Last updated: September 27, 2018

Article

Bat Population Monitoring at Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River

NPS photo

Why is the park interested in bats?

Bats are an important part of ecosystems and food webs. Though some species of bats feed on fruit, seeds, or pollen, the species that live in the northeastern United States are insectivores. They consume huge numbers of insects every night, filling a unique ecosystem role as nocturnal insect predators. Unfortunately, a new disease called white-nose syndrome is affecting bats across the United States. To better protect bats, biologists are studying how local bat populations are changing.

Research Highlights

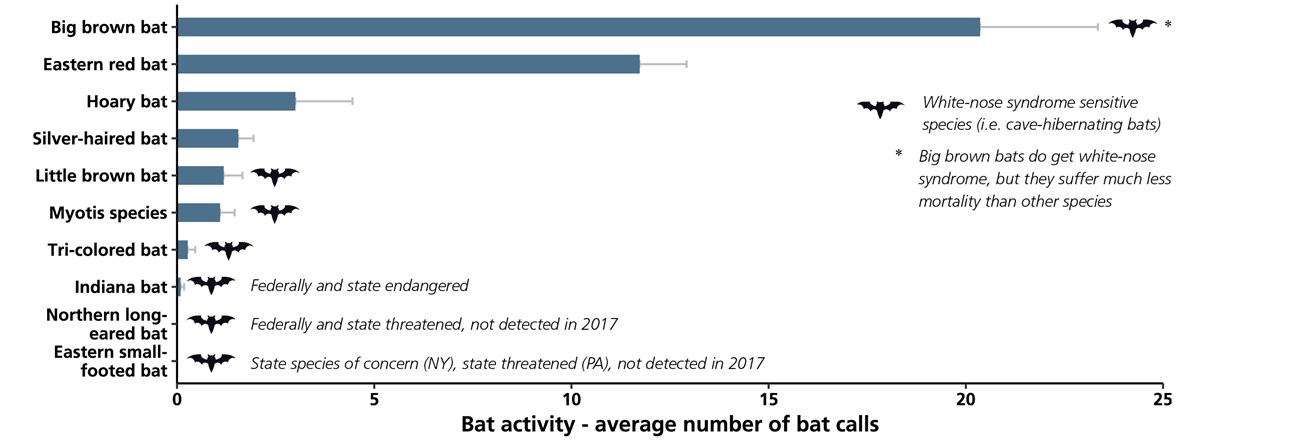

- Nine species of bats have been documented in the park, including two federally threatened or endangered species.

- White-nose syndrome has dramatically reduced the populations of some bats.

- Little brown bats—a species now rare across the Northeast—can still be found in unusually large colonies in the park.

- Conservation of roosting habitat is one important action being taken by park staff.

How do biologists study bats? What have they learned about bats in the park?

Biologists use a variety of techniques to study bats. Special nets (i.e. mist nets) can be used to catch bats at specific sites in the park. After capturing a bat, biologists can identify its species, determine the sex of the animal, evaluate its age, and examine the wings for damage from the white-nose fungus.

Biologists have other creative ways of studying these amazing animals. Bats use echolocation to navigate and catch insect prey during the night. People can’t hear these bat calls, but biologists use special microphones, called acoustic detectors, to record the sounds. By analyzing the bat calls, biologists can identify which bat species are present in an area. At Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River, park biologists attach these acoustic detectors to vehicles and then drive specific routes to record bat activity (see Figure 1 below).

Biologists also monitor bats at birthing locations called maternity roosts—these are the places where bats raise their young. Biologists can watch a roost in the evening and count bats as they emerge. These “emergence counts” help biologists estimate how healthy a bat population is from year to year.

Since 2008, the park has been cooperating with East Stroudsburg University to study bat populations. To date, nine species of bats have been documented. These include the federally endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) and the federally threatened northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis). Once common, the northern long-eared bat is now rare due to white-nose syndrome. The most frequently detected bat in the park’s acoustic detector surveys is the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus). This is not surprising since big brown bats have been less affected by white-nose syndrome than other hibernating bat species.

It is important to note that the park supports some large colonies of little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus)—potentially some of the largest colonies in Pennsylvania. These groups of bats spend summer days living in various man-made structures in the park. Park biologists monitor these colonies closely, using emergence counts to document the number of bats each year.

NPS photo

What is the park doing to protect bats?

Biologists continue to learn about bats and are working to conserve bat habitat in the park. For example, in places were roosting habitat isn’t adequate, roosting structures (“bat boxes”) are being installed. Park staff are also working with private landowners to identify important colonies of bats and to find ways to protect those colonies. Bat research efforts are ongoing. White-nose syndrome is an extraordinarily dangerous threat to bats—sadly, some species may ultimately disappear from the region.

Want to learn more?

For more information:

Contact National Park Service Biologist Jessica Newbern.

Download a printable pdf of this article.