Last updated: October 27, 2021

Article

Tiberius E. Julius

Boston served as one of the many destinations for African American southern migrants searching for new economic opportunities and fleeing discrimination during the Great Migration. This article highlights the journey of one of these southern migrants who settled in Boston, as shared on Boston National Historical Park’s Stories of the Great Migration page.

Tiberius E. Julius spent the first half of his life in Virginia, working as a blacksmith at a local shipyard. We do not know what sparked his decision to leave Virginia nor what path he took north. While parts of Julius' path remain a mystery, he began a new life in Boston, getting a job at the Charlestown Navy Yard and joining one of the local Black churches.

Explore the story-map below to learn about Tiberius E. Julius' Great Migration journey. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 189.

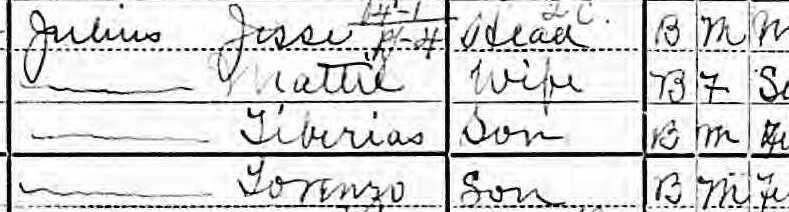

Image: United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1900, Chesapeake, Elizabeth City, Virginia, Enumeration District: 0005, FHL microfilm: 1241706, page 25.

[2] “1619 First African Landing,” Hampton VA, Hampton History Museum, accessed April, 2020, https://hampton.gov/3585/1619-Landing.; Andrew Lawler, “Fort Monroe’s Lasting Place in History,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 4, 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fort-monroes-lasting-place-in-history-25923793/.; “Give Me Liberty,” Hampton VA, Hampton History Museum, accessed April, 2020, https://hampton.gov/3184/Give-Me-Liberty.; Ibram X. Kendi, “The Hopefulness and Hopelessness of 1619: Marking the 400-year African American struggle to survive and to be free of racism,” The Atlantic, August 20, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/08/historical-significance-1619/596365/.; Michael Guasco, “The Misguided Focus on 1619 as the Beginning of Slavery in the U.S. Damages Our Understanding of American History,” Smithsonian Magazine, September 13, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/misguided-focus-1619-beginning-slavery-us-damages-our-understanding-american-history-180964873/.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1900, Chesapeake, Elizabeth City, Virginia, Enumeration District: 0005, FHL microfilm: 1241706, page 25.

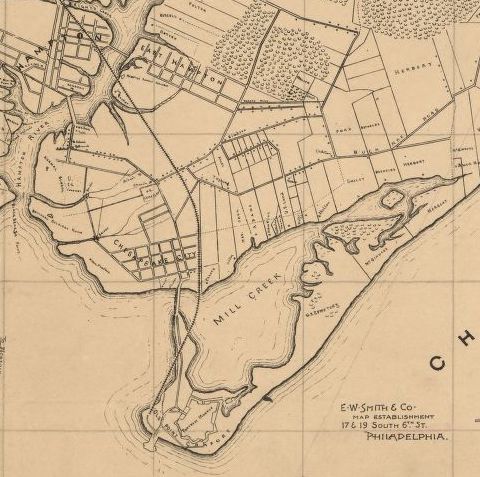

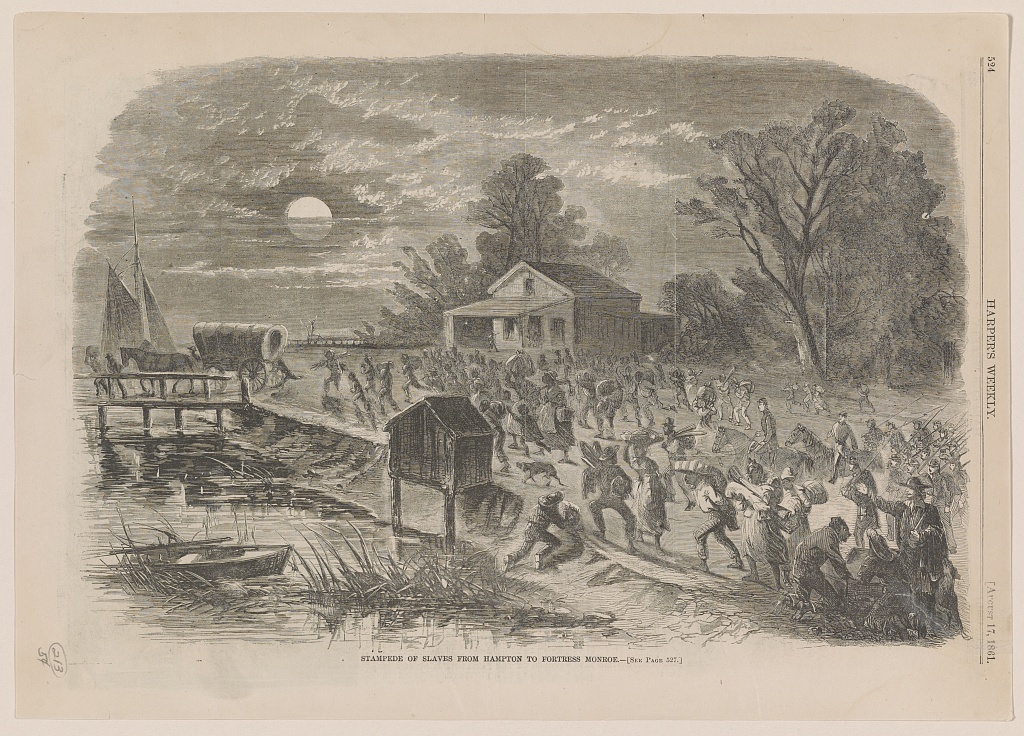

Image: Semple, E. A, Wm Ivy, C Hubbard, and E.W. Smith & Co. Map of Elizabeth City Co., Va.: from actual surveys by E.A. Semple, Wm. Ivy and C. Hubbard. Philadelphia: E. W. Smith and Co, 1902. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2011588010/.; Stampede of slaves from Hampton to Fortress Monroe. Fort Monroe Hampton United States Virginia, 1985. [? from a Print In1861] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92515012/.

[3] “African American Life,” The Old Dominion Land Company and the Development of the City of Newport News, Corporation of Newport News Virginia, accessed April, 2020, http://cdm15904.contentdm.oclc.org/ui/custom/default/collection/default/resources/custompages/odlcexhibit/index/african_american.html; Tiberius Julius entry, Newport News, Virginia City Directory, 1913 (Newport News, VA: Hill Directory Company, Inc., Publishers, 1913), 178.; William A. Fox, Downtown Newport News (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2010), 13, Google Books .

Image: Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Twenty-eighth St., Newport News, Va. Newport News Newport News. United States Virginia, ca. 1906. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016817807/.

[4] Fox, Downtown Newport News, 13.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1920, Newport News Ward 2, Newport News (Independent City), Virginia, Enumeration District: 100, Roll: T625_1899, page 9A.; Tiberius Julius, World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Registration State: Virginia; Registration County: Warwick; Roll: 1991375; Draft Board: 1.

Image: "Liberty launching day, Newport News Shipbuilding," Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company E.O. Smith, Archive Number: P0001.019/01-102#PS456, The Mariners' Museum and Park. https://catalogs.marinersmuseum.org/object/ARI87326.

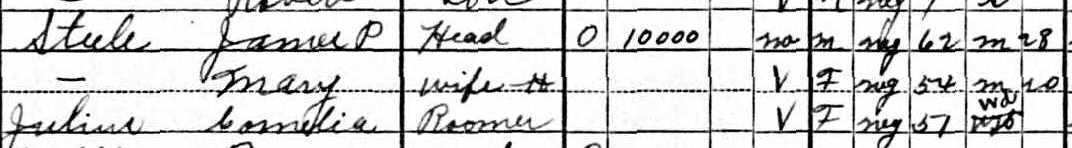

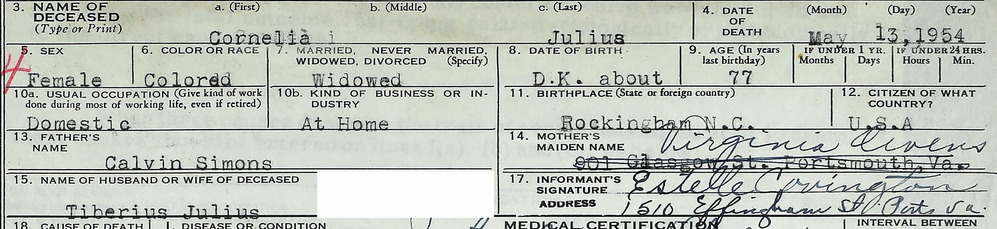

[5] Cornelia Julius Death Record, 1954, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia, Virginia Deaths, 1912-2014.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1930, Newport News, Newport News (Independent City), Virginia, Enumeration District: 0009, FHL microfilm: 2342203, page 9A.; Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns.

Image: United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1930, Newport News, Newport News (Independent City), Virginia; Enumeration District: 0009, FHL microfilm: 2342203, Page 9A; Cornelia Julius 1954 Death Record, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia; Virginia Deaths, 1912-2014.

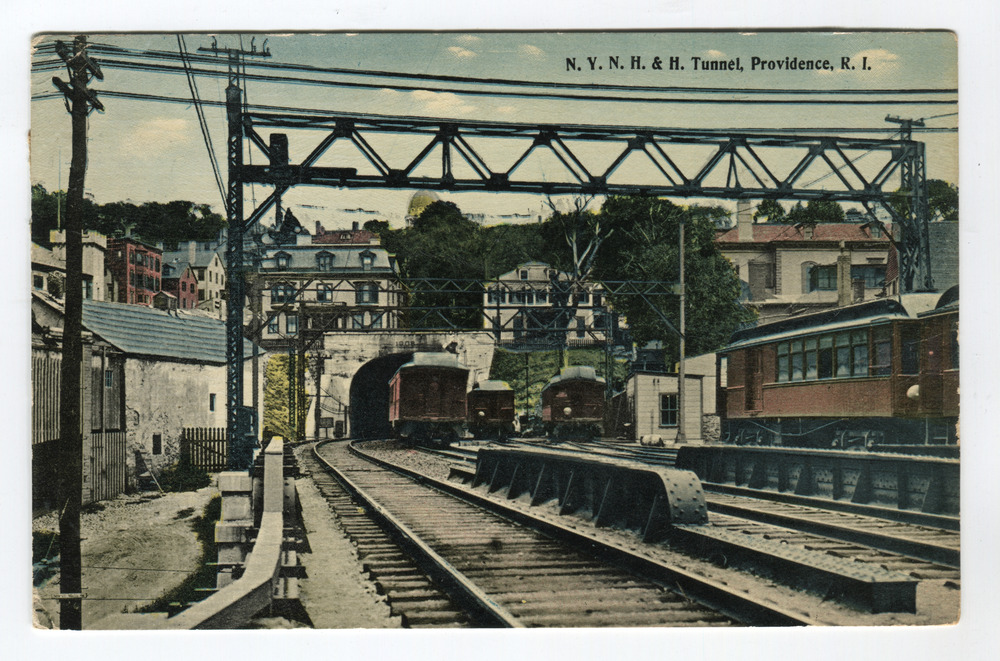

[6] Tiberius E. Julius entry, Providence City Directory, 1924 (Providence, Rhode Island: Sampson & Murdock Company, 1924), 496.; Subsequent entries also Sampson & Murdock Company: Julius entry, Providence City Directory, 1930, 878.; Julius entry, Providence City Directory, 1934, 567.

Image: "East Side Tunnel, Providence," postcard, 1913, published by Charles H. Seddon, Rhode Island Collection, Providence Public Library, https://www.provlibdigital.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A17035.

[7] Tiberius Julius, World War II Draft Cards (Fourth Registration) for the State of Massachusetts; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147; Series Number: M2090, The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri.; "United States Census, 1940," database with images, GenealogyBank (https://genealogybank.com/#), Tiberius Julius, Ward 9, Boston, Boston City, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States.

Image: "DD-455 USS Hambleton in Drydock after Torpedoed;" Administrative History of the First Naval District in World War II, 1946 - 1946; Record Group 181: Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, 1784 - 2000, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/7326759.

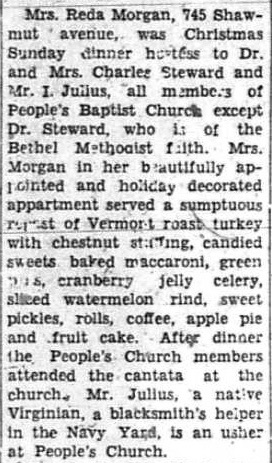

[8] “African Meeting House,” Boston African American National Historic Site, Massachusetts, accessed April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/amh.htm.; “City News” section, cropped image, Boston Guardian (Boston, MA), Dec. 30, 1944, 6.; Robert C. Hayden, Faith, Culture and Leadership: A History of the Black Church in Boston (Boston: Boston Branch NAACP and Robert C. Hayden, 1983), 6, 8.

Image: “City News” section, cropped image, Boston Guardian (Boston, MA), Dec. 30, 1944, 6.

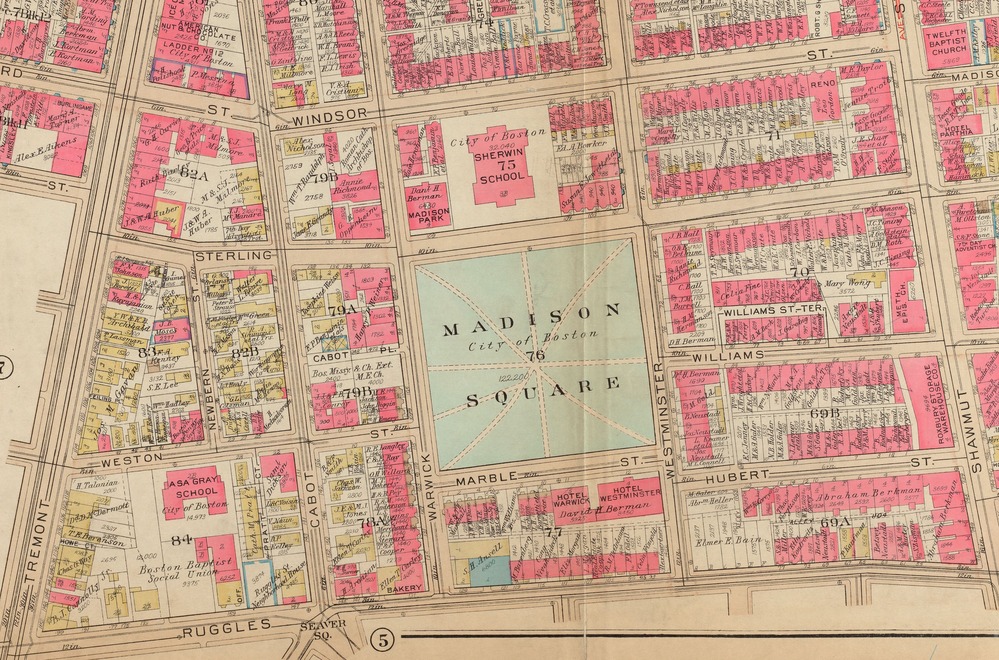

[9] Tiberius E. Julius entry, Boston City Directory, 1945 (Boston, Massachusetts: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1945), 888. Subsequent City Directories have the same publisher. Boston CIty Directory, 1946, 946.; Boston City Directory, 1947, 977.; Boston City Directory, 1948, 980.; Boston City Directory, 1951, 940.; Tiberius E. Julius Purchasing 36 Windsor Street, Deed, June 27, 1945, Julian D. Steele Collection, Armstrong Hemenway Foundation B Correspondence, Box 11, Folder 4, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Image: G.W. Bromley & Co., "Atlas of the city of Boston, Roxbury," Map, 1931, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:1257c361w.

[10] “Back Bay Crash Injures 5 Men,” The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), April 7, 1952, 10.; Tiberius E. Julius entry, Boston City Directory, 1951 (Boston, Massachusetts: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1951), 940. Subsequent City Directories have the same publisher. Boston City Directory, 1952, 1123.; Boston City Directory, 1954, 1125.; Boston City Directory, 1957, 1056; Walter Jennings, interviewed by Celeste Bernardo, Oral History, September 2, 2000, Boston National Historical Park, 11.

Image: "Berkeley Street at Stuart Street," photograph, ca. 1940, Record Identifier: 5000-009-1338, Public Works Department photograph collection (5000.009), Boston City Archives, https://cityofboston.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/digitalFile_676c8a19-045e-4643-a37b-46d1dd986e7e/.

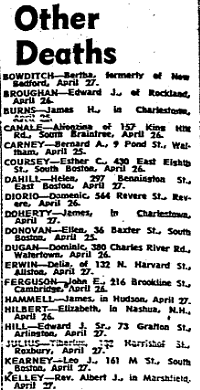

[11] “Other Deaths” section, cropped image, Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), Apr. 28, 19458, pg. 10 . Genealogy Bank.

Image: “Other Deaths” section, cropped image, Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), Apr. 28, 19458, pg. 10 . Genealogy Bank.