Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

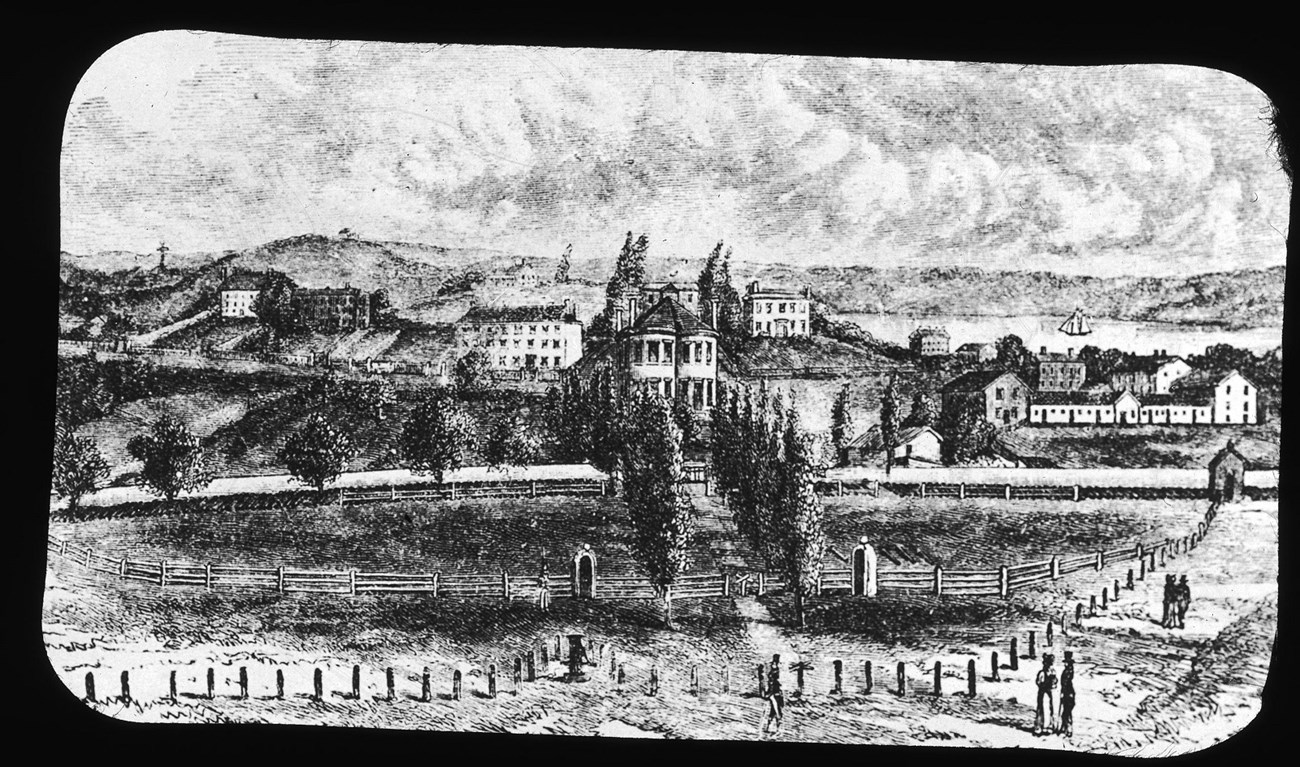

Charlestown Navy Yard: Commandant's House

Boston Public Library, Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion

A Neighborhood on a Hill

Set upon the highest point in the Charlestown Navy Yard, the Commandant's House stands apart from the cranes, shipways, railways, and industrial buildings that define much of the Navy Yard's landscape. It sits at the center of a small neighborhood of sorts, a small community of US Navy and Marine personnel that not only worked, but also lived, in the Navy Yard.

Completed in 1805, the original architect of the Commandant's House remains a mystery. But the design goal was clear: to build a house "on a substantial scale" as a reflection of the Commandant's importance and expectation as a host. To this end, the house was divided into two worlds. Upstairs, the house was a private living space for the Commandant and his family. Downstairs on the first floor, it was a public ceremonial space for dances, formal luncheons, dinners, and other gatherings.

Willard F. Smith photo, Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 9195

The Commandant's Role

The Commandant served as the highest officer at the Charlestown Navy Yard. He directed the yard as a military and industrial center. Yet, part of those duties included acting as a diplomat for the Navy and opening up the Commandant's House to various stakeholders.

While shops at the Charlestown Navy Yard contributed material things to the construction of a new warship or maintenance of the fleet, the Commandant's House produced a less tangible product in its tradition and prestige.

Important Guests

Guests included Presidents James Monroe and Andrew Johnson as well as other political leaders. Dignitaries from abroad who traveled to Boston also visited the Navy Yard. This included the return of Revolutionary War general and hero, the Marquis de Lafayette, to the United States in 1824. Greeted with a 15-gun salute, he dined in the Commandant's House and met the Yard's officers and their wives.

Over the years, the Commandant's House was used to host a variety of gatherings, from charity events run by the wives of Navy Yard officers to meetings with special guests, such as the pilot Charles Lindbergh. The Commandant even offered the space as a neutral zone during a labor dispute between the Teamsters and Longshoremen unions in the 1970s.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 9185-681.

Maintenance Woes

Since its construction, the Commandant's House has undergone a series of renovations and it required constant maintenance. When William Bainbridge took command of the Yard in 1812, he complained that his new quarters was "built on too expensive a scale, [and] very inconvenient as to its construction..." though it was only seven years old, he worried the house would not "stand for many years, without great repairs."

The soft bricks used in the original construction of the house did a poor job keeping moisture out of the building. In 1812, the house was painted for the first time in an attempt to waterproof the structure, a process repeated multiple times over the next 110 years. Though the Charlestown Navy Yard itself performed constant maintenance of US Navy ships, the maintenance of many buildings, including the Commandant's House, was not always seen as a priority. The US Navy often denied the Commandant's requests for funds to repair the house.

Ironically, while the Navy Department pushed back on requests for items such as paint and wallpaper, they approved the installation of running water and central heating in the 1830s. Running water was a luxury at the time and central heating was practically unheard of. Further improvements included a dumbwaiter and electric doorbell. The Navy also later installed a small refrigerator similar in size to one that could be found in a hotel. It seemed that the US Navy prioritized entertaining important guests at the Navy Yard, while overlooking the long-term living arrangements.

In 1922, Rear Admiral Henry Wiley requested funds to remove the paint and return the house to its original appearance. Despite a new sealing process promising to reduce the long-term costs of painting the building, the Navy Department was initially resistant. Wiley eventually prevailed and the house remains unpainted today.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 9286-4560.

The Green House and Garden

While the Commandant's House aimed to be more welcoming than industrial, that does not mean that the house failed to produce anything tangible. Among the Commandant's staff were gardeners who tended to the grounds, garden, and greenhouse. In these spaces, they grew both decorative flowers and vegetables for the Commandant's table.

Completed under Commander Nicholson in the 1840s, the greenhouse allowed the staff to prepare fresh floral arrangements year-round. These floral arrangements served as decorations for dances, dinners, and luncheons held for naval officers and dignitaries who visited the Navy Yard and the Commandant's House.

Some two decades later, however, it was realized that the Navy Department had never officially authorized the greenhouse. In a continuation of the constant battle between the Navy Department and the Commandant for funding, in 1864 the Navy ordered the Commandant of the Yard at the time, Silas Stringham, to dismantle the greenhouse and sell off the structure, glass, pots, and even the plants grown inside.

A replacement greenhouse was attached to Building 21—the stable—which served the Commandant until 1963. At this time, the Navy Department dismantled the greenhouse and the Navy Yard turned to a private florist to fill its continuing need for decorative flowers.

Commanding the Landscape

After more than two centuries, the Commandant's House still stands upon the slight rise of the Yard's landscape, looking out over the Yard, USS Constitution, Boston, and the Harbor. It represents a less tangible, less utilitarian side of the Charlestown Navy Yard: a place of public ceremony and private life in the Yard.

Sources

Albee, Peggy A., The Commandant's House Historical Structure Report, Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, April 1990.

Bearss, Edwin C.. Historic Resource Study: Charlestown Navy Yard, 1800-1842, Volume I and Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, October, 1984.

Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Vol 1-3. Boston, MA: Division of Cultural Resources Boston National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010.

Micholet, Margaret, Public Place, Private Home: A Social History of the Commandant’s House at the Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, April 1986.