Last updated: January 8, 2023

Article

Theodore L. Bailey

Boston served as one of the many destinations for African American southern migrants searching for new economic opportunities and fleeing discrimination during the Great Migration. This article highlights the journey of one of these southern migrants who settled in Boston, as shared on Boston National Historical Park's Stories of the Great Migration page.

Born in a small town in Virginia, Theodore L. Bailey spent several years of his life moving to different towns looking for new opportunities before he arrived in Boston. In this city, he continued his search for employment, working in several different occupations, including as a blacksmith at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Explore the story-map below to learn about Theodore L. Bailey's Great Migration journey. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

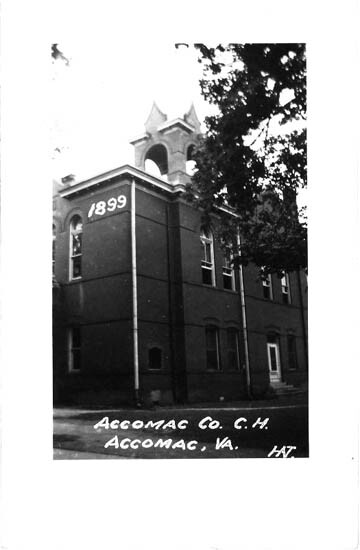

[1] “About the County,” Accomack County, Virginia, accessed March, 2020, https://www.co.accomack.va.us/about-us/about-the-county.; Theodore L. Bailey World War II Draft Card, The National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; World War II Draft Cards (Fourth Registration) for the State of Massachusetts; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147; Series Number: M2090.; U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 8 - Population of Incorporated Cities, Towns, Villages, and Boroughs in 1900, with Population for 1890,” Section 8: Cities, Towns, Villages, and Boroughs, Twelfth Census of the United States - 1900, Census Reports Volume 1 - Population 1, 477.

Image: “Accomack County Court House,” photograph, 1899, Penny Postcards from Virginia, USGenWeb Archives Website, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/accomack/postcards/ppcs-accomack.html.

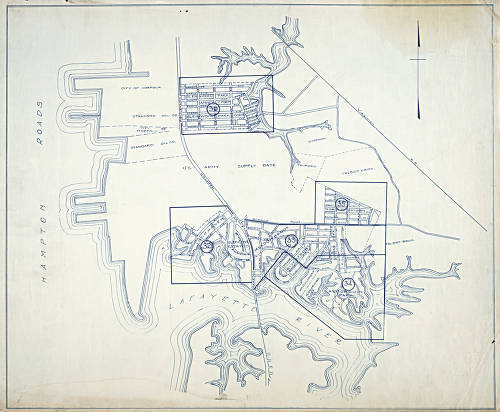

[2] Jaedda Armstrong, “What’s in a name: Titustown, Norfolk,” The Virginian Pilot (Virginia), Sept, 28, 2009, https://www.pilotonline.com/history/article_ebd685ca-9b9f-5de1-8216-833c71c2bfde.html.; Leon Everett Bailey World War II Draft Card, The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; Draft Registration Cards for Massachusetts, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 35; “Neighborhoods: Norfolk 1923 Annexation,” The City of Norfolk, accessed March, 2020, https://www.norfolk.gov/DocumentCenter/View/881/Norfolk-1923-Annexation-?bidId=.; Theodore Lee Bailey World War I Draft Card, Registration State: Virginia; Registration County: Norfolk; Roll: 1984910, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.; United States Census Bureau, Census Record, 1920, Boston Ward 7, Suffolk, Massachusetts, Enumeration District: 211, Roll: T625_732, Page 5B.;

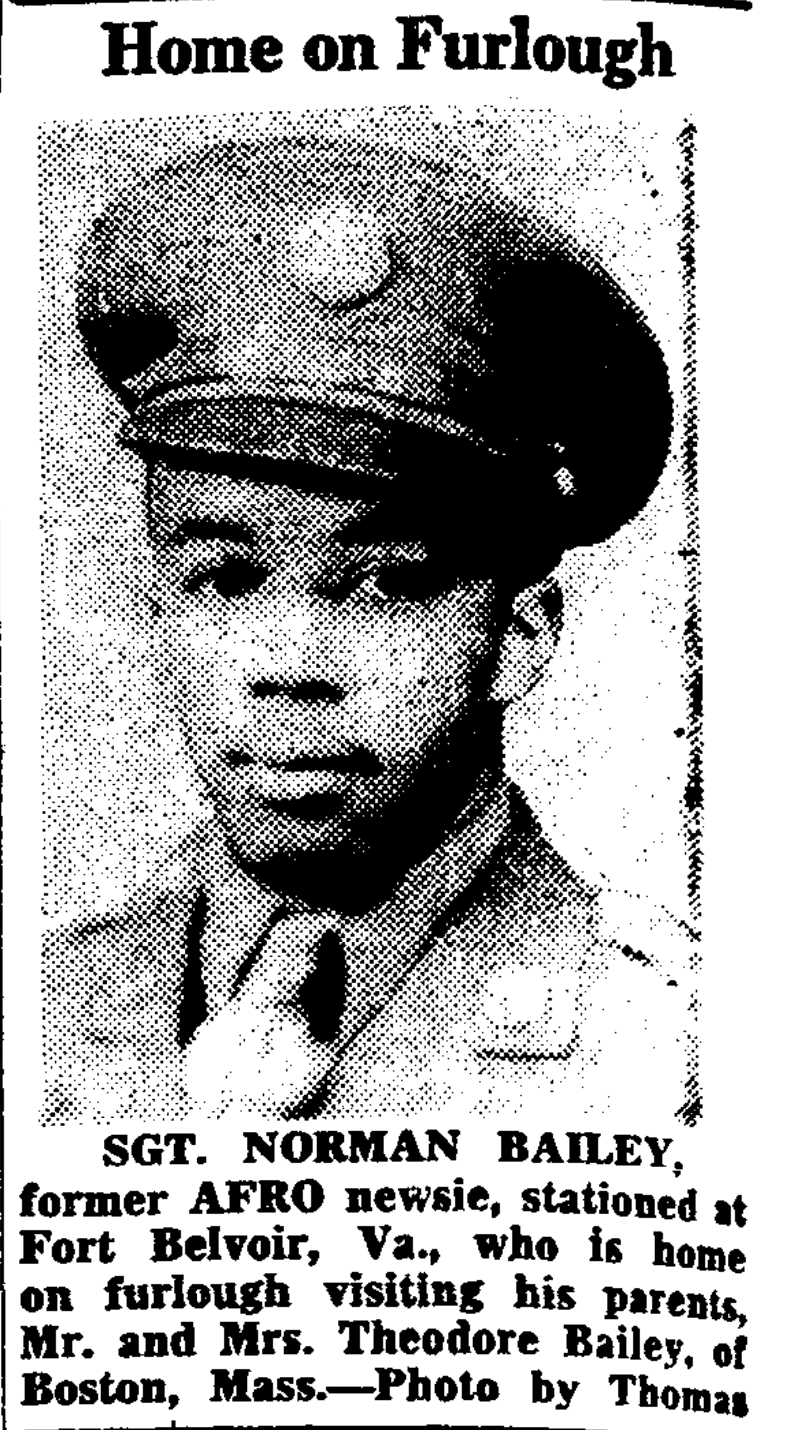

Image: “Revised Map of Norfolk and Vicinity, Compiled from Maps of Record, 1923,” map, 1923, Sargeant Memorial Collection, Norfolk Public Library (Va.), https://cdm15987.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15987coll7/id/36.

[3] “History of the Noank Shipyard,” Noank Shipyard Collection, Mystic Seaport Museum, accessed March, 2020, https://research.mysticseaport.org/coll/coll353/;

Theodore Lee Bailey World War I Draft Card, Norfolk, Virginia.

Image: Noank Shipyard, "Noon Revival Meeting," 1917, NHS1975.123, Noank Historical Society, http://02d243c.netsolhost.com/htdocs/vex3/6734B2FC-06C0-42F9-AD8D-337550160070.htm.

[4] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 243.; U. S. Census Bureau, Census Record, 1920, Boston Ward 7, Suffolk, Massachusetts.

Image: "Massachusetts Avenue, about 1926." Photograph. 1925. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/nv935g021.

[5] Theodore Bailey entry, Boston City Directory for 1923 (Boston, Massachusetts: Sampson and Murdock, Company Publishers, 1923), 167; Subsequent City Directories have the publisher Sampson and Murdock, Company Publishers: Boston City Directory for 1926, 776.; Boston City Directory for 1927, 776.; Boston City Directory for 1928, 775.; Boston City Directory for 1929, 777.; Boston City Directory for 1930, 778.; Boston City Directory for 1931, 781.; Boston City Directory for 1933, 357.; Boston City Directory for 1934, 327.; Boston City Directory for 1935, 328.; Boston City Directory for 1936, 651.; Boston City Directory for 1937, 652.; Theodore Bailey entry, Boston City Directory for 1939 (Boston, Massachusetts: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1939), 142.; Subsequent City Directories have the publisher R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers: Boston City Directory for 1941, 154.; Boston City Directory for 1942, 154.; Boston City Directory for 1943, 148.

Image: Abdalian, Leon H. "Dock Sq. to Adams Sq." Photograph. 1930. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/fj2375789.

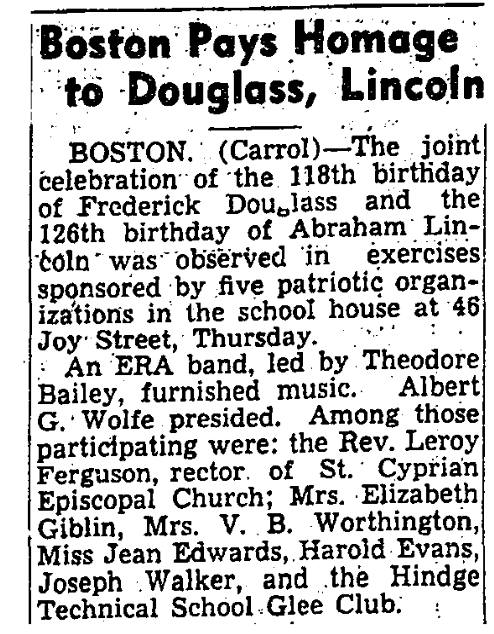

[6] "Boston Pays Homage to Douglass, Lincoln," Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Feb. 23, 1935, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 10.; John P. Deeben, “The Correspondence Files of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, 1933-1936,” Family Experience and New Deal Relief, Prologue Magazine 44, no.2 (2012), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/fall/fera.html.; “Philly Personals” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Dec 1, 1934, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 15.; “Symphonic Swing Band for W.P.A.: Other Groups Planned in Reorganization Here,” Daily Boston Globe (Boston, MA), Aug. 28, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, 8.; “The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) (1933),” The Living New Deal, accessed March, 2020, https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/federal-emergency-relief-act-fera-1933/.

Image: "Boston Pays Homage to Douglass, Lincoln," Afro-American (1893-1988) (Baltimore, MD), Feb. 23, 1935. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 10.

[7] C. Elliott Freeman, Jr., “Massachusetts State News: Boston,” The Chicago Defender (National edition) (Chicago, IL), Dec 12, 1936; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, 5.; Elliott Freeman, “Buzzing Around Bean Town: Boston,” The Chicago Defender (National edition) (Chicago, IL), Apr 17, 1937, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, 22.; Elliott Freeman, “Buzzing Around Bean Town: Boston,” The Chicago Defender (National edition) (Chicago, IL), May 22, 1937, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, 11.; “Federal Music Project (FMP) (1935),” The Living New Deal, accessed March, 2020, https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/federal-music-project-fmp-1935-1943/.; “Greater Boston, Society,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Apr 25, 1936; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 18.; "Negro Units of the WPA," The Boston Chronicle (Boston, MA), July 24, 1937, 1.; “New Deal Programs: Selected Library of Congress Resources,” Web Sources, Library of Congress, accessed March, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/newdeal/fmp.html.; “New England: Great Boston, Society,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Dec. 14, 1935; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 14. “New England: Great Boston, Society,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), May 2, 1936; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 18.; “Red Cross Hygiene Class, Graduation,” Daily Boston Globe (Boston, MA), Dec 5, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, 3.; “South End Carnival Features Checker Match with Human Beings as Pieces,” Daily Boston Globe (Boston, MA), Jul 31, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, 13.;

Image: Weitzman, Martin, Artist, and U.S Federal Music Project, W.P.A. Federal Music Project information given regarding locations of W.P.A. schools and all subjects taught. New York, (New york: federal art project, between 1936 and 1941) Photograph, https://www.loc.gov/item/98516767/.

[8] George Noble, “Military and Navy,” Daily Boston Globe (Boston, MA), Jul. 11, 1937, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, A42.

Image: “Bedford Veteran's Administration Hospital,” postcard, unknown, pre-1950s, Objectid P1993 121, Bedford Properties and Landmarks Collection,Bedford Historical Society, https://bedfordmahistory.pastperfectonline.com/photo/2C4B726E-0417-4FCC-956E-034453072990.

[9] “City News,” Guardian (Boston, MA), June 28, 1941, 8.; Theodore L. Bailey World War II Draft Card, The National Archives at St. Louis.

Image: “Building 105,” Charlestown Navy Yard, photograph, ca. 1943, Image ID = 9649-4, Boston National Historical Park Archival Collection.

[10] “AFRO Visitors,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), May 29, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 2.; “Boston Music Group Elects Officers,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Jul. 17, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 19.; “Founder John Henry Murphy Sr.,” Newspapers, The Afro-American, PBS, accessed March, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/afroamerican.html.; “Home on Furlough,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Jul. 24, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 16.; “The First Colored Professional, Clerical and Business Directory of Baltimore City 31th Annual Edition, 1943-1944,” Archives of Maryland Online, accessed March, 2020, http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000521/html/am521--13.html.; “The Whirling Hub,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), May 30, 1936, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 18.; “The Whirling Hub,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Aug. 7, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 17.; Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 36-37, 216.

Image: “Home on Furlough,” Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Jul. 24, 1943, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Afro-American, 16.

[11] Theodore Bailey entry, Boston City Directory for 1944 (Boston, Massachusetts: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1944), 142.; Subsequent City Directories have the publisher R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers: Boston City Directory for 1947, 101.; Boston City Directory for 1948-1949, 102.; Boston City Directory for 1952, 297.; Boston City Directory for 1954, 265.; Boston City Directory for 1956, 249.; Boston City Directory for 1957, 217.; Boston City Directory for 1958, 96.; Boston City Directory for 1959, 96.

Image: “Administration Building, Harrison Avenue,” photograph, 1940s, Record Identifier: 7020001-0067, Boston City Hospital Collection, Boston City Archives, https://cityofboston.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_e8e05620-754a-4c4c-b561-4753e002df28/.

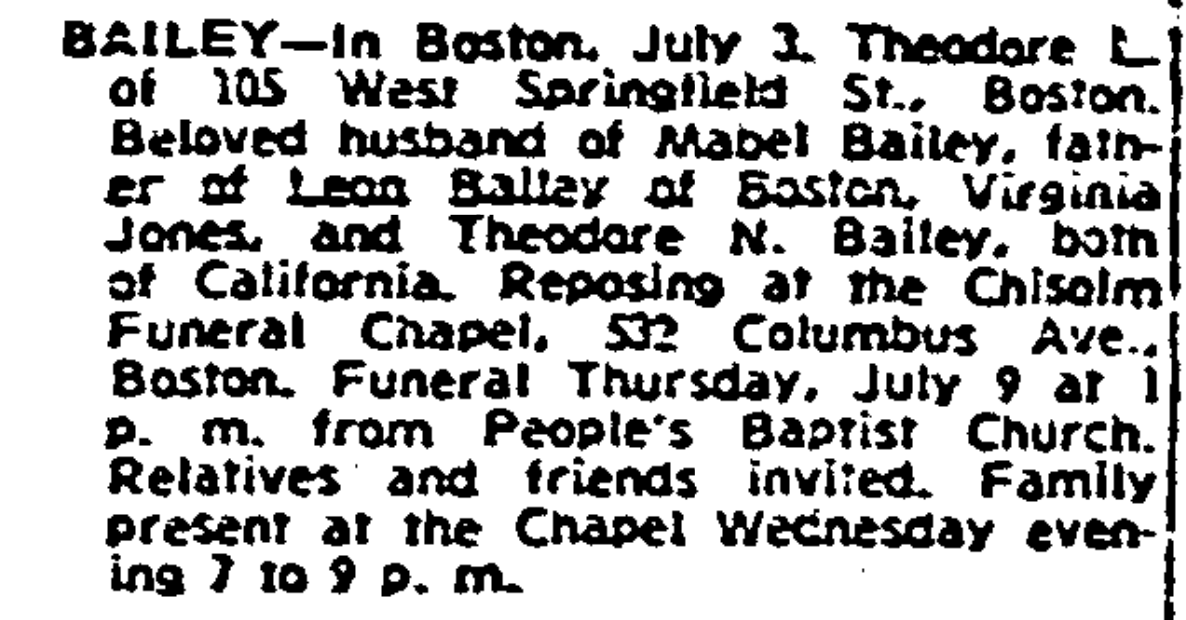

[12] “Death Notices,” Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), Jul. 3, 1959, 21, Genealogy Bank.; Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 264.

Image: “Death Notices,” Boston Traveler (Boston, MA), Jul. 3, 1959, 21, Genealogy Bank.