on Shackleford Banks, resulting in significantly larger dunes on this island than on any of the islands composing Core Banks. A maritime forest has thrived on Shackleford Banks because these large dunes protect the trees from the damaging effects of salt spray.

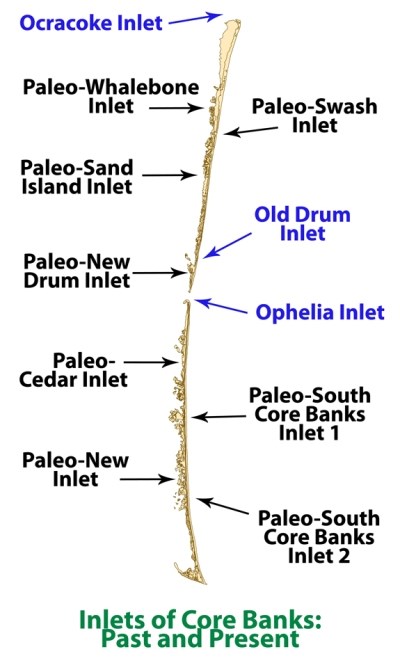

Inlets of Core BanksThere are generally two large islands which compose Core Banks. These islands are called North Core Banks, also known as Portsmouth Island, and South Core Banks. These islands have been separated more or less constantly since 1899 by an inlet located between mile 18 and mile 24 of the national seashore. At times, additional inlets open, separating Core Banks into three or more islands. Some of the inlets which have appeared along Core Banks are Whalebone Inlet, Swash Inlet, Sand Island Inlet, Old Drum Inlet, New Drum Inlet, Ophelia Inlet, Cedar Inlet, and New Inlet. In order to distinguish them from existing inlets, geologists typically call historical inlets paleo-inlets (for example, Whalebone Inlet is called Paleo-Whalebone Inlet). These inlets are often highly dynamic: opening, widening, shallowing, closing, and reopening. For example, Old Drum Inlet opened around 1899 just south of mile 18. This inlet closed naturally in 1910, but was reopened by storm surge from a hurricane in the fall of 1933. Old Drum Inlet attempted to reclose and, in order to maintain this channel to the ocean, the inlet was periodically dredged from 1939 until 1952. Old Drum Inlet closed again in January of 1971. New Drum Inlet was artificially opened that same year near mile marker 22. Old Drum Inlet was reopened in 1999 by Hurricane Dennis. In 2005, Hurricane Ophelia deposited sand in Old Drum Inlet, which closed shortly afterwards, and opened an inlet near mile 24, named Ophelia Inlet. Ophelia Banks-marked by Ophelia Inlet to the south and New Drum Inlet to the north-migrated northwards, eventually closing New Drum Inlet. Hurricane Irene, which made landfall near Cape Lookout in September 2011, reopened New Drum and OId Drum Inlets. This storm also widened Ophelia Inlet. Additional ResourcesGeology Fieldnotes: Cape Lookout National Seashore -- maps, photos, and links to research. Coastal Geology in our National Parks -- an introduction to coastal geology including coastal hazards, climate change, and human impacts. Effect of Storms on Barrier Island Dynamics, Core Banks, Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina, 1960−2001 (pdf, 3.8 MB) by Stanley R. Riggs and Dorothea V. Ames Past, Present, and Future Inlets of the Outer Banks Barrier Islands, North Carolina (pdf, 2.9 MB) by David J. Mallinson, Stephen J. Culver, Stanley R. Riggs, J.P. Walsh, Dorothea Ames, and Curtis W. Smith Dynamics of Beaches and Barrier Islands by Phil Stoffer and Paula Messina Beach Basics excerpts from How to Read a North Carolina Beach by Orrin H. Pilkey |

Last updated: October 20, 2023