Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

True to the Public Trust: James Lynch

Wikimedia Commons - NatalieMaynor, Jackson, Mississippi

“My object at this time is to chronicle the unparalleled heroism and courage exhibited by the 54th Mass. Regiment, on last Saturday evening…”[1]

Reverend James D. Lynch wrote these words in a letter to the Christian Recorder from St. Helena Island, South Carolina on July 21, 1863, after witnessing the remaining members of the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Regiment return to camp following their assault on Fort Wagner. A twenty-four year old reverend, Lynch interacted with the 54th during their time on St. Helena, leading worship services for the men before the battle and praying for the wounded upon their return. Over the following ten years, Lynch became an influential clergymen, orator, and one of the most important Republican politicians in Reconstruction era Mississippi.

Rev. James D. Lynch, born free in 1839 in Baltimore, Maryland, travelled to St. Helena Island as a missionary of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. His free-born father, minister Benjamin Lynch, purchased the freedom of his enslaved mother, Lucy Brown, sometime before James’ birth.[2] After Lynch attended elementary school at his local AME church,[3] his parents sent him north to New Hampshire to attend Kimball Union Academy, one of the few integrated schools in the country.[4] Financial trouble forced Lynch to leave school after two years. He spent time teaching in Brooklyn, New York before committing to a career as a minister. The AME church sent him west to Indiana to begin preaching.[5]

Around 1860, Lynch returned to Baltimore to complete his training as a minister, and he continued to preach there during the first years of the Civil War. After the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, a group of AME ministers, including Lynch, sailed south seeking to build new churches and bring new members into the faith.[6] Two years prior, federal troops captured the Sea Islands off the South Carolina coast, freeing close to 8,000 enslaved people. The Federal Government began building schools and other infrastructure for the newly freed people.[7] Lynch and his fellow clergy saw an opportunity to bring churches to these communities. This missionary work brought Lynch to St. Helena Island, where his path intersected with the 54th Regiment.

On July 5, Rev. Lynch preached to the men of the 54th at their camp. He wrote to the Christian Recorder: “Col. Shaw…ordered out his regiment in full uniform, with arms, as if preparing for review, formed them into a hollow square in front of the stand, where they stood, officers and soldiers, listening to the words of eternal life.” Lynch described Shaw as “a learned scholar, accomplished gentleman, skillful officer, and brave soldier.”[8] After the Assault on Fort Wagner, Lynch gave a detailed account of the battle to the Recorder:

“The commanding general … concluded to take Fort Wagner at the point of the bayonet. This duty was given to several regiments, among whom was the 54th Mass. who led the column. They were exposed to a raking fire that thinned their ranks most rapidly, and stepping over the dead bodies of their comrades…drove the rebels from their guns and the fort. Unable to hold it, the 54th retreated… a shattered, scarred, and wounded band of men, covered with blood and glory.”[9]

He also commented on the fate of those captured by the enemy, stating:

“The sufferings which the wounded passed through who fell into the hands of the rebels, is enough to excite sympathy in the breasts of even fiends, while the atrocities which the rebels committed upon them is enough to make Satan blush.”[10]

Lynch published the names of the wounded and wrote of the state of the regiment:

“they were soon made as comfortable in the hospitals as circumstances would permit. I have visited them every one, and spoken words of cheer, and asked God to sustain them. I never saw men so cheerful in suffering in my life. It seems as though every man had counted the cost and fought and bled from the deepest inwrought convictions of duty. Only two weeks ago I preached to his regiment while they were in camp at Land's End, St. Helena. How changed the appearance. Then they stood in full dress, one thousand strong, leaning on their arms in hollow square. Their gallant Colonel and Adjutant near my side. Now two-fifths of them lie beneath the sod, and nearly a fifth helpless upon their beds. Col. Shaw sleeps in death.”[11]

Over the next two years, Lynch traveled across South Carolina and Georgia as federal forces captured more territory and more enslaved people became free. Only 25 years old, Lynch established himself as a leading elder of the church in the region.[12] In January of 1865, Lynch and a group of Black clergy met with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and General William Sherman in Savannah to advocate for federal assistance for the newly freed people in Georgia.[13] After the war, Lynch relocated to Philadelphia to serve as editor of the Christian Recorder. In 1867, Lynch and his family set off for Mississippi to continue their work as missionaries. While a minister in Mississippi, Lynch’s influence extended beyond the church as he became one of the most important Republican politicians in the state.

Federal troops remained in the states of the former Confederacy for years following the end of the Civil War, a period called Reconstruction. States adopted new constitutions, free from slavery, as part of their reintegration into the United States. The federal presence in these states allowed for Black men to take part in the political process and prevented the pro-slavery Whites from regaining power. This allowed Lynch to involve himself in local politics once settled in Mississippi.

In 1868, he attended the state’s constitutional convention.[14] He supported a new constitution that extended voting rights to Black men and created a framework to establish public schools across the state.[15] Newly enfranchised Black voters in Mississippi helped Lynch win the election for Secretary of State in 1869. He became the first Black person in the state’s history to serve in that office.[16] After re-election in 1871, Lynch attempted to run for Congress but the election turned ugly when a woman accused him of attempted rape. Though the case went to trial, it ended in a same-day acquittal when it became clear that political opponents had set Lynch up in order to damage his reputation.[17] Despite the acquittal, he failed to secure the nomination.[18]

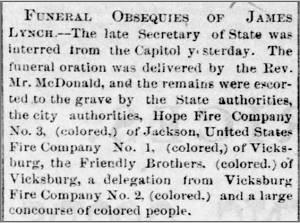

The Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi)

Lynch remained the Secretary of State of Mississippi until December 1872, when he died at age 33 from Bright’s disease. Described in his obituary as a “master of a fervid oratory, which swayed the passions of the African masses,” Lynch “despised the ignoble herd of the baser sort of white men by whom he was surrounded.”[19] After his funeral, a large procession of Black firemen and Black citizens followed his body to Greenwood Cemetery in Jackson, a primarily White cemetery, for burial.[20]

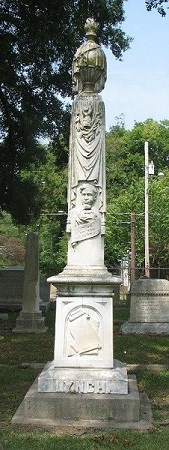

Find-A-Grave, NatalieMaynor, Jackson, Mississippi

Two years later and after much debate, the Mississippi State Senate voted 16 to 15 along partisan lines to spend $1000 on a monument to Lynch at his gravesite.[21] The monument features an engraving of his face, probably the only surviving likeness of Lynch, and the phrase “True to the Public Trust,”[22] a fitting epitaph for a man who accomplished so much in such a short life.

Unfortunately, many of his political accomplishments did not last. In the years after his death, the “baser sort of white men” Lynch despised regained control of Mississippi. Federal troops withdrew from the state in 1877, removing protections Black citizens needed to participate in the political process. In 1890, another convention ratified a new constitution built upon White supremacy. This document codified the system of poll taxes and literacy tests that disenfranchised African Americans in the state for years to come.[23] To add insult to injury, in 1900, the state legislature voted to remove Lynch’s monument and exhume his remains so that they could be placed in a segregated Black cemetery.[24] Fortunately, they never carried out this plan. Today, this monument serves both as a sad reminder of an unrealized promising future for postbellum Mississippi and as a powerful testament to Lynch’s extraordinary work as a minister, orator, wartime missionary, and politician.

Footnotes

[1] James Lynch, “Beaufort, S.C. Correspondence,” The Christian Recorder, August 22, 1863, 1.

[2] Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era [Two Volumes]. United Kingdom: Greenwood Press, 2006, 387.

[3] H. Scott Wolfe, “The Idol of the Negroes,” Galena Historical Society, I 1999.

[4] Jane Fiedler, On the Hilltop: Two Hundred Years at Kimball Union Academy 1813-2013, Nomad Press, 2012, 22.

[5] H. Scott Wolfe, “The Idol of the Negroes,” Galena Historical Society, I 1999.

[6] R.H. Cain, “The First Missionaries to the South from the AME Church,” The Christian Recorder, May 30, 1863, 1.

[7] Akiko Ochiai, "The Port Royal Experiment Revisited: Northern Visions of Reconstruction and the Land Question," The New England Quarterly 74, no. 1 (2001): 94, accessed July 16, 2020. doi:10.2307/3185461.

[8] James Lynch, “Beaufort, S.C. Correspondence,” The Christian Recorder, July 25, 1863, 1.

[9] James Lynch, “Beaufort, S.C. Correspondence,” The Christian Recorder, August 22, 1863, 1.

[10] Lynch, “Beaufort, S.C. Correspondence,” The Christian Recorder, August 22, 1863, 1.

[11] Lynch, “Beaufort, S.C. Correspondence,” The Christian Recorder, August 22, 1863, 1.

[12] H. Scott Wolfe, “The Idol of the Negroes,” Galena Historical Society, I 1999.

[13] E. D. Townsend, “The Freedmen of Georgia,” The Christian Recorder, February 18, 1865, 2.

[14] “Mississippi State Convention. Twentieth Day,” Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), January 30, 1868.

[15] “The 1868 Constitution of the State of Mississippi” Mississippi History Now http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/102/index.php?s=extra&id=269.

[16] “Special Order No. 277,” Hinds County Gazette, December 29, 1869.

[17] “From Jackson-Rev. Jim Lynch,” The American Citizen, August 3, 1872.

[18] Hinds County Gazette, September 11, 1872.

[19] “The Death of James Lynch,” Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), December 26, 1872, 2.

[20] “The Death of James Lynch,” Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Mississippi), December 26, 1872, 3.

[21] “Senate Bills,” Clarion-Ledger, (Jackson, Mississippi), April 9, 1874.

[22] Tom Rankin, “Grave of James D. Lynch, Greenwood Cemetery, Jackson, Mississippi, 2012,” Southern Spaces, https://southernspaces.org/2012/grave-james-d-lynch-greenwood-cemetery-jackson-mississippi-2012/.

[23] “The 1890 Constitution of the State of Mississippi,” Mississippi History Now, http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/103/index.php?s=extra&id=270.

[24] Laws of the State of Mississippi. United States: authority, 1900, 171.