Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

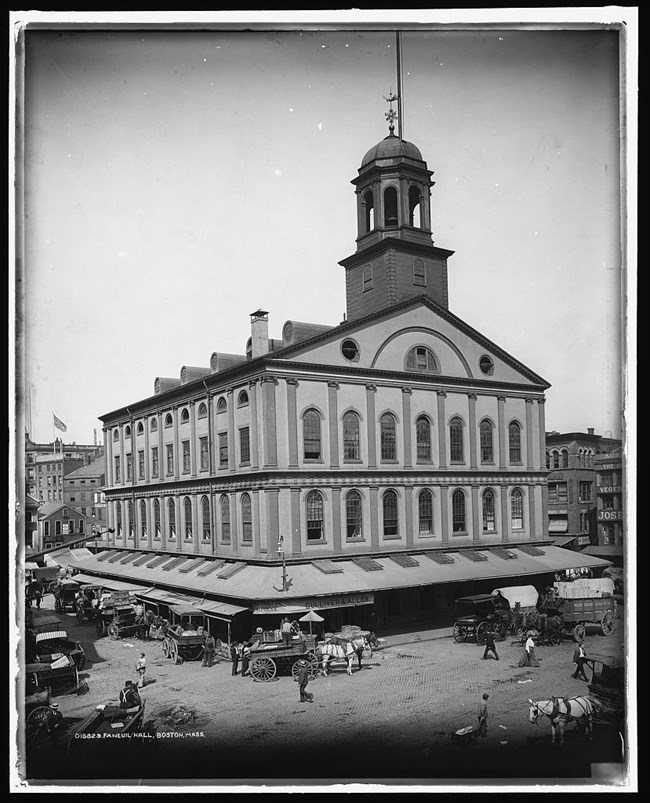

When The Rising Came to Boston

On 14 January, 1917, Faneuil Hall, the revered "Cradle of Liberty" to patriots of the American Revolution, witnessed a speech that ironically, in its description of British military atrocities, would not have seemed dissimilar from the speeches delivered in the Great Hall in the 1770s. Yet this speech perhaps would have sent the heads of those stoic Yankee Protestants spinning, as it was delivered to an estimated 3,000 people by an Irish-Catholic Feminist, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington.

Boston Public Library

For all Boston's current associations with the trappings of the Irish diaspora, colonial Boston was a virulently anti-Catholic and by extension, anti-Irish town. While mobs burned papal effigies during the debaucheries of Pope's Night, Catholics in Boston dutifully assembled at Faneuil Hall in 1746 simply to assure their wary neighbors that they had no divided loyalties between the colonial government and the pontiff in Rome. This apparent meekness slowly altered with the sea-change demographic shift of the 1800s as waves of Irish immigrants began to edge their way in to the public and political sphere of Boston.

As new American citizens, inspired in part by the earlier struggle that drove Britain out of the Thirteen Colonies, many Boston Irish cast their eyes back to their small island, then still under British domination, and began to wonder about independence. Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, saw the most concentrated effort in a century in Ireland to resist Britain in what became known as the Easter Rising. Doomed from the start, Irish nationalists clashed with British troops in Dublin for five days before eventually being overwhelmed. Naturally, Boston Irish sympathetic to the rebels were interested in a first-hand account of the battle and its aftermath, which Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington was tragically capable of telling.

Photograph by Bain News Service. From the collections at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2005023452/)

Hanna, born in County Cork in 1877, was a well-known nationalist, suffragette, and labor organizer. Her husband, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, was an author, journalist, pacifistic, and nationalist as well. When the two married they both agreed to share a hyphenated last name, an action particularly radical in the early 1900s.

Although Francis opposed Irish recruitment in World War I (for which he was jailed), he was not a participant in the Rising. In fact, during the urban battle, Francis did meet with one of the Rising's leaders, James Connolly (who spoke at Faneuil Hall in 1902) to seek aid in preventing widespread looting in Dublin.

On April 25, as British troops fought to regain control of the city, Francis was seized and taken hostage by a British military patrol. At Faneuil Hall, Hanna described what happened the next day:

My husband walked across the [Portobello] barracks yard and without warning was shot in the back ...Dublin Castle ordered the removal of the bricks [where the bullets impacted] in order to wipe out evidence of the shooting. It ordered the burial of the bodies [two other newspaper editors were also executed in a likewise manner] at night...although I lived within ten minutes' walk of the barracks and must have heard the volley that killed him, I was never informed to this day of his murder. Every scrap of evidence I have been able to get together was forced from the reluctant authorities.[1]

Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company. From the collections of the Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016796306/)

As reported by The Sacred Heart Review in 1917, "Mrs. Skeffington showed remarkable self-control as she related the tragic happenings." As to why she had decided to cross the Atlantic to speak in Boston, Hanna explained, "I know it would have been my husband's wish, and the wish of all those brave men that I am proud to have called friends, that their life message would not be in vain, and that every act of British militarism as I have known it should be known to you here under the free republic of America."[2]

Ironically, the initial Rising had limited public support, especially considering the resultant destruction of large parts of Dublin and civilian casualties, but the summary execution of the Rising's leaders, and others, such as Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, permanently soured far more people on British rule. In the wake of the later Irish War of Independence, Ireland achieved Free State status and eventually (with the exception of six counties in Northern Ireland) became the Republic of Ireland. In 1960, on the eve of election night, John F. Kennedy gave his last campaign speech in Faneuil Hall (he had first spoke there publicly in 1946), demonstrating just how far the Irish in Boston had come.

Footnotes

[1] "Mrs. Skeffington At Faneuil Hall," The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 57, Number 6, 20 January 1917, page 3. Boston College Libraries.

[2] "Mrs. Skeffington At Faneuil Hall," The Sacred Heart Review.

Sources:

"Casualties Sheehy Skeffington." 1916. National Library of Ireland. Accessed February 2025. Digital Exhibit.

"Mrs. Skeffington At Faneuil Hall." The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 57, Number 6. 20 January 1917, page 3. Boston College Libraries.

"Revealing History: Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington." National Library of Ireland. 2022, accessed February 2025. Revealing History.