Subjects of the King and republican citizens were sometimes more than willing shift their allegiances, depending on which side offered the more favorable conditions.

"Their discontent for the British service & predilection for this country was a constant theme among the British officers.” –Major Thomas Melville, Commandant of Pittsfield Massachusetts Prison

Library of Congress

Major Thomas Melville (uncle of the novelist Herman Melville) was a well-to-do Republican living in the staunchly Republican town of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Initially placed in charge of housing new recruits, Major Melville proposed that he be given authority to merge the scattered prisoner-of-war camps and jails throughout New York and New England into a single, consolidated facility at Pittsfield. When the War Department approved his plan, Melville threw his energies into supervising the construction of a barracks, stockade, hospital and kitchen. Later, Melville would borrow $5,000 on his personal credit to keep the prison running.

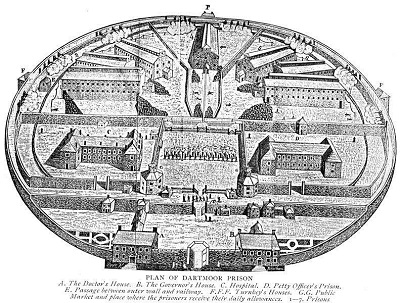

Those unfortunate enough to be captured in battle during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries often suffered miserable conditions in prisoner camps. During the War of Independence, some American prisoners of war found themselves confined on prison ships in New York Harbor, with filthy conditions and poor rations; thousands died of neglect. Americans taken prisoner during the War of 1812 fared little better. Britain’s Dartmoor prison packed 6,500 American soldiers alongside more than 8,000 French prisoners in notoriously poor conditions. When prison officials cut inmates’ rations, some American prisoners began gathering outside their allotted courtyard, and the inexperienced British guards fired on them. The Dartmoor Prison massacre left seven Americans dead and another 31 wounded.

Melville’s experiment in confining prisoners of war rejected those miserable traditions. Instead, Melville (who ultimately oversaw the incarceration of over 1,300 enlisted inmates), was as generous as possible with his charges. During their captivity, prisoners received permission to earn good wages on local farms and in Western Massachusetts’ flourishing textile mills. Captured British officers lived even better, boarding with local residents and eating so well that one complained of “getting the Gout” from his rich diet. During the day, incarcerated officers raced horses, fished, played games and read. At night they staged plays and caroused.

While most of the prisoners seemed fairly content with these conditions, at least one paroled British officer who returned to Canada expressed displeasure at the way Melville was using his captives to wage his own brand of warfare by benevolence. In a report to his superiors, the paroled officer warned that the “ruinous System of Temptation” and “general liberty given” by Melville’s generous treatment “throws out such a strong temptation [that]…not half…can reasonably be expected to return” home.

Indeed, Melville shrewdly saw the humane treatment of prisoners as one way to win the minds and hearts of opponents during wartime. Each instance of refusal by a British, Irish, or Canadian prisoner of war to repatriate amounted to a propaganda triumph for the Americans.

Melville appeared to understand better than most just how fluid and ambiguous national identity could be during the War of 1812. His prisoner “experiment” provided one illustration of how subjects and citizens sometimes shifted their allegiances, depending on which side offered the more favorable conditions.

Last updated: May 4, 2016