Last updated: March 30, 2023

Article

The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet into the Earth (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

For over 100 years, men ventured deep into mineshafts to reach the valuable copper deposits of Michigan's upper peninsula. The copper that passed through the Quincy Mining Company's candlelit No. 2 Shaft in the 19th century might have become a button on the uniform of a Civil War soldier, a wire for one of the first telephone poles, or part of the early electrical grid. Who produced this metal and how did they live? What was it like to work underground?

The workers who settled in the mining towns of “Copper Country,” the Keweenaw Peninsula on Lake Superior, came from a variety of different ethnic European backgrounds, including Italian, Finnish, Slavic, German, Irish, and Cornish. Mining companies attracted immigrants to this sparsely populated area with its company towns, where there were houses, hospitals, libraries, and schools ready to be filled. Conflicts over this paternalistic relationship and ethnic tensions reached a boiling point in 1913, when membership in the Western Federation of Miners union swelled. That year, the unionized miners went on a famous and deadly 8-month-long strike that changed mining and the very social fabric of Keweenaw forever.

The historic No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse stopped copper mining operations in 1945. Today, it is a Keweenaw heritage site and a resource within the Keweenaw Historical Park.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination files for the "Quincy Mining Company Historic District" (with photos) and the archives of Keweenaw National Historic Park and Michigan Technological University, Library of Congress, and Ted Holstrom’s private collection. The lesson was written by Ted Holmstrom, a teacher and resident of the former mining district, for Keweenaw National Historical Park in collaboration with the Copper Country Intermediate School District. It was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff in collaboration with Kathleen Harter, Chief of Interpretation & Education at Keweenaw National Historical Park. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson can be used in American history units on the Industrial Revolution and Immigration in the late 19th century and the early 20th century.

Time Period: Late 19th century and early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet into the Earth

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

-

Standard 1- How the rise of corporations, heavy industry, mechanized farming transformed the American people.

-

Standard 2- Massive immigration after 1870 and how new social patterns, conflicts, and ideas of national unity developed amid growing cultural diversity.

-

Standard 3- The rise of the American labor movement and how political issues reflected social and economic changes.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet into the Earth

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme 1: Culture

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

- Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns, cultural transmission of ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

- Standard B - The student describes the role that supply and demand, prices, incentives, and profits play in determining what is produced and distributed in a competitive market system.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationship to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants, and security.

Objectives for students

1) To explain the importance of copper mining to U.S. and Michigan history;

2) To compare and contrast the nationalities of various workers in the mining industry and to highlight patterns that placed certain groups of people in particular jobs;

3) To explain the role paternalism played in the mining community and debate its merits;

4) To describe the dangers of working at a mine;

5) To identify and describe another historic mining community in the United States.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

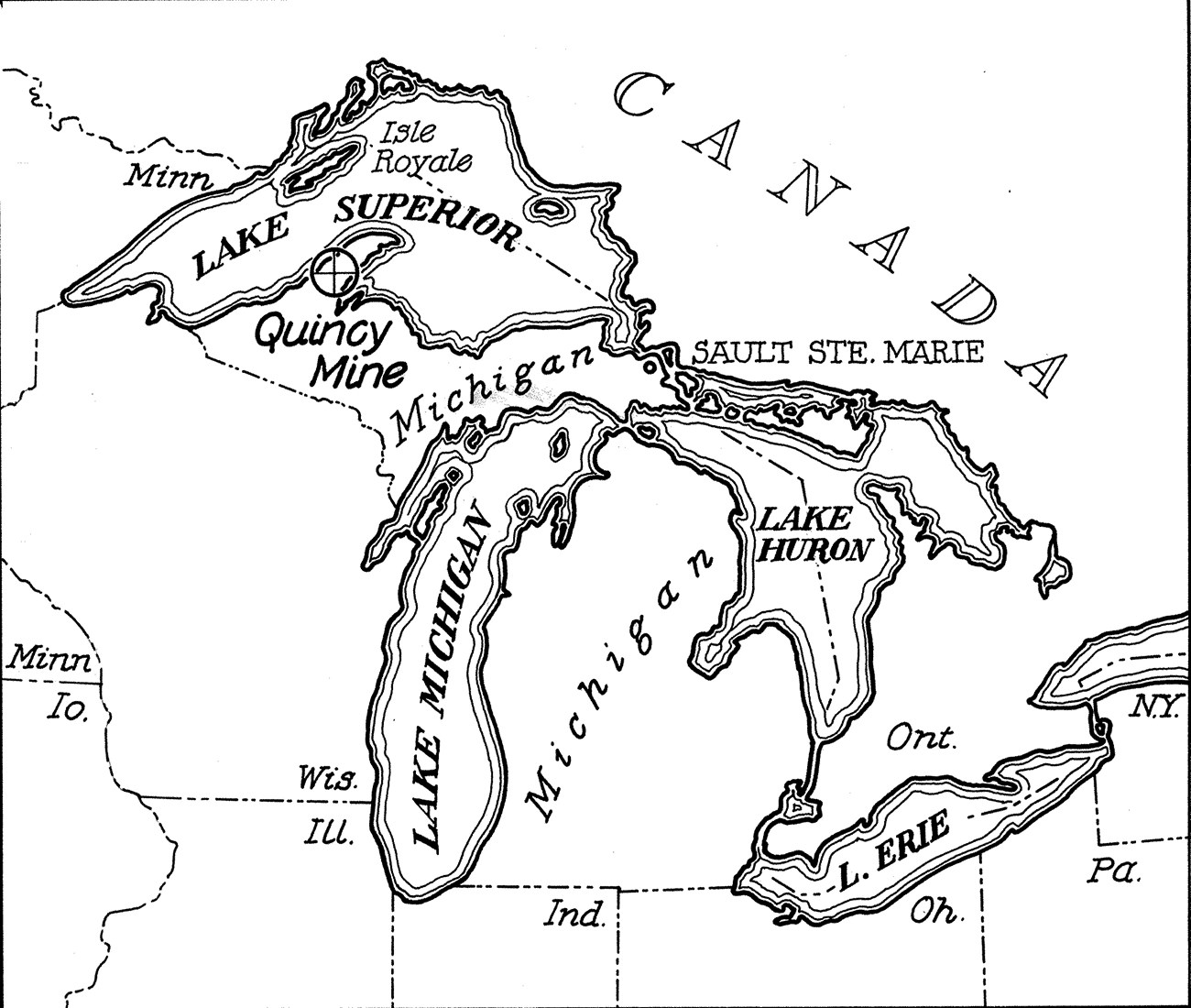

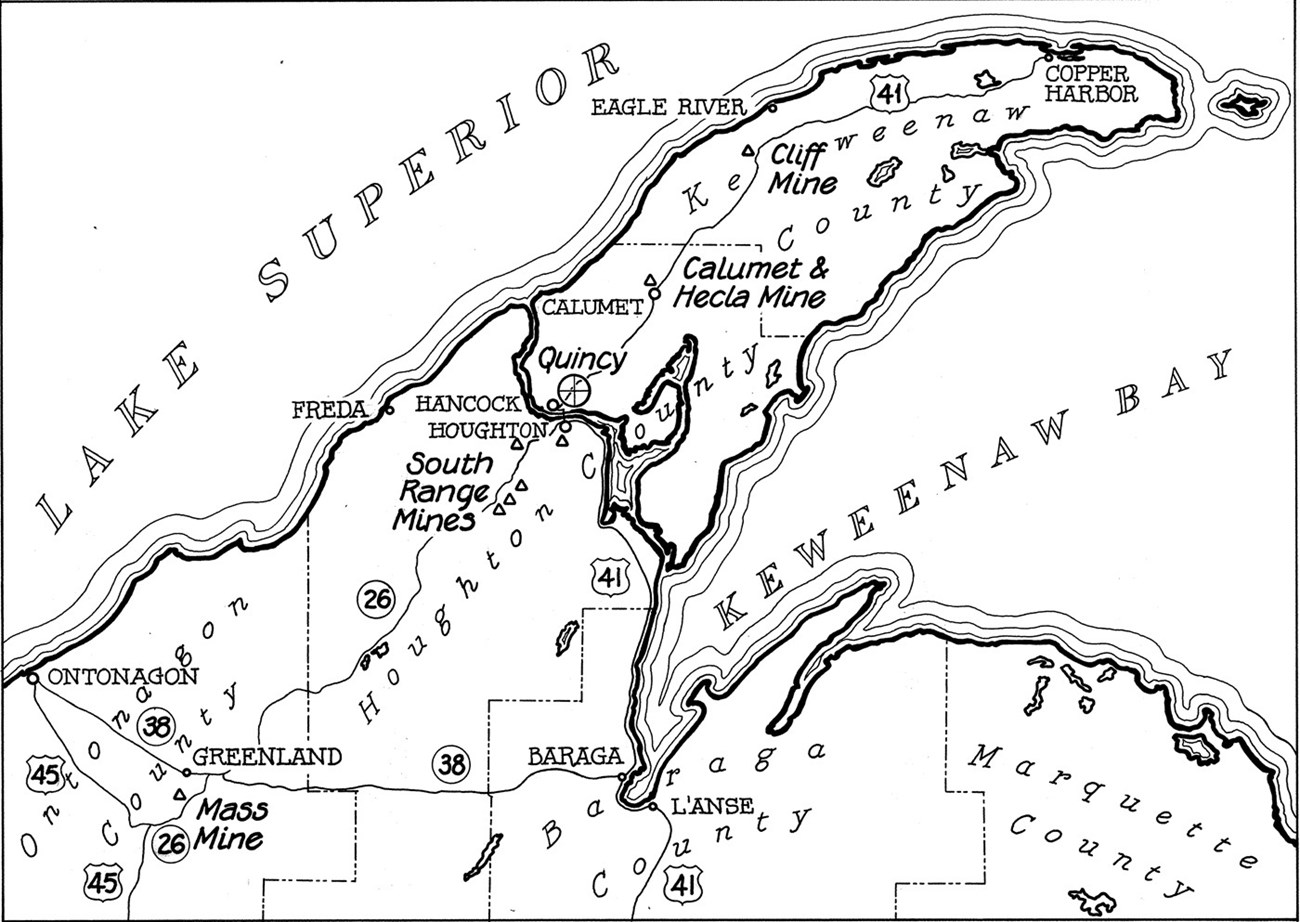

1) three maps of the Lake Superior Copper Region and the Quincy Mine Location;

2) four readings about the history of the Quincy Mining Company, the production of copper, the ethnic background of mine workers, and the conflict between employers and employees in the Copper Strike of 1913-14;

3) five photos: two of miners at work, one of the funeral parade for the Italian Hall Disaster, and two of Quincy Mining Company housing;

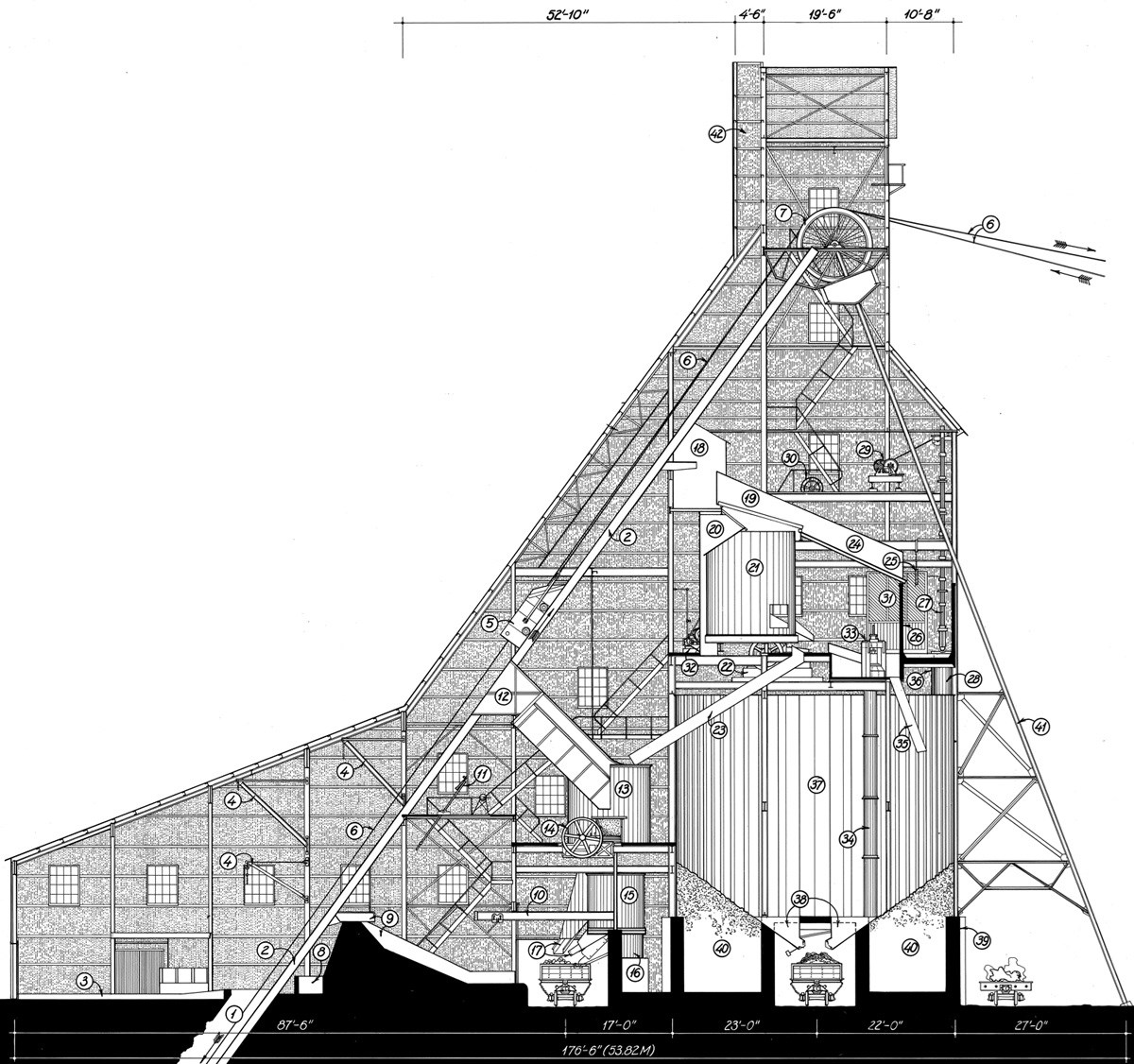

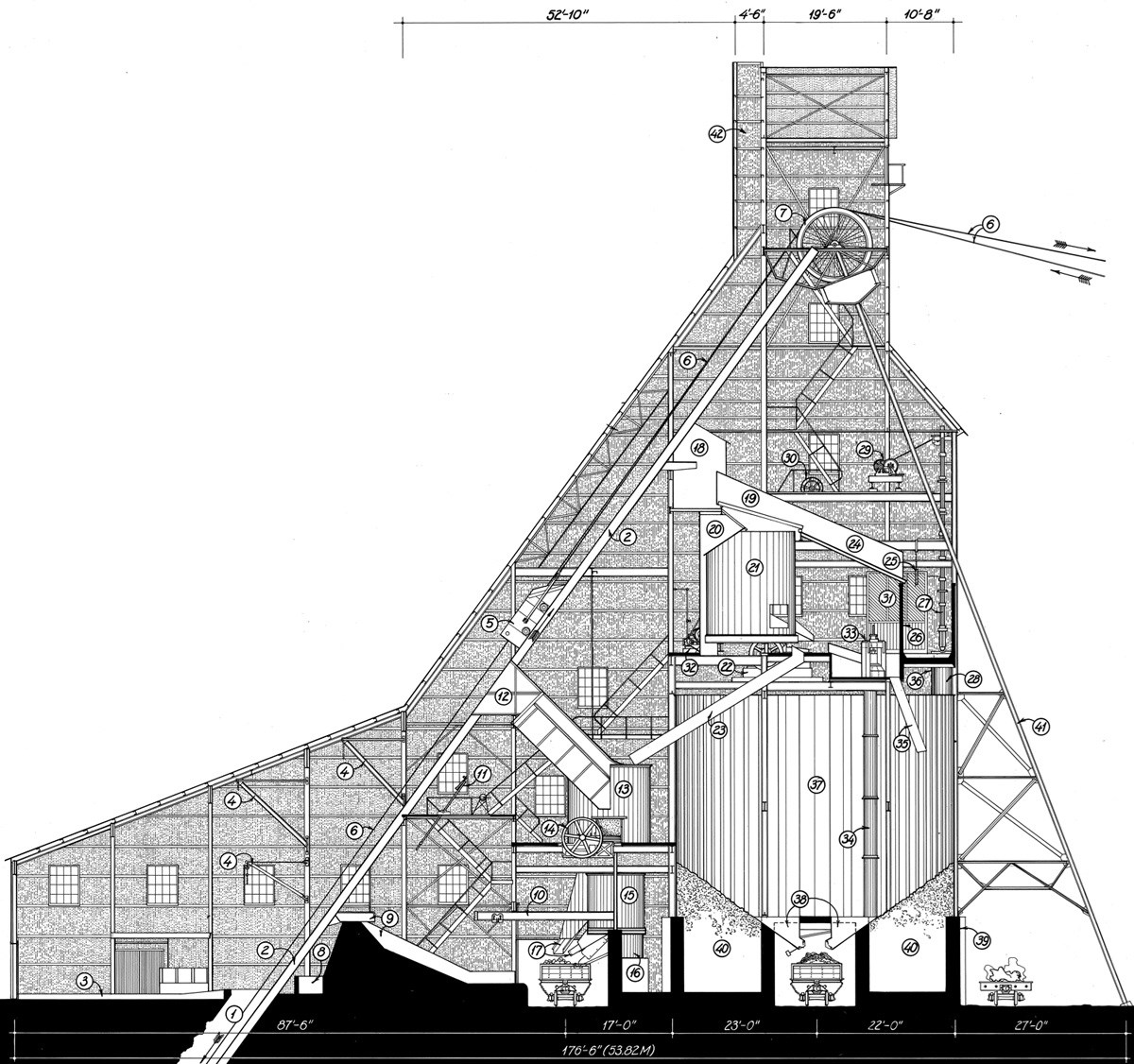

4) one illustration of the No. 2 Shaft-Rockhouse.

Visiting the site

The Quincy Mining Company Historic District is a resource within the Keweenaw National Historical Park. The historic site is operated by the Quincy Mine Hoist Association, a partner organization. The site is open to the public daily 9:30am-5:00pm in the summer and open for limited hours during spring/fall. For more visitor information, contact Keweenaw Heritage Sites by phone at 906-337-3168 or by email at info@KeweenawHeritageSites.org.

For more information via the National Park Service, call 906-483-3176; write to: Keweenaw National Historical Park, 25970 Red Jacket Road, Calumet, MI 49913; or visit the Keweenaw National Historical Park website.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What could be this building's purpose?

Setting the Stage

|

Humans have lived and mined copper in the Keweenaw Peninsula, on the shores of Lake Superior, for over 6,000 years. The earliest evidence of human copper mining in the region dates back to 7000 BCE. These miners extracted copper from the rock by heating it with fires and then throwing cold water on the heated metal. This caused the rock around the copper to crack, so the miners could access the copper from the broken rocks with hammers and wooden levers. Ancient Native American groups used Lake Superior copper to make weapons, tools, jewelry, and other items. The Ojibwa people who lived on the peninsula when the French and English colonized North America in the 17th and 18th centuries pulled decorative chunks from the lake or molded copper pieces into spoons and bracelets. 1 Thurner, Arthur W. Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

|

Questions for Map 1

1) Circle or point to identify the American states, countries, and bodies of water in Map 1. Where is Quincy Mine?

2) Use a map of the United States and identify what part of the country Map 1 shows. How far away is Quincy Mine from New York City? Use a ruler and the scale to measure distance.

3) What natural features can you find on Map 1? How do you think an immigrant in the 1870s might travel to Quincy Mine from Europe? How do you think Quincy Mine transported goods to the east and south?

(Library of Congress, HAER Record)

Questions for Map 2

1) What part of Michigan does Map 2 show? What bodies of water surround it? (Refer to Map 1 if necessary)

2) What do you think the people who lived here did for work? What jobs did they hold and what skills do you think they might have had?

3) How many mines are labeled on the map? What kind of metal do you think they produced? What do you think was the most likely way the mining companies transported what they produced? Why?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Superior Copper and the Quincy Mining Company

The small Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula was one of the best places to mine for copper in the United States during the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was profitable because the copper of this area occurs in a pure metallic state and because there was a lot of it. Keweenaw is a stretch of land fifty miles long and fifteen miles wide, that lies at the northernmost tip of Michigan as it juts out into Lake Superior. The area is known as “Copper Country.”1

Modern mining started in Keweenaw in the 19th century after explorers in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan discovered abandoned American Indian mining sites and investors reopened mines. These deposits were mined in the early 1840s and the mining companies removed all of the copper from these sites, but they created the industry and attracted settlers to northern Michigan.

The Quincy Mining Company formed in the Keweenaw Peninsula in 1846. The company built its own facilities for processing the copper from start to finish. It also built houses and community buildings for company employees and their families. It had a rough start, but the mine was successful and Quincy grew. Maps of the Quincy Mines that were made in 1892, 1902, and 1920 show more development of housing and transportation between the shafts and the various mill buildings owned by Quincy.

Quincy Mining struggled during its first ten years to make a profit. In 1856, the company was saved when a neighboring mine discovered a copper deposit on the Keweenaw Peninsula that was about 12 to 15 feet thick at the surface. This deposit ran through land Quincy owned and the company began to mine it. The Keweenaw mining industry grew and the region became known for its copper. Michigan produced more copper than any other state in the U.S. when the Civil War started in 1861. At that time, almost 90% of America’s copper came from Michigan and over half of Michigan’s copper came from the Quincy Mine.

During the Civil War, production of copper briefly fell but not enough to stop the mining business. People still needed copper. By 1862, the company produced 2.1 million pounds of refined copper. This level of production allowed the mining company to start paying back the investors who first supported the business. Mines like Quincy supplied the raw material that was shipped to factories and then used to make brass buttons, copper canteens (small containers that hold water), bronze cannons, and ship-building materials. Between 1862 and 1868, the Quincy Mine produced more copper than any other mining company in the country.

After the war, American factories demanded copper more than ever before. One reason for this was the invention of electricity-powered technology, like electric lamps and telephones. These inventions needed copper parts and electrical wires. Electrical wire mills switched from making iron wire to making a new kind of copper wire in 1877. This copper wire was strong enough to be strung overhead for new telephones and the older telegraph system. The copper industry boomed throughout the United States. On the Keweenaw Peninsula, about 400 mining companies operated between 1872 and 1920.1

People at Quincy Mine called the company “Old Reliable” because it was so successful. The company paid stockholders every year between 1868 and 1920. When the mine peaked in 1910, it had produced about 458,000,000 pounds of copper.2 Part of the success of the mine was the advancement in technology. Copper mining technology improved over the years since the mine opened in 1846. Mining at Quincy began with men using drills powered by hand and black powder (gunpowder). By the 20th century, a single man could operate a drill by using air pressure, explosives, electric locomotive hauling tools, and steam-powered tools. In 1930, the mines at Quincy were the deepest in the Western hemisphere. The deepest mining shafts -- measured on the incline, not surface to bottom vertically -- went over 9,000. The No. 2 Shaft was the deepest mine in the United States by 1931.

The price of copper began to fall in 1920 and the company’s profits fell, too. Quincy stopped producing copper in 1931 because of the Great Depression. During the Depression, industries all over the country slowed down. This meant that factories did not need to buy as much copper as they did before the economic crisis. The Quincy Mining Company reopened in 1937 when prices rose and Quincy stayed open to supply Allies with copper during World War II. Even though it reopened, its boom years were over. By 1943, Quincy opened a reclamation plant to process “stamp sand.” Stamp sand is gravel created when workers mill ore. It contains small pieces of copper. Because less copper could be mined from underground by this time, Quincy Mine workers began to turn this sand into copper ore. When the war ended, the mine had paid out $27 million back to its investors and produced 848,000,000 pounds of copper. Quincy stopped mining copper in 1945, but the reclamation plant continued to produce copper until 1967.

Questions for Reading 1

1) Why did people need copper in the late 1800s? What did Americans use it for?

2) When did copper production take off for the Quincy Mine Company?

3) What nickname did the Quincy Mine receive? Why was it called this?

4) List ways new technologies affected Quincy Mine. How do you think these new technologies might have affected the people who worked at Quincy Mine?

Reading 1 was adapted from “Quincy Mining Company,” Library of Congress, HAER (Historic American Engineering Record) collection for Quincy Mining Company, Hancock, Houghton County, MI; National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Quincy Mining Company Historic District, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988; National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Quincy Mining Company Stamp Mills Historic District, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2007; “Copper in the USA: Bright Future Glorious Past” Copper Development Association, Inc.

1 National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, “Quincy Mining Company Historic District”, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988.2 Lankton, Larry. Cradle to Grave: Life, Work, and Death at the Lake Superior Copper Mines. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Who worked at Quincy Mine?

Most of the people who worked for the Quincy Mining Company during the copper boom were immigrants or the children of immigrants. The first wave of immigrants arrived in Michigan to work in the mines in the 1840s. These immigrants were from Ireland, Cornwall (England), Germany, and Scandinavian countries like Norway and Sweden. Michigan’s French-Canadian immigrants worked as timbermen and woodchoppers, but rarely in the mines. Italians would come in larger groups at the end of the 19th century. Each ethnic community created its own churches, meeting halls, and welfare societies. In 1870, nearly all residents of Houghton County (where Quincy Mine is) were immigrants or children of an immigrant.

New waves of immigrants came to work in the mines in the early 1900s and copper mining continued to boom. By 1905, Quincy Mine employed about 1,400 people. A third of the new workers were from Finland. Other new immigrant groups included people from Italy and Austria. The experiences of Finns and Italians at Quincy were the same as earlier immigrants: they were hired for the most laborious and low-paying jobs. The connection between a worker’s ethnicity and job placement put some ethnic groups at an advantage. People in the established groups had higher-paying jobs and were the bosses, supervisors, and engineers. New groups had lower-paying jobs and worked less-desirable jobs. This divide sometimes caused tensions between immigrant groups.

Most of Quincy Mine’s immigrant workers took unskilled jobs. The hardest jobs were mucking and tramming. These unskilled jobs required workers to shovel rock and push heavy tram cars, a task easily fulfilled by someone with little mining experience. Early waves of Finnish immigrants often found themselves in this sort of work. Some of the unskilled immigrants from Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy were also trammers when they arrived.

Another hard job was processing rock when it came to the surface. After the workers brought the rock to the surface, they dumped it from the ore cars and then rock-house workers took over. The rock-house laborers sorted the ore and sent it out in rail cars to its next processing stop. As with the underground work of mucking and tramming, rock-house work was often considered unskilled. Immigrants from Finland, Italy, Croatia, and Slovenia often did this back-breaking work.

Not everyone who worked at a mine was called a "miner." At most mines, a “miner” was a skilled worker who operated a drill or drilling machine, filled holes with explosives, and set off explosive charges. Early Cornish immigrants often became miners because copper mining was an important industry in Cornwall, England. Men from Cornwall could enter Michigan’s mines with experience. Unlike the Cornish, the Irish and German immigrants did not take skilled jobs immediately. In later years, workers of other ethnicities could be promoted to the position of miner.

Mining captains, assistant captains, and shift bosses oversaw the copper production at Quincy Mine. The mining captain was the executive officer. Assistant captains and shift bosses helped the captain manage the underground work force. Assistant captains could be in charge of individual shaft or an underground working area. Shift bosses were responsible for individual groups of men and might be directly involved with actual underground work. Mining captains stood out from the workmen because they wore white clothing. At first, skilled mining captains were often the Cornish immigrants with experience mining in England. After a generation passed, college-trained mining engineers took over the work of the experience-trained mining captains.

"Local" immigrants were French-Canadian men who traveled from Canada to work at Quincy. They built timber support beams for the mine shafts. This was a skilled job. Timbermen were employed to move, cut, install, and maintain wooden beams underground. These beams lined the mine shafts and kept the mine from collapsing, but they could catch fire. The mines were candlelit. The mines used sprinklers to spray water and flame-fighting chemicals onto the beams to keep them from being set on fire.

A Keweenaw resident’s ethnicity was a very important part of his or her social identity when the copper industry boomed between 1870 and 1930. Journalists included information about a person’s ethnicity next to names in articles. They would call a person a “Finnish trammer” or a “Croatian laborer” and did not always give a full name. Ethnicity was used in jail records, too. Jail documents kept track of the ethnicity of jailmates rather than their place of birth. The mining companies kept written records of workers’ ethnicities, too. Quincy and other mining companies recorded workers’ ethnicities in their official employment records.

Questions for Reading 2

1) What were some of the main immigrant groups in copper mining communities? Who was known for mining in their homeland?

2) Who qualified as a “miner”? Who usually held this job? If you were not a miner, what type of job would you hold? Who typically held these jobs?

3) How large a role did ethnicity play in the daily life of workers? Where you can find examples of a person’s ethnicity being used to define their status?

4) Women and girls did not work in the mines, but they were part of the Quincy community. How do you think female immigrants might have been affected by their ethnicity in Keweenaw?

Reading 2 was adapted from National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Quincy Mining Company Historic District, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988; “An Interior Ellis Island: Ethnic Diversity and the people of Michigan’s Copper Country,” Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Producing Copper

The Quincy Mining Company was one of the largest copper-producing companies in the 19th century. Part of the success of the Quincy Mining Company was that it owned and operated every building necessary to process the copper from start to finish. Raw, copper-bearing rocks went through three steps before it was the pure copper that the Quincy Mining Company could sell. T

hese steps were mining, milling, and smelting. Mining was taking the rock with copper in it out of the earth. This was the first step. The second step was separating the copper from the rock. This is milling. The last step was smelting, which was melting pieces of copper mineral together to make concentrated metal. Quincy Mine employees did all three steps in the mine’s own facilities.

The first facility copper went through was a shaft-rockhouse. A shaft-rockhouse covered the underground shaft entrance and above-ground it was the rock-processing center. The shaft-rockhouse allowed rock to be processed as soon as it was brought up from below. Rock used to be processed in separate shaft-houses and rock-houses. It was sent up to the surface to the shaft-house and then moved to the rock-house for processing. This was not as efficient as a combined shaft-rockhouse. The shaft-rockhouse’s height allowed different materials to be dumped on different levels. This meant different tasks could take place in one building. At a shaft-rockhouse, three men could move about 1,000 tons of rock in 12 hours.1

Before workers could process the copper, they needed to dig it out of the ground. Shafts (mining tunnels) had to be created so miners could dig out the rock. These shafts were named in the order that they were created. Men who mined on the bottom level spent their entire 10-hour shift working more than a mile underground. After the workers dug out the rock, they put it in a bin and sent up the shaft’s lift into the shaft-rockhouse. Workers pulled the bins up to the surface by a hoist. After the bins passed through processing in the shaft-rockhouse, workers moved the copper-heavy rocks to a stamp mill. The bins traveled to the stamp mill on a surface tramway or railroad. At the stamp mill, the rocks were crushed (stamped) and washed. Stamping the rocks concentrated the copper mineral by separating it from the rock. The leftover pieces of rock were mixed with water, sent from the mill through a trough, and dumped in Portage Lake or Torch Lake.

Back at the stamp mill, the concentrated mineral, now 60 to 80 percent copper, was sent to the smelter. At the smelter, workers melted the mineral in a furnace. Larger pieces of mass copper also went into the furnaces. Furnacemen dipped ladles into the liquid, molten copper and poured it into molds to make copper ingots. When it cooled, these solid bars of copper were ready to be shipped across the lakes and sold.

Quincy Mine built its first shaft-rockhouse in 1892. By 1901, a combined shaft-rockhouse was at mine shafts No. 2, 6, 7, and 8.2 The historic No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse was built for Quincy's deepest mine. It extended over 9,000 feet at an angle and reached a total depth of 6,225 feet below the Earth’s surface. It was built in 1908 during some of Quincy’s most productive years. Production stopped at this Shaft-Rockhouse in 1945. It is one of the oldest intact buildings at the site.

Questions for Reading 3

1) What are the three steps for making copper ingots?

2) What is a shaft-rockhouse? Why was it important to the mining process?

3) What dangers do you think the Quincy employees faced during each step of copper production?

Reading 3 was adapted from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Quincy Mining Company Stamp Mills Historic District, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2007; “Quincy Mine’s Shaft-Rockhouse”Keweenaw National Historical Park, National Park Service; “An Interior Ellis Island: Ethnic Diversity and the people of Michigan’s Copper Country,” Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections.1 "No. 2 Shaft-Rockhouse, 1908.” Sheet 17 of 34. Library of Congress, HAER Record.

2 Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: Strike!

In the early twentieth century, Michigan’s Copper Country was in trouble. The mining companies faced new competition when copper mines opened in Montana and Utah. The price of copper dropped when more mines produced it and the mining companies looked for ways to save money. Many mine laborers worked long hours in dangerous conditions for under $3 a day and they were not happy that the mining companies would not raise wages for everyone. The companies wanted their income from selling copper to go toward profits, not wages. Some miners had lost their jobs to new technology that the companies brought in to make up for lost profits. Tensions also built between company managers and mine laborers because of the tie between ethnicity and employment opportunities. These conditions led to a strike.

In July 1913, many of the mine workers in the Keweenaw Peninsula went on strike. A strike is an event where employees refuse to work until the managers or owners agree to the workers’ demands. At Quincy and at other Copper Country mines, workers stopped going to the mines, smelters, and stamp mills. They refused to work until the companies improved working conditions. Pro-labor organizations in the United States knew about the strike and supported the strikers. A union sent the strikers a weekly stipend until the strike ended. The stipend supported the men and their families during the strike.

The Copper Country mine workers had several demands. They wanted an eight-hour work day and higher pay. They wanted the mining companies to stop using a new type of mining drill. This new drill was operated by one man, not two.1 This meant that people who used to work on the old drill either lost their job or worked fewer hours, since the new drill needed half the labor as the old drill. This also meant that the drill operator worked alone and no one was there to help him if he was injured. The strikers demanded that the mines bring back the old drill that two men operated. They also wanted union recognition

The strike was also an ethnic conflict, because ethnic groups were often paired with a type of job. Most of the workers who went on strike were part of the most recent wave of immigrants. Their ethnic backgrounds were Croatian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Finnish. Mine workers who were least likely to join the strike were from established ethnic groups, including Cornish, Scottish, German, and Scandinavian. Members of these groups were usually in a high-paying and highly skilled position, and therefore unlikely to go on strike. Croatian workers were in some of the lowest-paying and physically demanding mining positions, and nearly all laborers from Croatian backgrounds went on strike.

Another reason that the miners went on strike was the system of paternalism in the mining communities. The workers depended on the mining companies for more than a paycheck. The mining companies were involved in the mine workers’ lives in many ways. The mining companies provided their workers with houses as well as schools, fire departments, hospitals, and libraries. Workers benefitted, but this meant their communities were controlled by their employers. In 1913, the workers rebelled against paternalism when they went on strike and worked with a union. Jack Foley, a former mill owner, said this about the paternal system:

“Alright, [the mining companies] built the houses for them, they had to have houses, that was a necessity. Bringing people over here from the European countries to work in the mines. They had to have housing. Where are they going to live, outside in the parks? There were no parks--sleeping under a tree--they had to have housing…They had stores around the mines, some of these miners never saw their paycheck. It went right to the store--they bought their clothes, their fuel, from the mining companies. They bought their groceries from the mining company’s store…They had their hospitals. They were serfs--feudalism--that’s feudalism. And that is not good labor relations."2

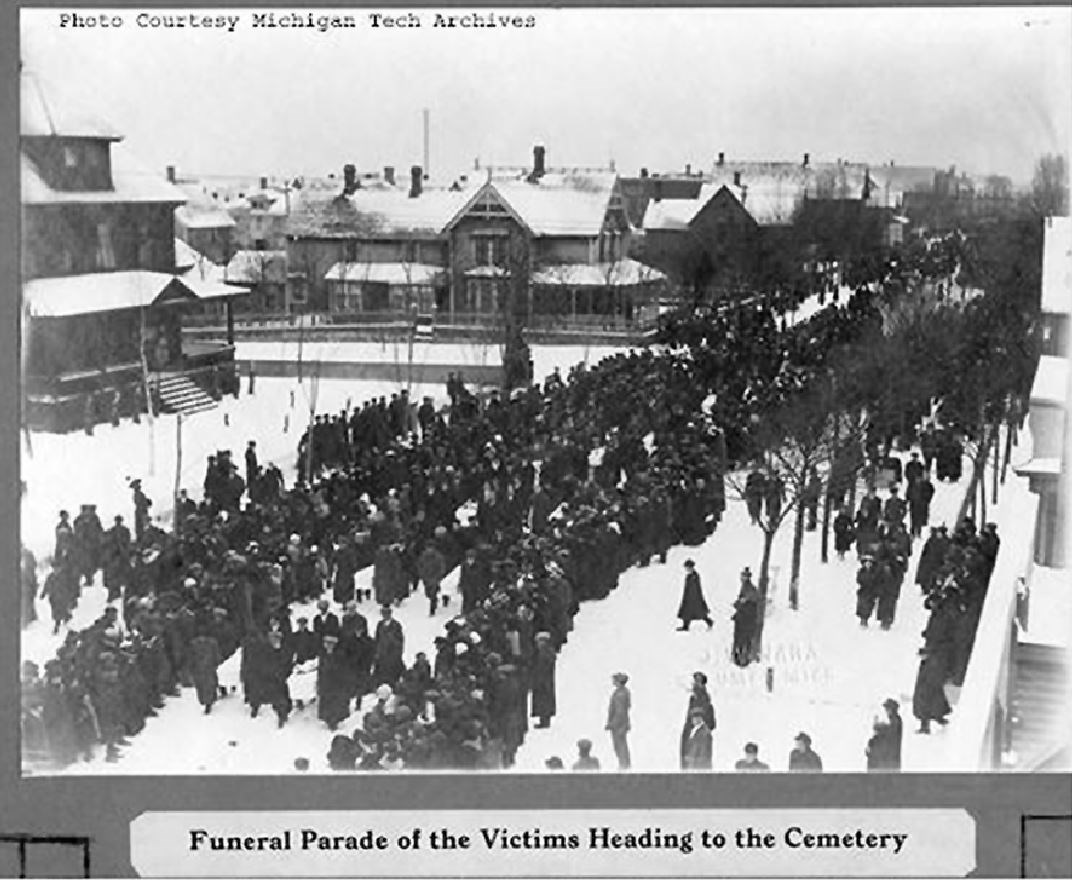

The strike lasted for eight months. The mining companies hired private security guards and the Michigan National Guard went to Keweenaw to keep order. Fights broke out between the supporters of the mine companies and supporters of the strikers. Hundreds of people were arrested. The deadliest night of the strike was Christmas Eve. On December 24, 1913, the Italian Hall in Calumet hosted a Christmas party for strikers and their families. During the party, someone yelled “fire.” There was no fire, but the people in Italian Hall tried to escape. Seventy-three people, including fifty-nine children, died when everyone panicked and tried to get out of the building at the same time. Some people thought that the person who yelled “fire” was sent by one of the mining companies to cause trouble, but he or she was never identified.

The strike ended in April 1914 when the strikers voted to go back to work. The strike was considered a failure. The mining companies did not bring back the two-man drill. Some mines in Copper Country gave their employees an eight-hour workday, but not all. The strikers did not get the raise they wanted. About 2,500 men and their families left the Keweenaw Peninsula after the strike. Some moved to Detroit to work in new car factories. The strikers who stayed had trouble finding jobs, because the companies did not want to hire someone who was part of the strike. Mining, milling, and smelting continued at Quincy Mine, but the community was changed.

Questions for Reading 4

1) What were some of the issues workers had with their employers? What were the three demands of the strikers?

2) What is “paternalism”? How was it practiced at Quincy?

3) How does Jack Foley describe labor relations between mine employers and employees? Do you agree with him? Why or why not?

4) How much of a presence do you think employers should have over its workers’ lives? Was mine ownership of houses, stores, and other community buildings intruding too much into the lives of Quincy employees? Explain your answers.

Reading 4 was adapted from “An Interior Ellis Island: Ethnic Diversity and the people of Michigan’s Copper Country,” Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections, Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula By Arthur W. Thurner, and Cradle to Grave: Life, Work, and Death at the Lake Superior Copper Mines by By Larry Lankto; and includes excerpts from an interview with Jack Foley by Art Puotinen on August 9, 1972 as part of the Finnish Folklore and Social Change in the Great Lakes Mining Region Oral History Project 1972-197.

1 Lankton, Larry. Cradle to Grave: Life, Work, and Death at the Lake Superior Copper Mines. Oxford University Press, 1993. P 225.

2 Jack Foley to Art Puotinen. Interview. August 9, 1972. Dollar Bay, Michigan.

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse.

Questions for Illustration 1

1) What is this building’s purpose? Where is the copper in the illustration?

2) Why is this building shaped the way it is? How does its shape serve its purpose?

3) What do you think it was like to work in this building in the early 1900s?

Visual Evidence

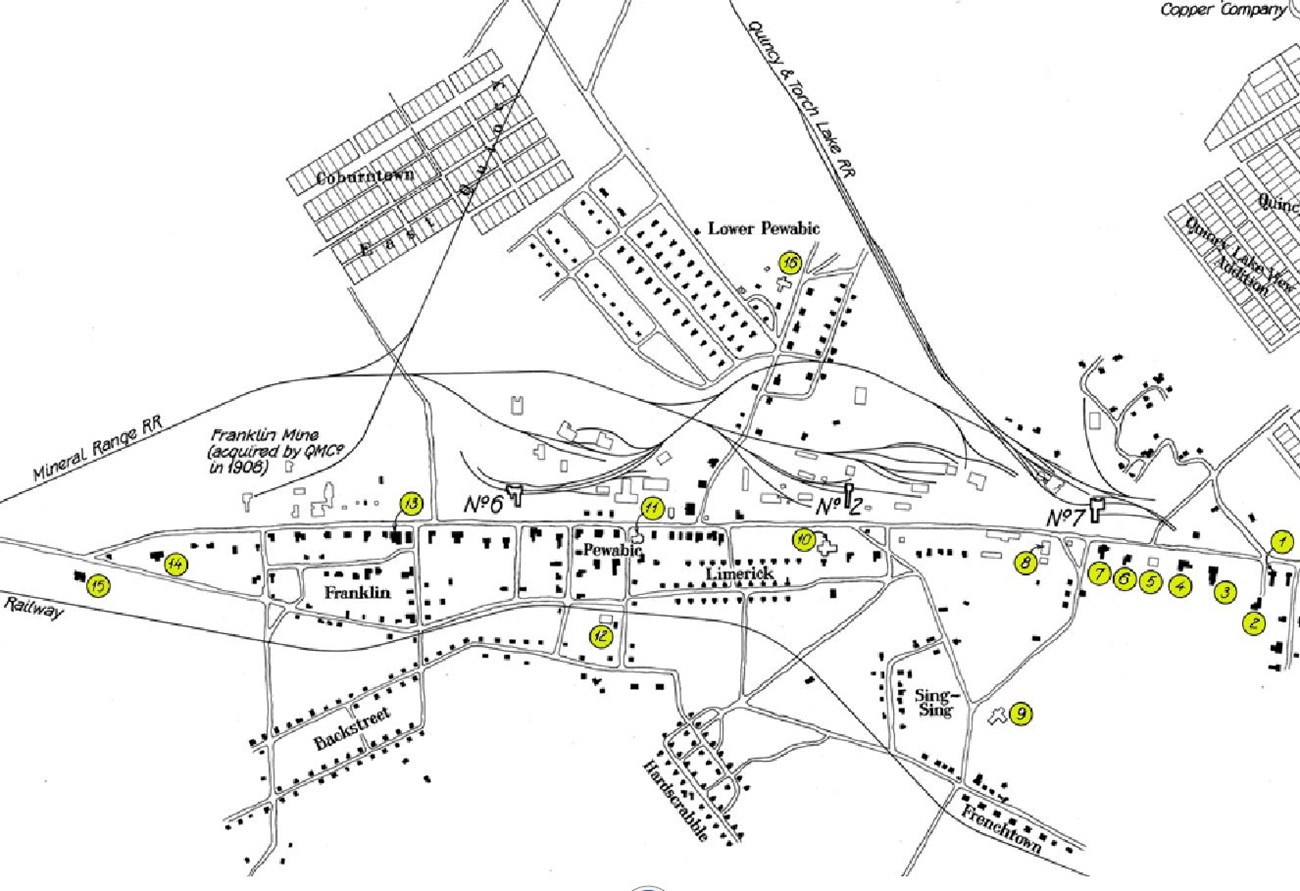

Map 3: Quincy Mine Location, c. 1920.

(Library of Congress)

Key for map of the Quincy Mining Company community

|

1. Doctor’s Residence |

11. Methodist Church |

Questions for Map 3

1) What evidence do you see of a paternalistic mining community in Map 4? (Refer to Reading 4 if necessary)

2) Quincy employees lived in the neighborhoods of Limerick, Singsing, Frenchtown, Hardscrabble, Pewabic, Franklin, and Backstreet. Underline the names of these places. Find the mine shafts and circle them. What would be some of the benefits of living that close to work? What might be the drawbacks?

3) Find the No. 2 Shaft. What community buildings are nearby? Why do you think these places were built near the mine shaft? What do you think that reveals about the Quincy community?

Visual Evidence

Map 3: Quincy Mine Location, c. 1920.

(Library of Congress)

Key for map of the Quincy Mining Company community

|

1. Doctor’s Residence |

11. Methodist Church |

Questions for Map 3

1) What evidence do you see of a paternalistic mining community in Map 4? (Refer to Reading 4 if necessary)

2) Quincy employees lived in the neighborhoods of Limerick, Singsing, Frenchtown, Hardscrabble, Pewabic, Franklin, and Backstreet. Underline the names of these places. Find the mine shafts and circle them. What would be some of the benefits of living that close to work? What might be the drawbacks?

3) Find the No. 2 Shaft. What community buildings are nearby? Why do you think these places were built near the mine shaft? What do you think that reveals about the Quincy community?

Visual Evidence

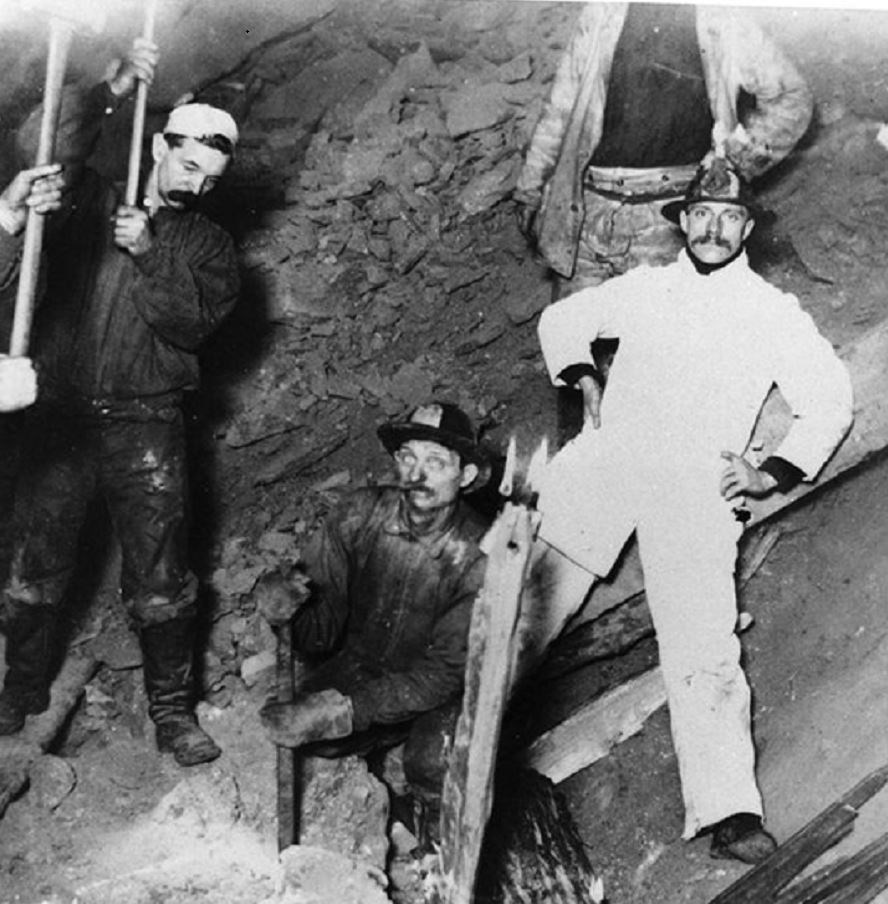

Photo 1: A Quincy mine, 1890.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Who are these men? What are they doing?

2) Why is one man wearing white? What do you think his background is? What about the men in dark clothing? What might be their origin? (Refer to reading 2 if necessary)

3) Where is the light coming from in this photo? What do you think it was like to work under these conditions?

Visual Evidence

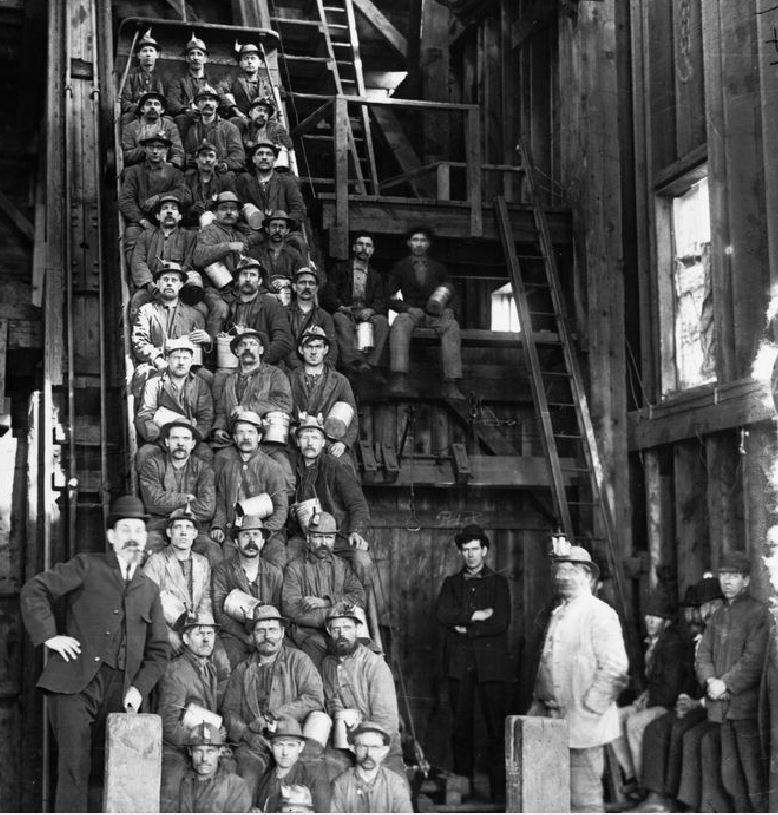

Photo 2: Miners Ready to Descend in a Quincy Man Car, c. 1900.

Questions for Photo 2:

1) Where do you think this photo was taken? Who are the men seated? Where do you think they are about to go?

2) Describe how the workers are seated. Do they look comfortable? Based on their seating arrangement, how do you think the shaft is shaped?

3) Who do you think the men not sitting in the car might be? What different kinds of jobs can you think of that happened above ground at a copper mine?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Funeral Parade for Victims of the 1913 Italian Hall Disaster.

Questions for Photo 3

1) What do you think this photo tells us about the Keweenaw mining community?

2) Do you think all of these people are from the same ethnic groups or different groups? Why or why not? Who do you think came to this funeral? (Refer to Reading 4 if necessary)

3) How do you think this funeral affected the strikers and the 1913 strike?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Quincy Stamp Mill Worker Housing.

Photo 5: Quincy Mining Company Agent's House.

Questions for Photo 4 and Photo 5:

1) Describe houses and landscape in Photo 4. Describe the house and landscape in Photo 5. What details stand out?

2) How is the home of a stamp mill worker different from a company agent's house? What features are different? How are they different?

3) Based on what you have read, what ethnic groups do you think would have been most likely to live in which neighborhood? Why?

4) Photo 4 is a historic image of the Quincy Mining Company Stamp Mills Historic District, but many of the houses pictured were destroyed to make space for new buildings. Why would someone want to preserve the historic buildings that remain? What do the old buildings in your town tell you about your community's history?

Putting It All Together

The following activities encourage students to think creatively or critically about what they learned in No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet Into the Earth, either to look closer at Quincy or to study another historic mining community in the United States.

Activity 1: What’s in a Name?

Many immigrants came to work at the No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse. Have students research the possible countries of origin and immigration patterns from those countries to the U.S. in the 19th Century. Divide students into small groups with a list of 4 names that includes both miners and mining captains. Have each group take the list of people who lived around the No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse and research the origin of each name. Use this website to find the possible nationalities for each name: www.ellisisland.org.

Here are the names of mining captains from Quincy: Rule, Piper, Williams, O’Neil, Pelto, Jenkins, Kopp, Coombs, Maunders, Jacobs, Whittle, Kendall.

Here are the names of workers from Quincy: Merilainen, Malinen, Wales, Mikkala, Uusitalo, Harmonen, Jacobson, Laitamaa, Turo, Kauppinen, Pelto, Storvis, Salminen, Paaka, Cliff, Hawkin, Latala, Gustavson, Ruotinnen, Reimi, Gustavon, Borlace, Pascoe, Wiivo, Goudge, Massini, Pioponen, Koski, Giusti, Forst, Fleming, Monticello, Ricci, Gimigneni, Kujala, Nikula, Kamula, Levonen, Kemppainen, Kotila, Minehan, Yalkanen, Kemppainen, Crowley, Commings, Saari, Leppaluta, Mattson, Hasett, Moilanen, Kotila, Sullivan, Moilanen, Ruski, Finley, Pelto, Mahon, Brown, Lynch, Pantera, Sefanic, Nikula, Komula, Levanen, Kotila, Kangas, Larson, Koski, Busch, Lencioni, Elonen, Salani, Marko, Priami, Andretti, Bartino, Antonnen, Johnson, Becia, Stefanic, Johnson, Nivala, Marta, Biagi, Hale, McMahn.

Have each group use what they learned in the lesson to discuss what the national origins of the names might say about the workers' backgrounds, possible reasons for people with those last names to immigrate to the United States in the 19th century, and his and his family's life in Keweenaw. Have each group create a poster outlining the results of their research and prepare for a presentation. Each group will present its findings to the class.

Afterward, facilitate a class discussion about immigration and labor. Ask students where in the world immigrants to the U.S. come from today. What challenges do they face? What kinds of work do they do?

Activity 2: Worker Safety at the No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse

Mine safety was always an issue between management and labor. Have your students practice writing creative dialogue based on what they learned in the lesson. Break students into pairs and assign each pair a phrase from this primary source document: “Quincy Mining Co., Rules and Regulations for the Protection of Employees,” “Killer Phrases Which Chloroform Ideas and Put Men’s Minds to Sleep,” and “Some of the Key Points of Supervisor-Worker Communications.”

Have each pair use their assigned phrase and the primary source document about communication to write a conversation between a fictional miner and a manager at Quincy. The setting, conflict, and outcome are up to the students, but they should start by thinking of a problem that might arise at a Keweenaw Peninsula mine and then have the characters work out how to solve it in a short conversation. At one point in the dialogue, the miner or the manager must say the phrase assigned to the students. The conversation should include references to places, issues, events, and groups of people students came across in the lesson. Have the student pairs perform their dialogues in front of the class and submit their conversations to you in written form afterward.

Activity 3: Mining in the U.S.A.

Have each student conduct an independent investigation into a historic mining operation in another part of the United States. Students can look at another copper mining region or study places where people extracted coal, oil, or precious metals. This list from the Bureau of Land Management is helpful for identifying possible sites. For a local history investigation, students can identify a historic mining operation in their state or near their own community.

Decide whether you want students to organize their findings as an oral presentation or a research paper. The presentation or paper should answer these questions:

-

Where was the mine? What did the mine produce? What was it used for?

-

Who worked in the mines? Where were they from? Was the mining community paternalistic, like the one at Quincy? If it was not paternalistic, what might be the reason?

-

How did people mine the resource from the Earth? Was the work dangerous?

-

How did the national economy affect the mining operation? How did the mining operation affect the local economy?

-

What happened to the mining community when the mine closed? Why did it close? Did another industry move in and replace it?

-

What did the community do when the mine closed? Did they stay or move away? If a lot of people moved away, where did they move to and what industry did they work in afterward? What jobs did they take if they stayed?

-

What kinds of buildings were at the mine? What happened to them when the mine closed? Were they abandoned, torn down, or used for another purpose?

If you chose to have students give an oral presentation, they can present to the class, parents, or a local group interested in mining history.

A digital alternative to the traditional oral presentation or research paper could be for students to take their research and use a free, online blogging site create a class website about historic mining. If they choose to make a class website about a local mining operation, consider asking your local library and historical society to link to your students' site from their own websites.

Activity 4: The Company’s or the Community’s Town?

The controversial system of paternalism and the company towns it created were common in America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like in the Keweenaw Peninsula, other industries that formed where there was little or no human community would create one to support workers. Have students explore the reasons for and against this system to prepare for a class debate. Break the class up into two teams. One team will take the side of industry barons who support the Company Town model and the other team will take the side of pro-labor organizations.

Each team will research real company towns across the United States to prepare for the debate. Each group should create a list of arguments for and against the paternalism system, and prepare an opening statement for their main argument. Tell the teams to think about how the other side will defend when they’re preparing. After the debate, the groups will turn in the list of arguments and a list of the sources they used for their research.

The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet into the Earth --

Supplementary Resources

By studying The No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse: 9,240 Feet into the Earth, students learn about the important connection between immigration and industrial labor in the 19th and 20th centuries and the significance copper mining to U.S. industrial history. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Keweenaw National Historical Park

This National Park Service website shares the history of all those who mined Keweenaw copper. It provides information about Park and partner resources, including a list of Keweenaw mining heritage sites like the No. 2 Quincy Shaft-Rockhouse.

Coppertown USA

Calumet, Michigan, in the Keweenaw Peninsula is "Coppertown USA." This website contains historical information in its online exhibits, with photos, as well as travel information for people interested in visiting the historical places in the peninsula.

Quincy Mine Hoist Association

The Quincy Mine Hoist Association, Inc., is the non-profit that offers tours of the historic mining town, information about copper mining in Michigan, and a giftshop at the site of the historic Quincy Mining Company. The organization also preserves the site of the Quincy Mining Company and cares for the historic No. 2 Shaft-Rockhouse. The organization's website includes information about the Quincy Mining Company.

Mining Engineering--History

The Michigan Technological University's Department of Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences website offers a page of resources on mining and mining history in Michigan. This includes a list of links to other websites about Michigan mine history. The MTU website also hosts a subsite with information about historic Michigan mine shafts.

Mining History Association

The Mining History Association website is a resource for anyone interested in mining history. The site's resources page includes a list of historic mines in the United States, organized by state, and links to research collections.